© - Steven A. Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

Nancy

Paul Desmond and Doug Ramsey were pals.

All of us should be so lucky to have a friend like, Doug.

In honor of his late, buddy’s accomplishments, Doug has written Take Five: The Public and Private Lives of Paul Desmond, a work that has to rank as one of the best biographies of a Jazz artist ever written. Parkside published it in a lovely folio edition and should you wish to order a copy, you can do so by going here.

Doug has kindly given the editorial staff at JazzProfiles permission to offer his informative and insightful insert notes to the booklet that accompanies Paul Desmond - The Complete RCA Victor Recordings featuring Jim Hall.

© - Doug Ramsey, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

We were in an elevator in the Portland Hilton, waiting for the doors to close when the car jerked and dropped slightly, and a bell sounded.

"What was that?" a startled woman asked.

"E-flat," Paul Desmond and I said simultaneously.

I think that's when he decided we could become friends.

We had been acquaintances since a decade earlier when the Brubeck Quartet was playing a concert at the University of Washington

The liver thing had become a running gag. Desmond and good Scotch were, shall we say, not strangers. It amused him that after a physical examination in early 1976 turned up a spot on his lung, his liver was given a clean bill of health. He enjoyed the irony.

"Pristine," he said, "perfect." One of the great livers of our time. Awash in Dewars and full of health."

I think he was even amused by the circumstances of the discovery of his nemesis. He had gone to the doctor about foot trouble, and they found the cancer. The swelling of the feet turned out to be temporary and unimportant.

His mother was Irish and literate, his father German and musical, so it was probably inevitable that Paul Breitenfeld's verbal and musical selves would be witty, warm and ironic. Until near the end of his life, according to Gene Lees , Desmond thought his father was Jewish, but a relative said he wasn't. The name Desmond came from a phone book.

"Breitenfeld sounded too Irish," he told me.

Among those who knew him, his wordplay was as celebrated as his solos. He was quiet, quick and subtle, and some of his remarks have become widely published, like the one about his wanting to sound like a dry martini. One night at closing time at Bradley's, Jimmy Rowles was packing his fake books, and Bradley Cunningham remarked that if Peter Duchin could have access to all of those chords, his prayers would be answered.

"Unfortunately for Peter Duchin," Desmond said, "all of his prayers have already been answered.”

Hanging on our dining room wall was Barbara Jones' large oil painting of four cats stalking a mouse. Seeing it for the first time, Paul said, "Ah, the perfect album cover for when I record with the Modern Jazz Quartet."

"You'll notice that the mouse is mechanical," I pointed out.

"In that case," he said, "Cannonball will have to make the record."

Like all true lovers of language and humor, Desmond knew that the only good pun was a bad pun. He and Jim Hall conspired to conceive a sort of Jazz Goes to Ireland

Paul loved to visit our house in Bronxville, a half-hour north of Manhattan 55th Street 6th Avenue

After dinner, we sat on the verandah and talked, often for hours but never non-stop. There were long, comfortable silences.

In the years following the dissolution of the Brubeck Quartet, Desmond was semi-retired, playing only when he was presented the opportunity to work with musicians he admired or, in at least one case, to help someone. He was one of the first to play the Half Note when it moved from among the warehouses and garages of lower Manhattan

He appeared fairly often with the Two Generations of Brubeck troupe, hit the road with the old quartet in the 25th anniversary reunion tour in the winter of 1976, and traveled to Toronto now and then to work at Bourbon Street with Ed Bickert, Don Thompson, Jerry Fuller and, sometimes, Terry Clarke. In 1969, Paul was in the all-star band assembled by Willis Conover for Duke Ellington's 70th birthday part at the White House, the only domestic affairs high point of the Nixon administration. That night, as I have recounted elsewhere, Paul did an impression of Johnny Hodges that was so accurate that it caused Ellington to sit bolt upright in astonishment, an effect that gave Desmond great pleasure when I described it to him.

