© - Steven A. Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

CHARLES ELLSWORTH "PEE WEE" RUSSELL

Born: St. Louis, Mo., March 27, 1906

Died: Alexandria, Va., February 15, 1969

Musician - Legend - Jazz Original

“Dry facts, as on a tombstone. But looking deeper, one finds a tumultuous 63 years of bohemian life, crowded with agonies, friendships and loyalties, drinking, much wandering, life-long physical problems, and even romance. And running through this chaotic landscape a vitalizing river of music - jazz music. In his lifespan it evolved from ragtime into the varied styles of the 'modern" Sixties. He lived and played through just about all of it, and in doing so had a clear influence on the music itself. He's now a legend: ole shy, backing-away Pee Wee, with the rumbling, many-toned speaking voice - and a clarinet sound to match it!”

– Joe Muranyi, Jazz clarinetist

“Pee Wee Russell was an odd-duck of a clarinetist who in his idiosyncratic way foreshadowed some of the innovations of modern jazz. His playing at times seems "off" in the way that some of the earliest jazz sounds almost otherworldly with its unique tones and timbres. Russell’s expressive slides and dips pre-figure the likes of the later Lester Young, and in our day Lee Konitz, especially when his playing became more voice-like, and the expectations of others seemed to matter even less. It seems the better Russell played the more idiosyncratic he got. Pee Wee was a natural odd duck.”

“Pee Wee Russell had the most fabulous musical mind. I've never run into anybody who had that much musical talent.”

- Gene Krupa, Jazz drummer and Bandleader

“Russell’s music was never quite what it seemed.”

– Gary Giddins, Jazz author

“Jazz is only what you are.”

– Louis Armstrong

Trumpet players and trombonists talk about mouthpieces, saxophone players talk about reeds, guitarists and bassists talk about strings and drummers talk about sticks and brushes.

These are the devices that make the instruments they play make sounds so each in their own way is curious about how to alter, or improve, or make easier, the production of that sound.

Of course, this is an oversimplification of the elements involved in playing an instrument, but you get the idea.

For me, the “ultimate quest” had to do with improving my brushwork. Using sticks came naturally as I suspect it does for most drummers, but brushes were hard work. They were the ultimate riddle.

Progress was slow for me and I was always looking for ways to enhance the way I played brushes.

When he was on the West Coast for a brief time, I got to know drummer Ron Lundberg, who really helped me refine some aspects of my brushwork.

But it was to be a short-lived learning process for after having gigged and recorded with Barney Kessel in California, Ron left to go back to New York where he played with pianist Marian McPartland’s trio and later with vocalist Mose Allison.

Caught up in my own thing, I lost track of Ron until one day in late 1962 when the postman delivered New Groove: The Pee Wee Russell Quartet [Columbia LP CL 1985; CS 8785]. There was Ron on the cover standing behind a Ferrari “Testa Rosa” along with Marshall Brown [valve trombone and bass trumpet] and bassist Russell George. Pee Wee Russell was seated behind the wheel of this beautiful, white sports car.

The album was a gift from Ron [whose playing on it is outstanding] and it was my first – I know that this is hard to believe – introduction to Pee Russell, whose playing can only be described as ineffable.

Having been “corn fed” a steady “clarinet diet” of Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, Woody Herman, with some Buddy de Franco thrown in for dessert, I had no idea of what to make of the sound that came out of Pee Wee’s – was it a – clarinet?

And yet, at the same time, I was totally captivated and mesmerized by it and I became a instant fan.

This LP opened the door for a journey back through time as I sought out Pee Wee’s earlier recordings. Discovering these was like riding in a time-machine through the history of Jazz.

Eventually I would come to view Pee Wee’s playing as the ultimate Jazz achievement – one of singularity or originality. But for the life of me, when it comes to Pee Wee’s clarinet style, I’ve never been very good at describing what I heard on that record or since. Scintillating and shuddery are the best I can do.

Thank goodness then for the likes of Nat Hentoff, Bill Crow and Whitney Balliett who not only come to my assistance with apt and well-informed descriptions of Pee Wee’s playing, but who also do so from the standpoint of being among those who knew him personally.

For those interested in a more comprehensively detailed biography of Pee Wee and his discography, the definitive treatment appears to be Robert Hilbert’s Pee Wee Speaks [Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1992, Studies in Jazz #13]. Mr. Hilbert’s work begins with a previously undocumented first recording session of 16-year-old Russell in 1922, and ends in 1968 with a Mississippi riverboat party shortly before his death. The discography includes all of his known commercial recordings worldwide as well as much new information on film soundtracks, private recordings, broadcasts, and concerts.

Pee Wee also shares a chapter with his long time running mate trombonist Jack Teagarden in Richard Sudhalter’s well-written and wonderfully informative Lost Chords: White Musicians and Their Contributions to Jazz: 1915-1945 [New York: Oxford University Press, 1992].

In his work, the late Mr. Sudhalter posits and interesting observation about Jack and Pee Wee:

“… Both soon became stylists as easy to recognize as they were difficult to imitate, and their inimitability presents students of jazz history with an intriguing conundrum.

Neither Teagarden nor Russell left a major stylistic progeny. Neither exerted the kind of direct and diversified influence on subsequent jazz players so notable in Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Benny Goodman, Charlie Parker, Roy Eldridge – and, above all, Louis Armstrong.”

Perhaps some answers to this puzzle can be found in the following excerpts about Pee Wee.

Nat Hentoff, Jazz Is, [New York: Limelight Editions, 1991, pp. 12–13].

“Pee Wee Russell, who played jazz with every inch of his thin, elongated body and thereby appeared to be made of rubber as he stretched and twisted during a solo, had a sound unlike that of any other clarinetist in jazz. He made the clarinet growl, rasp, squeak (most of the time deliberately), and then suddenly the horn would whisper, sensuously, delicately, promising even more swirling intimacies to come. And never, ever, was it possible to predict the shapes of what was to come.

One night, in the late 1940's, a student from the New England Conservatory of Music came into a jazz room in Boston where Pee Wee was playing, went up to the stand, and unrolled a series of music manuscript pages. They were covered, densely, with what looked like the notes of an extraordinarily complex, ambitious classical composition.

"I brought this for you," the young man said to Pee Wee Russell. "It's one of your solos from last night. I transcribed it."

Pee Wee, shaking his head, looked at the manuscript. "This can't be me," he said. "I can't play this."

The student assured Pee Wee that the transcribed solo, with its fiendishly brilliant structure and astonishingly sustained inventiveness, was indeed Russell's.

"Well," Pee Wee said, "even if it is, I wouldn't play it again the same way - even if I could, which I can't."”

