© -Steven Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

I took a break from Jazz some time in the early 1970’s. I didn’t like where the music was going at the time so I decided to check out for awhile.

Many of the independent Jazz record labels were gone including Pacific Jazz [Dick Bock], Contemporary [Lester Koenig] on the Left Coast and Blue Note [without Alfred Lion] and Riverside [Orrin Keepnews] in The Big Apple.

The conglomerates hadn’t quite made their mark - Columbia was not as yet Sony, The Universal Music Group was still on the horizon, Warner-Elektra-Atlantic was still a decade or so away and EMI was still primarily a British recording and electronic corporation and not as yet a multinational amalgamation.

I got back into the music in the mid and late 1980s largely because of the recorded convenience of the compact disc and the huge LP reissue campaign that was characteristic of the nascent period of the digital music revolution. [Ironically, it was this very digitalization that brought into full swing the flurry of consolidations that resulted in the recorded music conglomerates.]

One day, while searching around a music store not too far from my office in San Francisco during a lunch hour break, I notice the name of an “old friend” on some discs released on the Landmark label.

Orrin Keepnews, the producer of so many legendary recordings for Riverside Records was back in business.

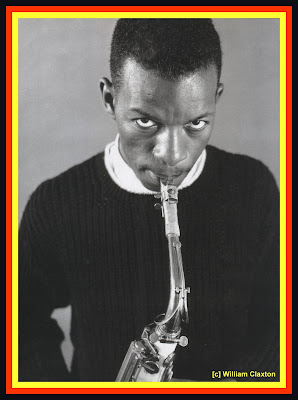

The discs in question were by Ralph Moore, a young tenor saxophone player, and they were entitled Images [Landmark LCD-1520-2] and Furthermore [Landmark 1526-2], respectively. [Perhaps “Furthermore” should have been titled “Further Moore” for those who enjoys puns?!]

Moore’s tenor sax was joined by Terence Blanchard’s trumpet on the former and Roy Hargrove’s trumpet on the latter and both are supported by a superb rhythm section of Benny Green on piano, Peter Washington on bass and Kenny Washington on drums.

I knew hardly anything about any of these musicians at the time but my ears told me that they were the real deal.

Speaking of “ears” [and eyes], in order to better familiarize myself with both the musicians and the music on these recordings I relied heavily on the following insert notes for each of these recordings.

Images [Landmark LCD-1520-2] - Stuart Troup [New York Newsday]

“A great musician is distinguished by his ears as well as his chops. And Ralph Moore, at 32, has obviously heard, absorbed, and assimilated the rewarding grit of jazz— and embroidered it with singular intensity.

He has gained acceptance from such bandleaders as J.J.Johnson, Freddie Hubbard, Roy Haynes, and Horace Silver. But even more impressive than those credentials is the convincing evidence we have right here in these recordings.

Moore is London-born, where "my mother got me interested in playing, at the age of 14. I was playing trumpet at first, but my teacher had a tenor sax and I liked the way it looked. It turned me on." A year later, Ralph emigrated to central California to live with his American father. "The music program at the high school included a jazz band," he says. "And then I spent a couple of years at the Berklee School of Music in Boston. Early on, I listened to Stanley Turrentine, Sonny Stitt, and Charlie Parker. Then all of a sudden it was Coltrane."

He needn't have confessed; the evidence is clear.

When Moore reached New York, he was quickly found and nurtured by Haynes, then Silver, and moved easily into the company of Hubbard, the Mingus Dynasty Band, and orchestras led by Dizzy Gillespie and Gene Harris. More recently he has taken part in J.J.Johnson's return to full-scale jazz activity.

What Ralph now brings to Images is exactly what all of the above found in him: a sense of adventure, understanding, and innovation. There is one important addition; as his own leader, he has been able to pick the repertoire and the sidemen of his choice. The compositions are divided between newer material and some unhackneyed, overlooked gems from the earlier years of the modern jazz tradition. In particular, his use of works by tenor players Hank Mobley and Joe Henderson, plus a personal tribute to John Coltrane, makes clear one meaning of the album title. And his accompanying musicians form a support system that provides a resilient cushion and complementary strengths.

The basic unit of pianist Benny Green, bassist Peter Washington, and drummer Kenny Washington meshes solidly from the opener, a Moore original called Freeway.This is one of four cuts calling on Terence Blanchard, a supple, often poignant trumpeter who has earned his high visibility during the past few years. He and Ralph play unison passages on the head, a modal excursion through 16 bars, with a 12-measure bridge.

Moore gently nudges trombonist Johnson's haunting ballad, Enigma, with his melancholy tone, and caps it with the coda that Miles Davis played on the original record. "It's sort of my tribute to J.J., with whom I worked quite a bit during 1988," he says.

Episode from a Village Dance is a tune by Donald Brown, one of several impressive newer pianist/composers. It is underpinned by infectious Latin rhythms—including deft conga playing by Victor See-Yuen. Moore's tenor is warm; Blanchard's trumpet is searing. When producer Orrin Keepnews asked Brown to explain the unusual title, "he said he was trying to get the feeling of a carnival in a South American village, and this piece is just one aspect of what's going on there."

Ralph supplies a plaintive but tension-free edge to Morning Star, a medium-tempo tune by Rodgers Grant (who spent a number of years playing piano and writing solidly for Mongo Santamaria). Moore and Green solo with warmth over the impeccable foundation supplied by drummer Washington.