At the New Orleans Jazz Festival the same year, there was a memorable recreation of the Gerry Mulligan Quartet with Desmond as the other horn, Milt Hinton on bass and Alan Dawson the drummer. In New Orleans

Taking in one incredible jam session in the ballroom of the Royal Orleans Hotel, we witnessed Roland Kirk surpassing himself in one of the most inspired soprano sax solos either of us had ever heard. In a fast blues, Kirk used Alphonse Picou's traditional chorus from High Society for the basis of a fantastic series of variations that went on for chorus after chorus. We were spellbound by the intensity and humor of it, and Paul announced that henceforth he would be an unreserved Roland Kirk fan, even unto gongs and whistles. In the same session, Jaki Byard rose from the piano bench, picked up someone's alto saxophone and began playing beautifully.

"I wish he'd mind his own business," Desmond said.

About his own playing, he was modest, even deprecatory. "The world's slowest alto player," he called himself, "the John P. Marquand of the alto sax," and he claimed to

have won a special award for quietness. He was reluctant to listen to his recordings, although once after dinner when we'd had enough Dewars he agreed to hear a Brubeck concert I had on a tape never issued commercially. I intrigued him into listening by insisting that his solo on Pennies from Heaven was among his best work. In my opinion, Paul's solos tend* ed to be too short, but on this piece he stretched out for ten choruses of some of his most architectonic playing, full of inventive figures, sly rhythmic twists and ingenious quotes.

He nodded along with himself, laughed a couple of times (in the right places, obviously) and when it was over said, "I agree." That's the closest I ever heard

Desmond come to approval of his own playing.

During those final nine years, he was allegedly working on a book about his life and times in music. It was to called, How Many of You Are There in the Quartet, after a question asked by airline stewardesses around the world. There were periodic negotiations with agents and publishers, even an advance, but little of the book actually made it onto paper. The only chapter in print was in Punch, the British humor magazine. In an account of the Brubeck group's engagement at a county fair in New Jersey, Desmond melded a horse show, volunteer firemen's' demonstrations, Brubeck's only known appearance on electric organ, and a marathon Joe Morello drum solo into a montage worthy of S.J. Perelman. The book, he now and then claimed, was mainly an excuse that allowed him to hang out with the writers at Elaine's. That two-page cadenza, his liner notes, and a few letters remind us of Paul's literary ability. He was a creative writing major at San Francisco State College in the '40s, but he got sidetracked.

We talked by phone fairly often in the last years of his life, when I was living in San Antonio

His housekeeper found him dead on Monday.

© - Paul Desmond/Radio Corporation of America, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

Paul Desmond's original liner notes for TAKE TEN (RCA LSP 2569):

TAKETEN: further reflections on "Black Orpheus" and other timely topics...

This space is usually occupied, as most hardened collectors know, by the prose stylings of George Avakian. I'm taking his place this time partly because he's up to his jaded ears in Newport

Briefly, then, I'm this saxophone player from the Dave Brubeck Quartet, with which I've been associated since shortly after the Crimean War. You can tell which one is me because when I'm not playing, which is surprisingly often, I'm leaning against the piano. I also have less of a smile than the other fellows. (This is because of the embouchure, or the shape of your mouth, while playing, and is very deceptive. You didn't really think Benny Goodman was all that happy, did you? Nobody's that happy.) I have won several prizes as the world's slowest alto player, as well as a special award in 1961 for quietness.

My compatriot in this venture is Jim Hall, about whom it's difficult to say anything complimentary enough. He's a beautiful musician-the favorite guitar-picker of many people who agree on little else in music, and he goes to his left very well. Some years ago he was the leading character, by proxy, in a movie starring Tony Curtis (SWEET SMELL OF SUCCESS), a mark of distinction achieved only recently by such other notables as Hugh Hefner and Genghis Khan. He's a sort of combination Pablo Casals and W.C. Fields and hilariously easy to work with except he complains once in a while when I lean on the guitar.

Gene Cherico, who's becoming a thoroughly fantastic bass player, has only been playing bass for the last eight years. (Before that he was a drummer, but a tree fell on him. No kidding, that's the kind of life he leads.) On TAKE TEN he was replaced by my sturdy buoy and hard-driving friend Eugene Wright.

Connie Kay is, of course, the superb drummer from the Modern Jazz Quartet, and if a tree ever falls on him I may just shoot myself. He's like unique.