Bill Crow, From Birdland to Broadway: Scenes from a Jazz Life [New York: OxfordUniversity Press, 1992, pp. 149-153]

Pee Wee Russell

Gerry Mulligan's quartet often played at George Wein's Storyville in the Copley Square Hotel. In the basement of the same hotel, Wein also had a room called Mahogany Hall, where he featured traditional jazz with musicians like Vic Dickenson and Pee Wee Russell. During one year's-end engagement, George wanted to combine both bands in a jam session upstairs at Storyville to welcome the new year. Gerry offered to write an arrangement of "Auld Lang Syne" for the occasion.

Gerry finished the arrangement and called an afternoon rehearsal on the day of New Year's Eve. Pee Wee Russell was worried about reading the music and made suffering noises. He sounded fine, but continued to worry. That night, the musicians from Mahogany Hall came up to jam a few tunes with us before twelve o'clock, and as the hour approached, Gerry called for his chart, but Pee Wee's part was missing. Though we were disappointed, there was nothing we could do. Midnight was upon us. We had to fake a Dixieland version of "Auld Lang Syne." As we left the bandstand afterwards, there on Pee Wee's chair I saw the missing part. The crafty bastard had been sitting on it all the time.

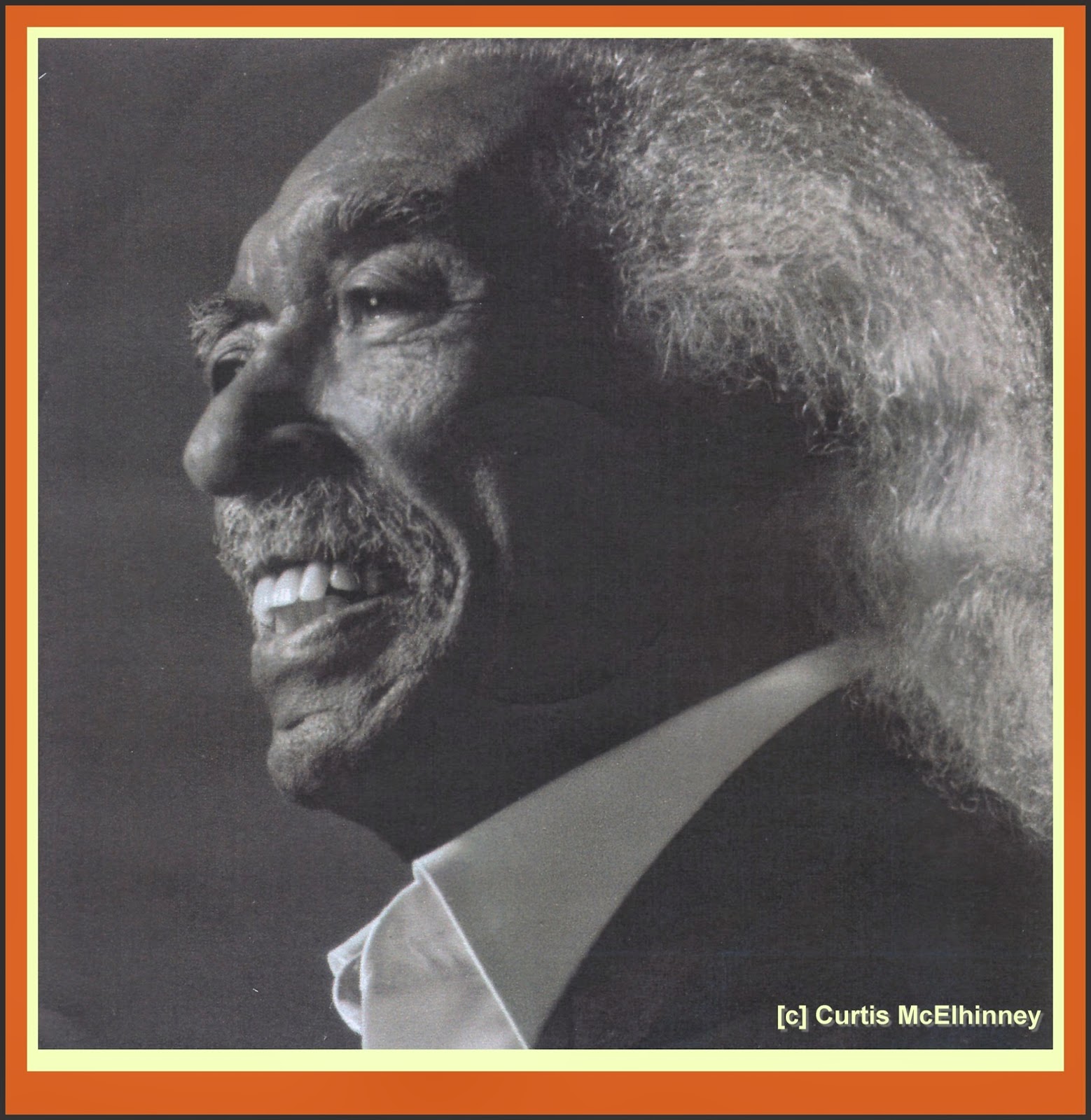

Pee Wee and I were both early risers, so I often met the tall, cadaverous-looking clarinetist for breakfast in the hotel coffee shop. He was talkative at that hour, but it took me a while to catch everything he said. His voice seemed reluctant to leave his throat. It would sometimes get lost in his moustache, or take muffled detours through his long free-form nose.

Pee Wee's playing often had an anguished sound. He screwed his rubbery face into woeful expressions as he simultaneously fought the clarinet, the chord changes, and his imagination. He was respectful of the dangers inherent in the adventure of improvising, and never approached it casually.

Pee Wee's conversational style mirrored the way he played. He would sidle up to a subject, poke at it tentatively, make several disclaimers about the worthlessness of his opinion, inquire if he'd lost my interest, suggest other possible topics of conversation, and then would dart back to his original subject and quickly illuminate it with a few pithy remarks mumbled hastily into his coffee cup. It was always worth the wait. His comments were fascinating, and he had a delightful way with a phrase.

His hesitant and circuitous manner of speaking, combined with his habit of drawing his lanky frame into a concave position that seemed to express a vain hope for invisibility, gave me a first impression of shyness and passivity. I soon discovered that there was a bright intelligence and sense of humor under that facade. Also there was a determined resistance to being pushed in any direction Pee Wee didn't want to go.

I'd heard stories of the many years Pee Wee had spent drinking heavily while playing in the band at Nick's in Greenwich Village. Like many of the musicians of his era, Pee Wee had considered liquor to be an integral part of the jazz life. Over the years, the quantity of booze that he put away eventually wore him down so badly that once or twice he was thought to have died, when in fact he was just sleeping. His diet for years was mainly alcohol, with occasional "meals" that consisted of a can of tomatoes, unheated, washed down with a glass of milk. On the bandstand he always looked emaciated and uncomfortable.