This I Dig of You, a Hank Mobley original, evokes the spirit of hard bop.The piece has remained undeservedly ignored since the late saxophonist recorded it on Blue Note years ago. "Kenny and Peter really hooked up well throughout, but especially on this one," notes Moore. "Kenny doesn't just play drums, he plays music. He breathes." Keepnews had a comment of his own to add about these two players: "I told them that unrelated bass and drum teams with the same last name was an important jazz tradition"—the reference, of course, is to Sam Jones and Philly Joe.

Blues for John, as indicated, is dedicated to Coltrane. "When I was writing the head," the young tenor player says, "I was thinking about Trane." It's a fine example of Ralph's adventurousness. And, as he points out: "Benny plays his brains out."

Moore thoroughly explores Joe Henderson's Punjab, stamping the punchy, percussive melody with his own imprimatur. "We played it a little faster than Joe did"— but with no less imagination.

Elmo Hope, the great bop pianist who died in 1967 at age 43, was responsible for the closer, One Second, Please, an unusual, even arch, piece on which Ralph displays a forceful, almost swaggering attack.

It's all powerful evidence that those of us concerned by the passing, in recent years, of such heavyweights as Sonny Stitt, Budd Johnson, Lockjaw Davis, Zoot Sims and Al Cohn, and Charlie Rouse, can at least feel confident about the future of jazz tenor.”

Furthermore [Landmark 1526-2] - Orrin Keepnews

“One of the greatest satisfactions in my line of work has come from observing that magic sequence I sometimes think of as "crossing the line." Occasionally it is swift, but more often it sneaks up gradually but inevitably, as a musician you're working with breaks through the invisible, intangible (but quite real) barrier tha distinguishes the merely "promising" from the accepted, the interesting from the important. Calendar age has nothing to do with it: some achieve this status quite early, while others may spend a lifetime waiting. Musical maturity is very relevant; the event is best described — if you'll forgive the cliche — as separating the men from the boys.

By the middle of the year in which these numbers were recorded, RALPH MOORE had crossed the line. There was no single blinding flash to mark the occasion, but there were many signposts along the way:

Still in his early 30s, Moore has worked with a dazzling array of leaders: Horace Silver, Roy Haynes, Dizzy Gillespie, Freddie Hubbard, J. J. Johnson—which sounds like (and is) great training, but led one critic to wonder if he weren't destined to be "a sideman for everyone." But that same writer, Peter Watrous, reviewing Ralph's previous Landmark album in Musician magazine, pronounced it "a stunning leap forward" and called him "an individual voice."

On the first Sunday in 1990, the Calendar section of the Los Angeles Times devoted a page to five acoustic jazz artists "most likely to have an impact. . . in the coming decade" and included Moore, citing his Landmark debut as "one of the most rewarding and listenable jazz releases in recent memory."

Last fall's Phillip Morris-sponsored "Superband" world tour, by an almost entirely veteran orchestra with only three young players, had Ralph as one of two tenors, affording him the honor and pleasure of teaming with all-timer James Moody.

When teenage trumpeter Roy Hargrove (who plays an important role on this album) made an early sideman appearance at New York's legendary Village Vanguard, it was in a quintet led by Moore: Roy's management were looking to Ralph as the comparative veteran to introduce the newcomer — an unaccustomed task, but one he might as well get used to.

Following these and other examples, it was hardly any kind of surprise when the 1990 critics polls of both Down Beat and JazzTimes magazines agreed on him as tenor saxophone winner in the category known, respectively, as "Talent Deserving Wider Recognition" and "Emerging Talent." No surprise, but a very fitting pair of exclamation points for a sentence such as: Ralph Moore has arrived!!

A good deal of documentation for all this is to be heard on the seven selections here: the power and imagination, the swiftly-growing command and assurance. Ralph has now taken steps to assemble a regular working group of his own, and this could well be its permanent rhythm section (with either drummer). Up to now, he has worked with them as often as possible. When a schedule conflict made Kenny Washington (who had combined superbly with Peter Washington and Benny Green on Ralph's previous Landmark recording) miss the Vanguard week, Victor Lewis had been called in. When Victor was unavailable for the first of these two sessions, Kenny stepped in! There clearly was no problem either way in achieving a fully-meshed unit.

On four selections, the addition of Roy Hargrove makes it the familiar post-bop trumpet/tenor front line, but actually Roy makes it anything but routine. There is much empathy between the two horns, and the younger man has a whole lot to add here. To be strictly accurate, Hargrove can no longer be called a teenager, since he has by now turned 20, but he is very likely to be recognized as part of the great tradition of early-blooming trumpet players.

A well-balanced repertoire combines three examples of Ralph's writing with contributions from Hargrove and Green and adds a soulful version of Neal Hefti's Girl Talk and an impressive quartet treatment of Thelonious Monk's seldom-attempted Monk's Dream. Altogether a proper celebration of the solid status of Ralph Moore.”

I put together the following video tribute to Ralph and “the boys in the band” using the Hank Mobley This I Dig of You because I have always dug the tune and because the harmony that Terence Blanchard plays is in the lower register which is sadly not often heard on the instrument.

