© - Steven A. Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

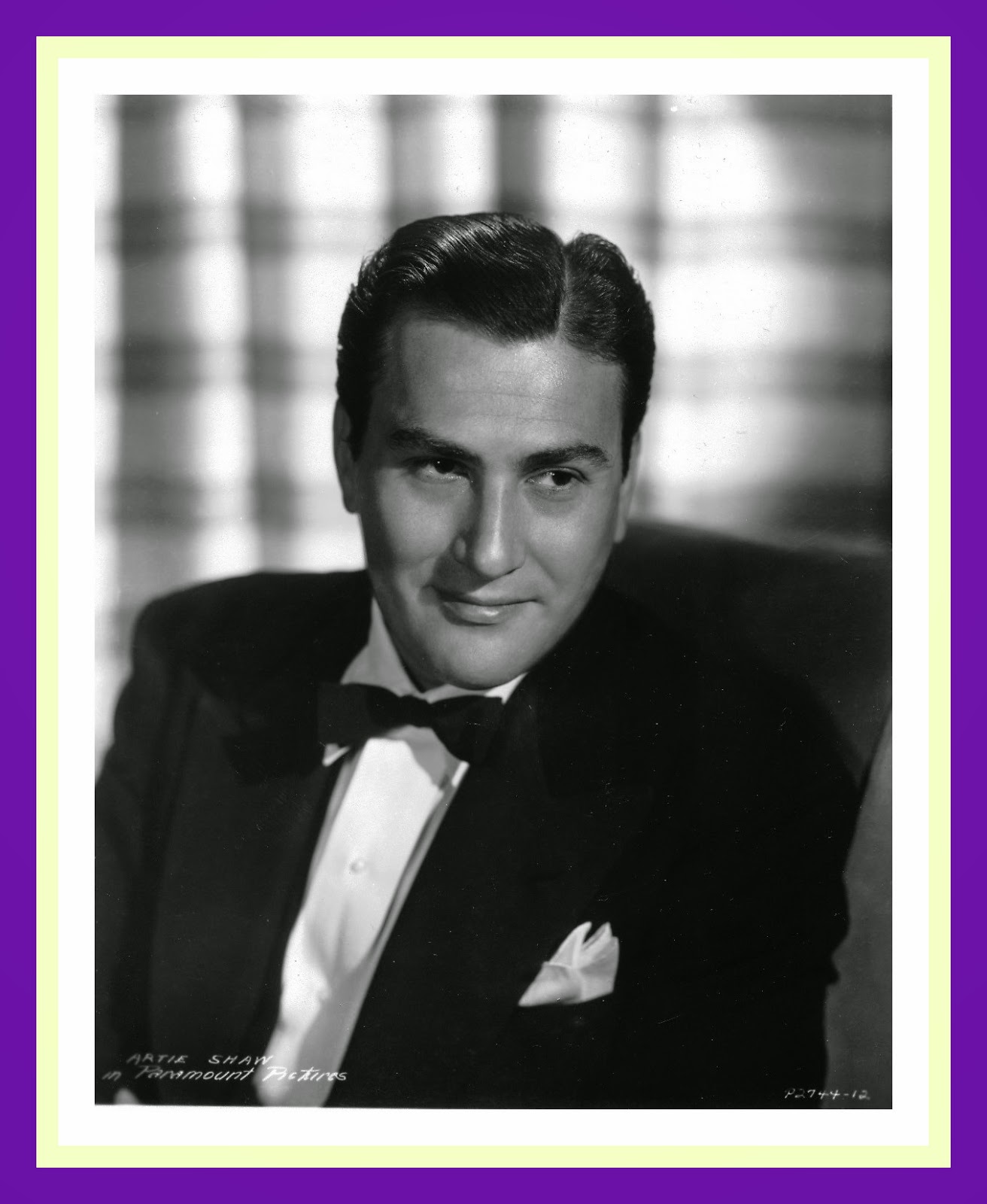

“In the late fall of 1939,... clarinetist Artie Shaw stormed off the bandstand, abandoning the money-making machine it had taken him years to build up. Shaw claimed he was fed up with the dehumanizing pressures of show business and commercial music, and that he would never play again. To most observers in that late-Depression year, it seemed as if Shaw was tossing a monkey wrench in the works of the American dream: to be willing to throw away hundreds of thousands of dollars in pursuit of what was then an obscure concept called artistic integrity.”

- Will Friedwald, Sinatra: The Song is You, p. 163

“Despite his [Artie Shaw’s] affectations of reclusiveness, he never tired of talking about himself, as countless long interviews reveal. I do not recall an anecdote he ever told me that was not in some way intended to convey a sense of his own superiority to everyone. …. One wonders how a person of his character could produce such beauty.”

- Gene Lees, Jazz writer

Given the vastness of California and the current volume of traffic on its freeway system, it would be a stretch to call Gene Lees and Artie Shaw “neighbors,” but in a sense, they were.

Both resided west of downtown Los Angeles and relatively near Ventura, CA: Gene lived northeast of that coastal city in Ojai, CA and Artie lived south/southeast of it in the Conejo Valley suburb of Newbury Park.

Getting together for frequent chats was made far easier because they didn’t have to slog through the mess that is Los Angeles proper.

And get together they did as is exemplified by the excerpts from their long talks that Gene collected and annotated in a three part feature entitled The Anchorite which he published in his Jazzletter, June-August 2004.

Strictly speaking and anchorite is a religious recluse… a deep believer...one who won’t sacrifice their moral and ethical principles for crass, commercial benefit.

However, when referring to Artie Shaw, it would appear that Gene ascribes another meaning to the term “anchorite:” a self-serving, egotist whose every motive and action were in support of whatever Artie Shaw wanted, whenever he wanted it.

What comes across in Gene’s detailed look at Artie is a portrait of a supremely talented musician who probably was the greatest Jazz clarinetist who ever lived [apologies to Buddy DeFranco], but who as a person was more-than-likely someone whom most of us would rather stay away from [to put it nicely].

In Gene’s profile, although Artie describes his reclusiveness as self-imposed, one can’t help wondering if he was forced into exile due to a personality that was reprehensible in the extreme because of its nastiness when it actually encountered other human beings.

However, as you will read in parts 2 and parts 3, Artie had deep-seated rationales for the way he felt about things and his arguments against debasing art and oneself by giving the public what it wants at grave cost to one's own beliefs and standards certainly must be given consideration.

It is a fair point-of-view.

But with Artie, all-too-often it is a case of not what he says but the way in which he says it.

Hang on, Gene's travels with Artie is one, wild ride.

The Anchorite: Part One

“Whenever a major public figure dies, someone is bound to write, "An era ended today when ... ." Sometimes it's true, sometimes it isn't.

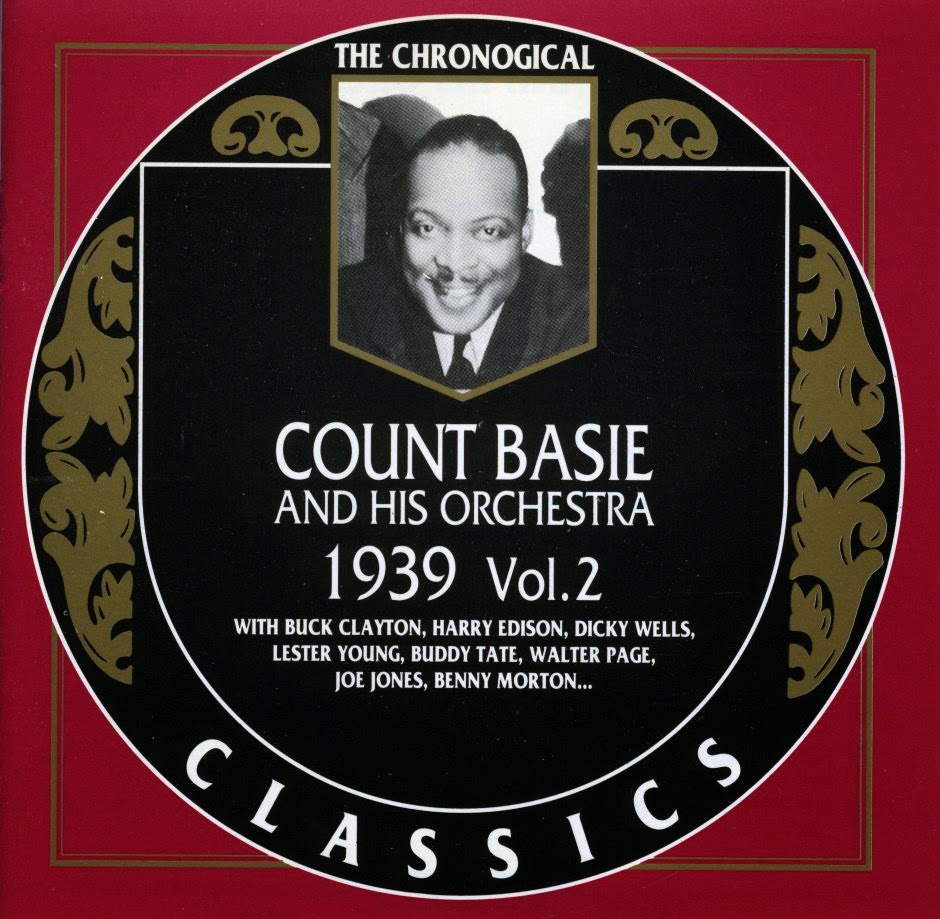

When Artie Shaw died on December 30, 2004, it was. Of the major big band leaders of the so-called swing era, the "jazz" bands with good arrangements and soloists, he was the last one left. Duke Ellington, Tommy Dorsey, Jimmy Dorsey, Glen Gray, Count Basie, Harry James, Benny Goodman, Woody Herman, Stan Kenton, Jimmie Lunceford, Charlie Barnet, Alvino Rey, Les Brown, Lionel Hampton, Gene Krupa were gone, along with the leaders of the "sweet" bands, such as Kay Kyser, Sammy Kaye, Shep Fields, Freddie Martin, Tommy Tucker, Guy Lombardo, and, somewhere between the two, Glenn Miller. Try a survey: ask around among your friends, those who are not musicians, and see how many of them recognize these names. They "were all spirits and are melted into air, into thin air."

