© -Steven Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“He was a mysterious man, as elusive and evanescent as his art. He could be maddeningly absent-minded; yet he could be closely attentive and solicitous, and you never quite knew how much Gil Evans was noticing about you. His childhood is an enigma, and there is even a question about his real name. Tall, lank, professional of mien, he was kind, self-critical, and self-doubting.”- Gene Lees

“The mind reels at the intricacy of his orchestral and developmental techniques. His scores are so careful, so formally well-constructed, so mindful of tradition, that you feel the originals should be preserved under glass in a Florentine museum.”

- Bill Mathieu [arranger-composer]

“His name is famously an anagram of Svengali and Gil spent much of his career shaping the sounds and musical philosophies of younger musicians. … His peerless voicings are instantly recognizable.”

- Richard Cook

“I bought every one of Louis Armstrong’s records from 1927-1936. … In every one of these three minute records, there’s a magic moment somewhere. Every one of them. I really learned how to handle a song from him. I learned how to love music from him. Because he loved music and he did everything with love and care. So he’s my main influence I think.”

- Gil Evans

In his book, Arranging the Score: Portraits of the Great Arranger, Gene Lees entitles his chapter on arranger-composer Gil Evans – He Fell from a Star.

As far as I was concerned, Gil could have come from anywhere.

I had no idea who he was until he magically appeared in my life one day courtesy of Pacific Jazz’s LP: - New Bottle Old Wine: The Great Jazz Composers Interpreted by Gil Evans and His Orchestra.

The album is a showcase for alto saxophonist Julian “Cannonball” Adderley who offers superb renditions of Gil’s arrangements beginning with St. Louis Blues and concluding with Charlie Parker’s Bird Feathers.

In essence, the eight treatments of Jazz classics on the album represent a salute to the first 25-years or so of Jazz composition and Gil weaves them together into a continuous “suite” through his use of transitional interludes, riffs and vamps.

The Gil Evans and His Orchestra part of the LP title is a bit of a misnomer because as Doug Ramsey explains, Gil “… never had his own full time band. For three decades he did his magical work with specially chosen musicians in studios and concert halls or with his once-a-week band at New York nightclubs. The evidence of his genius with shimmering vertical harmonies, moving lines, and mysterious voicings is in a body of recordings … .” [p. 415 from Doug’s essay Big Bands and Jazz Composing and Arranging After World War II, in Bill Kirchner, ed., The Oxford Companion to Jazz.

I no sooner had the chance to “digest” my initial “discovery” of Gil when suddenly he appeared to be everywhere present on the Jazz scene, mostly in the form of a series of block-buster Columbia LP’s that featured the trumpet playing of Miles Davis including Miles Ahead, Porgy and Bess and Sketches of Spain.

Who was this guy, where did he comes from and why was he “… regarded by many as the most gifted of all Jazz arrangers, but Ellington …?” [Ramsey. Loc cit.].

From a variety of sources, I eventually found out that Gil’s relationship with Miles antedated their Columbia albums by a dozen or so years going back their initial meeting at the 52nd Street clubs that came into existence primarily following World War II.

According to Ted Gioia:

“Evans was little known at the time, even in Jazz circles. His biggest claim to fame, to the extent he enjoyed any, was due to his forward-looking arranging for the Claude Thornhill orchestra.

The Thornhill band was a jumble of contradictions: it was sweet and hot by turns; progressive and nostalgic—both to an extreme; overtly commercial, yet also aspiring to transform jazz into art music. Like Paul Whiteman, Thornhill may have only obscured his place in Jazz history by straddling so many different styles.

Jazz historians, not knowing what to do with this range of sounds, prefer to relegate Thornhill to a footnote and dismiss him as a popularizer or some sort of Claude Debussy of jazz. True, this band was best known for its shimmering, impressionistic sound, exemplified in Thornhill's theme "Snowfall."

But this was only one facet of the Thornhill band. Evans, in particular, brought a harder, bop-oriented edge to the group, contributing solid arrangements of modern jazz pieces such as "Anthropology,""Donna Lee," and "Yardbird Suite." In due course, these songs would become jazz standards, practice-room fodder for legions of musicians, but at the time Evans was one of the few arrangers interested in translating them into a big band format.

Yet Evans was equally skillful in developing the more contemplative side of the Thornhill band. His later work with Davis would draw on many devices—static harmonies, unusual instruments (for jazz) such as French horn and tuba, rich voicings — refined during his time with Thornhill.

Gerry Mulligan would also contribute arrangements to the Thornhill band, and later credited the leader with "having taught me the greatest lesson in dynamics, the art of under-blowing." He described the Thornhill sound as one of "controlled violence"—perhaps an apt characterization of the cool movement as a whole [The History of Jazz, p. 281, paragraphing modified].”

Gil Evans offered more background about his time on the Thornhill band, with Miles on 52nd Street and the Boplicity or Birth of the Cool recordings in the following excerpts taken from his September 1956 interview on Ben Sidran’s NPR program Talking Jazz:

Gil: Yeah, right, I met Claude Thornhill in Hollywood. I came out there to write some arrangements for this band, Skinny Ennis's band, who was on the Bob Hope show. And I was writing arrangements for that.

Claude had an insurance policy that he was going to cash in, and he couldn't decide whether to go to Tahiti for the rest of his life or go back to New York and start a band. Which he decided to do. So I said to him, "If you ever need an arranger, let me know." So when his chief arranger got drafted, he sent for me. That was in 1941, '42. Then we all got drafted. So when he reorganized back in '46, I was with him again for a while.

But by that time, the scene had changed. The swing band era was over right? He just missed it by that three or four years in the service. He could have scored, but coming back into it again, pop music had come along and rock and roll, and folk and all that. So he had a hard time booking the band. And the band was big.

It was a wonderful workshop for me.

It had three trumpets and two trombones and two French horns and two altos, two tenors, baritone and a separate flute section, right? Three flute players, didn't play anything but flutes. And a tuba. So it was a big nut for him, and he finally had to give it up.

Ben: Was it Claude's idea to include the French horns and the tuba, initially?

Gil: The French horns were his idea, yeah. But the tuba, I got that in there. And the flutes. But the French horns he had quite a while. He had them before the war, too, you know.

He was like a practical joker, in a way. And so a clarinet was out in front of the band playing "Summertime"... I don't know if you ever heard of a clarinet player named Fazola?

Ben: Sure, Irving Fazola.

Gil: Beautiful tone, and oh, no one ever had a more beautiful tone than Fazola. So he's out there playing "Summertime," and Claude signaled to these two guys, and they came up from the audience and sat down and started playing these French horns in sustained harmony underneath him. And nobody in the band knew that was going to happen. Faz couldn't believe it. He looked around.

But the band sounded like horns anyway, even before he got them. It was one of the first bands that played without a vibrato, you know. Because the vibrato had been "in" all the time in jazz, ever since, well, Louis Armstrong, you know, that vibrato.

But then Claude’s band played with no vibrato, and that’s what made it compatible with bebop. Because the bebop players were playing with no vibrato. And they were interested in the impressionistic harmony, you know, that I had used with Claude. Minor ninths and all that.

That's how we got together, really. That's the reason we got together. Because of the fact that there was no vibrato plus the harmonic development. Because up until that time, with the swing bands, mostly the harmony had been from Fletcher Henderson, really. Where you harmonize everything with the major sixth chords and passing tones with a diminished chord, you know. So that was how things changed with bebop.

Ben: Also, the addition of the French horns and the tuba got the arrangements out of the more traditional "sections"—brass section, woodwind section—and made it more of a continuous palette for you.

Gil: Well, when Miles and I got together to do the Capitol record [Birth of the Cool] we just had to figure out how few instruments, and which ones, we could use to cover the harmonic needs of Claude Thornhill's band, you know. Naturally, with a big band like that, you have a lot of doubles. But we just trimmed it down to the six horns. Six horns and three rhythm, and those six horns covered all the harmonic needs that we had. …

Ben: That particular recording very quietly started some sort of revolution in jazz.

Gil: I wasn't even there. You know, I had to go home to see my mother in California, so I wrote that arrangement and gave it to Miles. But we were all so in tune with each other that I didn't have any worries at all. They just played it, and when I heard it, it was as though I had been there.