I also played with a band run by trumpeter Jimmy Zito off and on for about a year. He was a fine player and a good friend of mine whose claim to fame was that he had been married to June Haver, a big movie star at the time. I remember when the band was playing at a dance hall in San Francisco and every night, after work, we would go to the Filmore district to jam in after-hours clubs. One night we were packing up to go home and a little boy, no more than twelve years old, asked me if I wanted to buy a saxophone and a clarinet. I looked at them and they were both better than mine, and although I was a little wary, I took a chance and paid him the $75 he was asking. The next day I met Bob Kesterton, who was a friend of Charlie Parker's and had played on the 1947 "Lover Man" session with Howard McGhee. I told him that I had bought a sax and clarinet early that morning and he said, "I'm working with a guy who lost his last night!" We both realized what had happened and he said, "If you like, I won't say anything," but I couldn't do that, so Bob gave me the guy's telephone number and it turned out to be Paul Desmond, who confirmed they were his instruments. He came to my hotel to collect them, and this was the first time we had ever met. I mentioned the $75 I had paid, which I would like to get back, and he promised to talk to his insurance company. When he phoned me he said, "They say I shouldn't pay you, but instead I should lodge a police complaint against you!" Luckily he didn't, but a few years later I saw him in New York when he was with Dave Brubeck and I didn't have too much money. He said, "I never did give you that $75," and he paid me, which was nice. I really needed it because I was working out my union card and had very little work.

I also played with a band run by trumpeter Jimmy Zito off and on for about a year. He was a fine player and a good friend of mine whose claim to fame was that he had been married to June Haver, a big movie star at the time. I remember when the band was playing at a dance hall in San Francisco and every night, after work, we would go to the Filmore district to jam in after-hours clubs. One night we were packing up to go home and a little boy, no more than twelve years old, asked me if I wanted to buy a saxophone and a clarinet. I looked at them and they were both better than mine, and although I was a little wary, I took a chance and paid him the $75 he was asking. The next day I met Bob Kesterton, who was a friend of Charlie Parker's and had played on the 1947 "Lover Man" session with Howard McGhee. I told him that I had bought a sax and clarinet early that morning and he said, "I'm working with a guy who lost his last night!" We both realized what had happened and he said, "If you like, I won't say anything," but I couldn't do that, so Bob gave me the guy's telephone number and it turned out to be Paul Desmond, who confirmed they were his instruments. He came to my hotel to collect them, and this was the first time we had ever met. I mentioned the $75 I had paid, which I would like to get back, and he promised to talk to his insurance company. When he phoned me he said, "They say I shouldn't pay you, but instead I should lodge a police complaint against you!" Luckily he didn't, but a few years later I saw him in New York when he was with Dave Brubeck and I didn't have too much money. He said, "I never did give you that $75," and he paid me, which was nice. I really needed it because I was working out my union card and had very little work. [In this 1950 photo of the Fina band taken at the Waldorf Astoria in New York Herb Geller is second from the right and Paul Desmond is fourth from the right]

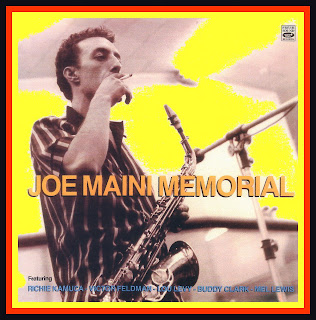

[In this 1950 photo of the Fina band taken at the Waldorf Astoria in New York Herb Geller is second from the right and Paul Desmond is fourth from the right] In the late forties, Joe Maini and Jimmy Knepper lived in an apartment in New York which became famous for all-night jam sessions. We were all friends from L.A., and Jimmy and I had grown up together, as we were both born there. Joe was born in Rhode Island but moved out with his family when he was about fourteen years old. About a year or two after the Jack Fina trip, I had returned to New York and they had an apartment on the corner of 136th Street and Broadway. It was like a twenty-four-hour jam session, where you could visit at any time and there was always music being played, together with all kinds of nefarious activities going on. The music was wild, and as I could play a little piano, at least 1 knew the right chords, I would very often end up as the pianist. Once, though, I remember playing "Out of Nowhere" on the saxophone when Charlie Parker walked in, and of course I froze. I turned to the guys and said, "I can't think of anything interesting to play!" Everybody used to go there - Dizzy, Joe Albany, Max Roach, Miles, Warne Marsh, Gerry Mulligan. In fact, if you went to Joe's, you would meet the entire "who's who" of jazz. They had two beds in the middle of the room, and sometimes you would be blowing, and Joe or Jimmy would say, "I've been up for about four days now. I'm going to bed." They would go to sleep and snore and everybody else would still be playing.