When you are young, in any generation, major public names surround you like great trees. When you grow older, and start losing friends, one day you realize that you don't have many left. And then there is another dark revelation: even those famous figures are going, and one day it comes to you: They're clear-cutting the landscape of your life.

Artie Shaw was as famous for quitting the music business and he was for the number of his wives. He did it repeatedly, breaking up and dispersing fine and successful bands. He loathed the music business, in which of course he was hardly alone. A woman wrote that he had had his clarinet made into a lamp. This was an indication of his contempt for her, or for the press in general, because he had too much respect for good instruments (and good musicians) to commit such a desecration. He showed me a couple of his clarinets at his home in Newbury Park, California, where he had lived since 1978. One day he told me on the phone that he'd sent them out for cleaning and maintenance. I hoped that he was thinking of playing again. No. Then why send them out? "Good instruments shouldn't be neglected," he said. In fact, he donated his clarinets, including the Selmer on which he recorded Begin the Beguine to the Smithsonian Institute. That tells us more of what he considered to be his place in history more than anything he ever said.

"I never really considered myself part of the entertainment business," he told me. "I recognized that people had put me in that business. That's where I worked. That is, the ambience I played in had to do with entertainment. So I had to make the concession of having a singer with my band. But that's the only concession I ever made — aside from occasionally playing so-called popular tunes. Mostly I was doing this to meet some inner standard of what I thought a band or I should sound like."

His faith in his own judgment was at least part of the cause of his reputation for arrogance. Arrogance is requisite to the creation of any kind of art. The fact of assuming that what you have to say will be of interest to enough people that you will be able to make a living from it is implicitly arrogant. "As a matter of fact," Artie said, "the arrogance goes so far that you don't care whether it's of interest."

"The only thing," I said, "that humbles the real artist is the art itself."

"That," Artie said, "and his own fallibility."

His favorite singer was Helen Forrest. When she came to him to audition, he asked her, "Are you any good?"

She hesitated. He said, "Well if you don't think you're good, why should I?" She said she was, he listened to her, and he hired her.

Despite his "concession" of having a singer with the band (at one time Billie Holiday), all his hits were instrumentals — Begin the Beguine, Stardust, Frenesi. By 1965 his top five records had sold 65,000,000. For years, RCA paid him not to re-record any of those hits. Beguine, recorded in 1938, was intended as the B side of Indian Love Call.

But his success was not just a commercial success. He was an artist, and after his death, the superlatives flowed. Buddy de Franco said that Shaw's solo on Stardust was the greatest clarinet solo ever recorded. Another clarinetist, Dick Johnson, who fronted an Artie Shaw ghost band in the late years, said at Shaw's funeral service, "I believe he was the greatest jazz clarinetist of all time and one of the very few geniuses I've rubbed elbows with." I've heard one saxophonist and clarinetist after another say that it was Shaw who drew them into becoming a musician.

The late Jerome Richardson, himself a fine saxophonist, clarinetist, and flutist, said, "I was a Benny Goodman fan until I heard Artie Shaw, and that was it. He went to places on the clarinet that no one had ever been before. He would get up to B's and C's and make not notes but music, melodies. He must have worked out his own fingerings for the high notes, because they weren't in the books. To draw a rough analogy, Artie Shaw was at that time to clarinetists what Art Tatum was to pianists. It was another view of clarinet playing. A lot of people loved Benny Goodman because it was within the scope of what most clarinet players could play and therefore could copy. But Artie Shaw took the instrument further."

The late Barney Bigard said, "To me the greatest player that ever lived was Artie Shaw. Benny Goodman played pop songs; he didn't produce new things like Shaw did." Saxophonist Billy Mitchell said, "I'll bet I can still play his clarinet solo on Stardust. I ought to. I spent weeks learning it when I was a kid." For most jazz musicians, and countless layman, that solo is part of the collective memory.

Writer Jon McAuliffe said, "Shaw's shading, tone, and phrasing were singular, and unlike any other, before or since. Listening to Shaw, one can imagine that one is hearing not an instrument so much as an alien human voice. No clarinet player has ever created such an aura of command on the instrument."

Shaw's elegant smooth glissandi always amazed me. One day I asked him how he'd done them.

"I don't know," he replied.

"You must know," I said. "You did them. Is it a matter of squeezing the reed or what?"

"I truly don't know. You think it, and if you know what you're doing, the instrument does it."

Early in 1983, Yoel Levi, conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra, decided to perform Shaw's Concerto for Clarinet with Franklin Cohen, the orchestra's principal clarinetist, performing Shaw's part. Shaw's improvised solo had been transcribed from the record. "When I got the music," Cohen said during rehearsals, "I thought it looked easy. After I heard the tape, I told Yoel he was crazy."

"Shaw was unbelievable," Yoel Levi added. "He was an amazing talent. Shaw's the greatest clarinet player I ever heard. It's hard to play the way he plays. It's not an overblown orchestral style. He makes so many incredible shadings."

The obituaries noted that he had been married eight times, three of them to movie stars. He was married to Lana Turner, Betty Kern (daughter of Jerome Kern), Ava Gardner, novelist Kathleen Winsor, Doris Dowling, and Evelyn Keyes. He had contempt for movie women, referring to them as "those brass-titted Hollywood broads," but he never tired of telling which among them he had picked off, aside from those he had married. Winsor, who was born in 1919 and died in 2003, wrote Forever Amber, a novel set in England in the court of Charles II. Like the Grace Metalious book Peyton Place, it caused an uproar for being "dirty" and was banned in Boston back when that distinction made success a certainty: it was one of the best-sellers of its time.

Asked by the newspaper LA Weekly why he married so many times, he said,

"Because I was famous. That attracts women like flies, and you couldn't just shack up in those days. I was nineteen the first time I married, to a girl named Jane Cams. Her mother came and got her, and the marriage was never consummated. Then, when I was twenty-three, I met a nurse named Margaret Allen at a party, and she moved in with me two days later. We were together three years, and the last year was hopeless. She was Catholic and we didn't want children, but she had a problem with the idea of contraception. She had tremendous guilt. You know that Catholic shit people go through? She knew better, but she couldn't deal with the emotion."

Because he was famous? Not at nineteen and twenty-three respectively.

Artie Shaw was what the British call a cad and Americans call a heel, one of only four men I've ever known to recount their sexual conquests. He was solipsistic and cruel, a man who could never maintain a friendship for very long. His was a dispassionate destructiveness, and he could destroy a friend with no more feeling than a shark taking off a leg. He told me once that when he was young, his mother said she would leap out the apartment window if he left home, and he told her to go ahead and do it. "And," he said, "when I got down on the street, her body wasn't lying there."

Artie must have been proud of that story, for he told it to lyricist Sammy Cahn as far back as the late 1930s. Sammy recounted it in his autobiography I Should Care in these words:

"Artie said, 'You must never worry about your mother.''What do you mean?' He said that many times he'd tried to leave his own mother, on which occasions she'd scream at him, 'By the time you get downstairs my body will be in the street!' Finally he upped and left her anyway. I said, 'What happened?' He said: 'When I got downstairs she wasn't there.'"

The story is vivid, but it has a problem: it's not true. The Trouble with Cinderella, his "autobiography" (I use the word tentatively, because it's not that), relates that when at seventeen he left for Cleveland to join a band, he sent for her, she came out to "take care of him", and they lived together there for three years. When Artie encountered his father in California, the latter pleaded with him to intercede with the mother to take him back. Artie did. She refused. When Artie moved to New York and had to wait out his union card for six months, she worked to support him in an apartment in the Bronx. And, after the war, and his discharge from the Navy, he writes, "My mother still had to be supported."

So what's the point of the story he told Sammy and me?