About the tunes: TAKE TEN is another excursion into 5/4 or 10/8, whichever you prefer. Since writing TAKE FIVE a few years back, a number of other possibilities in the 5 & 10 bag have come to mind from time to time. TAKE TEN is one of them. THEME FROM 'BLACK ORPHEUS' and SAMBA DE ORFEU, along with EMBARCADERO and EL PRINCE; are in a rhythm which by now I suppose should be called bossa antigua. (It's too bad the bossa nova became such a hula-hoop promotion. The original feeling was really a wild, subtle, delicate thing but it got lost there for a while in the avalanche. It's much too musical to be just a fad; it should be a permanent part of the scene. One more color for the long winter night, and all.)

ALONE TOGETHER, NANCY and THE ONE I LOVE are old standards I've always liked. They were arranged, more or less, while we were milling about drinking coffee and all. This approach, while making for a comfortable looseness, usually leads to general apprehension towards the end of the take and frequent disasters, but occasionally you get a fringe benefit. At the end of ALONE TOGETHER, Connie hit the big cymbal a good whang there and it sailed off the drum set and crashed on the floor. After the hysterical laughter subsided we were getting set to tear through it one more time but we listened to it anyway, out of curiosity, and it sounded kind of nice so we left it in. That's one of the few advantages this group has over the MJQ-if Connie's cymbal hits the floor on an MJQ record date, you by God know it, but with this group you can't really be sure.

George Avakian was benevolently present at all stages of getting this record together, and Bob Prince, doubtless overwhelmed at having a song named after him, appeared frequently with advice and counsel which was totally disregarded.

I would also like to thank my father who discouraged me from playing the violin at an early age.

PAUL DESMOND

© - Paul Desmond/Radio Corporation of America, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

Paul Desmond's original liner notes for BOSSA ANTIGUA (LSP 3320):

DELINEATIONS BY DESMOND

It's me, Paul Desmond, rapidly aging sax player with the Brubeck Quartet, sometimes called the John P. Marquand of the alto, and again playing hookey from the mother lode with the same group of sturdy compatriots that made TAKE TEN such a Joy to record. On bass is the Jovial presence of Eugene Wright, without whom the entire Brubeck operation would grind to a halt in a matter of hours. On drums, the master time-keeper of the Modem Jazz Quartet, Connie Kay -who, if he didn't exist, would be much too perfect ever to be imagined by anyone. And on guitar, the redoubtable (that means the first time you hear it you don't believe it, and when you hear it again later you still don't believe it) Jim Hall.

The term bossa antigua (it means, or at least it should, "old thing," as opposed to "new thing") began as a slightly rueful play on words, because by the time I got around to doing a few bossa nova tunes on TAKE TEN it was several years after the first flash from Brazil and couldn't property be called a new thing any more. This album carries the term a step further, in that the rhythm on several tracks is a sort of skeletal bossa nova with various old-timey flavors added. ALIANCA, for instance, has Jim Hall functioning as the only accredited Brazilian delegate, accompanied by routinely impeccable Connie Kay shtick and a nice comfortable New York HAS A THOUSAND EYES contain other variations, ranging from Early Calumet City Strip to a subliminal fraelich. (If any of you feel creative out there, you could get together some rainy night and figure out an Old Thing dance to go along.)

The tunes, except for SHIP and NIGHT, are mostly originals. O GATO was written by Jim Hall's friend Jane Herbert, and it's as charming as she is, which is saying a lot. The others are tunes I wrote. One is based on a minor adaptation of a melody indigenous to early American coffee houses, a few are extensions of themes that have been wandering through my head recently, and the one called CURASAO DOLOROSO is a sort of three-stage operation.

Originally I'd wanted to do HEARTACHES, because it seemed so incongruous and because the original record of it had something of the same Neolithic connection to bossa nova as early marching bands had to Gerry Mulligan. I wrote a different set of changes for it and we tried it, and it was so horrible that George Avakian emerged from the control room in the middle of the first take, waving his arms and shuddering. (This is a musical milestone of sorts, since George usually smiles serenely thru the most disastrous takes imaginable, hoping that something good will somehow happen and he'll be able to splice it in later. I think the only other time he walked out in the middle of a take, the studio was on fire.)