In the late forties, Joe Maini and Jimmy Knepper lived in an apartment in New York which became famous for all-night jam sessions. We were all friends from L.A., and Jimmy and I had grown up together, as we were both born there. Joe was born in Rhode Island but moved out with his family when he was about fourteen years old. About a year or two after the Jack Fina trip, I had returned to New York and they had an apartment on the corner of 136th Street and Broadway. It was like a twenty-four-hour jam session, where you could visit at any time and there was always music being played, together with all kinds of nefarious activities going on. The music was wild, and as I could play a little piano, at least 1 knew the right chords, I would very often end up as the pianist. Once, though, I remember playing "Out of Nowhere" on the saxophone when Charlie Parker walked in, and of course I froze. I turned to the guys and said, "I can't think of anything interesting to play!" Everybody used to go there - Dizzy, Joe Albany, Max Roach, Miles, Warne Marsh, Gerry Mulligan. In fact, if you went to Joe's, you would meet the entire "who's who" of jazz. They had two beds in the middle of the room, and sometimes you would be blowing, and Joe or Jimmy would say, "I've been up for about four days now. I'm going to bed." They would go to sleep and snore and everybody else would still be playing. Anyway, six months to the day after applying, I got my union card and was offered three jobs. I took the one with Jerry Wald because he had a good library of At Cohn arrangements and At was to rehearse the band. Jerry played clarinet like Artie Shaw, though not nearly as well, and he wanted me to replace Gene Quill on lead alto, because they didn't get along and Gene didn't have a union card. The band was playing at the Arcadia Ballroom, where there was a strict Local 802 policy for tax reasons. Of course at first there was some resentment, because Gene was very popular with the guys and he was an excellent player, but quite soon I was accepted and everything was fine. Gene, though, was angry at me for taking his job. A couple of years later I had another unfortunate incident with him concerning a studio date with Nat Pierce. I was having dinner with Nat at his apartment, and he had to leave early for the recording. I had my alto with me, as I was going to a jam session, and about a half hour after he left, Nat telephoned to say Quill hadn't shown up and could I get down to the studio straight away. I took a cab, and as I arrived, another cab pulled up and Gene came running in. Nat was waiting and said, "Listen, Gene. Herb is going to do the date because whenever I use you, you're either late or you don't show up at all." Gene of course flipped out and said, "You can't do this" and told me that I was always taking his jobs. I felt bad and told Nat to use Gene, but he wouldn't change his mind, and naturally Gene was very bitter towards me and I can understand why. Many years later, after I moved to Germany, I heard that he was very ill. He had been badly beaten up, could never play again, and desperately needed money for his family. I sent him $100 and received a well-typed letter, signed in barely legible handwriting, "Thank you, Gene Quill." He was a wonderful player.

Anyway, six months to the day after applying, I got my union card and was offered three jobs. I took the one with Jerry Wald because he had a good library of At Cohn arrangements and At was to rehearse the band. Jerry played clarinet like Artie Shaw, though not nearly as well, and he wanted me to replace Gene Quill on lead alto, because they didn't get along and Gene didn't have a union card. The band was playing at the Arcadia Ballroom, where there was a strict Local 802 policy for tax reasons. Of course at first there was some resentment, because Gene was very popular with the guys and he was an excellent player, but quite soon I was accepted and everything was fine. Gene, though, was angry at me for taking his job. A couple of years later I had another unfortunate incident with him concerning a studio date with Nat Pierce. I was having dinner with Nat at his apartment, and he had to leave early for the recording. I had my alto with me, as I was going to a jam session, and about a half hour after he left, Nat telephoned to say Quill hadn't shown up and could I get down to the studio straight away. I took a cab, and as I arrived, another cab pulled up and Gene came running in. Nat was waiting and said, "Listen, Gene. Herb is going to do the date because whenever I use you, you're either late or you don't show up at all." Gene of course flipped out and said, "You can't do this" and told me that I was always taking his jobs. I felt bad and told Nat to use Gene, but he wouldn't change his mind, and naturally Gene was very bitter towards me and I can understand why. Many years later, after I moved to Germany, I heard that he was very ill. He had been badly beaten up, could never play again, and desperately needed money for his family. I sent him $100 and received a well-typed letter, signed in barely legible handwriting, "Thank you, Gene Quill." He was a wonderful player. Another fine altoist from that period was Dave Schildkraut, who was quite superb and was one of the greatest. I don't know what happened, but he just seemed to stop playing and started working for his father, who had a grocery store and didn't like jazz musicians. It was a sad situation because there was no drug or alcohol problem; he was just a nice Jewish boy from Brooklyn who played great alto and fantastic clarinet. He was very creative and original with his own sound, and he had made a recording with Miles. I never heard of him again, but he was one of the best saxophone players I knew, just sensational.'

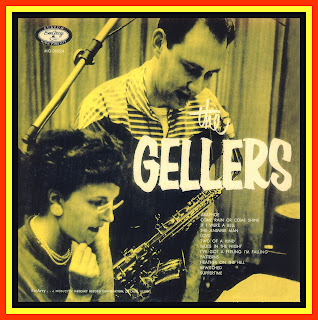

Another fine altoist from that period was Dave Schildkraut, who was quite superb and was one of the greatest. I don't know what happened, but he just seemed to stop playing and started working for his father, who had a grocery store and didn't like jazz musicians. It was a sad situation because there was no drug or alcohol problem; he was just a nice Jewish boy from Brooklyn who played great alto and fantastic clarinet. He was very creative and original with his own sound, and he had made a recording with Miles. I never heard of him again, but he was one of the best saxophone players I knew, just sensational.' Early in 1952 I married Lorraine Walsh, who was an excellent jazz pianist. She could play every tune in any key, tempo, or style, and she had a very rhythmic feel, so of course she was much in demand as an accompanist. I was with Jerry Wald at the time, but quite soon I had an offer to join Billy May, who was coming to the New York Paramount Theatre, which was very well paid. Willie Smith was the other alto, and to sit next to him was a great thrill for me. I was with Billy May for about five months, and when the band went back to L.A., I took Lorraine with me to meet my parents. We decided to stay, because suddenly L.A. was very promising. There was a lot of jazz going on and general recording activity, as this was the beginning of what the critics were calling West Coast Jazz.