A friend told me that the only time Pee Wee ever came to work sober in those days was once when his wife, Mary, thought she was pregnant. That night Pee Wee arrived at Nick's in good focus, didn't drink all night, and actually held conversations with friends that he recognized. A couple of days later, when Mary found out her pregnancy was a false alarm, Pee Wee returned to his old routine, arriving at work in an alcoholic fog, speaking to no one, alternately playing and drinking all night long.

His health failed him in 1951. Pee Wee was hospitalized in San Francisco with multiple ailments, including acute malnutrition, cirrhosis of the liver, pancreatitis, and internal cysts. The doctors at first gave him no hope for recovery, and word had spread quickly through the jazz world that he was at death's door. It was reported in France that he had already passed through it. Sidney Bechet played a farewell concert for him in Paris.

Eddie Condon described the surgery that saved Pee Wee's life:

"They had him open like a canoe!”

Condon also was quoted as saying, "Pee Wee nearly died from too much living."

At any rate, Pee Wee miraculously rallied, recovered, and limped back to New York. When they heard of his illness and that he was broke, musicians in California, Chicago, and New York gave benefit concerts that raised around $4,500 to help with his medical expenses. Louis Armstrong and Jack Teagarden visited his hospital room in San Francisco and told him about the benefit they were planning. Pee Wee, sure that he was expressing his last wish, whispered, "Tell the newspapers not to write any sad stories about me."

After Pee Wee recovered, he completely changed his life style. He began eating regular meals, with which he drank milk and sometimes a glass of ale, but nothing stronger. He began to relax more and, at the urging of his wife, Mary, tried to diversify his interests.

"I haven't done anything except spend my life with a horn stuck in my face," he told a friend.

He began to turn down jobs that didn't appeal to him musically, staying home much of the time. For a while Mary wasn't sure she knew who he was. She said she had to get used to him all over again.

"He talks a lot now," she told an interviewer. "He never used to. It's as if he were trying to catch up."

After our first sojourn together in Boston, I played with Pee Wee on a couple of jobs with Jimmy McPartland in New York. And, since my apartment in the Village was not far from the building on King Street where Pee Wee and Mary lived, I saw him occasionally around the neighborhood, usually walking his little dog Winky up Seventh Avenue South. We'd stroll along together and chat about this and that while Pee Wee let the dog sniff and mark the tree trunks.

Once in a while Pee Wee would invite me over to the White Horse Tavern for a beer. He'd tell me stories about growing up in Missouri or playing with different bands in Texas or Chicago, but I was never clear about the chronology. I got the impression that he remembered life in the '20s and '30s with much more clarity than he did the '40s.

One summer afternoon I invited Pee Wee to accompany me for a swim at the city pool between Carmine and Leroy streets. He gave me an excruciatingly pained look.

"The world isn't ready for me in swim trunks."

Pee Wee surprised everyone in 1962 when, in collaboration with valve trombonist Marshall Brown, bassist Russell George and drummer Ron Lundberg, he began to use some modern jazz forms. Marshall pushed Pee Wee into learning some John Coltrane tunes and experimenting with musical structures he hadn't tried before. He made the transition with the same fierce effort with which he'd always approached improvisation, and the group made some good records.

Marshall, a so-so soloist who had been a high school music teacher, was tremendously enthusiastic, but was a terrible pedant, though a good-natured one. He couldn't resist taking the role of the instructor, even with accomplished musicians. Pee Wee told an interviewer, "Marshall certainly brought out things in me. It was strange. When he would correct me, I would say to myself, now why did he have to tell me that? I knew that already."

Mary Russell commented, "Pee Wee wants to kill him."

"I haven't taken so many orders since military school," said Pee Wee.

One day Pee Wee told me that he and Mary were moving out of their old apartment. A new development had been built between Eighth and Ninth avenues north of Twenty-third Street where several blocks of old tenements had been torn down. The Russell’s had bought a coop apartment there. Around the same time, Aileen and I moved into an apartment building on the corner of Twentieth Streetand Ninth Avenue, so I was still in Pee Wee's neighborhood. I would bump into him on the street now and then.

In 1965, Mary came home one day with a set of oil paints and some canvases on stretchers. She dumped it all in Pee Wee's lap and said, "Here, do something with yourself. Paint!"

He did. Holding the canvases in his lap or leaning them on the kitchen table as he painted, he produced nearly a hundred paintings during the ensuing two years, in a strikingly personal, primitive style. With bold brush strokes and solid masses of color he created abstract shapes, some with eccentric, asymmetrical faces. They were quite amazing. Though he enjoyed the praise of his friends and was delighted when some of his works sold at prices that astonished him, he painted primarily for Mary's appreciation. When she died in 1967, he put away his brushes for good.

With Mary gone, Pee Wee went back to drinking, and his health began to slowly deteriorate. In February 1969, during a Visit to Washington, D.C., he was feeling so bad that he called a friend and had him check him into AlexandriaHospital. The doctors shut off his booze and did what they could to restore him to health, but this time he failed to respond to treatment. After a few days he just slipped away in his sleep.

The Jerseyjazz Society keeps Pee Wee's memory alive with their annual Pee Wee Russell Memorial Stomp, and there have been occasional showings of his paintings at art galleries. And, of course, there are still the records, reminding us of how wonderfully Pee Wee's playing teetered at the edge of musical disaster, where he struggled mightily, and prevailed.”

Whitney Balliett, American Musicians: 56 Portraits in Jazz [New York: OxfordUniversity Press, 1986, pp. 127-135]

Even His Feet Look Sad

“The clarinetist Pee Wee Russell was born in St. Louis, Missouri, in March of 1906, and died just short of his sixty-third birthday in Arlington, Virginia. He was unique-in his looks, in his inward-straining shyness, in his furtive, circumambulatory speech, and in his extraordinary style. His life was higgledy-piggledy. He once accidentally shot and killed a man when all he was trying to do was keep an eye on a friend's girl. He spent most of his career linked-in fact and fiction-to the wrong musicians. People laughed at him-he looked like a clown perfectly at ease in a clown's body-when, hearing him, they should have wept. He drank so much for so long that he almost died, and when he miraculously recovered, he began drinking again. In the last seven or eight years of his life, he came into focus: his originality began to be appreciated, and he worked and recorded with the sort of musicians he should have been working and recording with all his life. He even took up painting, producing a series of seemingly abstract canvases that were actually accurate chartings of his inner workings. But then, true to form, the bottom fell out. His wife Mary died unexpectedly, and he was soon dead himself. Mary had been his guidon, his ballast, his right hand, his helpmeet. She was a funny, sharp, nervous woman, and she knew she deserved better than Pee Wee. She had no illusions, but she was devoted to him. She laughed when she said this: 'Do you know Pee Wee? I mean what do you think of him? Oh, not those funny sounds that come out of his clarinet. Do you know him? You think he's kind and sensitive and sweet. Well, he's intelligent and he doesn't use dope and he is sensitive, but Pee Wee can also be mean. In fact, Pee Wee is the most egocentric son of a bitch I know."