That's the way it was with all the records I made with Miles, the big band records, too. Because even though the notes were different, and they weren't familiar with the arrangements, they were so familiar with the idiom, you know, that we made those big band records in three three-hour sessions with no rehearsal. Nowadays, that's unheard of, right? You get a hundred hours, now, or more. But we got nine hours to make that thing, with no rehearsals. But the band, the whole band I picked out, they had the idiom under their fingers. So it was possible to do that.

Ben: That band, the "Boplicity" band, came together through a series of informal gatherings at your apartment over a couple of years.

Gil: I rented a room a couple of blocks from 52nd Street, you know. When I got off the train, I got in a cab and I went right to 52nd Street. I didn't have a place to stay. I threw my bag in a check room and I just walked up and down The Street there and met a bunch of my heroes. First night, I met all my heroes! I met Ben [Webster] and Lester [Young], Erroll Garner and Bud Powell, all these people the first night.

So I got a room a couple blocks away, a basement room. Just one big room with a bed and a piano and a record player and a sink. And I left the door open for two years. Just left it open. I never locked it. When I went out, I never locked it. So sometimes I'd come home and I'd meet strangers. And most of the time I met people like Miles and John Lewis and people like that. George Russell.

We talked a lot about harmony. How to get a "sound" out of harmony. Because the harmony has a lot to do with what the music is going to "sound" like. The instruments have their wave form and all that, but the harmony means that you're putting together a group of instruments, and they're going to get their own independent wave form, right? You can't get it any other way except as an ensemble together.

So Miles and I talked about that lots of times. And played chords on the piano. And that's how it happened.

Ben: The "sound" that you did come up with so perfectly suited Miles' sound that it almost seemed like one gesture.

Gil: That's right...

Ben: You talk about the extension of the Thornhill sound. You once said about the Thornhill band that "the band was a reduction to inactivity, a stillness..."

Gil: Oh, it was. That's right.

Ben: And "the sound would hang like a cloud."

Gil: That's right. Oh yeah.

Ben: Part of what you created, then, in the "Boplicity" session is a new approach to jazz, where even with a small group, it wasn't a separate thing, a rhythm section and a horn section, but rather it was a "sound." Almost a studio form before there were studio forms.

Gil: Yeah, right.

Ben: You mention the Miles Ahead big band session. "Boplicity" was recorded in 1949 ...

Gil: We didn't get together again until '57...” [pp. 16-19]

We found this summation by Bill Kirchner on the significance of these Boplicity or Birth of the Cool recordings in Gene Lees’ chapter on Gil:

“Saxophonist/composer/arranger/author Bill Kirchner, who teaches jazz composition at the New School, wrote in a paper delivered at a conference on Miles Davis held on 8 April 1995, at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, that the group that grew out of those sessions in Gil's pad was an anomaly: "It recorded only a dozen pieces for Capitol and played in public for a total of two weeks in a nightclub, but its recordings and their influence have been compared to the Louis Armstrong Hot Fives and Sevens, and to other classics by Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Charlie Parker. Though its personnel changed frequently, many of the nonet's members and composer-arrangers became jazz musicians of major stature. Most notable were Davis, trombonists J. J. Johnson and Kai Winding, alto saxophonist Lee Konitz, baritone saxophonist and arranger Gerry Mulligan, pianist and arranger John Lewis, pianist Al Haig, drummers Max Roach, Kenny Clarke, and Art Blakey, and arrangers Gil Evans and John Carisi...

"The Birth of the Cool sides were recorded in three sessions on 21 January and 22 April 1949, and on 9 March 1950. Issued initially as single 78s and eventually in various LP collections, these recordings had an enormous impact on musicians and the jazz public. Principally, they have been credited - or blamed, depending on one's point of view - for the subsequent popularity of "cool" or "west coast" jazz. Indeed, composer-arrangers such as Mulligan, Shorty Rogers, Marty Paich, and Duane Tatro were inspired by the Birth of the Cool instrumentation and approach.

"A good deal of their music, though, was more aggressive and rhythmic than some critics would lead us to believe - the frequent presence of such impeccably swinging drummers as Shelly Manne and Mel Lewis alone insured that.

"But the Birth of the Cool influence extended far beyond west coast jazz, and frequently appeared in all sorts of unexpected places. In the '50s, east coast composer-arrangers such as Gigi Gryce, Quincy Jones, and Benny Golson produced recordings using this approach, as did traditionalist Dick Gary, who used the style in orchestrating a set of Dixieland warhorses. Thelonious Monk, with arranger Hall Overton, used an almost identical Birth of the Cool instrumentation for his famed 1959 Town Hall concert. The format was proving to have all sorts of possibilities for creative jazz writing.

"Gil Evans spent much of the rest of his career expanding on the innovations of his Thornhill and Birth of the Cool scores."

What is generally overlooked is a point made by Max Harrison: that the "cool" did not begin with those nonet sessions. "There has always been cool jazz,"…” [pp. 91-92]

Perhaps because my initial involvement with Jazz was in California in the 1950s when the music of the West Coast “cool” school was still very much apparent, I have always had an affinity for its sound or texture.

What I noticed almost immediately about Gil’s writing was it’s appealing texture.

But what is a musical definition of texture which joins with melody, harmony and rhythm [meter] as a fourth building block used to create a musical composition?

Ironically, of these four basic musical atoms, the most indefinable yet the one we first notice is – texture.

Texture is the word that is used to refer to the actual sound of the music. This encompasses the instruments with which it is played; its tonal colors; its dynamics; its sparseness or its complexity.

Texture involves anything to do with the sound experience and it is the word that is used to describe the overall impression that a piece of music creates in our emotional imagination.

Often our first and most lasting impression of a composition is usually based on that work’s texture, even though we are not aware of it. Generally, we receive strong musical impressions from the physical sound of any music and these then determine our emotional reaction to the work.

Beyond the texture or sound of his music and the lasting physical and emotional impact it can create, Gil’s music is also heavily rhythmic – the most visceral and fundamental of all the musical elements.

Music takes place in time and like many great composers, Gil uses rhythms and the relationships between rhythms to express many moods and musical thoughts.

He uses rhythm to provide a primal, instinctive kind of foundation for the other musical thoughts [themes and motifs] to build upon.

This combination of powerful, repetitive rhythmic phrases and the manner in which he textures the sound of his music over them provides many of Gil’s arrangements with a magisterial quality.

Another of Gil’s great skills as a composer is that he never seems to be at a loss for the new rhythms that he needs to create musical interest in his work. He is a master at using the creative tension between unchanging meter and constantly changing rhythms and these rhythmic variations help to produce a vitality in his music.

In his use of melody, Gil’s approach to composing, arranging and orchestrating appears to have much in common with the Classical composers of the late 18th and early 19th century [Mozart & Beethoven as examples] in that he relies on a series of measured and balanced musical phrases as the mainstay of much of his work.

And like these Classical composers, Gil is also careful not to let one musical element overwhelm the others: balance between elements is as important as balance within any one of them.

Gil obviously places a high value on melody in his writing as his original themes or the manner in which he orchestrates the theme of standard tunes have a way of finding themselves into one’s subconscious and staying there a la – “I can’t get this tune out of my head.”

This is in large part because Gil works with melodies to make them easily-remembered short phrases, generally four or eight bars in length and these are often heard in combination with other similar phrases to fashion something akin to a musical mosaic with individual pieces joining together to create a musical whole.

Gil crafts little melodic devices that are wonderful examples of the composer’s art. And he has learned over the years to base his compositions out of the fewest possible melodic building blocks because if there too many melodies, or for that matter, too many rhythms and too many different chords in a piece, the listener can get confused and eventually bored.

And on the subject of chords, the building blocks of harmony, here Gil’s approach involving multi-part harmony is more akin to modern composers such as Debussy, Bartok and Stravinsky than to those of the Classical period.

As Bill Kirchner, Gene Lees and Max Harrison, among others, have noted, the melodic, harmonic, rhythmic and textural elements that are combined to make a “cooler” Jazz have been around since the beginnings of the music itself.

In the December 1958 and February 1960 issues of the original Jazz Monthly magazine, Max Harrison provided a comprehensive and analytical review of Gil Evans’ music and his career dating back to his time with the Claude Thornhill orchestra in the mid-1940s and the Birth of the Cool recordings through the issuance of the Miles Davis collaborations on Columbia and the earliest recordings under Gil’s own name on Pacific Jazz, Verve and Impulse.

These articles were later collected and published in book form under the title A Jazz Retrospect.