Early in 1952 I married Lorraine Walsh, who was an excellent jazz pianist. She could play every tune in any key, tempo, or style, and she had a very rhythmic feel, so of course she was much in demand as an accompanist. I was with Jerry Wald at the time, but quite soon I had an offer to join Billy May, who was coming to the New York Paramount Theatre, which was very well paid. Willie Smith was the other alto, and to sit next to him was a great thrill for me. I was with Billy May for about five months, and when the band went back to L.A., I took Lorraine with me to meet my parents. We decided to stay, because suddenly L.A. was very promising. There was a lot of jazz going on and general recording activity, as this was the beginning of what the critics were calling West Coast Jazz. When I first arrived there, I sometimes worked in striptease clubs, because I knew "Night Train" and "Harlem Nocturne," which I suppose qualified me! Lenny Bruce was the comic at several clubs, and we got to know each other real well. He loved jazz music and jazz musicians, so we would hang out together, and sometimes Joe Maini and I would split a job. If I had a jazz gig, he would cover for me at the strip club, and vice versa. It was a wild scene, and all three of us were very close. Later on I worked with Lenny at an infamous burlesque club called Duffy's Gaiety near Santa Monica Boulevard. He was the M.C., his wife Honey Harlow was stripping, and I was the bandleader, with Lorraine on piano. We also had different drummers at various times, like Philly Joe Jones and Lawrence Marable. Philly Joe became very tight with Lenny, who taught him his Dracula routine, which Philly Joe recorded as "Blues for Dracula." During the drum solo, he did a monologue imitating Lenny imitating Bela Lugosi. Jack Sheldon was there every night, because Lenny was really infamous then, not quite a star yet, but "in" to the real hip people. Bob Hope, Hedy Lamarr, Ernie Kovacs, and a lot of movie people came, and I remember Bing Crosby's son Gary used to date the girls. Someone should write the story of Duffy's Gaiety, because every night was an adventure .

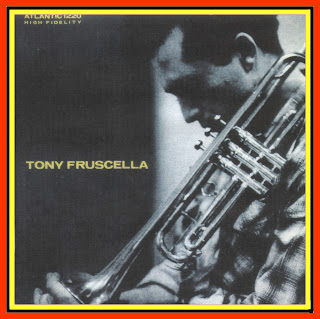

When I first arrived there, I sometimes worked in striptease clubs, because I knew "Night Train" and "Harlem Nocturne," which I suppose qualified me! Lenny Bruce was the comic at several clubs, and we got to know each other real well. He loved jazz music and jazz musicians, so we would hang out together, and sometimes Joe Maini and I would split a job. If I had a jazz gig, he would cover for me at the strip club, and vice versa. It was a wild scene, and all three of us were very close. Later on I worked with Lenny at an infamous burlesque club called Duffy's Gaiety near Santa Monica Boulevard. He was the M.C., his wife Honey Harlow was stripping, and I was the bandleader, with Lorraine on piano. We also had different drummers at various times, like Philly Joe Jones and Lawrence Marable. Philly Joe became very tight with Lenny, who taught him his Dracula routine, which Philly Joe recorded as "Blues for Dracula." During the drum solo, he did a monologue imitating Lenny imitating Bela Lugosi. Jack Sheldon was there every night, because Lenny was really infamous then, not quite a star yet, but "in" to the real hip people. Bob Hope, Hedy Lamarr, Ernie Kovacs, and a lot of movie people came, and I remember Bing Crosby's son Gary used to date the girls. Someone should write the story of Duffy's Gaiety, because every night was an adventure . I played a lot with Chet Baker, and we got along real well. We made an album together in 1953 with Bob Gordon and Jack Montrose, and despite what you hear, Chet could read music, although he was not a sight-reader. After playing the part through slowly a few times, he could play it perfectly. In fact, nobody could play it better. Early in 1953, when he and Gerry Mulligan were at the Haig, Gerry eloped with a waitress from the club and Chet asked for me, because he needed another horn in the quartet to keep working. We played for about three weeks, until Gerry got back from his honeymoon, by which time he was probably divorced already!

I played a lot with Chet Baker, and we got along real well. We made an album together in 1953 with Bob Gordon and Jack Montrose, and despite what you hear, Chet could read music, although he was not a sight-reader. After playing the part through slowly a few times, he could play it perfectly. In fact, nobody could play it better. Early in 1953, when he and Gerry Mulligan were at the Haig, Gerry eloped with a waitress from the club and Chet asked for me, because he needed another horn in the quartet to keep working. We played for about three weeks, until Gerry got back from his honeymoon, by which time he was probably divorced already! Bob Gordon was a wonderful baritone player who was just establishing himself when he was killed in an automobile accident. In 1988, when I was in New York for a recording session with Benny Carter, I met a young man who said, "You knew my stepfather, Bob Gordon." The youngster played alto, and he played very well. I saw Jack Montrose as recently as 1992 in Las Vegas, where he and his wife, who is a violinist, work in the shows. He is a dear friend and I like him very much personally, but jazz-wise, I don't know what happened. He is semi-retired now, but for a long time he was writing classical music. He studied the twelve-tone system and has written lots of twelve-tone music that will never be played, and he knows it will never be played. But he owns his own house, has a lovely wife, and they are O.K. in Vegas.