No jazz musician has ever played with the same daring and nakedness and intuition. His solos didn't always arrive at their original destination. He took wild improvisational chances, and when he found himself above the abyss, he simply turned in another direction, invariably hitting firm ground. His singular tone was never at rest. He had a rich chalumeau register, a piping upper register, and a whining middle register, and when he couldn't think of anything else to do, he growled. Above all, he sounded cranky and querulous, but that was camouflage, for he was the most plaintive and lyrical of players. He was particularly affecting in a medium or slow-tempo blues. He'd start in the chalumeau range with a delicate rush of notes that were intensely multiplied into a single, unbroken phrase that might last the entire chorus. Thus he'd begin with a pattern of winged double-time staccato notes that, moving steadily downward, were abruptly pierced by falsetto jumps. When he had nearly sunk out of hearing, he reversed this pattern, keeping his myriad notes back to back, and then swung into an easy uphill-down dale movement, topping each rise with an oddly placed vibrato.

By this time, his first chorus was over, and one had the impression of having passed through a crowd of jostling, whispering people. Russell then took what appeared to be his first breath, and, momentarily breaking the tension he had established, opened the next chorus with a languorous, questioning phrase made up of three or four notes, at least one of them a spiny dissonance of the sort favored by Thelonious Monk. A closely linked variation would follow, and Russell would fill out the chorus by reaching behind him and producing an ironed paraphrase of the chalumeau first chorus. In his final chorus, he'd move snakily up toward the middle register with tissue-paper notes and placid rests, taking on a legato I've-made-it attack that allowed the listener to move back from the edge of his seat.

Here is Russell in his apartment on King Street, in Greenwich Village, in the early sixties, when he was on the verge of his greatest period. It wasn't a comeback he was about to begin, though, for he'd never been where he was going. Russell lived then on the third floor of a peeling brownstone. He was standing in his door, a pepper-and-salt schnauzer barking and dancing about behind him. "Shut up, Winkie, for God's sake!" Russell said, and made a loose, whirlpool gesture at the dog. A tall, close packed, slightly bent man, Russell had a wry, wandering face, dominated by a generous nose. The general arrangement of his eyes and eyebrows was mansard, and he had a brush mustache and a full chin. A heavy trellis of wrinkles held his features in place. His gray-black hair was combed absolutely flat. Russell smiled, without showing any teeth, and went down a short, bright hall, through a Pullman kitchen, and into a dark living room, brownish in color, with two day beds and two easy chairs, a bureau, a television, and several small tables. The corners of the room were stuffed with suitcases and fat manila envelopes. Under one table were two clarinet cases. The shades on the three windows were drawn, and only one lamp was lit. The room was suffocatingly hot. Russell, who was dressed in a tan, short-sleeved sports shirt, navy-blue trousers, black socks, black square-toed shoes, and dark glasses, sat down in a huge red leather chair. "We've lived in this cave six years too long. Mary's no housekeeper, but she tries. Every time a new cleaning gadget comes out, she buys it and stuffs it in a closet with all the other ones. I bought an apartment three years ago in a development on Eighth Avenue in the Chelsea district, and we're moving in. It has a balcony and a living room and a bedroom and a full kitchen. We'll have to get a cleaning woman to keep it respectable." Russell laughed - a sighing sound that seemed to travel down his nose.

"Mary got me up at seven this morning before she went to work, but I haven't had any breakfast, which is my own fault. I've been on the road four weeks-two at the Theatrical Cafe, in Cleveland, with George Wein, and two in Pittsburgh with Jimmy McPartland. I shouldn't have gone to Pittsburgh. I celebrated my birthday there, and I'm still paying for it, physically and mentally. And the music. I can't go near 'Muskrat Ramble' any more without freezing up. Last fall, I did a television show with McPartland and Eddie Condon and Bud Freeman and Gene Krupa and Joe Sullivan-all the Chicago boys. We made a record past before it. They sent me a copy the other day and I listened halfway through and turned it off and gave it to the super. Mary was here, and she said, 'Pee Wee, you sound like you did when I first knew you in 1942.' I'd gone back twenty years in three hours. There's no room left in that music. It tells you how to solo. You're as good as the company you keep. You go with fast musicians, housebroken musicians, and you improve."

Russell spoke in a low, nasal voice. Sometimes he stuttered, and sometimes whole sentences came out in a sluice-like manner, and trailed off into mumbles and down-the-nose laughs. His face was never still. When he was surprised, he opened his mouth slightly and popped his eyes, rolling them up to the right. When he was thoughtful, he glanced quickly about, tugged his nose, and cocked his head. When he was amused, everything turned down instead of up-the edges of his eyes, his eyebrows, and the corners of his mouth. Russell got up and walked with short, crab-wise steps into the kitchen. "Talking dries me up," he said. "I'm going to have an ale."

There were four framed photographs on the walls. Two of them showed what was already unmistakably Russell, in a dress and long, curly hair. In one, he was sucking his thumb. In the other, an arm was draped about a cocker spaniel. The third showed him at about fifteen, in military uniform, standing beneath a tree, and in the fourth he was wearing a dinner jacket and a wing collar and holding an alto saxophone. Russell came back, a bottle of ale in one hand and a pink plastic cup in the other.

Isn't that something? A wing collar. I was sixteen, and my father bought we that saxophone for three hundred and seventy-five dollars." Russell filled his cup and put the bottle on the floor. "My father was a steward at the Planter's Hotel, in St. Louis, when I was born, and I was named after him - Charles Ellsworth. I was a late child and the only one. My mother was forty. She was a very intelligent person. She'd been a newspaperwoman in Chicago, and she used to read a lot. Being a late child, I was excess baggage. I was like a toy. My parents, who were pretty well off, would say, You want this or that, it's yours. But I never really knew them. Not that they were cold, but they just didn't divulge anything. Someone discovered a few years ago that my father had a lot of brothers. I never knew he had any. When I was little, we moved to Muskogee, where my father and a friend hit a couple of gas wells. I took up piano and drums and violin, roughly in that order. One day, after I'd played in a school recital, I put my violin in the back seat of our car and my mother got in and sat on it. That was the end of my violin career. 'Thank God that's over,' I said to myself.