Despite his affectations of reclusiveness, he never tired of talking about himself, as countless long interviews reveal. I do not recall an anecdote he ever told me that was not in some way intended to convey a sense of his own superiority to everyone. He told me a story about speeding in his car on Broadway in New York and killing a pedestrian who stepped into the street. Peter Levinson, the publicist, who once worked for him, said, "He told me that story too." It's also in the autobiography. I can believe it happened.

For among his aberrant qualities was his lunatic driving. He was the most dangerous driver I ever encountered. He thought the road was all his, or should be, and no one could be allowed to be in front of him. If any car was, he would try to pass it, and once he passed a bus as we were approaching a curve in the road! We made it, I'm happy to say, but I was left shaken. In her first autobiography, actress Evelyn Keyes said that he once tried to pass on a highway when he was driving a big recreation vehicle. Once he and I were on our way from Ojai to Santa Barbara on a winding road through the mountains. It's a road I know well. At one point there was a one-lane bridge. Everyone slowed up to peer to see if anyone else was approaching, and local people did this with courtesy, drivers yielding the right of way for mutual safety. Immediately at the end of this bridge, the road dropped in a steep incline; it was such a horror that it has been replaced. As we approached, I said, "Artie, you'd better cool it. This is a dangerous bridge coming up." He didn't even slow down. Fortunately, no car was approaching us, but after leaving the bridge we were airborne for a couple of seconds.

After that, wherever we went, I always made sure I did the driving. Once we went to a concert in Los Angeles. On the way home, we were talking about Charlie Parker, and I mentioned how disconcerted I had been when I first heard him and Dizzy Gillespie.

There was something new in the air when Shaw formed his first band. There had always been more influence of classical music on jazz than many of its fans and critics realized. The bebop era was seen as having its harbingers in Charlie Christian and Lester Young. But there were earlier signs of the music that was to come. If Bix Beiderbecke was interested in the French Impressionist composers and in Stravinsky, so was Artie, who told me he roomed for a while with Bix when he first arrived back in the city of his birth, New York. And Artie says he was deeply influenced by Bix, trying to play like him, but on saxophone.

Artie said, "You are too young to know the impact Louis had in the 1920s," he said. "By the time you were old enough to appreciate Louis, you had been hearing those who derived from him. You cannot imagine how radical he was to all of us. Revolutionary. He defined not only how you play a trumpet solo but how you play a solo on any instrument. Had Louis Armstrong never lived, I suppose there would be a jazz, but it would be very different."

He described how, when he was nineteen, he drove from Cleveland, where he was working with the Austin Wylie band, to Chicago to hear Armstrong. Oddly, he doesn't mention this pilgrimage in The Trouble with Cinderella.

The chromaticism in jazz increased as musicians absorbed the harmonic and melodic material of Twentieth Century classical music. Artie said, "I was listening to the same things that Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker were listening to a little later on — the dissonances, as we thought of them then, of Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Bartok. Another factor was that I was not thinking in two-bar and four-bar units. The lines would flow over bar lines. That's simply being musical, of course. In the Mozart A-major quintet, I can show you a phrase that's eleven bars long followed by one that's nine, and they're completely organic. We have been so trained to think of music in even numbers. Have you ever noticed that the things of nature — the number of kernels in a corn row, the number of peas in a pod — occur in odd numbers?

"Incidentally, while we're on the subject of Dizzy and Charlie, can you answer a question for me? Why hasn't Dizzy, one of the greatest trumpet players we've ever had, been given the recognition Charlie has?"

"Because," I answered, "he isn't a junkie who died young and tragically. Haven't you ever noticed that America immortalizes those who live screwed-up lives and die young? America makes legends of such people. Lenny Bruce, Hank Williams, Bix."

"Billie Holiday, Bunny Berigan, Lester Young," Artie added.

I said, "It's a corollary of puritanism. Dizzy has been successful, he's gregarious, he likes laughter, he was the great teacher, and for that reason full approval is withheld. If Bill Evans hadn't lived a tortured life, he might never have been given the recognition he's received. There is a kind of condescension in the phenomenon. So long as you can look down on someone with pity, it's okay to praise him."

"I think you're right," Artie said.

We had so many such conversations in cars. He said something once that still comes to mind when I find some road sign confusing. He said, "California road signs are designed to tell you how to get some place if you already know how to get there."

I ran into Sammy Cahn at a luncheon not long after I read his scathing chapter about Artie in his autobiography. I said, "My God, Sam, you certainly took Artie Shaw apart."

Sam said, 'That's only the half of it. My lawyer made me take out most of what I wrote." His book contains this passage: "I've told about some of the warm good memories of my life among the greats. To play it straight before the finale, I think I should balance things out with my private saga of Artie Shaw — which started out sweet and went sour. Artie Shaw, head man in the can't-win-them-all department. …

"Shaw and I immediately took to each other — at least I thought he took to me and I know I took to him. Why not? I was a young kid in my twenties, struggling like hell to stay alive and get going in the business. I had yet to have a hit — it was even before Bel Mir Bist Du Shon. Artie Shaw had more than arrived. He was beautiful. He stood tall. He had his hair. He and his magic clarinet were Sir Galahad with a lance."

One story that he did not put into the book, Sammy said, was this one:

At the peak of his band's success, Artie hired a young musician, a saxophone player as I recall, who had just been married. His young wife was beautiful, and when the musician brought her to a rehearsal, Artie immediately cast his eye on her. Somebody said to him, "Artie, please! Leave her alone. She's his whole life, he lives for her."

So Artie went after her and destroyed a marriage.

One story Artie he told me was about Frank Sinatra. Sinatra had gone through his terrible travails at Columbia Records, with a&r chief Mitch Miller forcing him to sing things like Mama Will Bark. Then Columbia dropped him from the label, no matter how much money he'd made for the company in the immediate past. Sinatra's anxiety was terrible, probably the reason for his voice problems, including a bleeding throat.

Sinatra, by his own admission, was then at the lowest ebb of his life He came to Artie in his hotel room, to beg for money. "He'd have done anything to get back on top," Artie said. "He'd have sucked your cock, he'd have done anything." I was disturbed by this contempt for a colleague's anguish, Artie's sense of superiority even in that situation.

As it happened, I saw Sinatra perform during that dark period of his life. He played the Chez Paree in Montreal. I knew some of the musicians in the band, including the bassist Hal Gaylor, still one of my friends. The drummer was Bobby Malloy. They were apparently the only two members of the band Sinatra liked.

Sinatra was then married to Ava Gardner. She was in Africa making Mogambo with Clark Gable while Sinatra was playing that Chez Paree engagement. Hal told me Frank would retreat to the manager's office and try to reach her on the phone. He was told that she'd been flown back to London where she was in hospital. Sinatra called the hospital, to be told she had gone out for the evening.

"He was beside himself," Hal said.

Sinatra didn't like what the brass section was doing, and told them so. They were instantly hostile. Sinatra told them, "Okay. Out in the alley. One at a time." But he did like Hal and Bobby Malloy, and made that plain to everybody too. Years later, Sinatra came to see Tony Bennett when Hal was Tony's bassist. He said to Hal, "But where did they get the rest of those guys? Out of the yellow pages?"

He came out on stage the night I saw him looking as if he were ready for a fight.

None of the loose, humorous grace of his later Las Vegas and TV performances. He seemed to be saying to the audience, in his body language, "Just one of you bastards laugh at me ... .""

He hadn't sung more than half a chorus when I knew and said, "They'd better never ever try to write this guy off again." Not long after that, he signed with Capitol Records, and began the second soaring period of his career.

"He was very good to Bobby and me," Hal said. "He took us out to some other gigs around Quebec, mostly at hospitals." That's a side of Sinatra that most people don't know, and within the profession, stories of his kindness and generosity are legend. Hal admired a pair of shoes Sinatra was wearing. "What size are you? "Sinatra said. "Eleven," Hal said. "Too bad," Sinatra said, "these are nines." At the end of the engagement, Sinatra told Hal and Bobby Malloy to go to a renowned maker of tailored shirts. Sinatra had paid for a batch of shirts for each of them. "They were beautiful shirts," Hal said. "I wore them for years." That, along with Sinatra's dark side, was the sort of detail for which Frank is always remembered.

I never heard of a thing that Artie Shaw ever did for anybody.

Howie Richmond, the respected music publisher who was Sinatra's press agent at that dark period after Columbia Records, in later years lived right across the Tamarisk golf course from Sinatra in Rancho Mirage, California. Howie told me once, "Frank never had a friend he doesn't still have."

Artie hardly ever retained one.

And he never tired of denigrating Sinatra. LA Weekly in its November 12-18 1999 issue ran a long interview with him, written by Kristine McKenna. He told her:

"Sex can create tremendous chaos, but it can also be the source of great joy. My relationship with Ava Gardner was absolutely glorious that way." [Every one who ever spent a night with her said it was glorious.]