So, on a later date we used the chords and avoided the melody, which is what you're supposed to do in jazz anyhow, come to think of it, and it worked out nicely. (Since it's a different melody and a different set of chords, the writers of HEARTACHES won't be around looking for royalties - but if they ever feel like dropping by for a drink, I'm usually home between 4 and 6.)

As always, George Avakian masterminded the entire operation effortlessly, even with a telephone more or less permanently installed in one ear. (There was one point, I must admit, when the only way I could get his attention was to go out to the phone booth and call him.) I don't know how the phone calls worked out, but I love the album.

PAUL DESMOND

© - Doug Ramsey, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

PAUL DESMOND WITH JIM HALL

Until his series of RCA Victor dates in the 1960s, Paul Desmond did little recording as a leader, most unusual for a star soloist. In 1954 he had two Fantasy sessions, one with trumpeter Dick Collins and tenor saxophonist Dave Van Kriedt, colleagues from the Brubeck Octet; the other with guitarist Barney Kessel and the Bill Bates singers. The entire output of those encounters fit on a 10-inch LP made of green vinyl (everything done by Max and Sol Weiss, Fantasy's founders, was colorful). In the notes for it, Paul wrote, "My name is Paul Desmond and here I am 30 years old and this my first album in which I am not breathing down somebody else's neck...." In 1956, Desmond put together a quartet for another Fantasy album (red vinyl) with Don Elliott on mellophone and trumpet and elephants rampant on the cover. Desmond and Gerry Mulligan shared leadership of a 1957 session for Verve. He and guitarist Jim Hall linked up for a quartet date for Warner Bros, in 1959.

CD1

DESMOND BLUE

For four years beginning in mid-1961, Desmond was in Webster Hall or RCA's famous Studio A 19 times for sessions that produced five albums with Hall. The first to be released was Desmond Blue (later re-released on CD as Late Lament, with the addition of the previously unissued Advise and Consent, Autumn Leaves and Imagination). The arrangements for strings and horns were by Bob Prince, who had established his reputation as the composer of a staple of the modern ballet repertoire, New York Export: Op. Jazz. "I'd always wanted to hear Desmond with strings," Prince told Will Thornbury. "It was a dream come true."

Prince's recollection of Paul's modus operandi at the strings dates reminds us of Desmond's dedication to spontaneity.

"He was a wonderful musician," Prince told Thornbury, "one of the few to transform the saxophone and shape it into a new sound. I've never known anyone with such a pure tone - one that I'd never heard before and won't again. When it came to playing with strings and woodwinds, he wanted the experience of going into the studio and having a new toy to play with. It really came down to that, because in many cases I was going to show him what I'd done and he'd say, 'No, no, that's all right—just go ahead and do it.' He didn't really want me to come over and show it to him on the piano or even look at it on the score, because he liked that, just like he liked going in with Jim and the rhythm section and being surprised by them. I was amazed by what he did. In all of the album there's one chord—one point—where I stuck in an augmented eleventh, and had I known he was not going to augment the eleventh, I'd have thought twice about putting in the upper functions. That's the only exception, and it only happened for about a quarter of a bar. I'm not telling where that is."

The empathy between Paul and Jim Hall is introduced in My Funny Valentine following the neo-baroque introduction written by Prince. It is more fully disclosed in I've Got You Under My Skin when the strings lay out. Desmond plays a chorus with only Milt Hinton's bass and Robert Thomas's drums behind him, then Hall begins a pattern of gently prodding chords and moves the intensity up so that by the time the strings re-enter on a key change, the swing has reached its highest level of the piece.

CD2

TAKE TEN

Take Ten was Desmond's follow-up composition to Take Five, for the Brubeck Quartet a hit record and for Paul a dependable annuity that is still producing considerable income for his estate. The bassist for the title tune of Desmond's second RCA album is Eugene Wright, fellow Brubeckian and shaman of 5/4 time who, in the early sixties when 5/4 was Sanskrit to most jazz musicians, would hold little counting seminars backstage: "1,2,3/1,2," he would instruct the locals, "that's the only way you can keep track of it until it becomes natural.” In Take Ten, it is obviously natural to Gene. Desmond is misterioso, Near-Eastern and bluesy.