We will post Max’s essay from this book in its entirely to form the second part of our visit with Gil Evans, a musician whose “… lack of formal training may be the key to his originality, for he can arrange harmonies that no one else has ever arranged and cluster instrumental groups that no one has ever sectioned before.” [Jack Chambers, Milestones, Vol. 1, p. 95].

![]()

“He is perhaps the only great writer in Jazz history who has always tended to work as an arranger of the work of others and rarely as a composer of his own material.”

- Leonard Feather

Evans’s originality does not require original compositions for its demonstration. His arrangements of other people’s compositions simply sparkle with his individualism; they overflow with invention. …

His tastes have been unencumbered by convention or bias, and his career has been almost untouched by self-promotion or self-aggrandizement.

And he has managed, on his own terms and at his own pace, to produce a body of work that holds its own proud place in Jazz.”

- Jack Chambers

“He knows what can be done, what the possibilities are.”

- Miles Davis

For someone who was virtually unknown to the general public for most of his career, Gil Evans certainly didn’t escape the attention of Max Harrison as the following, exhaustive retrospective of Evans’ music will attest.

In his essay, Max explores in greater detail the concept of Gil’s arranging skills serving as a basis for re-composition.

The editorial staff at JazzProfiles is proud to share Max Harrison’s narrative with it’s readers as it is a model of thoughtful analysis about one of Jazz’s largely unrecognized Giants.

© -Max Harrison/Jazz Monthly Magazine, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“There has always been cool jazz. Far from being a new development of the 19505, this vein of expression, wherein the improviser 'distances' himself from the musical material, goes back almost to the beginning. The clarinetists Leon Roppolo of the New Orleans Rhythm Kings and Johnny O'Donnell of the Georgians, two bands that recorded in 1922, both avoided the conventions of 'hot' playing, as did other prominent jazzmen of that decade like Bix Beiderbecke and his associate Frankie Trumbauer. Much recorded by the New York school of the late 19205 follows a similar approach to expression, and this is true of several prominent figures of the 19308 such as Benny Carter, Teddy Wilson, and particularly Lester Young, whose links with the official 'cool' movement are acknowledged. The free jazz of the 19605, also, had its 'cool' exponents like John Tchicai and John Carter.

The comparatively reticent expression of such players was at a disadvantage in the early years, when jazz was heard mainly in noisy dancehalls and cabarets, and attempts at an orchestral extension of their work suffered for a related reason. The large bands of Fletcher Henderson, Jimmy Lunceford and many others spent most of their days touring, and this imposed various kinds of standardization, not least upon instrumentation: a leader playing one-night stands, perhaps with long distances to travel between them, could scarcely appear with a different personnel, repertoire and instrumentation at each. Despite their undoubted—if somewhat overrated—contribution to jazz, the swing bands, once established, stood in the way of further orchestral developments. These could only resume when the bands came off the road and orchestral jazz was created by ad hoc groups assembled mainly, if not exclusively, for recording purposes. Such conditions allowed far more varied instrumentation than hitherto, a wider choice of repertoire—which no longer had to be orientated to a dancing public, and the application of more diverse techniques of writing. Missing from much of this later music is that feeling of integration which can only be achieved when a group of men play the same repertoire together over a long period, but in compensation the studio players' superior executive skills allowed more adventurous scores to be attempted.

As usual when such changes occur, the shift of emphasis had begun earlier than is generally assumed, and in an unexpected place. At first, Claude Thornhill's band had sounded rather like that of Glenn Miller (!), but he showed it was possible, with fairly discreet additions to a conventional dance band instrumentation, like French horn and tuba, and with devices such as having the reed section play without vibrato, to produce a strikingly fresh sound. This change, however, was not merely for the sake of novelty, which would be of little musical interest, but was a step towards expressing modes of feeling different from, perhaps even opposed to, those of the swing bands. Snowfall, a rather static composition of Thornhill's, confirms this, but, although he always insisted it was the leader who created this sound, it was Gil Evans who knew what to do with it. As Evans said, the sound "hung like a cloud" (Quoted in Nat Hentoff, ‘Birth of the Cool,’ Down Beat, May 2nd and 16th, 1957), which implies extreme relaxation; upon this background he imposed movement, and part of the exceptional effect of the best Thornhill recordings arises from an ambiguity between the energy of the music's gesture and the passivity of its basic tonal quality.

This is perhaps most evident in The old castle (This is incorrectly labeled The troubadour on all issues), originally a fairly simple keyboard piece by Mussorgsky, which in Evans's hands tells of a world rich and strange, full of subtle, elusive feelings; indeed, Steve Lacy, who played a later vintage of Evans's music, said "Sometimes, when things jelled, I felt true moments of ecstasy, and recently a friend of mine who worked with the Thornhill band in the 19408 when Gil was principal writer said that some nights the sound of the band around him moved him to tears" (Jazz review, September, 1959). It is remarkable that this was done with what fundamentally was still a dance band instrumentation, yet Evans's work, like many seemingly radical departures, had a sound traditional basis, and he took certain cues from Duke Ellington, whose Koko he appositely quotes in Thornhill's Arab dance. As Andre’ Hodeir said (Andre’ Hodier, Toward Jazz, New York, 1962), as far as scoring for a conventionally-instrumentated swing band was concerned, Ellington was so far ahead of his contemporaries that for many years there was no question of the underlying principles of his writing influencing them. When Evans began orchestrating along basically similar lines (though always with greater and more varied flexibility) it was not surprising, therefore, that the fact went unrecognized.

In his finest Thornhill scores, Evans, instead of blankly contrasting the brass and reed sections like Henderson in his arrangements for Benny Goodman in the 19305, blends them in an almost infinite variety of ways. With such pieces as his evocative treatment of La paloma we find the craft of dance band arranging transformed virtually into an art of re-composition, for Evans quite drastically re-orders the components of each piece. In some cases, such as the extremely original writing behind and after the expressionless singing on Sorta kinda, the result almost seems a deliberate mockery of swing band conventions, so considerably does it improve on the standardized scoring which then prevailed in most other places.

That standardization reached such a point that we normally listen to swing records—and Henderson's band is a good example—only for the improvised solos, not for the ensemble scoring. But the orchestral idiom Evans worked out with Thornhill is of such distinction that the opposite is the case, and although the ensemble writing on, say, the performances of Charlie Parker themes is amazingly inventive and quite unlike anything else being done in the 19405, the soloists, with the exceptions of the guitarist Barry Galbraith on Anthropology and Donna Lee and the trumpeter Red Rodney in Yardbird suite, contribute nothing that is relevant. The best 'improvising' on these pieces, and on Robbins nest (despite an allusion to Kreisler's Caprice Viennois), occurs in Evans's orchestral passages, where he comments on the themes more creatively than any of the bandsmen, playing con' the ensemble just as a composer would. These sections are, indeed, a remarkable anticipation of George Russell's later assertions that “A Jazz writer is an improviser, too" (Sleeve note of George Russell, Jazz Workshop, American RCA LPM2534), and that the finest jazz composition "might even sound more intuitive than a purely improvised solo" (6). The point is underlined by comparing Evans's account of Yardbird suite with the bland arrangement of this piece Gerry Mulligan wrote for Gene Krupa, but Evans's best Thornhill moments come with the long Donna Lee introduction and the still more remarkable coda, which condenses some of the introductory material with real daring. Russell also said that a jazz composer might "write an idea that will sound so improvised it might influence improvisers to play something they have never played before" (George Russell: ‘Where Do We Go From Here? In The Jazz World by Dom Cerulli, New York, 1960). This is exactly what happened, though not inside the Thornhill band with its generally inadequate soloists.