Shaw continued: "Ava came to see me one time after she'd been married to Sinatra for a while. She was having trouble with him, and she said to me, 'When we were doing it'— that was her way of saying it — 'was it good?' I said, 'If everything else had been anywhere near as good, we'd have been together forever and I'd never let you out of my sight.' She gave a sigh of relief. I asked why. She said, 'With him it's impossible.' I said I thought he was a big stud. She said, 'No, it's like being in bed with a woman.'"

I don't believe it. Gardner was famous for an uncensored vocabulary. In his memoir No Minor Chords, Andre Previn recounted meeting her at a party when he was seventeen. She would have been about twenty-three. She made a pass at him, and he, being very inexperienced, fumbled the opportunity. A year or so later he ran into her at another party. This time he made a pass at her. She said, "Fuck off, kid."

Once she was asked what Sinatra was like in bed. She replied, "A hundred and thirty-five pounds of hot fuck." So I can't imagine her saying "doing it."

Sinatra really seems to have bothered Artie. The woman interviewing him asked:

"Do you think Sinatra was talented?"

To those of us who write and sing songs, he was more than that: a genius. Both Placido Domingo and Luciano Pavarotti say that Sinatra was the greatest singer they ever heard. Many other opera singers will tell you the same.

Artie told McKenna:

"He was very good at what he did, if you care about that. Personally I find it hard to believe that a man can walk around with his head filled with those lyrics, 'I get a kick out of you . . . .' That shit he did. He wanted it very badly, though, and he's the only guy who could've come along and put Bing Crosby away, because Bing was a hell of a singer at his best. After Louis Armstrong, he was the first great jazz singer. Sure, he did White Christmas— he had to. It's part of the lexicon. But he was a long way from square. He was a terrible person, but so was Frank. I don't care about Sinatra. He bores the shit out of me.

"

A footnote: I know all the lyrics to all the classic 1920s, '30s, and '40s songs, and the way Shaw breathes and phrases the ballads tells me that, like Lester Young, he too knew them, for all his affected condescension. That's why his playing sounds vocal: he is singing in his head.

At some point after World War II, he recorded an album of Cole Porter with his band and the Meltones, Mel Torme's vocal group. One of the singers was Virginia O'Connor, called Ginny, who would later sing with a vocal group in the Tex Beneke-led Glenn Miller ghost band and marry its pianist and arranger, Henry Mancini. Long after that, when Mancini had become inestimably wealthy — he admitted to me that his royalties exceeded those of Jerome Kern — Ginny became the key figure in organizing the Society of Singers, whose purpose was to help older singers who had fallen on hard times, such as Betty Hutton, living in poverty, and Helen Forrest, poor and crippled with arthritis. She had recorded with Artie, but band singers did not share in the boss's royalties. In Forrest's case, Artie got them all.

Ginny threw a huge party at the lavish Mancini home to publicize the society and begin collecting money for the organization. She has done this sort of thing repeatedly, forming the Mancini Institute, devoted to the summer training of gifted young musicians. (Mancini left a very big scholarship for young composers at the University of California in Los Angeles.)

After one of Ginny's charity parties, limousines were lined up to take home the millionaire guests.

"The Mancinis live like oil sheiks," Artie said. "Musicians shouldn't live like oil sheiks." Who, then, should? Oil sheiks? Ken Lay? The underlying reality, of course, is that the Mancinis could buy and sell Artie, even though he had never had to work a day since Begin the Beguine.

And of course, Ava Gardner was always high on his list of people to trash.

I met Gardner once. It was at Birdland in New York. She had come in to hear the Woody Herman band, and between sets Woody introduced me to her, saying I was a songwriter. She asked what songs I had written, then asked who had recorded them. I said, "Tony Bennett." She said, "I hate Tony Bennett!" And since Tony had been good to me, the first major singer to record my work, and excepting Sarah Vaughan, the most supportive, I said with heavy sarcasm, "Who would you like to hear record them, Miss Gardner?"

She said, "Frank Sinatra."

At the end of the evening, I said to Woody, "So. I guess she's not over Frank Sinatra.”

Woody said, "No, the one she's not over is Artie Shaw."

Many of the obituaries on Artie, including that in the New York Times, quoted me, because it was known that we were friends. Well, at one time, we were, or at least, like Sammy Cahn at an earlier time, I thought we were.

Artie lived fairly near me in California — Newbury Park is about a half hour drive from Ojai. At one period we were almost inseparable, talking constantly on the telephone, and he was often at our house. One Halloween we had just finished dinner when the doorbell rang. Artie answered it. There stood several kids in costume, looking up, eyes alight, one little girl dressed as a fairy, and my wife gave Artie candies and other things to give to them. Behind the children were their young parents, who asked if they could take a picture. Artie said, "Of course," and the father took it. Afterwards my wife said, "Those kids will grow up never knowing the identity of the man in the picture."

Woody Herman disliked both Artie Shaw and Benny Goodman. And it was not a matter of jealousy. If Goodman and Shaw were the pre-eminent clarinetist bandleaders of the 1930s and early forties, Woody was the third, often underestimated even by himself. The first night I knew him, he said, "I never was much of a clarinetist." That endeared him to me instantly; and he was better than he knew.

Once when Woody was playing Basin Street East, I was sitting at a table with him during intermission when Benny Goodman approached. Woody introduced us; it would be the only time I ever met Goodman. Goodman made some disparaging remark about Woody's clarinet playing. Wood said, "Well, that's the way it always was, Benny. You could always play that clarinet and I could always organize a band." And that's the truth: Goodman would no sooner assemble a great band than he would begin to demoralize it, with contemptuous treatment of his musicians. But in his case, it was often a kind of insensitive absent-mindedness, not a willful cruelty, like Artie's. Singer Helen Ward was rehearsing with Benny and a trio at Benny's studio in Connecticut. The trio was led by Andre Previn, who assured me that the story is true; and so did Red Mitchell, who was the bassist. Helen Ward said, "Benny, it's getting a little cold in here." Benny said, "You're right," left the room, and returned wearing a sweater.

The late Mel Powell, perhaps the most important pianist who ever played in the Goodman band and certainly one of its finest arrangers, and his wife, the actress Martha Scott, had a theory about Benny. They said there must be an electric cord in his back, and sometimes he was plugged in and sometimes he wasn't. He called everyone Pops because he never could remember anyone's name, and some of the musicians speculated that he probably called his daughter and his wife Pops.

I got into trouble with Woody over Artie Shaw. We were talking about the big-band era. Artie and Benny inevitably came up, and I said that I thought Shaw was the better clarinetist. Woody answered with a frosty Milwaukee tone of which he was a master. The a's are very flat, as they are in Chicago, and when he called you "Pal," you knew you were in trouble. "Listen, Paaal, you don't play that instrument, and I do, and I'm telling you, Benny's the better clarinetist."

When it came to playing with swing at rapid tempos, I think that's true. The day after Artie's death, a Manchester Guardian obituary said, "Shaw's bands can seem rhythmically stodgy compared with those of Goodman," which is true. But the Shaw solos are their finest moments. It was the wonderfully lyrical and romantic quality of Shaw's playing that entranced me at an early age, and still does. One wonders how a person of his character could produce such beauty.

Shaw's clarinet work is known mostly — and in many persons, entirely — from his big-band records, in which his solos were restricted, perhaps eight bars or even four, of a chorus, excepting a few extended excursions such as those in Stardust or Concerto for Clarinet. He was able to stretch out in some of the records he made by small groups drawn from the personnel of the band. Benny Goodman did that: made recordings in a small format such as his sextet. Other bandleaders emulated this, as for example Tommy Dorsey's Clambake Seven, essentially a Dixieland group, and Woody Herman's Woodchoppers, which varied in size. Shaw had several such groups, notably the Gramercy Five, named for the prefixes to New York City telephone numbers. In the Gramercy five, and as if to show his allegiance to classical music, Shaw had John Guarnieri play harpsichord

But even these small-group recordings did not let us hear what Shaw could do in an expanded context. The early records, even the Gramercy Five discs, were made in the age of the 78 rpm records, which were for the most part limited to a three-minute format. And by the time tape came into general use, Shaw was not recording.

In 1954, however, he had a septet with the incomparable Hank Jones on piano, Tal Farlow on guitar, Irv Kluger on drums, Tommy Potter on bass, and Joe Roland on vibes. "We had been working together and the group sounded so good," Artie said, "that I thought it should be recorded. So I just took it into the studio and recorded it myself." The tracks were eventually made available on a double-CD package on the MusicMasters label [01612-65071-2]. They suffer from the fact that there are four chordal instruments in the ensemble, and they somewhat get in each other's way, particularly in sonority. But they offer us Shaw the astonishing jazz clarinetist at the top of his form, the pinnacle of his powers, in circumstances that permit extended solos. It is Shaw, pure lyrical, endlessly inventive, Shaw, with elements of bebop assimilated into his playing.