Hall was one of the first American musicians to return from Brazil

At least one hearing of Alone Together can profitably be spent concentrating on Connie's snare accents and cymbal work, little kicks of encouragement. Paul, at a fairly good clip, marries relaxation and irresistible swing, especially in his second solo. Jim quotes Dizzy Gillespie's Anthropology and in the bridge of his second solo chorus has the kind of chord fiesta that makes grown men weep, if they are guitarists.

The structure of this song is a normal AABA, but the first two A sections are 14 bars instead of the usual eight. The composition hangs together so well, the eccentricity is not obvious.

The originally issued take of Embarcadero has nifty counterpoint in the first 16 bars following the guitar solo. One of several original Desmond bossa novas, the tune could be named after the Embarcadero in his native San Francisco Rio , or both. Antonio Carlos Jobim's gorgeous theme from the film Black Orpheus brings us to Kay laying down the basic bossa nova pattern, Hall and Cherico in rhythmic cahoots and Paul soaring. The tag is played as written, then the piece is taken out on a vamp ending.

The One I Love gets a fluid performance with no quotes and no clichés. In his solo, Hall alternates legato and punchy passages to great effect. Out of Nowhere has interesting Desmond modulations in the opening chorus. Hall's comping is exemplary, and Kay negotiates a classic bop ride cymbal pattern throughout. Following Jim's two-chorus solo, he and Desmond trade twos, then Paul and the rhythm section do a chorus of stop-time.

CD3

GLAD TO BE UNHAPPY

Desmond's singing quality predominates Glad to be Unhappy, one of the best Rodgers and Hart ballads and one of their most unusual, with its ABA

Strolling is what Roy Eldridge was the first to call the practice of a horn soloist playing with only bass and drums. Desmond strolls nicely in the second chorus of Poor Butterfly. Hall's solo has fascinating chords and great intensity. Counterpoint raises its lovely head, and we have the closest thing to a Dixieland ending that you're likely to hear from this band.

Mel Torme's Stranger in Town offers a good example of why Desmond kept describing Eugene Wright with such adjectives as sturdy, dependable and buoyant. It is also, for alto saxophonists, a case study in tonal quality. In A Taste of Honey, Paul offers a small portion of the melody as written, then the piece becomes abstraction, employing that high, pure alto sound so many think of as Desmond. He loved waltz time and he loved minor keys, and this is the best of both worlds.

For Any Other Time, a Desmond original, Kay's drumming is smooth, the kind of rolling timekeeping a soloist loves to have behind him. Paul's hurdy gurdy lines reflect the joy expressed by Hi-Lili, Hi-Lo in the motion picture Lili. There is no way of knowing, but, given his admiration of elegant women (fortunately, for him, it also worked the other way), it may be that he was picturing Leslie Caron. It is well known that his Audrey from the mid-'50s was Hepburn. Speaking of women, which Desmond did with respect and some frequency, he made it a point to—ahem—know the beautiful models RCA hired to decorate most of his album covers. He once told me that using his picture on the Take Ten album not only probably frightened away record customers but left a gap in his social life.

Desmond is piping and plaintive in Angel Eyes; what an ear for subtle harmonic possibilities. Jim goes into one of his billowing chords routines, then Paul floats back in, melodic and, yes, lyrical. By the River Sainte Marie, written in 1931, may seem an unlikely jazz vehicle, but it works for Desmond, Hall and company in this amiable performance.

Jim Hall's All Across the City was first recorded in a classic session for Mainstream Records which featured him and fellow guitarist Jimmy Raney with tenor saxophonist Zoot Sims. The initial melody is reminiscent of Gershwin's Prelude in F. It might have been made to order for Desmond. Jim spreads composerly chords for Paul when the alto re-enters following the guitar solo, a splendid moment. Connie creates another with his cymbals suspension before the final statement.