Inevitably, many jazz musicians became interested in what Evans was doing, and prominent among them was Miles Davis, then a member of Parker's Quintet. Except in a few slow pieces like Embraceable you or Don't blame me, where he managed quite satisfactory improvisations, this trumpeter found the hectic complexity and furious aggression of bop uncongenial, and it is not surprising he was attracted to that music's opposite in the jazz of the late 19405. Eventually he decided, in Evans's words, that "he wanted to play his idiom with that kind of sound" (Hentoff, Ibid.), and the result was a band which, if it fulfilled scarcely any public engagements, made three historic recording sessions for the Capitol label in 1949 and '50. The story of that band and those sessions has been told many times and need not be repeated here, although it is useful to have Evans's confirmation that "the idea of Miles's band ... came from Claude's band in the sound sense. Miles liked some of what Gerry [Mulligan] and I had written" (Hentoff, Ibid.). In the course of discussions between Davis, Evans, Mulligan, John Lewis and others it was decided that what they needed was a medium-sized group that besides having the cool, restrained Thornhill sound would combine chamber music intimacy with much of the variety of texture possible to a full jazz orchestra. The instrumentation was: trumpet, trombone, French horn, tuba, alto and baritone saxophones, piano, bass, percussion, and, again according to Evans, this choice was decided by its being "the smallest number of instruments that could get the sound and still express all the harmonies Thornhill used" (Hentoff, Ibid). Although subject to various changes, the personnel was selected with care so as to ensure all participants were sympathetic to the musical aims of this unusual enterprise. That the leaders were not completely clear about those objectives, however, was shown by the fact that they considered giving their alto chair to the highly unsuitable Sonny Stitt (This little-known detail is given in Leonard Feather, Jazz – an Exciting Story of Jazz Today, Los Angeles, 1959), a Parker disciple, instead of to the far more apt Lee Konitz, who did in fact get it. The final choices were, indeed, excellent, and the music had a unity which must always be rare in jazz.

Nearly all the studio performances will repay detailed study, and they were supplemented years later by the appearance on an obscure Italian label (Miles Davis, Pre-Birth of the Cool, Italian Cicala BLJ8003; the relevant scores are, of course, by Gil Evans, not Bill Evans, as given on the sleeve) of recordings of 1948 broadcasts from the Royal Roost, where the band played briefly in New York; luckily, these include items not done for Capitol, such as Lewis's S'ilvousplait, Evans's Why do I love you?, alternative versions of his Moondreams, etc. The group's musical approach has been subject to repeated analysis because it represented the first viable alternative to bop, although, still following the Thornhill precedent, its importance lay in an ensemble style, not solo playing. Several of the pieces—Move, Venus de Milo, Budo—were mainly vehicles for improvisation, yet it was more significant that the sounds of all instruments were fused in a texture whose parts moved with a supple fluidity that contrasted with the hard, bright, darting lines of bop. The harmonic vocabulary was quite advanced for the jazz )f that time, but the constantly shifting pastel sounds were chiefly the result of orchestration which took some of Evans's procedures with the Thornhill band to their logical conclusion. With trombone, baritone saxophone and tuba, the instrumentation might seem to place undue emphasis on the bottom register, yet, although this obviously does account for the repertoire's dark tone, the absence of a tenor saxophone's rich voice helps to keep the characteristic veiled textures from becoming too cloudy. Further, so far as one can tell without seeing the scores, the most dissonant note in any chord is usually given to the French horn, the softest-voiced of the wind instruments present, and this helped deflect the music's astringency, contributed to the air of remoteness and mystery which it retains even in the most obviously 'exciting' up-tempo moments.

Undoubtedly the most original piece the band recorded was John Carisi's Israel, a modal blues which stands high among the recorded classics of jazz. But Evans's contributions run it close, and in Moon-dreams the very brevity of the solo passages, by Konitz and Mulligan, emphasize that this is an essentially orchestral conception, in fact a study of slow-moving harmonies crossed with subtle changes of texture. Its sonorous gravity is relieved by a passage wherein the horns ascend and then peel off, leaving Konitz sustaining a high, thin note which contrasts almost dramatically with the full, deep chords that soon engulf it. In the quiet final sequence, against long-sustained harmonies, the horns play odd, disjointed little fragments of phrases which create a pointilliste effect. This passage, which is more effective in the broadcast versions than on the studio recording, is reminiscent of the fragmentary brass phrases under high tremolo strings in Variation II of Strauss's Don Quixote or of the tiny oboe and clarinet phrases snickering around the brass in Variation IV. Strauss also provides a precedent for the melodic independence of Evans's tuba writing, although the climate of feeling the latter projects is far more rarefied in this case, the final vibrant stillness of Moondreams suggesting it to be the ensemble's tribute to their exemplar, Claude Thornhill.

It can scarcely need adding that this score is no mere 'arrangement' of a 'song', but is in the tradition of 'compositions for band', like Beiderbecke's Krazy kat or Thelonious Monk's original version of Epistrophy. All the pieces Davis recorded at these sessions, in fact, are set out as continually developing entities (note the skillfully varied thematic recapitulation of Move), and Evans's other main contribution, Boplicity, is in this respect among the most interesting.

Of all these themes, this seems most perfectly suited to the ensemble's rich yet unadorned sonority, and its atmosphere of trancelike relaxed intensity is somehow heightened by the way at the close of the opening chorus the melody flows on into the first bar of the next, so that Mulligan's baritone saxophone passage starts only in the second bar—a small but delightful metrical surprise. Also noteworthy is the bridge of this second chorus. The first half consists of six bars instead of the expected four and the two main voices start an octave apart before spiraling off into counterpoint; the second half is of four bars and Davis's trumpet most tellingly alludes to the preceding phrase; the final eight bars of this chorus present an interesting variant of the main thematic phrase. The last chorus offers still more variety, with each eight-bar segment treated differently. The first is an exceptionally fine duet between Davis and the ensemble, while in the second he is accompanied only by the rhythm section; the third is a piano solo by Lewis, and the gradually diminishing tonal weight of these twenty-four bars is balanced by the final eight bars' restatement of the chief thematic phrase—which at the same time answers the variant that occupied the same place in the preceding chorus.

If Why do I love you? is a far less perfect score this is because it has to accommodate Kenny Hagood's singing, but the final chorus still consists of a strikingly oblique restatement of—or rather allusion to—the original melody, another of Evans's written 'improvisations'.

Even if this music's commercial failure was unavoidable—and the band's library included several more excellent pieces unmentioned above, such as Lewis's Rouge, Mulligan's Rocker and George Wallington's Godchild— it still might have been expected, in view of its wealth of new resources, to affect other jazzmen. This it scarcely did at all. Echoes may be caught on the J. J. Johnson date of several years later which recorded Lewis's Sketch I, but as this had Lewis at the piano, and as both he and the trombonist had been in the Capitol group, this may be considered a direct descendant. A similar comment obviously applies to the Mulligan 1951 session which used two baritone saxophones, and to his later Tentet recordings. Almost .the only examples of indirect influence are a few virtually forgotten Shorty Rogers pieces such as Wail of two cities and Baklava bridge, and some Hal McKusick items discussed on another page. The jazz community, in fact, turned aside, as so often, from an area of potentially major growth, and the error was confirmed by the jazz press of that time, which disliked the Capitol titles because of their refusal to sink into some convenient pigeonhole. Altogether, people began to forget about Gil Evans: his brilliance had been made obvious, but several years passed before anyone was reminded of the fact.

Not that Evans was concerned. True, he did little recording work, but that was because he refused to write for less than the musicians' union standard fee—a trait unlikely to endear him to the artist and repertoire departments of certain companies. But he scored music for radio and tv, for nightclub acts and for what was left of vaudeville. Such records as he did arrange were mainly backgrounds for rather obscure singers like Marcy Lutes, Helen Merrill and Lucy Reed, though he did write a subtly evanescent, hauntingly memorable re-composition of You go to my head for Teddy Charles's Tentet LP, and, later still, Blues for Pablo and Jambangle for Hal McKusick. For the rest, Evans, a self-taught musician—though he insists that "everybody who ever gave me a moment of beauty, significance, excitement has been a teacher" (Quoted in the sleeve note of Gil Evans, Great Jazz Standards, American Pacific Jazz 28) —filled gaps in his education, "reading music history, biographies of composers, articles on criticism, and listening to records" (Hentoff, Ibid). There were other reasons for his relative non-participation in jazz at that time. As he said, "I have a kind of direction of my own .. . my interest in jazz, pop and sound in various combinations has dictated what I would do at various times. At different times, one of the three has been stronger" (Hentoff, Ibid.). Such an attitude would obviously prevent Evans from being a member of any self-conscious and organized movement in music for any length of time, and it may be added that he has never been overly concerned with the 'importance' of his writing, as a lot of it has been done not so much as personal expression as in pursuance of further knowledge through learning in a practical way.