![]()

More than one clarinetist, Phil Woods among them, has explained to me the problem of playing bebop on the clarinet as opposed to the saxophone. It has to do with the nature of the fingering. The saxophone, as they put it, overblows at the octave, which means that if you press the octave key the music jumps up an octave. The fingering in the higher octave is the same as that in the octave below. But the clarinet overblows at the fifth, which means that the fingering in the higher register is different. This explains why a lot of musicians play a different style on clarinet than on saxophone, although a number of them have overcome the problem by utter mastery of the instrument.

When the innovations of bebop — including the chromaticism and angular lines and shifting rhythms — came into jazz, Benny Goodman loathed them. Woody Herman never attempted to incorporate them into his playing, choosing to let the younger musicians around him explore what Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker had brought to the music. He reveled in bebop, in fact, and was always delighted to have Parker sit in with the band. Indeed, he was one of the first to commission arrangements (The Good Earth, Down Under) from Dizzy. Shaw fell into a different place. Such was his approach to the clarinet that even in the pre-bebop days, there is — as there is in the piano of Mel Powell and the tenor solos of Coleman Hawkins — portent of what is to come. I once told Mel Powell that I thought what he was doing in the Goodman Columbia recordings was proto-bop. Mel loved that term, and I think that's what it was. Shaw loved Parker and Gillespie, and told me once, "We were all listening to the same things," meaning in classical music. Dizzy used to refer to attending a symphony concert as "going to church."

Those 1954 tracks show us what a great and inventive jazz musician Shaw really was. They are spectacular records, and alas little known by most jazz fans. And Shaw perversely gave it all up after making them.

He broke up his first band at an engagement at the Pennsylvania Hotel in New York around Christmas of 1939.

"His income at this Depression time was about a quarter of a million dollars a year," Sammy Cahn wrote, "but he'd been writing articles attacking jitterbug dancing and had been making noises about quitting ....

"I went upstairs to Artie's room and I talked to him, 'Artie, it's not just quitting a band. It's quitting sixteen people and their wives, children, mothers, fathers, lovers, friends. You just can't do this. Artie Shaw is a million dollar industry."

"I can do it.'

'"Please don't do this.'

“'I'm doing it.'

"'Don't you owe anything to these guys?''

"I owe them nothing.'

"Which could be his epitaph: 'I owe them nothing.'"

And Shaw did indeed disband. He moved to Mexico and lived near Acapulco when it was still a sleepy little fishing town. During this sojourn, he heard a song called Frenesi. He returned to the United States and recorded it with a thirty-two-piece studio orchestra. It became his second major hit.

During one of these periods of flight-from-fame, Count Basie urged him to return, saying that the business needed him. "Why don't you come back?" Basie said.

Artie said, "Why don't you quit?"

Basie got the best of it. He said, "To be what? A janitor?"

But after those 1954 recordings, Shaw meant it. He left music as a profession forever, which, on the promise of those recordings, is to our eternal loss. For a time he said he was a movie producer; I know of no film he ever produced. But mostly he said he was a writer. There was a sign by the doorbell of his house in Newbury Park. It said, "This is a writer's house. Do not ring this bell." I suppose he could have had the bell disconnected, but that little note had just the right tone of aggression and contempt.

It is one thing to say you are a writer, it is another to be one. Artie gave up a brilliant career as a first-rate musician to become a third-rate writer. His first book, which received a good deal of attention, was The Trouble with Cinderella. It was probably easy for him to write: it was about his favorite and perhaps only subject, himself. More about it later.

Born Arthur Arshawsky on the Lower East Side of Manhattan on May 23, 1910, he grew up from the age of six in New Haven, Connecticut, with his mother. His father had at some point deserted them, and Artie told me that in childhood he felt like a double outcast: outcast as a Jew, and outcast within the Jewish community because Jewish men just didn't abandon their families.

At fourteen Arthur got his hands on a C-melody saxophone and won a five-dollar prize for playing Charley My Boy. He was amazed that money could be earned so easily and decided to make music a career. But he couldn't read music. Nor did he know anything about keys and transposition, and when he acquired an alto saxophone, which is tuned in E-flat, the notes came out all wrong. He quickly learned the craft, however, and a year later he was a working road musician By the time he was seventeen he was working in Cleveland with the Austin Wylie band. He lived there for three years. He was with the band of Irving Aronson 1929-1931.

By the age of nineteen he was back in the city of his birth, and only a few weeks later he was the top lead alto player in the New York radio and recording studios. He freelanced on record dates and at CBS, sharing some sessions with Jerry Colonna, the bemustached trombonist who later became a comedian on the Bob Hope Radio Show. He used to let out a crescendo howl that would turn into the first line of a song. Hope featured this gimmick on his show.

Another seat-mate on those studio dates was Benny Goodman, of whom Shaw spoke with condescension.

At that time Shaw was immersed in Thorstein Veblen. The Wisconsin-born political economist, who taught at the University of Chicago and Stanford, enjoyed a vogue in the first decades of the twentieth century, although his writings were difficult to penetrate. He spoke twenty-five languages and had a gargantuan grasp of history, art, literature, science, technology, agriculture, and industrial development. He has fallen from fashion in our epoch but his was one of the finest minds of his time, and much of what he wrote appears urgently pertinent today. His 1899 book The Theory of the Leisure Class made him instantly famous. He wrote a total of nine books, dividing society into a parasitic "predator" or "leisure" class, which owned business enterprises, and an "industrious" class, which produced goods, and he was highly critical of business owners for their narrow "pecuniary" values. He was unacceptable to the Marxists, who said he was "not one of us," and anathema to the capitalist class. And, while not writing of it directly, he had a visionary foresight of what would become of the planet's environment. Indeed, he coined the phrase "conspicuous consumption."

When he was on record or radio dates, Shaw read between takes. This, he said, disconcerted Goodman, who asked one day what he was reading. Shaw showed him The Theory of the Leisure Class. Goodman walked away without comment. But from then on he addressed Artie as G.B. Finally, it wore on Artie's nerves and he said, "Okay, I give up. What does it stand for?" Goodman said, "George Bernard." Artie told the story with a mixture of mockery and fathomless contempt.

His career as a bandleader began by accident. Joe Helbock, owner of the Onyx Club, a former speakeasy frequented by musicians, was planning the first New York "swing" concert at the Imperial Theater. He asked Artie to put together a small group to play in front of the curtain while the setup was being changed. Artie did, but as usual he did it in his own way. He assembled a group comprising a string quartet (reflecting his yearning for classical respectability)and a small rhythm section without piano (which he thought would be too strong for the texture of such a group) and himself on clarinet.

He wrote a piece that he didn't bother to name, calling it what it was, Interlude in B-flat. He and his colleagues went onstage the evening of April 7, 1936, and played it to an astonished murmur from the audience, which included musicians. When the piece ended, the audience roared its approval. But Shaw hadn't written any more music for the group, and all he could do for an encore was to play the piece again.

Somebody made an acetate recording of this performance. Many years later a fan sent Artie a tape of an Australian radio broadcast containing, to Artie's bafflement, the Interlude in B-flat. He telephoned the broadcaster in Australia. The man said he had obtained the recording from someone in Seattle, who turned out to be a collector. Artie tried calling him; the man didn't return his calls. We can imagine how apprehensive the man was — he could presume the recording had been made illegally. Finally, Artie left a message: "Look, I'm not trying to make trouble for you, I just want that recording. And if you don't answer my call, I'm sending the police."

The man returned the call and told Artie he had found the recording in a stack of old acetates he'd bought. He was a long-time Shaw fan, recognized the style, knew this piece was not among the known Shaw recordings and, having read The Trouble with Cinderella, realized what he had. And of course he was only too happy to send Artie a copy of the record. It was very worn, but Artie ran it through digital recording equipment with an engineer and cleaned up the sound considerably.

Shaw claimed that he did not set out to be a public figure, did not even want to form a band. He wanted to become a writer, and studio work was financing his studies. But nature had given him a superb ear, infallible taste, and a steely will about developing musical technique. After the Interlude in B-flat performance, a booking agency approached him about forming a band. He said he was interested only in finishing his education at Columbia University. He was asked how much money that would take. He took a deep breath and blurted the largest figure he could think of, $25,000.

He was told he could earn $25,000 in a few months if he organized his own band. And so he formed a band, but hardly the one the agency had in mind. Following the pattern he'd set for the Interlude, the group contained a small jazz front line, a rhythm section, and a string quartet. It failed. So he broke it up and organized a big band with conventional saxes-and-brass instrumentation. "If the public wanted loud bands," as he put it, "I was going to give them the loudest goddamn band they'd ever heard."

To be continued

The following video tribute to Artie features the Rough Ridin’ track from Artie Shaw: The Last Recordings MusicMasters double CD with Joe Puma, guitar, Hank Jones, piano, Tommy Potter, bass and Irv Kluger, drums.

© - Steven A. Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

This is part two of Gene Lees’ three part feature entitled The Anchorite which he published in his Jazzletter, June-August 2004.

By way of reminder, an anchorite is a religious recluse… a deep believer...one who holds dear to their moral and ethical principles.