All Through the Night must have been on Paul's mind because it was included in Brubeck's Cole Porter album, Anything Goes (for Columbia

CD4

BOSSA ANTIGUA

The Bossa Antigua album is another celebration of Desmond's favorite import, not taking Dewars into account. The title tune and Samba Cepeda (Orlando, the great first bassman?) are the same melody. Cepeda is issued here for the first time on CD. Of the two takes of The Night Has a Thousand Eyes, the one originally issued is given a less overt bossa nova treatment than the alternate (track 9). The original issued take of O Gato, recorded on August 20,1964 , is relaxed over Kay's sizzling bossa nova rhythm. The alternate take was the sole successful effort in a session on July 30,1964 . Samba Cantina could be the "minor adaptation of a melody indigenous to early American coffee houses" slyly referred to by Desmond in his notes for the Bossa Antigua LP. Curacao Dolorosa may commemorate a painful experience on an island in the Netherlands Antilles or a hangover from a liqueur. Its genealogy, as Paul explained it in his notes, involves, more or less, the song Heartaches.

The fetching melody of A Ship Without a Sail is lovingly played by Desmond. Hall, making the difficult sound easy, turns in one of his best solos. Kay successfully uses the unconventional device of accenting the second beat of each bar. Alianca is another of Paul's attractive originals. His The Girl from East 9th Street is highlighted by lovely descending thirds that begin in the ninth bar.

CD5

EASY LIVING

The Easy Living album begins with When Joanna Loves Me, a little-known love song that is seldom recorded. The tempo is medium, with Wright playing in two for the first chorus, then blossoming into a gently walking 4/4 for Desmond Hall's beautifully played, slight sad and regretful improvisations. Kay's drumming here is typical of his unique combination of lightness and firmness.

Desmond lilts along through the melody of That Old Feeling, then shifts up for a cruise through three increasingly momentous choruses. Hall's invitation to dance is concealed in an oblique reference to Benny Goodman. Polka Dots and Moonbeams is given a faster tempo than is usually applied to this famous ballad, providing sprightly impetus to the solos but draining none of the interest from Jimmy Van Heusen's intriguing chord changes.