One is not surprised to find, therefore, that he writes slowly through a conscientious desire to avoid clichés: "I have more craft and speed than I sometimes want to admit. I want to avoid getting into a rut. I can't keep doing the same thing over and over. I'm not a craftsman in the same sense as a lot of writers I hear who do commercial and jazz work. They have a wonderful ability with the details of their craft. The details are all authentic, but, when it's over, you realize that the whole is less than the sum of the parts" (Hentoff, Ibid). Because his writing is so individual, Evans has always found it necessary to rehearse his scores personally, and desirable to work with musicians of his own choosing. Mulligan comments on this: "Gil is the one arranger I've played who can really notate a thing the way a soloist would blow [play] it. ... For example, the down-beats don't always fall on the down-beats in a solo, and he makes a note of that. It makes for a more complicated notation, but, because what he writes is melodic and makes sense, it's not hard to play. The notation makes the parts look harder than they are, but Gil can work with a band, can sing to them what he wants, and begets it out of them" (Hentoff, Ibid.). It remains as difficult, however, to obtain an exact description of Evans's rehearsal and recording processes as it was of Ellington's. "No, no, it's more mysterious than that" protested Steve Lacy when, talking to him in London during the mid-1960s, the present writer probed with a series of technical questions. "You get so carried away by the feeling of his music that you lose sight of the details" (Jazz Monthly, March, 1966). In a sort of confirmation of this, Mulligan said that what attracted Charlie Parker to Evans's music was the exploratory stance it adopted. Later he wanted to play some of Evans's scores but, says the latter, "by the time he was ready to use me I wasn't ready to write for him. I was going through another period of learning by then" (Nat Hentoff, Ibid.)

Fortunately, he was ready for some more jazz by 1957, when Miles Davis decided to make an orchestral LP. Considering the lyrical fragility of the trumpeter's best work up till then, Miles Ahead may have seemed an unproductive idea, but what he wanted was to explore further the lines opened up by the Capitol sessions, especially as nobody else had troubled. Boplicity, in particular, had already demonstrated the perfect understanding between Davis and Evans, and the latter's collaboration was clearly essential. They decided to record ten pieces: John Carisi's Springsville, The maids of Cadiz, by Delibes, Dave Brubeck's The Duke, My ship by Kurt Weill, Davis's Miles ahead, Blues for Pablo by Evans, Ahmad Jamal's new rumba, The meaning of the blues by Bobby Troup, J.J.Johnson's Lament and a rather inconsequential Spina/Elliott standard called I don't wanna be kissed. Evans scored these as a series of miniature concertos for Davis, but fused them together in a continuous aural fresco whose connective resonance and authority gain strength with each addition. It sometimes is hard to isolate where one piece ends and another starts, but this principle of merging performances, discovered apparently during work on Miles Ahead, was taken further on subsequent LPs, eventually leading to a fusing of all other elements in his music.

Evans devised an interesting extension of the Capitol sessions' instrumentation, a telling variant of that used by Thornhill: apart from Davis, who played flugelhorn, there were five trumpets, three tenor trombones, bass trombone, two French horns, tuba, two clarinets doubling flutes, bass clarinet, alto saxophone, string bass and percussion. These are treated largely as a body of individual players, and the chords are composed of the most varied tone-colors, which are dealt with according to their natural intensity, some being allowed greater prominence than others. In this respect one is reminded of Schoenberg's Funf Orchesterstucke Op. 16, especially No. 2, and it indicates the development of Evans's musical language that whereas Moondreams is reminiscent of aspects of Richard Strauss, here one thinks of Schoenberg. Miles Ahead has received so much attention elsewhere (For example, Andre’ Hodier, see note 4; Charles Fox: ‘Experiment with Texture’ in Jazzmen of Our Time, edited by Robert Horricks, London, 1959; Max Harrison, “Miles Davis – A Reappraisal’ in This is Jazz, edited by Kenneth Williamson, London, 1960) that comment on separate movements is unnecessary, though the scoring's effect is often that of light imprisoned in a bright mineral cave, its refinement such that at times the music flickers deliciously between existence and non-existence. No matter how involved the textures, though, it always is possible to discover unifying factors as an altogether remarkable ear is in control, ruthlessly—and almost completely—eliminating clichés. Complaints that these Davis/Evans collaborations produced un-rhythmic music were due to faulty hearing, and the widely quoted metaphorical description of the textures as "port and velvet" (Whitney Balliett, The Sound of Surprise, New York, 1959) is inept. Despite its richness, the orchestral fabric is constantly on the move, horizontally and vertically; it is unfortunate that some listeners cannot hear music's pulse unless it is stated as a series of loud bangs. The introverted mood of several panels in the Miles Ahead fresco had been anticipated by Ellington pieces such as Blue serge, and the underlying clarity of Evans's constructions is revealed by setting this version of Blues for Pablo beside the one earlier recorded by a Hal McKusick small group. Both preserve the same relationships between themes, tempos, degrees of textural density, etc., and form an amusing comment on the notion that Evans provided Davis merely with vague impressionistic backgrounds.

In fact, and even though one may object to the show business mentality which lies behind the phrase, he had made the most remarkable comeback in jazz history. Soon his imitators were demonstrating how inimitable his methods were, some of the worst examples being Ernie Wilkins's scores for the Map of Jimmy Cleveland LP (American Mercury MG20442) and certain Bill Matthieu pieces for Stan Kenton's band, especially Willow weep for me, The meaning of the blues (both with Rolf Ericson assuming the Miles Davis role) and Django (All on American Creative World ST1049). All these simply fit together various elements learnt—by rote, as it were—from Evans, whereas his scores are developing musical organisms which establish and proceed from premises of their own.

Further collaborations with Davis followed. Some, like the Quiet Nights disc, exposed the partnership's weaknesses, and Evans's boring re-write of the first movement of Rodrigo's Concierto de Aranjuez. was a strange miscalculation. So, too, was the bogus flamenco of Saeta and Solea, although these were solo vehicles for Davis in which Evans had little part. The last three items are on the Sketches of Spain LP, but an altogether finer expression of Evans's taste for Iberian music is Lotus land, a track on the Guitar Forms record that he made with Kenny Burrell (American Verve MGV8612). However, before either Quiet Nights or Sketches of Spain came Porgy and Bess, which contains, at least in potential, the finest music Davis and Evans recorded together.

Of course, in its original form Gershwin's opera takes up an entire evening, but the excerpts Evans and Davis selected are put together in such a way as to summarize the drama's several aspects. They show, also, that the original music has deeper roots than Gershwin's detractors concede—deeper, perhaps, than he himself knew. On certain items, such as Prayer or My man's gone now, occurs some of the most eloquent playing Davis ever recorded, and though Evans frequently sets dark, massed sonorities against the trumpeter's passionate self-communing, there is some exquisite scoring, too, as in Fishermen, strawberry and devil crab or Here comes the honey man. Hear, also, Davis's re-reading of It ain't necessarily so, whose meaningful obliqueness is set oil by staccato French horn chords—Evans for once using a conventional device.

Although the Porgy and Bess LP contains magnificent jazz—and one plays some tracks over and over, as if to savor a rare essence—the performances left even more to be desired than those of Miles Ahead. One cannot be sure about such things without seeing the scores (and it is a perpetual handicap to the proper musicological study of jazz that scores are never obtainable), but one of the musicians who played on the Porgy and Bess dates shortly afterwards said the following in a private communication to the present writer:

"The crux of the matter is that Gil, on both sets of dates, did not rehearse carefully enough, as is evident already on Miles Ahead. I believe this is mostly the result of the unfortunate conditions under which American recording is done. It is too costly for any project of more than average difficulty to be done well, unless the music in question is rehearsed before the date (which is illegal according to union rules), or has been previously performed.

"Under these, to say the least, less than ideal circumstances, both Miles and Gil have a too relaxed attitude about accomplishing the tasks they set themselves. In pieces which are scored as sensitively and as intricately as Gil's, it's a shame to let the performances cancel out half of their effectiveness. Many details of scoring simply could not be—or at least were not—touched upon in the sessions I was on. Some things were left undone which I would not have let go.

"But, as I've indicated, the blame lies more with the conditions than the people. And I suppose one could say that it is remarkable that both LPs are as good as they are. If Gil were a better conductor it would also help: he sometimes confused the players. On the other hand, he is quite patient—perhaps too much so for his own good—and very pleasant to work for. Whatever excellence these recordings possess I would attribute (aside from Gil's own magnificent scores, of course) primarily to the supreme abilities of some of the leading players, like Ernie Royal [trumpet], Bill Barber [tuba], the very fine reed men (on all manner of flutes and bass clarinets), and in general the respect which all of us, despite what I've said above, have for Gil Evans."