I tried the clarinet when I was about twelve or thirteen. I studied with

Charlie Merrill, who was in the pit band in the only theatre in Muskogee. Oklahomawas a dry state and he sneaked corn liquor during the lessons. My first job was playing at a resort lake. I played for about twelve hours and made three dollars. Once in a while, my father'd take me into the Elks' Club, where I heard Yellow Nunez, the New Orleansclarinet player. He had a trombone and piano and drums with him, and he played the lead in the ensembles. On my next job, I played the lead, using the violin part. Of course, I'd already heard the Original Dixieland Jazz Band on records. I was anxious in school-anxious to finish it. I'd drive my father to work in his car and, instead of going on to school, pick up a friend and drive around all day. I wanted to study music at the University of Oklahoma, but my aunt-she was living with us-said I was bad and wicked and persuaded my parents to take me out of high school and send me to Western Military Academy, in Alton, Illinois. My aunt is still alive. Mary keeps in touch with her, but I won't speak to her. I majored in wigwams at the military school, and I lasted just a year. Charlie Smith, the jazz historian, wrote the school not long ago and they told him Thomas Hart Benton and I are their two most distinguished non-graduates." Russell laughed and poured out more ale.

"We moved back to St. Louis and I began working in Herbert Berger's hotel band. It was Berger who gave me my nickname. Then I went with a tent show to Moulton, Iowa. Berger had gone to Juarez, Mexico, and he sent me a telegram asking me to join him. That was around the time my father gave me the saxophone. I was a punk kid, but my parents-can you imagine? - said, Go ahead, good riddance. When I got to Juarez, Berger told me, to my surprise, I wouldn't be working with him but across the street with piano and drums in the Big Kid's Palace, which had a bar about a block long. There weren't any microphones and you had to blow. I must have used a board for a reed. Three days later there were union troubles and I got fired and joined Berger. This wasn't long after Pancho Villa, and all the Mexicans wore guns. There'd be shooting in the streets day and night, but nobody paid any attention. You'd just duck into a saloon and wait till it was over. The day Berger hired me, he gave me a ten-dollar advance. That was a lot of money and I went crazy on it. It was the custom in Juarezto hire a kind of cop at night for a dollar, and if you got in a scrape he'd clop the other guy with his billy. So I hired one and got drunk and we went to see a bulldog-badger fight, which is the most vicious thing you can imagine. I kept on drinking and finally told the cop to beat it, that I knew the way back to the hotel in El Paso, across the river. Or I thought I did, because I got lost and had an argument over a tab and the next thing I was in jail. What a place, Mister! A big room with bars all the way around and bars for a ceiling and a floor like a cesspool, and full of the worst cutthroats you ever saw. I was there three days on bread and water before Berger found me and paid ten dollars to get me out." Russell's voice trailed off. He squinted at the bottle, which was empty, and stood up. "I need some lunch."

The light outside was blinding, and Russell headed west on King Street, turned up Varick Street and into West Houston. He pointed at a small restaurant with a pine-paneled front, called the Lodge. "Mary and I eat here sometimes evenings. The food's all right." He found a table in the back room, which was decorated with more paneling and a small pair of antlers. A waiter came up. "Where you been, Pee Wee? You look fifteen years younger." Russell mumbled a denial and something about his birthday and Pittsburgh and ordered a Scotch-on-the-rocks and ravioli. He sipped his drink for a while in silence, studying the tablecloth. Then he looked up and said, "For ten years I couldn't eat anything. All during the forties. I'd be hungry and take a couple of bites of delicious steak, say, and have to put the fork down-finished. My food wouldn't go from my upper stomach to my lower stomach. I lived on brandy milkshakes and scrambled-egg sandwiches. And on whiskey. The doctors couldn't find a thing. No tumors, no ulcers. I got as thin as a lamppost and so weak I had to drink half a pint of whiskey in the morning before I could get out of bed. It began to affect my mind, and sometime in 1948 I left Mary and went to Chicago. Everything there is a blank, except what people have told me since. They say I did things that were unheard of, they were so wild. Early in 1950, I went on to San Francisco. By this time my stomach was bloated and I was so feeble I remember someone pushing me up Bush Street and me stopping to put my arms around each telegraph pole to rest. I guess I was dying. Some friends finally got me into the FranklinHospital and they discovered I had pancreatitis and multiple cysts on my liver. The pancreatitis was why I couldn't eat for so many years. They operated, and I was in that hospital for nine months. People gave benefits around the country to pay the bills. I was still crazy. I told them Mary was after me for money. Hell, she was back in New York, minding her own business. When they sent me back here, they put me in St. Clare's Hospital under an assumed name-McGrath, I think it was-so Mary couldn't find me. After they let me out, I stayed with Eddie Condon. Mary heard where I was and came over and we went out and sat in Washington Square park. Then she took me home. After three years."

Russell picked up a spoon and twiddled the ends of his long, beautifully tapered fingers on it, as if it were a clarinet. "You take each solo like it was the last one you were going to play in your life. What notes to hit, and when to hit them-that's the secret. You can make a particular phrase with rust one note. Maybe at the end, maybe at the beginning. It's like a little pattern. What will lead in quietly and not be too emphatic. Sometimes I jump the right chord and use what seems wrong to the next guy but I know is right for me. I usually think about four bars ahead what I am going to play. Sometimes things go wrong, and I have to scramble. If I can make it to the bridge of the tune, I know everything will be all right. I suppose it's not that obnoxious the average musician would notice. When I play the blues, mood, frame of mind, enters into it. One day your choice of notes would be melancholy, a blue trend, a drift of blue notes. The next day your choice of notes would be more cheerful. Standard tunes are different. Some of them require a legato treatment, and others have sparks of rhythm you have to bring out. In lots of cases, your solo depends on who you're following. The guy played a great chorus, you say to yourself. How am I going to follow that? I applaud him inwardly, and it becomes a matter of silent pride. Not jealousy, mind you. A kind of competition. So I make myself a guinea pig-what the hell, I’ll try something new. All this goes through your mind in a split second. You start and if it sounds good to you, you keep it up and write a little tune of your own. I get in bad habits and I'm trying to break myself of a couple right now. A little triplet thing, for one. Fast tempos are good to display your technique, but that's all. You prove you know the chords, but you don't have the time to insert those new little chords you could at slower tempos. Or if you do, they go unnoticed. I haven't been able to play the way I want to until recently.

Coming out of that illness has given me courage, a little moral courage in my playing. When I was sick, I lived night by night. It was bang! straight ahead with the whiskey. As a result, my playing was a series of desperations. Now I have a freedom. For the past five or so months, Marshall Brown, the trombonist, and I have been rehearsing a quartet in his studio - just Brown, on the bass cornet, which is like a valve trombone; me, a bass, and drums. We get together a couple of days a week and we work. I didn't realize what we had until I listened to the tapes we've made. We sound like seven or eight men. Something's always going. There's a lot of bottom in the group. And we can do anything we want soft, crescendo, decrescendo, textures, voicings. What musical knowledge we have, we use it. A little while ago, an a. & r. man from one of the New York jazz labels approached me and suggested a record date-on his terms. Instead, I took him to Brown's studio to hear the tapes. He was cool at first, but by the third number he looked different. I scared him with a stiff price, so well see what happens. A record with the quartet would feel just right. And no 'Muskrat Ramble' and no 'RoyalGarden Blues."'