Gene’s description of what Jazz was during its earliest manifestations at the beginning of the 20th century through The Swing Era is a classic account of how the music evolved during its first, three decades of existence.

His discussions with Artie about why he left the music business, sociocultural trends 20th century American culture and the trivialization of American popular music contain much food for thought, to say the very least.

The Anchorite: Part Two

“He recorded Begin the Beguine on July 24, 1938. It immediately became the number one "platter" in the United States, held that position for six weeks, and went right on selling. Shaw's income went to $30,000 per week. One reason he could earn such money was the sheer number of pavilions and ballrooms in America. He told me that at the peak of the big band era, a band could play a month of one-nighters in Pennsylvania alone.

Begin the Beguine was an unconventional long-form tune and its success amazed Shaw. In a 2002 interview with the Ventura Star (Shaw lived, as I do, in Ventura County) Shaw said that [Cole] Porter "shook hands with me and said he was happy to meet his collaborator." Shaw's response to this is revealing. For a man who affected to be uninterested in money, it is crassly materialistic, and certainly ungracious: "So I said, 'Does that go for the royalties, Mr. Porter?'" One wonders what opinion of him Porter carried thereafter. And, incidentally, Porter got only royalties from the song's publisher; Artie got all the royalties from record sales.

In addition to the RCA reissues of Shaw's 78 rpm recordings, there were five albums on the Hindsight label containing as many as nineteen tracks each, drawn from radio broadcasts. These are casual performances and some of the tracks stretch out to nearly six minutes.

I listened to test pressings of those recordings with Artie in the big, vaulted, second-floor room of his home, whose walls were covered in books. He said, "When you went into the recording studio in those days, there was no tape and you knew it was going to have to be perfect. You wouldn't take chances doing things that might go wrong. But on radio broadcasts, you could do anything. It didn't matter. You never thought of anybody recording it and forty years later releasing it! The recordings were done under better conditions. You had better balance. But you didn't get anything like the spontaneity you have here."

The Hindsight records reveal what the band played like in the late 1930s but cannot reveal what the band actually sounded like. Recording technique was too primitive. The bass lines are unclear and the guitar chords all but inaudible.

What you get, really, is the upper part of the harmony, and you cannot follow the lines in the voicings. When a local Ventura bandleader borrowed some of the charts to perform them in a concert, I attended the rehearsals with Artie.

He said, "Well, what do you think?"

I said. "Now I could hear the bottom of the orchestra." I confessed that I was not all that excited about 1930s bands that contained only four saxes, two altos and two tenors. My taste for big bands grew warmer when baritone saxophone was added, as in the Goodman band with Mel Powell that recorded for Columbia. Furthermore, you couldn't hear the bass player at all on a lot of early big-band recordings, and without the bottom of the harmony, one doesn't fully feel or understand what is going on. (There is a 1992 Bluebird CD called Artie Shaw: Personal Best, in which Orrin Keepnews remastered the music so that you can hear the bass.)

In the first flush of success, Artie made about $55,000 in one week, equivalent to $550,000 today. The superlatives were flying, including the statement that he was the best clarinetist in the world. As he was leaving a theater in Chicago, aware that he was becoming rich at an early age, a thought crossed his mind. "So what if I am the best clarinetist in the world? Even if that's true, who's the second best? Some guy in some symphony orchestra? And is there all that much difference between us? And how much did he earn this week? A hundred and fifty bucks? There's something cockeyed here, something unfair."

John Lewis used to make the point — adamantly — that jazz evolved in symbiosis with the American popular song, although it did introduce a jaunty American rhythmic quality which evolved rapidly in the next ten years with George Gershwin, Richard Rodgers, and, later, Cole Porter, Arthur Schwartz, and more, the best songs written for Broadway musicals. But even non-Broadway American song grew in beauty, as witness Hoagy Carmichael's Stardust. Jazz, John Lewis said, drew on this superior material for its repertoire, and the public in turn was able to follow the improvisations against the background of songs it knew. Jazz grew up on the American song; jazz in turn influenced it, as especially witness George Gershwin and Harold Arlen.

Popular legend has it that the craze for dancing began with publication of Irving Berlin's Alexander's Ragtime Band in 1911. It's not true. The music publisher Edward B. Marks said, "The public of the nineties had asked for tunes to sing. The public of the turn of the [twentieth] century had been content to whistle. But the public from 1910 demanded tunes to dance to."

Puritan constraint kept dancing polite and stuffy in the nineteenth century. But with ragtime, that changed. Black dancers supplanted the cakewalk, two-step, waltzes, schottisches, and quadrilles with the Turkey Trot, Bunny Hug, Snake, Crab Step, and Possum Trot. Soon dancing was in vogue wherever it could be done, and social reformers, "religious leaders" and others condemned these dances as "sensuous", which they were, the beginning of the end of the Edwardian or Victorian era. There were even attempts to pass legislation outlawing ragtime.

Then along came a wholesome young couple, Vernon and Irene Castle, to tone down and tame some of these dances, and as the complainers grumbled their way into silence, the Castles became the major stars of their time, imitated in everything from dance steps named for them to their clothes. Irene shed her corsets for looser clothes, and women everywhere followed her example. When because she was in hospital for appendicitis, she cut her hair short. Millions of women followed her example. Dancing became a national and even international craze. The Castles, as big in France and England as they were here, became wealthy.

With the advent in 1914 of World War I, Vernon, who was English, went home to join the Royal Flying Corps. He flew more than 150 missions over the Western Front. Ironically, when he returned to the United States to train American pilots, he was killed when a student made a landing mistake. Irene's life and career were destroyed. But the Castles' influence went on.

Before the war, their chief collaborator had been James Reese Europe, the black bandleader who in 1910 founded the Clef Club orchestra made up entirely of black musicians. They provided much of the dance music for New York society. He was such a perfect dance conductor that Irene said Jim Europe's "was the only music that completely made me forget the effort of the dance." He became their music director in 1913, and soon was composing as well as conducting for them. She found him almost uncanny in choosing the right tempos for their dances. But with the coming of war, Jim Europe was asked by the military to form what would be the finest band in the U.S. Army. When the U.S. entered the war, he went to France with "The Harlem Hellfighters Band," as it was called, with a complement of forty-four men. They ended up attached to the French army.

With the war over, he returned to New York to resume his soaring civilian career, making a few records. On May 7, 1919, he was stabbed by his drummer, Herbert Wright, and died. He was twenty-eight.

The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz states that "it cannot be emphasized too much that jazz music was seen initially by the mass American audience as dance music." It was the arranger Ferde Grofe’ who (for the Art Hickman band in San Francisco) first wrote for "sections" of saxophones, trumpets, trombones, and rhythm. This permitted changes of coloration between one chorus of a song and the next. Paul Whiteman hired him and encouraged him to elaborate on what he had done for Hickman. This kind of scored dance music became known as "symphonic jazz", a term that later listeners found confusing, since it had little if anything to do with the symphony orchestra. Other bandleaders like Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, and Jean Goldkette followed his example. Whiteman has been patronized by "jazz writers" and historians for not playing jazz, which was never his intent in the first place, or for using the sobriquet "King of Jazz", coined by some press agent, and even on playing on the obvious pun of his surname. But his bands at one period had a strong jazz feeling, and had something in common with that of Jimmie Lunceford, namely very cohesive section work, tight and disciplined, which may be due to the fact that they had the same teacher in Denver, Colorado, Wilberforce Whiteman, Paul's father.

The "big bands" continued to evolve during the 1920s, settling eventually on an instrumentation of four saxophones (two altos, two tenors), trumpets, trombone, and rhythm, which instrumentation expanded in the early 1940s. A number of the early bands were part of the booking stable of Jean Goldkette, including his own band, McKinney's Cotton Pickers with Don Redman as its arranger and music director, and a band called the Orange Blossoms, which evolved into the Glen Gray Orchestra with arrangements by Gene Gifford.

The beginning of the swing era is usually dated to the sudden success of Benny Goodman in 1936, but musicians who lived through that era often give the credit to the Glen Gray band. Artie called it "the first swing band." It was the first white band to pursue a jazz policy and put its jazz instrumentals on record. Gil Evans was a fan of that band.

The fans, perhaps led by the "jazz writers" of Down Beat, liked to divide the bands into the swing and the sweet bands, showing a hipper-than-thou disdain for the latter. And there were both the "name bands" and regional bands, including the Jeter-Pillars band of St. Louis which had a high reputation in the profession though it was never nationally known. Many of the regional bands fell into the "sweet band"category, among them Mal Hallett, Russ Morgan, Dick Jergens, Ted Fio Rito, Gus Arnheim, Will Osborne. A few of them rose to national prominence, including Freddie Martin, Blue Banon, Shep Fields, Sammy Kaye, and Kay Kyser. (Guy Lombardo presented a special case. I was surprised to learn that Louis Armstrong admired that band, and so did Gerry Mulligan. Gerry gave me an insight: he said that the Guy Lombardo band was a musical museum piece, a 1920s tuba-bass dance band that had survived unchanged. Asked to do a radio interview with Lombardo I went to hear the band with an open mind, met Guy, and was impressed by both. What the band did, it did well.