Such problems were considerable, yet Evans solved them with alacrity—indeed as soon as he began making records under his own name instead of in partnership with Davis. One or two items on his first, Gil Evans plus Ten (Several Evans LPs have been given misleading new titles on reissue. …), such as Remember or Nobody's heart, may appear to continue the line of ballad scores he wrote for Thornhill, as if he were recapitulating before going on to something new, but in fact the material ranged from Ella Speed, associated with the folksinger Huddie Leadbetter, to Tadd Dameron's If you could see me now. A commitment to the present is enriched by a sense of the past, and this marked the beginning of a personal reassessment of the jazz repertoire, and from his next record, New Bottle Old Wine, onwards Evans turned his back on non-jazz themes. The latter disc conducts a miniature history of jazz, running from W. C. Handy's St Louis blues to Bird feathers by Charlie Parker, but Evans makes all eight compositions his own while paradoxically preserving their original extremely diverse characters; by a further paradox, he appears to give his chief soloist complete freedom while clearly remaining in control of every bar. That soloist is 'Cannonball' Adderley, a minor disciple of Parker, and so this LP gives a hint of what might have happened if Evans had been able to work with the great altoist himself. In the event, several others, including the trombonist Frank Rehak in Strutting with some barbeque and Chuck Wayne, the guitarist, on Lester leaps in, outclass Adderley, and Evans's writing provides so stimulating and enriching a commentary as almost to swamp them all.

Certainly it is untrue to assert, as some writers have, that he needs a soloist to focus his processes around. In St Louis blues, though Adderley appears to hold the centre of the stage, the shifting, tirelessly inventive background is of such fascination, what with Evans's characteristic reshaping of the themes, his alterations to the harmony, and such details as the independent guitar or tuba lines, that the listener soon finds himself attending not to the soloist but to the 'accompaniment'. And in King Porter stomp, also, how much further Evans goes in such matters than, say, Henderson in his arrangement of this piece for Goodman's band: to speak of variations on the themes would be too formal a description of a process so free, and here again we have written 'improvisations' in exactly the sense that George Russell meant (6). The same is true of all the other tracks, which teem with interest and range from the quietly luminous sensitivity of Fats Waller's Willow tree to the violent assertion of Dizzy Gillespie's Manteca, whose virtuoso brass writing the players throw of! with such apparently casual ferocity.

On Evans's next LP, Great Jazz Standards, the soloists got closer to holding their own. Johnny Coles has a beautiful trumpet solo in Bix Beiderbecke's Davenport blues, as does Steve Lacy, on soprano saxophone, in Monk's Straight, no chaser. Yet Budd Johnson does better still, his rounded clarinet phrases contrasting with the abrupt whole-tone lines of Don Redman's Chant of the weed, the solid 4/4 of his tenor saxophone solo on Evans's Theme being excellently set off by complex brass figures. To how much better advantage does Johnson appear in these surroundings, or on Evans's Out of the Cool record, than in the dreary 'mainstream' sessions (For example, Budd Johnston, Blues a la Mode, American Felstead FAJ7007) which usually are this neglected musician's lot! Evans can use these and other soloists in pieces which are far removed from their normal style or period—e.g. Coles on Davenport blues—without any incongruity because the material is so transformed, the vision so strong as to unify everything. His orchestration of Straight, no chaser is far more to the point, though also far more elaborate, particularly the final ensemble, than previous attempts, by Hall Overton and others (For instance Monk at Town Hall, American Riverside RLP-12-300), to score Monk themes, and throughout this LP the level of invention, yet again, is amazingly high, above all in the lengthy and very searching treatment of John Lewis's Django. Hear, too, the ensemble textures in Ballad of the sad young men—massive yet without any hint of inflexibility. It is the same on the next record, Out of the Cool, which contains, for example, a hypnotically prolonged When flamingoes fly, whose acute melancholy is etherealized, dissolved. Such pieces well accord with Claude Levi-Strauss's view of music as ‘a machine for the suppression of time' (Claude Levi-Strauss, Le Cru et le Cuit, Paris, 1974), and embody a more authentically modern sensibility than a lot of more overtly dissonant jazz.

From this point on there is a striking loosening-up of Evans's music, comparable only to that undergone by George Russell's work after he began to make his Sextet discs for the Riverside label. Consider, for instance, the much freer treatment of the background riff in Summertime on the Svengali LP in comparison with the earlier version on the Porgy and Bess disc. No longer is Evans concerned with mathematical symmetry or balanced repetition, but rather, it seems, with a reflection of the mysterious complexity of the forms of nature, in particular nature's love of analogy instead of repetition. The lyrical tenor saxophone 'solos' by Wayne Shorter in Barbara story on The Individualism of Gil Evans two-LP set or by Billy Harper in the Ampex General assembly are only single threads in textures which now defy both description and analysis; the music is a seamless web in which lines cross and re-cross, glowing, opalescent colours come and go in inexhaustible combinations. Hear, for example, the magically woven fabric of Hotel me on the Individualism set, the exquisite beauty of even the tiniest details of the Ampex Proclamation. On these later recordings identification between the music and the individual performers is so complete that, especially in deep, multi-voiced ensembles like those of Concorde, it is impossible to guess where writing stops and improvisation begins. There is an extraordinary reconciliation, or rather a shifting balance between freedom and control whose philosophical implications go beyond jazz, beyond music.

At this stage each Evans record is 'untypical' because he sets himself different objectives every time. But despite this constant renewal, there are still lines of continuity. Thus Joe Beck, guitarist on the Ampex date, occupies a position midway between horns and rhythm section like that of Ray Crawford in Out of the Cool or Barry Galbraith on the Russell/McKusick LPs. In fact this music increasingly happens on several levels at once, recalling the multiplicity of events in Charles Ives's works. For instance on Las Vegas tango, a gravely serene piece from the Individualism set, things happen close up, in sharp focus, others take place in the middle distance, some murmur far away on the horizon, and the exactness of Evans's aural imagination is such that we can hear it all, every note, every vibration, carrying significance. Yet one gains the impression that he feels music, like other forms of truth, should never be immediately understood, that there should always remain some further element to be revealed. Note the gradual, almost reluctant, disclosure of the melodies of La nevada and Bilbao song, or the way the theme of Joy spring is not heard until right at the end.

These endings, many of which fade, like beautiful sunsets, as we look at them, in turn suggest by their very inconclusiveness that Evans, again like Ives, has an Emersonian dislike of the spiritual inactivity which comes from the belief that one possesses a truth in its final form. It is tempting, to think that in achieving the lyrical resignation of Flute song or the alert tranquility of Barbara story Evans uses sounds rather as Mallarme uses words—as mirrors that focus light from a hundred different angles on to his precise meaning. But they remain symbols of meaning rather than the meaning itself, and much is left to the imagination. If the listener is unwilling, or, worse still, unable, to exercise this faculty then he will soon be left behind.

Jazz Monthly, December 1958 and February 1960”

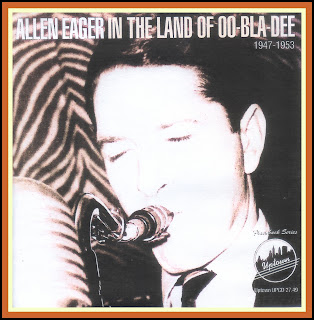

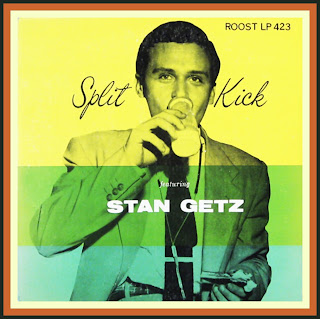

Perhaps the key difference between, say Dexter and Getz, was that Gordon had also listened profitably to Hawkins, Webster and Byas, while Stan appeared to be a Pres man and a Dexter Gordon admirer! Ideas were exchanged more readily in those days and to unravel the cross-pollination of musical thought that went on between the guys involved would be impossible now.