Outside the Lodge, the sunlight seemed to accelerate Russell, and he got back to King Street quickly. He unlocked the door, and Winkie barked. "Cut that out, Winkie!" Russell shouted. "Mary'll be here soon and take you out." He removed his jacket, folded it carefully on one of the day beds, and sat down in the red chair with a grunt.

"I wish Mary was here. She knows more about me than III ever know. Well, after Juarez I went with Berger to the Coast and back to St. Louis, where I made my first record, in 1923 or 1924. 'Fuzzy Wuzzy Bird,' by Herbert Berger and his Coronado Hotel Orchestra. The bad notes in the reed passages are me. I also worked on the big riverboats - the J. S., the St. Paul - during the day and then stayed at night to listen to the good bands, the Negro bands like Fate Marable's and Charlie Creath's. Then Sonny Lee, the trombonist, asked me did I want to go to Houston and play in Peck Kelley's group. Peck Kelley's Bad Boys. At this time, spats and a derby were the vogue, and that's what I was wearing when I got there.

Kelley looked at me in the station and didn't say a word. We got in a cab and I could feel him still looking at me, so I rolled down the window and threw the derby out. Kelley laughed and thanked me. He took me straight to Goggan's music store and sat down at a piano and started to play. He was marvelous, a kind of stride pianist, and I got panicky. About ten minutes later, a guy walked in, took a trombone off the wall, and started to play. It was Jack Teagarden. I went over to Peck when they finished and said, 'Peck, I'm in over my head. Let me work a week and make my fare home.' But I got over it and I was with Kelley several months." Russell went into the kitchen to get another bottle of ale. "Not long after I got back to St. Louis, Sonny Lee brought Bix Beiderbecke around to my house, and bang! we hit it right off. We were never apart for a couple of years-day, night, good, bad, sick, well, broke, drunk.

Then Bix left to join Jean Goldkette's band and Red Nichols sent for me to come to New York. That was 1927. I went straight to the old Manger Hotel and found a note in my box: Come to a speakeasy under the Roseland Ballroom. I went over and there was Red Nichols and Eddie Lang and Miff Mole and Vic Berton. I got panicky again. They told me there'd be a recording date at Brunswick the next morning at nine, and don't be late. I got there at eight-fifteen. The place was empty, except for a handyman. Mole arrived first. He said, 'You look peaked, kid,' and opened his trombone case and took out a quart. Everybody had quarts. We made 'lda,' and it wasn't any trouble at all. In the late twenties and early thirties I worked in a lot of bands and made God knows how many records in New York. Cass Hagen, Bert Lown, Paul Specht, Ray Levy, the Scranton Sirens, Red Nichols. We lived uptown at night. We heard Elmer Snowden and Luis Russell and Ellington. Once I went to a ballroom where Fletcher Henderson was. Coleman Hawkins had a bad cold and I sat in for him one set. My God, those scores! They were written in six flats, eight flats, I don't know how many flats. I never saw anything like it. Buster Bailey was in the section next to me, and after a couple of numbers I told him, 'Man, I came up here to have a good time, not to work. I've had enough. Where's Hawkins?'

"I joined Louis Prima around 1935. We were at the Famous Door, on Fifty-second Street, and a couple of hoodlums loaded with knives cornered Prima and me and said they wanted protection money every week fifty bucks from Prima and twenty-five from me. Well, I didn't want any of that. I'd played a couple of private parties for Lucky Luciano, so I called him. He sent Pretty Amberg over in a big car with a bodyguard as chauffeur. Prima sat in the back with Amberg and I sat in front with the bodyguard. Nobody said much, just 'Hello' and 'Goodbye,' and for a week they drove Prima and me from our hotels to a midday radio broadcast, back to our hotels, picked us up for work at night, and took us home after.

We never saw the protection-money boys again. Red McKenzie, the singer, got me into Nick's in 1938, and I worked there and at Condon's for most of the next ten years. I have a sorrow about that time. Those guys made a joke of me, a clown, and I let myself be treated that way because I was afraid. I didn't know where else to go, where to take refuge. I'm not sure how all of us feel about each other now, though we're 'Hello, Pee Wee,''Hello, Eddie,' and all that. Since my sickness, Mary's given me confidence, and so has George Wein. I've worked for him with a lot of fast musicians in Boston, in New York, at Newport, on the road, and in Europelast year. III head a kind of house band if he opens a club here. A quiet little group. But Nick's did one thing. That's where I first met Mary."

At that moment, a key turned in the lock, and Mary Russell walked quickly down the hall and into the living room. A trim, pretty, black-haired woman in her forties, she was wearing a green silk dress and black harlequin glasses.

"How's Winkie been?" she asked Russell, plumping herself down and taking off her shoes. "She's the kind of dog that's always barking except at burglars. Pee Wee, you forgot to say, Did you have a hard day at the office, dear? And where's my tea?"

Russell got up and shuffled into the kitchen.

"I work in the statistics and advertising part of Robert Hall clothes," she said. "I've got a quick mind for figures. I like the job and the place. It's full of respectable ladies. Pee Wee, did I get any mail?"

"Next to you, on the table. A letter," he said from the kitchen.

"It's from my brother Al," she said. "I always look for a check in letters. My God, there is a check! Now why do you suppose he did that? And there's a P.S.: Please excuse the pencil. I like that. It makes me feel good."

"How much did he send you?" Russell asked, handing Mrs. Russell her tea.

"You're not going to get a cent," she said. "You know what I found the other day, Pee Wee? Old letters from you. Love letters. Every one says the same thing: I love you, I miss you. just the dates are different." Mary Russell, who spoke in a quick, decisive way, laughed. "Pee Wee and I had an awful wedding. It was at City Hall. Danny Alvin, the drummer, stood up for us. He and Pee Wee wept. I didn't, but they did. After the ceremony, Danny tried to borrow money from me. Pee Wee didn't buy me any flowers and a friend lent us the wedding ring. Pee Wee has never given me a wedding ring. The one I'm wearing a nephew gave me a year ago. Just to make it proper, he said. That's not the way a woman wants to get married. Pee Wee, we ought to do it all over again. I have a rage in me to be proper. I don't play bridge and go to beauty parlors and I don't have women friends like other women. But one thing Pee Wee and I have that no one else has: we never stop talking when we're with each other. Pee Wee, you know why I love you? You're like Papa. Every time Mama got up to tidy something, he'd say, Clara, sit down, and she would. That's what you do. I loved my parents. They were Russian Jews from Odessa. Chaloff was their name. I was born on the lower East Side. I was a charity case and the doctor gave me my name, and signed the birth certificate - Dr. E. Condon. Isn't that weird? I was one of nine kids and six are left. I've got twenty nephews and nieces." Mary Russell paused and sipped her tea.