Bob Gordon was a wonderful baritone player who was just establishing himself when he was killed in an automobile accident. In 1988, when I was in New York for a recording session with Benny Carter, I met a young man who said, "You knew my stepfather, Bob Gordon." The youngster played alto, and he played very well. I saw Jack Montrose as recently as 1992 in Las Vegas, where he and his wife, who is a violinist, work in the shows. He is a dear friend and I like him very much personally, but jazz-wise, I don't know what happened. He is semi-retired now, but for a long time he was writing classical music. He studied the twelve-tone system and has written lots of twelve-tone music that will never be played, and he knows it will never be played. But he owns his own house, has a lovely wife, and they are O.K. in Vegas. In 1954, I recorded with Clifford Brown and Dinah Washington . We were all under contract to Mercury, who wanted to use several of their artists in a jam-session setting with a live audience, rather like "Jazz at the Philharmonic." The highlight for me was playing with Clifford, who was a marvelous, extraordinary human being and musician. He was one of the nicest people you could meet, and a complete "natural" who could play anything. Rather like Chet, he could pick up any instrument and fool around for a while, and then play it real well. I remember once when Max Roach, who had been playing at the Lighthouse with Lorraine, decided to have a party. A lot of jazz people were there, and everyone was smoking and drinking except Brownie, who didn't smoke or drink at all. He never swore and was just a lovely person: clean-cut, unassuming, and modest. Anyway, Max had been carrying a set of vibes with him everywhere he went, but he never touched them, just set them in a comer. Clifford started fooling around with them, and in about an hour or so he was playing with four mallets. Max was furious. He'd had them for years and couldn't even play a scale, but Clifford learned to play them while everyone was getting drunk. He was such a loss, because there is nobody today to match him. I mean Freddie Hubbard is wonderful, Wynton Marsalis can play, but I don't hear in anyone what I heard in Brownie. His sound was so beautiful and soulful, with such a sparkling way of playing.

In 1954, I recorded with Clifford Brown and Dinah Washington . We were all under contract to Mercury, who wanted to use several of their artists in a jam-session setting with a live audience, rather like "Jazz at the Philharmonic." The highlight for me was playing with Clifford, who was a marvelous, extraordinary human being and musician. He was one of the nicest people you could meet, and a complete "natural" who could play anything. Rather like Chet, he could pick up any instrument and fool around for a while, and then play it real well. I remember once when Max Roach, who had been playing at the Lighthouse with Lorraine, decided to have a party. A lot of jazz people were there, and everyone was smoking and drinking except Brownie, who didn't smoke or drink at all. He never swore and was just a lovely person: clean-cut, unassuming, and modest. Anyway, Max had been carrying a set of vibes with him everywhere he went, but he never touched them, just set them in a comer. Clifford started fooling around with them, and in about an hour or so he was playing with four mallets. Max was furious. He'd had them for years and couldn't even play a scale, but Clifford learned to play them while everyone was getting drunk. He was such a loss, because there is nobody today to match him. I mean Freddie Hubbard is wonderful, Wynton Marsalis can play, but I don't hear in anyone what I heard in Brownie. His sound was so beautiful and soulful, with such a sparkling way of playing. One of the records Lorraine and I made together was with Ziggy Vines, who is probably almost forgotten today. He was even obscure at the time, and Leonard Feather, who did the sleeve-note for the album, thought he was actually a pseudonym for Georgie Auld, but he really did exist. He came from a very rich family in Philadelphia and had a natural, unbelievable talent. He was a legend in New York when I first met him, although he never seemed to have a horn, but he sure could play. One day in 1955, out of a clear blue sky he telephoned, saying, "It's me, Ziggy Vines. I'm in L.A., and I need some money. Have you got any work for me?" Lorraine and I were just about to do a quintet album with Conte Candoli, and I thought it would be a good idea to rewrite it for a sextet using Ziggy. Two days before the date, he phoned again and said, "I need a horn, a mouthpiece, some reeds, and a place to stay." I lent him my tenor, bought him some reeds and a mouthpiece, and arranged for him to move in with Lorraine and me. Anyway, he came to the date, and although he hadn't touched a saxophone for quite a time, he played just great because he was a natural, swinging musician. I don't know what happened to him after that, but there is a rumor that he was taped playing with Clifford Brown the night before Brownie was killed in Philadelphia.

One of the records Lorraine and I made together was with Ziggy Vines, who is probably almost forgotten today. He was even obscure at the time, and Leonard Feather, who did the sleeve-note for the album, thought he was actually a pseudonym for Georgie Auld, but he really did exist. He came from a very rich family in Philadelphia and had a natural, unbelievable talent. He was a legend in New York when I first met him, although he never seemed to have a horn, but he sure could play. One day in 1955, out of a clear blue sky he telephoned, saying, "It's me, Ziggy Vines. I'm in L.A., and I need some money. Have you got any work for me?" Lorraine and I were just about to do a quintet album with Conte Candoli, and I thought it would be a good idea to rewrite it for a sextet using Ziggy. Two days before the date, he phoned again and said, "I need a horn, a mouthpiece, some reeds, and a place to stay." I lent him my tenor, bought him some reeds and a mouthpiece, and arranged for him to move in with Lorraine and me. Anyway, he came to the date, and although he hadn't touched a saxophone for quite a time, he played just great because he was a natural, swinging musician. I don't know what happened to him after that, but there is a rumor that he was taped playing with Clifford Brown the night before Brownie was killed in Philadelphia. In the late fifties Don Cherry stayed at my house for a while, when he and his wife were evicted from their apartment, but I never really cared for his music. He was playing in a "free" way even then, because he couldn't play normally. People said that he and Ornette Coleman could play changes, but I don't believe it, man. I heard Ornette's recording of "Embraceable You," and it's a laugh. I'm sorry, but that's not "Embraceable You." I mean, put him to the test - the Emperor has no clothes. They both played some nice, folksy, rather primitive, naive-sounding things that had a certain charm, but I couldn't take their approach seriously, even to this day. Ornette came to my house once because he wanted to have his music corrected. He showed me his tunes, and they were a catastrophe, because the bar lines were in the wrong place and there were no chord symbols. He took his saxophone out, and I notated what he played. I asked him what chord he was using, and he blew the arpeggio of a G chord thinking it was a B minor. He just didn't know anything about chords. Years later he was talking about George Russell's Lydian Concept, so I asked him if he had found out the difference between B minor and G yet! I liked Omette as a person, and he did a sweet thing after my wife died. He wrote a piece which I think he called "Lorraine," and I was very touched by that.' Some of his tunes have haunting melodies, but I don't really care for that type of playing. I can play "free," but it's just a lot of meandering about, and anyone can meander; you buy an instrument and make a record in two weeks!