Perhaps the key difference between, say Dexter and Getz, was that Gordon had also listened profitably to Hawkins, Webster and Byas, while Stan appeared to be a Pres man and a Dexter Gordon admirer! Ideas were exchanged more readily in those days and to unravel the cross-pollination of musical thought that went on between the guys involved would be impossible now. But we can examine a goodly slice of recorded evidence, enjoyable clues and pointers and fine music to boot, within the covers of this key reissue. In this set can be heard a superstar in embryo (Stan Getz). a living legend (Allen Eager), two departed legends (Brew Moore, Serge Chaloff), Mr. Swing (Zoot Sims), and the complete musician, composer/arranger/soloist (Al Cohn), They all happened to be saxophonists who came to prominence immediately after the war. Four-Cohn, Getz, Sims and Chaloff-were Brothers in the famous Herman bebop hand. Moore (he never worked with Herman) was a brother by adoption while Eager had been a member of Woody's saxophone section in 1944.

But we can examine a goodly slice of recorded evidence, enjoyable clues and pointers and fine music to boot, within the covers of this key reissue. In this set can be heard a superstar in embryo (Stan Getz). a living legend (Allen Eager), two departed legends (Brew Moore, Serge Chaloff), Mr. Swing (Zoot Sims), and the complete musician, composer/arranger/soloist (Al Cohn), They all happened to be saxophonists who came to prominence immediately after the war. Four-Cohn, Getz, Sims and Chaloff-were Brothers in the famous Herman bebop hand. Moore (he never worked with Herman) was a brother by adoption while Eager had been a member of Woody's saxophone section in 1944. In his usual clever way Woody Herman adapted an idea for his own purposes. As early as the beginning of 1946 Gene Roland organized a band with four tenors in the lineup-Al Cohn, Stan Getz, Joe Magro and Louis Otis. In the summer of the following year he revived the idea at a place called Pontrelli's Ballroom, Los Angeles. By then the saxophone personnel comprised Getz, Sims, Steward and Jimmy Giuffre. Ralph Burns heard them and was impressed. He persuaded Woody to go along and listen. Result: Herman put Getz, Sims and Steward on the payroll and replaced Giuffre with Chaloff. The astute leader had bought himself a distinctive feature for the band that was ultimately launched in October 1947. Well, did all those white tenor players sound the same. as Miles Davis once asserted? Not on your life but they did have much in common, not least their respect for Pres. And when several of them played together and traded breaks it could be confusing. As an exercise try pinpointing the soloists on every segment of a Stan Getz date from April 1949 which brought together Getz, Cohn, Eager, Moore and Sims. It is a tough blindfold test.

In his usual clever way Woody Herman adapted an idea for his own purposes. As early as the beginning of 1946 Gene Roland organized a band with four tenors in the lineup-Al Cohn, Stan Getz, Joe Magro and Louis Otis. In the summer of the following year he revived the idea at a place called Pontrelli's Ballroom, Los Angeles. By then the saxophone personnel comprised Getz, Sims, Steward and Jimmy Giuffre. Ralph Burns heard them and was impressed. He persuaded Woody to go along and listen. Result: Herman put Getz, Sims and Steward on the payroll and replaced Giuffre with Chaloff. The astute leader had bought himself a distinctive feature for the band that was ultimately launched in October 1947. Well, did all those white tenor players sound the same. as Miles Davis once asserted? Not on your life but they did have much in common, not least their respect for Pres. And when several of them played together and traded breaks it could be confusing. As an exercise try pinpointing the soloists on every segment of a Stan Getz date from April 1949 which brought together Getz, Cohn, Eager, Moore and Sims. It is a tough blindfold test. Incidentally, it is interesting to note that Young himself thought that Paul Quinichette and "maybe Eager" came nearest to his own style. Pres remains an enigma-but then so do Moore and Eager, two highly unconventional characters whose restless lifestyles typified their time. Milton A. Moore Jr. was a wanderer, a born loser, a hero of the beat generation and a brilliant saxophonist. Yes, he once remarked that any tenorman who did not play like Pres was playing wrong-that was the extent of his admiration.

Incidentally, it is interesting to note that Young himself thought that Paul Quinichette and "maybe Eager" came nearest to his own style. Pres remains an enigma-but then so do Moore and Eager, two highly unconventional characters whose restless lifestyles typified their time. Milton A. Moore Jr. was a wanderer, a born loser, a hero of the beat generation and a brilliant saxophonist. Yes, he once remarked that any tenorman who did not play like Pres was playing wrong-that was the extent of his admiration. Moore was born in Indianola, Mississippi, on March 26, 1924, and his first musical instrument was a harmonica given to him by his mother as a seventh birthday present. He played in his high school band and at 18 got a job with Fred Ford's dixieland band. He arrived in New York during 1943 and heard what bebop was all about. He would return to New York several times in the late forties to lead his own quartet, work with Claude Thornhill (an unlikely environment), swing his tail off in front of Machito's Afro-Cubans, gig with Gerry Mulligan and Kai Winding at the Royal Roost and Bop City.

Moore was born in Indianola, Mississippi, on March 26, 1924, and his first musical instrument was a harmonica given to him by his mother as a seventh birthday present. He played in his high school band and at 18 got a job with Fred Ford's dixieland band. He arrived in New York during 1943 and heard what bebop was all about. He would return to New York several times in the late forties to lead his own quartet, work with Claude Thornhill (an unlikely environment), swing his tail off in front of Machito's Afro-Cubans, gig with Gerry Mulligan and Kai Winding at the Royal Roost and Bop City. One day in the 'fifties Brew casually took off for California. As Moore told it, "Billy Faier had a 1949 Buick and somebody wanted him to drive it out to California and he rode through Washington Square shouting 'anyone for the Coast?' And I was just sitting there on a bench and there wasn't shit shaking in New York so I-said 'hell, yes,' and when we started off there was Rambling Jack Elliot and Woody Guthrie." After Woody heard Brew play at the roadside en route he refused to speak again to the saxophonist.

One day in the 'fifties Brew casually took off for California. As Moore told it, "Billy Faier had a 1949 Buick and somebody wanted him to drive it out to California and he rode through Washington Square shouting 'anyone for the Coast?' And I was just sitting there on a bench and there wasn't shit shaking in New York so I-said 'hell, yes,' and when we started off there was Rambling Jack Elliot and Woody Guthrie." After Woody heard Brew play at the roadside en route he refused to speak again to the saxophonist. Before that fantastic journey. Brew had worked around with his buddy Tony Fruscella, a beautiful trumpeter who was also over-fond of the juice. Allen Eager was also a regular playing partner of Fruscella's. Brew stayed in Frisco for about five years, played all over town, made a couple of albums under his own name, recorded with Cal Tjader and drank a lot of wine. He was seriously ill in 1959 but recovered and in 1961 moved to Europe and for three years drifted around the Continent. Twice in the 1960's he returned to the States but there was still no shit shaking and nobody bothered to record him properly (a date as a sideman with Ray Nance was the only evidence of the final, unhappy return). His parents were very old and his mother sick. Brew was far from well and didn't look after himself. Friends kept an eye on him and tried to ensure that he ate regularly but Moore was almost past caring.

Before that fantastic journey. Brew had worked around with his buddy Tony Fruscella, a beautiful trumpeter who was also over-fond of the juice. Allen Eager was also a regular playing partner of Fruscella's. Brew stayed in Frisco for about five years, played all over town, made a couple of albums under his own name, recorded with Cal Tjader and drank a lot of wine. He was seriously ill in 1959 but recovered and in 1961 moved to Europe and for three years drifted around the Continent. Twice in the 1960's he returned to the States but there was still no shit shaking and nobody bothered to record him properly (a date as a sideman with Ray Nance was the only evidence of the final, unhappy return). His parents were very old and his mother sick. Brew was far from well and didn't look after himself. Friends kept an eye on him and tried to ensure that he ate regularly but Moore was almost past caring. Allen was soon deeply involved in the nightly happenings on 52nd Street where a string of clubs offered the new sounds in jazz. The young tenorman, with a devotion to the Lestorian Bible, earned the respect of older players. On a Saturday evening in September 1945 an incredible six-hour show was presented by Monte Kay and Symphony Sid at the Fraternal Clubhouse, which signaled the new musical order to returnees from the European and Pacific theatres of war. Drummer Big Sid Catlett got top billing, but the "Sensational All-Star Orchestra" also included Buck Clayton and Al Killian (trumpets), Trummy Young (trombone), Charley (sic) Parker (alto), Dexter Gordon (tenor), Tony Sciacca (Scott) (clarinet), Al Haig and Billy Taylor (pianos), Len Gaskin and Lloyd Trottman (basses), Tiny Grimes (guitar) and J.C. Heard (drums). Under this impressive list on the posters ran the line, "Introducing Allen Eager on Tenor Sax."