"Pee Wee worships those inch brows. Lucky Luciano was his dream man.”

"He was an acquaintance," Russell snorted.

"I’ll never know you completely, Pee Wee," Mrs. Russell said. She took another sip of tea, holding the cup with both hands. "Sometimes Pee Wee can't sleep. He sits in the kitchen and plays solitaire, and I go to bed in here and sing to him. Awful songs like 'Belgian Rose' and 'Carolina Mammy.' I have a terrible voice."

"Oh, God!" Russell muttered. "The worst thing is she knows all the lyrics."

"I not only sing, I write," she said, laughing. "I wrote a three-act play. My hero's name is Tiny Ballard. An Italian clarinet player. It has wonderful dialogue."

"Mary's no saloon girl, coming where I work," he said. "She outgrew that long ago. She reads about ten books a week. You could have been a writer, Mary."

"I don't know why I wrote about a clarinet player. I hate the clarinet. Pee Wee's playing embarrasses me. But I like trombones: Miff Mole and Brad Gowans. And I like Duke Ellington. Last New Year's Eve, Pee Wee and I were at a party and Duke kissed me at midnight."

"Where was l?" he asked.

"You had a clarinet stuck in your mouth," she said. "The story of your life, or part of your life. Once when Pee Wee had left me and was in Chicago, he came back to New York for a couple of days. He denies it. He doesn't remember it. He went to the night club where I was working as a hat-check girl and asked to see me. I said no. The boss's wife went out and took one look at him and came back and said, 'At least go out and talk to him. He's pathetic. Even his feet look sad."'

Russell made an apologetic face. "That was twelve years ago, Mary. I have no claim to being an angel."

She sat up very straight. "Pee Wee, this room is hot. Let's go out and have dinner on my brother Al."

"I'll put on a tie," he said.”

Pee Wee Russell: Part 2

© - Steven A. Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“[With] Russell’s music … there’s a danger in patronizing his home-made approach to playing and he was inconsistent, but his best music is exceptional.” – Richard Cook & Brian Morton, The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD, Sixth Edition.

“Pee Wee Russell’s ballad playing is one of the glories of Jazz. Gary Giddins, Visions of Jazz. [paraphrase]

At first hearing, a Pee Wee Russell solo tended to give the impression of a somewhat inept musician, awkward and shy, stumbling and muttering along in a rather directionless fashion. Upon close inspection, such peculiarities – the unorthodox tone, the halting continuity, the odd choice of notes – are manifestations of a unique, wondrously self-contained musical personality, which operated almost entirely on its own artistic laws.” Gunter Schuller, The Swing Era: The Development of Jazz, 1930-1945. [paraphrase]

“Some have suggested that Russell’s eccentric style of improvisation defies description. Not true. … Yet, whether his music is viewed as a Delphic utterance laden with secret meanings, an expression of eccentricity, or simply a style built around various limitations, Russell ultimately succeeded where it counted most: in attracting a devoted following, one that lived vicariously through his embrace of the unorthodox. For those fans who became part of the cult of Pee Wee, there was no other clarinetist half so grand.” Ted Gioia, The History of Jazz.

Richard Sudhalter, in his Lost Chords: White Musicians and Their Contribution to Jazz, 1915 – 1945 [New York: Oxford, 1999] offers a number of excellent observations about the evolution of Pee Wee’s style.

One point Sudhalter stresses about Pee Wee’s approach to Jazz was that he had a tremendous affinity for the blues. And yet, ironically, “if there is any single figure that helped shape Russell’s musical outlook directly in those early years it was Bix Beiderbecke, a musician clearly without much noticeable affinity for the blues.” [p. 711]

“Russell clearly found something compelling in Bix, a set of governing aesthetic principles that stayed with him, and in later years he called the short-lived cornetist ‘one of the greatest musicians who ever lived. He had more imagination and more thought than anybody else I can think of … Everything he played I loved.’” [p. 712]

In his early years, Pee Wee’s style was also compared to another of his short-lived compatriots, clarinetist Frank Teschemacher. Sudhalter’s opinion of this comparison is

“To be sure, both men phrased in an angular manner favoring a gritty, ‘non-legit’ tone and technique … and used pitch in unconventional ways. But recorded evidence suggests that any similarities between them is no more than a nexus, an intersection of two individual trajectories.

By the time of Teschemacher’s death in 1932, …. records made between 1928 and 1932 …. Show more polished technique, introduction of a liquid, almost Jimmy Noone-like tone, increased regularity of phrasing, more ‘Conventional’ pitch sense.

Russell, by contrast, seems in the same years to be moving in the opposite direction. Where his sound and approach on his first records are balanced, even Bix-like, in their symmetry and sense of order, he very soon began a process of what can almost be termed deconstruction.

His work on records from 1928 on, in fact, conveys the sense that he is systematically dismantling that sense of order, then reassembling the pieces according to some new inner imperative.”[p. 712; paragraphing modified; emphasis mine].

To paraphrase Sudhalter, it would seem that the evolution of Pee Wee’s style of clarinet playing went through a number of metamorphoses ranging from one of capturing the inner spirit of Bix with his clear tone and poised phrasing to a later vocabulary that included a wide range of squawks and growls, cries and whispers. [p. 713]

What we also see evolving in his style over the years is more assertiveness and individualism or as Sudhalter describes it:

“punching, trumpet-like attacks alternating with sotto voce mutterings; raps and growls; lightning shifts of dynamics and tonal texture; a rubber-band stretching of pitch and rhythmic emphasis; and, perhaps above all; a keening quality rare in hot solo work of the time [c. 1925-1935], white or black, as different from the majesty of Bechet and Armstrong as from the thoughtful symmetry of Beiderbecke.” [p. 717]

Pee Wee Russell: Jazz Original [Commodore CMD-404] contains, according to clarinetist Joe Muranyi, recordings that represent “ … a creative high point in of Pee Wee’s middle years. Muranyi continues, in his excellent insert notes, to offer a number of compelling reasons why he holds this opinion of these Commodore recordings.

In the jazz world he was popular and well-known - in 1942, '43 and '44 he'd even won the Down Beat poll as best clarinetist. Quite an achievement for a guy some considered a drunken clown. He had a lifelong battle with the bottle, that's for sure, and so did many of the guys he ran with - Eddie Condon and his "Barefoot Mob," the barrelhouse crowd that appears on these records. Pee Wee wasn't musically defeated by alcohol. In some strange way, he might have used it. Sober, he was a good musician, musically schooled. Early on, he read well enough to work in saxophone sections. But he was a quiet, shy person, and possibly drinking dulled his inhibitions and freed him to create. In any case, something drove him into unusual musical channels, where his ear and his own feelings were his only guide.