The division between swing and sweet bands was never neat. All the bands, including those of Ellington and Count Basie, played ballads for dancers, no matter that the more rambunctious sidemen would have been delighted to play hot solos all night. And some of the sweet bands could play creditable jazz, including that of Kay Kyser. I liked that band — George Duning was one of its arrangers.

There were hundreds of places for dancers to hear the bands. They included hotel ballrooms, county and state fairs, amusement parks, and even roller- and ice-skating arenas. To those who listened to the late-night "remote" broadcasts from these places, their names became almost as famous as those of the bandleaders — Frank Dailey's Meadowbrook, for example. |n the mid- to late-1960s, bands were presented in movie theater between showings of the feature film. The bands were heard constantly on network radio.

With the rise of bands playing "hot" numbers, the vigorous dances of the pre-Jim Europe period came back to American popular music. The dances — and dancers — of Harlem were deplored by some of the white society as lascivious, but they were more than that. They were balletic and acrobatic to the point of being dangerous, and at the highest level, incredibly skilled. A few evenings after seeing a documentary on the dancers of Harlem, I was with Gene Kelly. I was naive enough to say, "You know, Gene, some of those people could really dance!" And Gene chuckled and said, "Nooooo shit."

These dancers were the start of the jitterbugs, and even some of the white kids got very good at this kind of dancing. In the ballrooms and arenas where the bands appeared, those who just wanted to listen crowded close to the bandstand, taking in the solos, while those who wanted only to dance remained well back of them; and a few went back and forth.

The dancers, in their millions, supported a large industry.

What is not understood by younger people, and I'm afraid at this point I must include many of those under sixty, is how big these bandleaders were, and, like rock stars of a later generation, they were brought into the movies. Paul Whiteman's was one of the first to be seen in a film. Much later, Harry James appeared in Swing Time in the Rockies (1942), Tommy Dorsey in Ship Ahoy (also 1942), which featured Frank Sinatra and Jo Stafford and a spectacular drum solo by Buddy Rich, and Woody Herman in a number of forgettable films and small features. Glenn Miller made two features. Sun Valley Serenade was released in 1941. Somewhat better was Orchestra Wives in 1942, which had a backstage story to it. In both films, the Miller band was better heard than on records, because of the superior sound in films.

![]()

Shaw and his band were in a forgotten film called Dancing Coed, then in the 1941 Second Chorus, one of the sillier of its ilk. In most of these films, the bandleaders played themselves as guests in the picture. And thus too Artie. During the shooting of Second Chorus an exchange occurred between Artie and either the director or assistant director. I must interject for those under fifty or sixty that in those days to explain that to do a hot dance, one of those jitterbug performances, was called "cutting a rug." Artie had some lines to read in the picture. He was to say to the audience, "Okay, kids, now we're going to cut a rug."

Artie refused to do it, telling the director:

"Look, I'm playing a character named Artie Shaw, right? Well, I consider myself something of an authority on this guy, and I'm telling you, he wouldn't say it!"

The line was omitted.

The film starred Fred Astaire as a dancing musician. How many musicians, other than Dizzy Gillespie, have you ever encountered who could really dance? One imagines a studio meeting with assorted executives, one of whom, striding the room, says, "I've got this great idea! We'll put Fred Astaire together with Artie Shaw, who's one of the hottest things in the business. We'll have Fred play a dancing trumpet player! It's great, just great."

No it wasn't. Artie, by the way, said it was hard to play for Fred Astaire. He said that Astaire (who actually played pretty good piano and creditable drums) had lousy time. Astaire's sidekick among the musicians was Burgess Meredith. The love interest was Paulette Goddard. In real life, she married Burgess Meredith. But Artie picked her off. Or so he said. She was another of his unkept secrets, along with Betty Grable and, he intimated, every other beauty in the movie industry, aside from the ones he married.

Shaw got involved with Grable when, in 1939, she was appearing on Broadway in

Cole Porter's musical Dubarry Was a Lady. Artie went to Hollywood to make his movie, constantly writing to her. Sammy Cahn recounted:

"Every night I'd go to the 46th Street Theater to talk with Betty and listen to her read these letters from Artie, the most marvelous letters in the world. He'd met that one girl in the world, darling Betty, for whom he'd give up everything else. And so on ....

"One night I was in Betty's dressing room and she was reading another of those beautiful letters from Artie, so beautiful you couldn't stand it. When I walked out onto the street the newsboys were hawking the headline: Read all about it! Artie Shaw marries Lana Turner! Lana was in that same picture with Artie, Dancing Coed. She was a year out of high school. He married her on their first date.

"After that I couldn't go back to the 46th Street Theater to see Betty Grable."

No one suffered his disdain as much as Lana Turner. Everything I've ever heard about her from friends who knew her evokes an impression of a girl who was almost pathetically sweet, urgently anxious to please. If you happen to watch one of her movies some time, notice the voice. There is quality of heartbreak in it, no matter what the role. I can only imagine what she felt when she read his derogations of her in newspapers. His wives were all alive to read his descriptions of them, which ran to one theme: their intellectual inferiority to him.

Publisher Lyle Stuart once tried to persuade Shaw to write a book about Lana Turner. Shaw said, "Oh, I couldn't talk about Lana." Next Day Stuart showed up at his New York apartment with a tape recorder. Stuart said, "He talked about Lana for three hours. When I left, I said, 'See?' He said, 'Okay. But I could never talk about Ava.' The next day I came back and he talked about Ava for three hours."

Sammy Cahn, in his chapter on Artie, wrote: "I'm pretty much convinced that eventually what you are is what you come to look like. A miser gets to look like a miser, a cunning man like a cunning man, a saint like a saint. Artie Shaw was once one of the handsomest men who ever lived. Now he looks like what he is." At that point, Shaw was bearded and mustached.

Artie read that passage, because he mentioned it to me. "And what the hell does Sammy think he looks like?" Like Igor Stravinsky, actually. I told Sammy that at lunch one day and he said, laughing, "I know!"

Everyone got the treatment. Asked late in his life: "What are your thoughts on Benny Goodman?" Artie said:

"Benny was a superb technician, but he had a limited vocabulary. He never understood that there were more than a major, a minor and a diminished. He just couldn't get with altered chords. We worked together for years in radio, and Benny was pretty dumb. His brother Freddy managed one of my bands, and I once asked him what Benny was like as a kid. He said, 'Stupid.' I said, 'How do you account for his success?' He said, 'The clarinet was the only thing he knew.' And it's true. He was sort of an idiot savant — not quite an idiot, but on his way. He didn't quite make it to idiocy."

I hate to say it, but that seems to be just about everyone's assessment of Goodman.

Lyle Stuart was not the only victim of Shaw's prolixity. In a JazzTimes column for the April 2005 issue, the writer and music historian Nat Hentoff, who said it was Shaw's recording of Nightmare that made him a jazz lover, continued:

"Years later, when I was New York editor of Down Beat, Artie Shaw would call me from time to time to discuss not only my limitless deficiencies as a jazz critic but also all manner of things, from politics and literature to other things that came within his wide-ranging interests. As soon as he was on the line, I knew that for the next hour or so my role was to listen. It was hard to get a word or two in."

Artie would orate for hours to anyone on any subject that crossed his mind, whether he knew anything about it or not. He did not know as much about classical music as he pretended or perhaps believed he did. Once when we had just emerged from a Santa Barbara department store, I turned on the ignition and the car's radio, which I keep tuned to the classical station, came on. We heard some music that neither of us recognized. I said, "Wait a minute, Artie, I think I know what it is. I think it's Stravinsky. Most of us are familiar only with the Firebird Suite, but that's distilled from the full ballet, which you rarely hear." I could hear Stravinsky's harmonic fingerprints all over the piece, and his orchestration, and even concealed allusions to the Firebird's principal themes. "I think this is the full ballet score," I said.

He scoffed. "Do you know how well I know Stravinsky? And I certainly know the Firebird." He was adamantine in his certainty that I was wrong.

Later on in the music the Berceuse theme emerged, and we were hearing indeed the full ballet score. It wasn't so much that he didn't initially recognize the music; I didn't either. It was his obstinacy in error that stays in my memory. And I saw other instances of his faking knowledge.

A day after Shaw died, one of the newspapers carried a headline on its coverage of the obituary: Swing-era great grew tired of music business. I think he enjoyed the attention he got from disdaining fame even more than he did the fame itself— and he did enjoy it, for all his denials. For his whole life, Artie Shaw guarded and treasured the prominence he thought he deserved even while affecting to deplore

it. It was in November, 1939, while Begin the Beguine was still a best-seller, that he made the first of his serial exits from the music business. A few cynics said the real reason for the move was that Glenn Miller had surpassed Artie's record sales.