Allen was soon deeply involved in the nightly happenings on 52nd Street where a string of clubs offered the new sounds in jazz. The young tenorman, with a devotion to the Lestorian Bible, earned the respect of older players. On a Saturday evening in September 1945 an incredible six-hour show was presented by Monte Kay and Symphony Sid at the Fraternal Clubhouse, which signaled the new musical order to returnees from the European and Pacific theatres of war. Drummer Big Sid Catlett got top billing, but the "Sensational All-Star Orchestra" also included Buck Clayton and Al Killian (trumpets), Trummy Young (trombone), Charley (sic) Parker (alto), Dexter Gordon (tenor), Tony Sciacca (Scott) (clarinet), Al Haig and Billy Taylor (pianos), Len Gaskin and Lloyd Trottman (basses), Tiny Grimes (guitar) and J.C. Heard (drums). Under this impressive list on the posters ran the line, "Introducing Allen Eager on Tenor Sax." During much of 1945 Eager and Gray worked together as members of the Tadd Dameron Band at the Royal Roost. The two saxophonists' differing stances on the Young/ Parker innovations made for a fascinating contrast. "Eager was not merely an imitator, however," wrote Gitler. "He had his own interpretation of Pres's style, and already other elements, like Charlie Parker, were changing it more. Whatever he played swung with a happy, light-footed quality and pure toned beauty. His interior time was equal to his fine overall swing. Many a night in the Roost, he had us ready to get up and start dancing along the bar."

During much of 1945 Eager and Gray worked together as members of the Tadd Dameron Band at the Royal Roost. The two saxophonists' differing stances on the Young/ Parker innovations made for a fascinating contrast. "Eager was not merely an imitator, however," wrote Gitler. "He had his own interpretation of Pres's style, and already other elements, like Charlie Parker, were changing it more. Whatever he played swung with a happy, light-footed quality and pure toned beauty. His interior time was equal to his fine overall swing. Many a night in the Roost, he had us ready to get up and start dancing along the bar." During the late 1960's Eager was reported as being involved with the "flower people" on the West Coast. He had taken up soprano saxophone and was apparently sitting in with the Mothers of Invention on occasion. Since then the Eager Trail has gone cold. Allen has become a sort of

During the late 1960's Eager was reported as being involved with the "flower people" on the West Coast. He had taken up soprano saxophone and was apparently sitting in with the Mothers of Invention on occasion. Since then the Eager Trail has gone cold. Allen has become a sort of Stan Getz, the youngest of the five tenor saxophonists celebrated in this edition, was definitely the most precocious. He was a teenage prodigy and for him too much came too soon. Born in Philadelphia on February 2, 1927. Getz started on bass, then switched to bassoon, but when he joined Dick "Stinky" Rogers at 15 he was playing tenor sax. Stan packed away a lot of experience in those early years working with Jack Teagarden, Dale Jones, Bob Chester, a year with Stan Kenton, Randy Brooks, Buddy Morrow, Jimmy Dorsey and Benny Goodman. By the time he signed on with Woody Herman, Getz was well known and had recorded under his own name. His acknowledged favorite has always been Lester but, as already noted, he also drew heavily on Dexter Gordon's vocabulary at one point.

Stan Getz, the youngest of the five tenor saxophonists celebrated in this edition, was definitely the most precocious. He was a teenage prodigy and for him too much came too soon. Born in Philadelphia on February 2, 1927. Getz started on bass, then switched to bassoon, but when he joined Dick "Stinky" Rogers at 15 he was playing tenor sax. Stan packed away a lot of experience in those early years working with Jack Teagarden, Dale Jones, Bob Chester, a year with Stan Kenton, Randy Brooks, Buddy Morrow, Jimmy Dorsey and Benny Goodman. By the time he signed on with Woody Herman, Getz was well known and had recorded under his own name. His acknowledged favorite has always been Lester but, as already noted, he also drew heavily on Dexter Gordon's vocabulary at one point. For much of 1947 he was in California, blowing with Butch Stone and his own trio at the Swing Club. His solos with Herman, especially on Early Autumn, gained him immediate recognition and he was soon winning music polls. By 1949 he was able to form his own small group and in the early 1950's he had what many listeners regard as his finest band with Al Haig, Jimmy Raney, Teddy Kotick and Tiny Kahn, They called him "The Sound," and he certainly did have a compelling and original tone, much further removed from Pres than Eager or Moore. Getz frequently toured with

For much of 1947 he was in California, blowing with Butch Stone and his own trio at the Swing Club. His solos with Herman, especially on Early Autumn, gained him immediate recognition and he was soon winning music polls. By 1949 he was able to form his own small group and in the early 1950's he had what many listeners regard as his finest band with Al Haig, Jimmy Raney, Teddy Kotick and Tiny Kahn, They called him "The Sound," and he certainly did have a compelling and original tone, much further removed from Pres than Eager or Moore. Getz frequently toured with Cohn was born in Brooklyn on November 24, 1925 (two years to the day after Serge Chaloff) and cut his teeth on clarinet, an instrument he still uses sometimes. In fact he never actually studied tenor saxophone but picked up his own playing technique. His first job was with Joe Marsala, then came a spell as soloist and arranger with Georgie Auld's Band, followed by jobs with Alvino Rey and Buddy Rich. He replaced Herbie Steward in the Herman Herd and remained from January 1948 to April 1949 yet was not featured on any of Woody's records. Next stop was to a fine Artie Shaw Orchestra where he did cop some solo space. He left music for a couple of years but returned to play with Elliot Lawrence in 1952, Subsequently he did all manner of music jobs, writing for radio and television, making numerous records as soloist and arranger, and often teaming up with old friend Zoot Sims for, club work. He has recently returned to active playing again and sounds as good as ever. Cohn's tone has darkened and got heavier over the years but he still swings a la Lester. Through the years he has hewn close to the broad tenets that shaped his style from the outset. You can always rely on Cohn to make you feel good with his driving, purposeful swing and uncliched ideas.

Cohn was born in Brooklyn on November 24, 1925 (two years to the day after Serge Chaloff) and cut his teeth on clarinet, an instrument he still uses sometimes. In fact he never actually studied tenor saxophone but picked up his own playing technique. His first job was with Joe Marsala, then came a spell as soloist and arranger with Georgie Auld's Band, followed by jobs with Alvino Rey and Buddy Rich. He replaced Herbie Steward in the Herman Herd and remained from January 1948 to April 1949 yet was not featured on any of Woody's records. Next stop was to a fine Artie Shaw Orchestra where he did cop some solo space. He left music for a couple of years but returned to play with Elliot Lawrence in 1952, Subsequently he did all manner of music jobs, writing for radio and television, making numerous records as soloist and arranger, and often teaming up with old friend Zoot Sims for, club work. He has recently returned to active playing again and sounds as good as ever. Cohn's tone has darkened and got heavier over the years but he still swings a la Lester. Through the years he has hewn close to the broad tenets that shaped his style from the outset. You can always rely on Cohn to make you feel good with his driving, purposeful swing and uncliched ideas. Completing the cast of brothers in the present collection is the sixth saxophonist Serge Chaloff. the baritone anchorman of the Herman sax section. Born in Boston in 1923, Chaloflf came from a musical background and he studied piano and clarinet but, like Cohn, was a self-taught saxophonist, originally inspired by Harry Carney and Jack Washington. Chaloff had an incredible technique on the large saxophone, one that was never quite matched by even his distinguished contemporaries Leo Parker and Cecil Payne. Serge worked through the ranks of the Tommy Reynolds, Stinky Rogers, Shep Fields and Boyd Raeburn bands. But after hearing Charlie Parker his ideas were drastically altered, and in the orchestras of Georgie Auld and Jimmy Dorsey he was rapidly identified as a Brothers superior bop soloist, a status that was emphasized when he worked with Herman. After the years with Woody, Serge retreated to Boston and then moved to California. He was another narcotics victim but he actually died of cancer on July 16. 1957. His last recordings exhibit a remarkable control of the horn and. emotionally, they are among some of the most moving performances in jazz. Chaloff was undoubtedly one of a kind and now it seems ludicrous that in the public's mind he came second to Gerry Mulligan. a good player but one who lacked the originality of Chaloff.