Luckily, Pee Wee was a natural and it all worked out. But the eccentric aspects of his style are often explained away by saying that he drank too much. I know that’s wrong, that the truth is that Pee Wee’s music speaks for itself – and yes, he did drink.

Teagarden, Bobby Hackett, Bud Freeman, and Russell form a musical ‘murderer's row’ of soloists on several numbers here recorded under the nominal leadership of Eddie Condon. Their collaborations are not at all dated; the background arrangements (uncredited, but very possibly by Hackett) are subtle and the recording balance is particularly helpful to Pee Wee. His two spike-y choruses on “Love Is Just Around the Corner’ place him in front of the band in a sort of loose ensemble/solo mode that's just right, and his half chorus on ‘Embraceable You’ still lives!

Pee Wee's explorative mind is documented on two differently detailed versions of a traditional style blues, ‘Serenade to a Shylock’ (that was the now-forgotten slang term for the pawnbroker in whose shop many instruments spent much of their time). The clarinet accompaniments behind Jack's vocals are quite dissimilar, and Take 2 boldly uses the major seventh and flat five - notes that would first be used this way in modern jazz around 1941, and this is 1938!

Later in Pee Wee's life it become an axiom that he had been ill-served by Dixieland and the Condon crowd. Well, I don't think so. The music on this CD can serve as a good definition of Dixieland. A rousing, collectively improvised ensemble is a perennial source of joy, and Charlie was the best of clarinetists for that. As in all jazz, the style is as good as the practitioners, and our man was among the greatest Dixieland players - as well as being more, lots more. Without giving a single thought to it, he had a foot in both worlds, although he never lost his Dixieland feel. He had already been a ‘modern’ stylist in the Twenties, and had he stayed with Condon-type groups all his life (as in a way he did), he would have ended up with the some degree of recognition - for he brought his modernism to his Dixieland work.

The trio and quartet sessions feature Russell's magnificent blues playing. The date with Joe Sullivan and Zutty Singleton harkens back stylistically to the Twenties. “The Last Time I Saw Chicago” is a delicious blues and when Pee Wee plays in the low register, with Zutty press-rolling and Joe tremoloing a la Earl Hines, all is righteous! Among the later quartet sides we find three versions of something basically titled ‘D. A. Blues’ (although the last take earns a slightly different title, presumably because of its different tempo) that bring everything to an appropriate close. Pee Wee's chalumeau choruses after Jess Stacy's piano solos are hair-raising journeys into a surrealistic subterranean world of the blues. By the third try, Russell has really wormed to his task and starts with a remarkable chromatic phrase, using the flat and major seventh, the ninth, the sixth and the augmented fifth intervals([!). Quite melodic, it swings, too. It's in his full-bloom sotto voce mode. He even plays games with the phrase that was to become his "Pee Wee's Blues." On other tracks in this compilation, if you pay close attention, you can hear him use this sequence in many ways.

… Russell was a master of mood … and was most effective on slow ballards and blues, using a sub-tone that tapped a deep emotional wellspring. It was his greatest achievement, quite a contribution to the voice of jazz clarinet.

We’re in another world with him, a kind of slow-moon minimalist universe. It’s akin to a particularly forceful speaker who lowers his voiced to a hushed tone so he can whisper his story even more effectively.

Pee Wee Russell was an innovator, and an appreciation of his rugged individuality … is an acquired taste. He doesn’t just blow the horn and express himself with conventional good notes and tone. No, he often chooses to use the tone itself as a means of expression: he’ll growl, squeal or drop down into a croaking, spooky, sewer-pipe lower register; or he’ll hum one note while blowing another, resulting in a third note with an unholy life of its own – and another kind of growl. …

His choice of notes and rhythm could be quite unconventional. His red (and blue) notes mostly resolve nicely and, if analyzed, can be explained as the upper notes of a chord – as in bebop. But sometimes he misses and gets involved with a glaring red note; such a moment to me is part of his charm. Man this barrelhouse cat takes chances.

Pee Wee was a great ear player and he was always seeking. In essence, the search was his style.”

According to Mr. Sudhalter, “Pee Wee’s later career was a time of fulfillment and exploration, and for many fans and critics, rediscovery: enough so to almost warrant a chapter of its own.… Reluctant to spend the rest of his days in the lockstep of ‘That’s a Plenty’ and ‘RoyalGardenBlues,’ the clarinetist reached into new areas – new repertoire and, in many cases, new musical companions. …

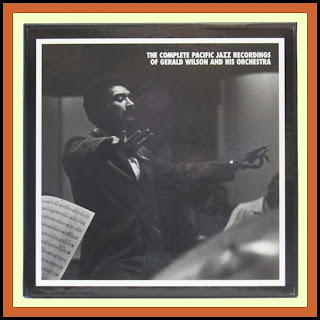

Suddenly it seemed, Pee Wee Russell was the man of the hour, who had always been ‘modern.’ For the 1957 TV show ‘The Sound of Jazz,’ he played the blues in duo with Jimmy Giuffre, whose low-register clarinet style owed much to Russell but lacked its unpredictability and complexity. He recorded such numbers as Billy Strayhorn’s ‘Chelsea Bridge,” John Coltrane’s “Red Planet,’ and the old bop standard ‘Good Bait’ … in a quartet with arranger and valve trombonist Marshall Brown [New Groove: The Pee Wee Russell Quartet , Columbia LP CL 1985; CS 8785].

The new Pee Wee mania reached its peak in 1963, when jazz impresario George Wein paired the clarinetist with Thelonious Monk at the Newport Jazz Festival … and at one concert he played a clarinet duet with Gerry Mulligan who afterwards commented that Russell ‘was inclined to be further out – harmonically and melodically than I am … He was fearless, I never thought of him [strictly] as a clarinet player – it was more like a direct line to his subconscious.’ [emphasis mine].

Let’s conclude this excursion into Pee Wee Russell’s “Land of Jazz” – one that we earlier described as singular, scintillating and shuddery – with the following summary from Richard Sudhalter [paraphrased]:

“Admiration of Russell’s work centered on three qualities: his highly expressive and frequently un-clarinet-like tone; his free and defiant rhythmic sense and, perhaps, above all, his ceaseless daring. His playing was immediate, warm, musically intelligent and naturally swinging.

His inimitable ways represent the highest form of creativity available to a jazz improviser. Far from being ‘eccentric,’ ‘maverick’ or ‘idiosyncratic,’ Pee Wee belongs at the very center of stylistic distinction.

Perhaps the ultimate tribute is to try and imagine Jazz without him.”

You can checkout Pee Wee's distinctive style of clarinet playing as well as Ron Lundberg's exquisite brush work on the following video montage which is set to Moten Swing and which also features Marshall Brown on valve trombone and Russell George on bass.