In the late fifties Don Cherry stayed at my house for a while, when he and his wife were evicted from their apartment, but I never really cared for his music. He was playing in a "free" way even then, because he couldn't play normally. People said that he and Ornette Coleman could play changes, but I don't believe it, man. I heard Ornette's recording of "Embraceable You," and it's a laugh. I'm sorry, but that's not "Embraceable You." I mean, put him to the test - the Emperor has no clothes. They both played some nice, folksy, rather primitive, naive-sounding things that had a certain charm, but I couldn't take their approach seriously, even to this day. Ornette came to my house once because he wanted to have his music corrected. He showed me his tunes, and they were a catastrophe, because the bar lines were in the wrong place and there were no chord symbols. He took his saxophone out, and I notated what he played. I asked him what chord he was using, and he blew the arpeggio of a G chord thinking it was a B minor. He just didn't know anything about chords. Years later he was talking about George Russell's Lydian Concept, so I asked him if he had found out the difference between B minor and G yet! I liked Omette as a person, and he did a sweet thing after my wife died. He wrote a piece which I think he called "Lorraine," and I was very touched by that.' Some of his tunes have haunting melodies, but I don't really care for that type of playing. I can play "free," but it's just a lot of meandering about, and anyone can meander; you buy an instrument and make a record in two weeks! Charlie Mariano and Art Pepper were very active in California during the fifties. Charlie and I were always friends, and I took his place with Shelly Manne's group when he wanted to go home to Boston. I have always liked the way he plays, and among my contemporaries, I would say that he is my favorite. He is very original and plays with a lot of soul in a completely different style to me, which is great. I don't bother him, and he doesn't bother me! Regarding Art Pepper, I have to say that there was never any love lost between us, or between Art and Joe Maini, or Art and anyone else for that matter, because nobody liked him personally. Musically it's a matter of taste, but I was never much of a fan, to tell you the truth. He played well, but I don't think there was any great content, and Joe was of the same opinion.

Charlie Mariano and Art Pepper were very active in California during the fifties. Charlie and I were always friends, and I took his place with Shelly Manne's group when he wanted to go home to Boston. I have always liked the way he plays, and among my contemporaries, I would say that he is my favorite. He is very original and plays with a lot of soul in a completely different style to me, which is great. I don't bother him, and he doesn't bother me! Regarding Art Pepper, I have to say that there was never any love lost between us, or between Art and Joe Maini, or Art and anyone else for that matter, because nobody liked him personally. Musically it's a matter of taste, but I was never much of a fan, to tell you the truth. He played well, but I don't think there was any great content, and Joe was of the same opinion. Of course I was emotionally distraught with the death of my wife and the adoption of my daughter because I couldn't provide a proper home for her, but I kept busy. One night I had a call from a lady who said that a friend of mine was in town and wanted to surprise me at the club where I was playing, and would I give her the address? I was working in a burlesque club on Santa Monica Boulevard called the Pink Pussycat. Later that night, I was playing "Night Train" or some boogie-woogie thing with my eyes closed, and I felt a hand on my shoulder. It was Stan Getz, a very old and dear friend who I loved very much. Just like Benny Goodman, I've heard a lot of terrible stories of what he did to other people, but to me, he was just a great human being. During the intermission we talked, and he suggested that I go to Europe for a while. I had already given some thought to that, because L.A. had too many memories, and Stan said he would contact the owner of the Montmarte club in Copenhagen to get me some work while I decided what to do, and that's how I came to leave the U.S.A.

Of course I was emotionally distraught with the death of my wife and the adoption of my daughter because I couldn't provide a proper home for her, but I kept busy. One night I had a call from a lady who said that a friend of mine was in town and wanted to surprise me at the club where I was playing, and would I give her the address? I was working in a burlesque club on Santa Monica Boulevard called the Pink Pussycat. Later that night, I was playing "Night Train" or some boogie-woogie thing with my eyes closed, and I felt a hand on my shoulder. It was Stan Getz, a very old and dear friend who I loved very much. Just like Benny Goodman, I've heard a lot of terrible stories of what he did to other people, but to me, he was just a great human being. During the intermission we talked, and he suggested that I go to Europe for a while. I had already given some thought to that, because L.A. had too many memories, and Stan said he would contact the owner of the Montmarte club in Copenhagen to get me some work while I decided what to do, and that's how I came to leave the U.S.A. One of the first people I met in Europe was Brew Moore, who I was very fond of. I remember during the Berlin Jazz Festival they had a theme called -'The History of the Tenor Sax," and Brew represented the Lester Young school. All the guys got completely drunk after the concert, and the next morning he called me over to his hotel in a panic. Apparently he had been so drunk that he had left his horn, coat, and wallet in a taxicab and had thrown up all over his clothes. He had sent his suit out to be cleaned, and when I arrived, he was sitting in his underwear. He said, "Herb, I can't speak German and nobody here speaks any English. I've lost my horn; I don't have my passport, and I can't get out of Berlin without it. What am I going to do?" Luckily the story had a happy ending because he sobered up, recovered everything, and got out of Berlin alive! Do you know the sad story of how he died? He inherited a lot of money from his grandfather I think, gave a huge party to celebrate and, in the middle of everything, fell down some stairs and died of a broken neck. It could only happen to a jazz musician. He was a wonderful, natural player, like Zoot. It was strictly talent and intuition with both of them.