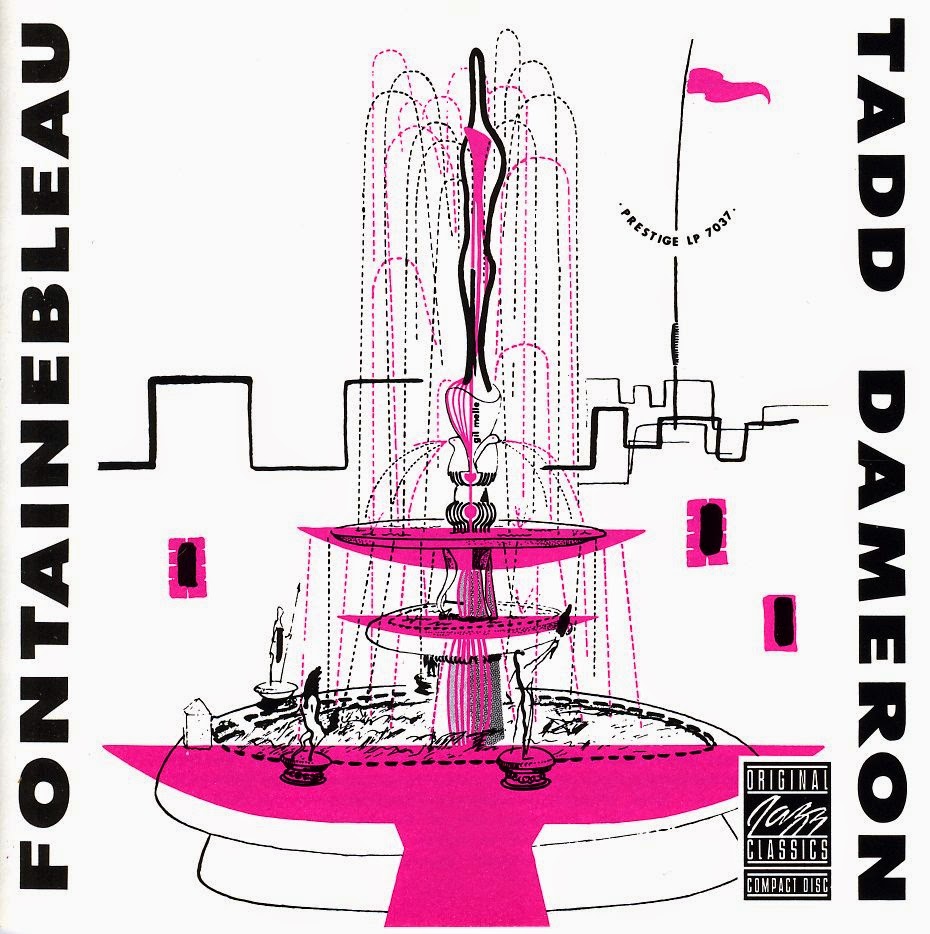

Another of Van Heusen's treasured harmonic patterns is contained in Here's That Rainy Day, in which Desmond makes allusions to Man With a Horn, Tadd Dameron's Hot House, I've Got a Right to Sing the Blues and Time After Time. Hall leaves the hiding of clues for tune detectives to his partner and settles into his work with a section of low-register reflections that blooms into one of the guitarist's celebrated gardens of chords.

There were problems with takes of two pieces recorded by Desmond, Hall, Wright and Kay on September 9, 1964 . They were rejected and had to be redone later in the month. But on Easy Living, everything worked. Desmond follows Hall's quiet introduction with a piping reading of the seductive Ralph Rainger melody, then provides a classic example of his legato ballad style—seamless lyricism and the creation of pure melody.

Percy Heath's authority and mastery of the beat married to the assurance and easy ride of Kay's cymbals buoy Paul's delighted exposition of Lerner and Loewe's centerpiece from My Fair Lady, I've Grown Accustomed to Her Face. At the risk of pointing out the obvious, please don't miss Desmond's modulations in the second chorus or Jim's logic in the development of ideas in his wonderfully linear solo. The same team, virtually the same tempo, and the same relaxation, passion and inventiveness in the art of improvisation are hallmarks (so to speak) of Bewitched. The song is one of the finest works of Rodgers and Hart, who could be considered the Lerner and Loewe of their time. Or is it the other way

In Blues for Fun, the fun begins with a chorus of walking bass by Gene Cherico, an unsung hero of the instrument. Among other things, on this piece Desmond proves that the world's slowest alto player had no problem with fast tempos, that he and the blues understood each other and, in his unaccompanied chorus, that he knew Lester Young inside out. Hall's solo and his riff behind Desmond's out-chorus are the work of a master architect of the blues.

Keeping company with All Through the Night in tape purgatory was Gene Wright's Rude Old Man, an invaluable addition to the accumulated evidence of the blues prowess of Desmond and Hall. The first chorus lays down Gene's urgent little riff. The second features Paul and Jim in contrapuntal call-and-response. The balance of the piece is devoted to expressing the profundities that the best players can elicit in a thoroughgoing exploration of the limitless possibilities of the good old basic, unadorned blues in B-flat. Toward the end of his solo, Jim gets, as they have been known to say in parts of Mississippi

Paul, who always had a sense of occasion, died on Memorial Day, 1977. He was 52 years old. Perhaps not coincidentally, the Brubeck clan gathers each Memorial Day at the big Connecticut Dave and Iola are surrounded by their many musician sons, their daughter, other family members and friends. Always, much of the conversation will be about Paul, and there will be considerable laughter and head-shaking as puns, witticisms and plays on words are passed around. Eyes will moisten. Someone will say that Desmond manages to be a part of every day's thoughts. That someone is likely to be Dave .

"I think about Paul all the time," Brubeck told me. "We were together for so many years that I find myself remembering how Paul would have reacted to music and seeing our friends through his eyes. And around here we're always saying, "Paul would have loved that," or "I wonder what Paul would have said about that." Mort Saul and I got together the other night after a concert. We swapped Desmond stories for an hour and could have gone on all night. Paul's always with us. He's a presence."

Once, when we were talking about something else, Brubeck stopped, looked into the distance for a moment and said, "Boy, I sure miss Paul Desmond."

I couldn't say it better.

Boy, I sure miss Paul Desmond.

-DOUG RAMSEY