Though he referred to Miller as a friend, he said of him, "He had what you call a Republican band, kind of strait-laced, middle-of-the-road. Miller was that kind of guy, he was a businessman. He was sort of a Lawrence Welk of jazz and that's one of the reasons he was so big, people could identify with what he did. But the biggest problem [was that] his band never made a mistake. And if you never make a mistake, you're not trying, you're not playing at the edge of your ability. You're playing safely within limits . . . and it sounds after a while extremely boring."

It was at that time that he organized his first Grammercy Five, which included Johnny Guarnieri not on piano but on harpsichord — a reflection, I always thought, of his aspirations to classical respectability — and Billy Butterfield on trumpet. It was a beautiful, hip, fresh group with which he recorded his composition Summit Ridge Drive, named for the street on which he lived in Los Angeles.

Shaw's theme song — every band had a theme song — seems in view of the century we have just been through and the one on which we are now embarked, quite appropriate. A composition of his own, and he was a very good composer when he bothered to do it, Nightmare was a stark piece consisting of a four-note chromatic ostinato over a pedal point and gloomy tom-tom figure, joined by a falling major third in which the clarinet plays lead to trumpets in straight mutes. It screams a kind of shrill terror, a Dostoevskian vision of the world, a clairvoyant look into imminent horrors. "Guernica" Artie said of it, and it did indeed have something of the Picasso mural of the German bombing of that Spanish town.

Nightmare, writer and cornetist Richard Sudhalter wrote in a liner note, "is a keening, almost cantorial melody in A minor, as different musically from the theme songs of his band-leading colleagues as Shaw was different from them personally and temperamentally."

Certainly it was no promise of romance, no Moonlight Serenade or Getting Sentimental Over You."And no Let's Dance" Artie added in pointed reference to Goodman. Nat Hentoff thinks he recalls Shaw telling him that it was based on an actual cantorian theme.

If you listen to a lot of Shaw's records at one sitting, you find that a powerful

general sadness suffuses them.

Artie told me, "My career as a serious dedicated player of a musical instrument really came to an end in 1941, when the war started. I was playing a theater in Providence, Rhode Island. The manager of the theater asked me to make an announcement. I went out and asked all servicemen in the crowd to return immediately to their bases. It seemed as if two thirds of the audience got up and walked out. We hadn't realized how many people had been going into service. With the whole world in flames, playing Stardust seemed pretty pointless.

After the show I put out the word to the guys, two weeks notice."

He joined the Navy early in 1942 and formed a band. He was offered the rank of lieutenant commander but turned it down. "As soon as you took a commission," Artie said, "you got into another world."And he wanted to play for the enlisted men. Eventually Shaw was given the rank of chief petty officer, at first stationed at Newport, Rhode Island. He soon chafed under the easy assignment. He knew Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, and he pulled wires. An admiral said to him, "Son, you're the first man I've met who didn't want to stay here and hang onto the grass roots. Where do you want to go?"

"Where's the Navy?" Artie said.

"In the South Pacific," the admiral said.

"And that's where I want to go," Artie said.

Glenn Miller joined the Army Air Corps and became a captain, then major, and went to England, to broadcast to the troops on the BBC from somewhere outside London. Shaw spoke of that too with a certain disdain. Artie took his men, designated Band 501 by the Navy, to the Pacific. There were a few mementoes of those days in his house, including a bullet-torn Japanese battle flag inscribed to him by Admiral Halsey; a model of a P-38 fighter made from brass shell casings by Seabees, who gave it to him; and, on the wall of the landing of the stairs, a painting done by a wartime artist for Life magazine showing Artie playing his clarinet in front of the band for troops on Guadalcanal. The background is a wall of jungle. In the picture Artie is wearing a black Navy tie tucked into the front of his shirt. This detail bugged him. "Halsey had banned ties," he said. "No tie. That was the uniform of the day." But there is something else that is somehow off. Artists rarely portray musicians accurately, and the stance of the figure in the painting wasn't quite right.

The band was in the South Pacific from mid-1942 until late 1943. It played in forward areas, some still harboring snipers, at times being bombed almost nightly. Once, with all its members under ponchos, it played for thousands of young paratroopers, themselves under ponchos and stretched up the slope of a hill in pounding tropical rain. When the band finally came home, the men were exhausted, depleted by what they had seen and by disease. Several of its members were immediately given medical discharges. "Davey Tough was just a ghost," Artie said. An exploding shell or grenade had damaged one of Artie's ear drums, and he was forever after that deaf in one ear. And he had been having crippling migraine headaches. When the Navy learned of this, he too was discharged.

The Shaw navy band continued without him, however. Its direction was assumed by Sam Donahue, who led it through 1944 until the war ended in 1945. Donahue commanded enormous respect among musicians and the band became a big success throughout Britain because of its BBC broadcasts. That Shaw band was never recorded, alas, but the band under Donahue was, and you can judge it for yourself through records on the doughty little Scottish Hep label, owned and operated by Alastair Robertson.

After leaving the navy, Shaw formed a new and excellent civilian band. It had a "modern" rhythm section with Dodo Marmarosa on piano, reflected the influences of bebop, and had superb charts by Ray Conniff. It recorded Lady Day, 'Swonderful, and Jumpin 'on theMerry-Go-Round. And then he abandoned that band too.

After that Shaw began working on classical pieces and played a concert with the National Symphony Orchestra in February 1949. The program included works by Ravel, Kabalesky, Debussy, Milhaud, Debussy, Granados, and Shostakovitch. They were recorded on the Columbia label with Walter Hendel conducting, and some of them are also available, along with some Grammercy Five tracks, on the Hep label, already mentioned, in a CD called The Artistry of Artie Shaw.

Shaw had one more important big band, the 1949 band that contained Herbie Steward, Frank Sokolow, Al Cohn, Zoot Sims, and Danny Bank, saxophones, Don Fagerquist in the trumpets, and Jimmy Raney, guitar, among others. Its writers included Johnny Mandel, Tadd Dameron, Gene Roland, Ray Conniff, George Russell, and Eddie Sauter. It was an advanced and adventurous band. Its only recordings were for Thesaurus Transcriptions, and it never found a large audience, but some of the material was released on CD by MusicMasters in 1990.

After that Artie put together — almost contemptuously, it would seem — a band that played the hits of the day. To his dismay, he claimed — then why did he do it, if he hadn't expected this? — it was a success. He folded that band in 1950. Senator Joseph McCarthy was running around like a rabid dog, causing heartache and heart attacks and leaving a trail of blighted lives. McCarthy told at least one journalist I know that he was going to be the first Catholic president of the United States. And he obviously didn't care whom he killed in pursuit of this ambition. This political performance contributed to Artie's disgust with the public and its manipulators. After playing some Gramercy Five gigs with Tal Farlow and Hank Jones and recording the group in 1954, he quit playing completely. He moved to Spain, there to finish his second book, I Love You, I Hate You, Drop Dead, short works of fiction whose acerbic title and content reflected his state of mind at the time. He admitted once to my wife that he went to Spain because he was frightened.

After he returned to the United States in 1960, he tried his hand at several things. He started, of all things, a rifle range and gun-manufacturing business. At one point he set out to become a marksman and got so good that he placed fourth in national competition. He established a film-distribution company. It was while he had this company that I first met him.

That would have been about 1966. When I encountered him again in California, in 1981, I found him changed — still a dominating talker, to be sure, but somehow more accessible. And witty. He was living alone in the house at Newbury Park with his books, a typewriter, a big friendly English sheepdog named Chester Chaucer, and a Hindsberg grand piano at which he would occasionally sit in solitary musing —"I've done some stupid things in my life," he said — playing Debussy or Scriabin. Now and then he would have friends in for dinner and, to judge by his protestations, he finally had his life in the rational control he had so assiduously sought to impose on it. But a certain loneliness, like a fine gray rain, seemed to have come over him. He never said so, and I never asked, but I could sense it.

He was teaching a course at Oxnard College not so much about music as esthetics in general. At the end of it, he asked the class if they had any questions. A young man stood up and said, "I play three instruments, piano, tenor, and bass."

"You've got a problem right there," Artie said. "What do you consider your primary instrument?"

"Bass, I guess."

"Because you can get away with more on bass, right? People can't hear pitch that well down in those registers. But what's your question?"

"I hate to practice," the young man said.

"Is that a question?"

"Well, yeah."

"Practicing goes with the territory, man. But I still don't know what the question is."

"What do I do about it?"

"Quit playing," Artie said.

I swung off California Highway 101 and wove through the winding streets to Artie's house, which, at the end of a short lane lined by oleanders, is hidden from the street.

I rang his bell, which had a small sign beside it: This is a writer's home. Do not ring without good reason. As he opened the door he said, "Hey, man, I got a book you should read."

"What's it called?"

"The Aquarian Conspiracy"

"Just read it." Remembering it now, it seems filled with the cardinal sin of political optimism.

"Well, that takes care of that."

"What else have you been reading?" I said as we settled in chairs in the big book-lined room on the second floor of the house.