One of the first people I met in Europe was Brew Moore, who I was very fond of. I remember during the Berlin Jazz Festival they had a theme called -'The History of the Tenor Sax," and Brew represented the Lester Young school. All the guys got completely drunk after the concert, and the next morning he called me over to his hotel in a panic. Apparently he had been so drunk that he had left his horn, coat, and wallet in a taxicab and had thrown up all over his clothes. He had sent his suit out to be cleaned, and when I arrived, he was sitting in his underwear. He said, "Herb, I can't speak German and nobody here speaks any English. I've lost my horn; I don't have my passport, and I can't get out of Berlin without it. What am I going to do?" Luckily the story had a happy ending because he sobered up, recovered everything, and got out of Berlin alive! Do you know the sad story of how he died? He inherited a lot of money from his grandfather I think, gave a huge party to celebrate and, in the middle of everything, fell down some stairs and died of a broken neck. It could only happen to a jazz musician. He was a wonderful, natural player, like Zoot. It was strictly talent and intuition with both of them. Getting back to Stan Getz, we first met in L.A. in 1946 or '47. He had left Benny Goodman in New York, and he was waiting to get his union card, so he didn't have too much work or money, and of course he had his first wife, Beverly, and a child to support. We were both playing tenor in a band led by Dick Pierce. Stan played lead and I was on second, although I never really was a tenor player, but I was so fascinated by the way he played, I asked him for a lesson to show me some of the things he was doing. I had never heard a style like that because at that time, when I played tenor, I had Ben Webster and Don Byas in mind, but Stan had a different approach. I spent several hours at his house, and he showed me many things to practice, and at the end of the lesson, he gave me a mouthpiece, saying, "That will help you get the sound you want." Now Stan didn't have any money, and I wanted to pay him for the lesson, because I had learned a lot, but he wouldn't take anything; he was just great.

Getting back to Stan Getz, we first met in L.A. in 1946 or '47. He had left Benny Goodman in New York, and he was waiting to get his union card, so he didn't have too much work or money, and of course he had his first wife, Beverly, and a child to support. We were both playing tenor in a band led by Dick Pierce. Stan played lead and I was on second, although I never really was a tenor player, but I was so fascinated by the way he played, I asked him for a lesson to show me some of the things he was doing. I had never heard a style like that because at that time, when I played tenor, I had Ben Webster and Don Byas in mind, but Stan had a different approach. I spent several hours at his house, and he showed me many things to practice, and at the end of the lesson, he gave me a mouthpiece, saying, "That will help you get the sound you want." Now Stan didn't have any money, and I wanted to pay him for the lesson, because I had learned a lot, but he wouldn't take anything; he was just great.

I have just retired after twenty-eight years playing for the North German Radio Orchestra, but I like to keep busy, because I'm a workaholic. I teach a lot and I'm a professor at two universities, and I have also been involved in two musicals. The first one concerns all these stories I have been telling you. About five years ago, a friend told me that I should write my memoirs, and I said that if I ever did, it would be in the form of a musical. Soon afterwards I heard that Joe Albany had died, and he was a very important figure in my life. He was the first avant-garde jazz pianist, if you like, playing across bar lines ignoring strict tempo, and playing wild chords. He was very emotional and sometimes played poorly, but when he was "on," it was just fantastic. The Herald Tribune, however, gave him about three lines. Soon afterwards Chet Baker and Al Cohn died, and I was very touched. I wrote songs with lyrics for all three, and I thought, "What am I going to do with these songs?" That was when I decided to turn my memoirs into a musical, and I put words to an older original of mine called "Playing Jazz," which has become the title of the show. I came up with a story, writing twenty songs in all, and recorded it for the N.D.R., but I am not too happy with the results, as it needs more work.

I have just retired after twenty-eight years playing for the North German Radio Orchestra, but I like to keep busy, because I'm a workaholic. I teach a lot and I'm a professor at two universities, and I have also been involved in two musicals. The first one concerns all these stories I have been telling you. About five years ago, a friend told me that I should write my memoirs, and I said that if I ever did, it would be in the form of a musical. Soon afterwards I heard that Joe Albany had died, and he was a very important figure in my life. He was the first avant-garde jazz pianist, if you like, playing across bar lines ignoring strict tempo, and playing wild chords. He was very emotional and sometimes played poorly, but when he was "on," it was just fantastic. The Herald Tribune, however, gave him about three lines. Soon afterwards Chet Baker and Al Cohn died, and I was very touched. I wrote songs with lyrics for all three, and I thought, "What am I going to do with these songs?" That was when I decided to turn my memoirs into a musical, and I put words to an older original of mine called "Playing Jazz," which has become the title of the show. I came up with a story, writing twenty songs in all, and recorded it for the N.D.R., but I am not too happy with the results, as it needs more work.