Anyone who has ever had anything to due with the instrument in a Jazz environment, simply understand this - Joe was incomparable.

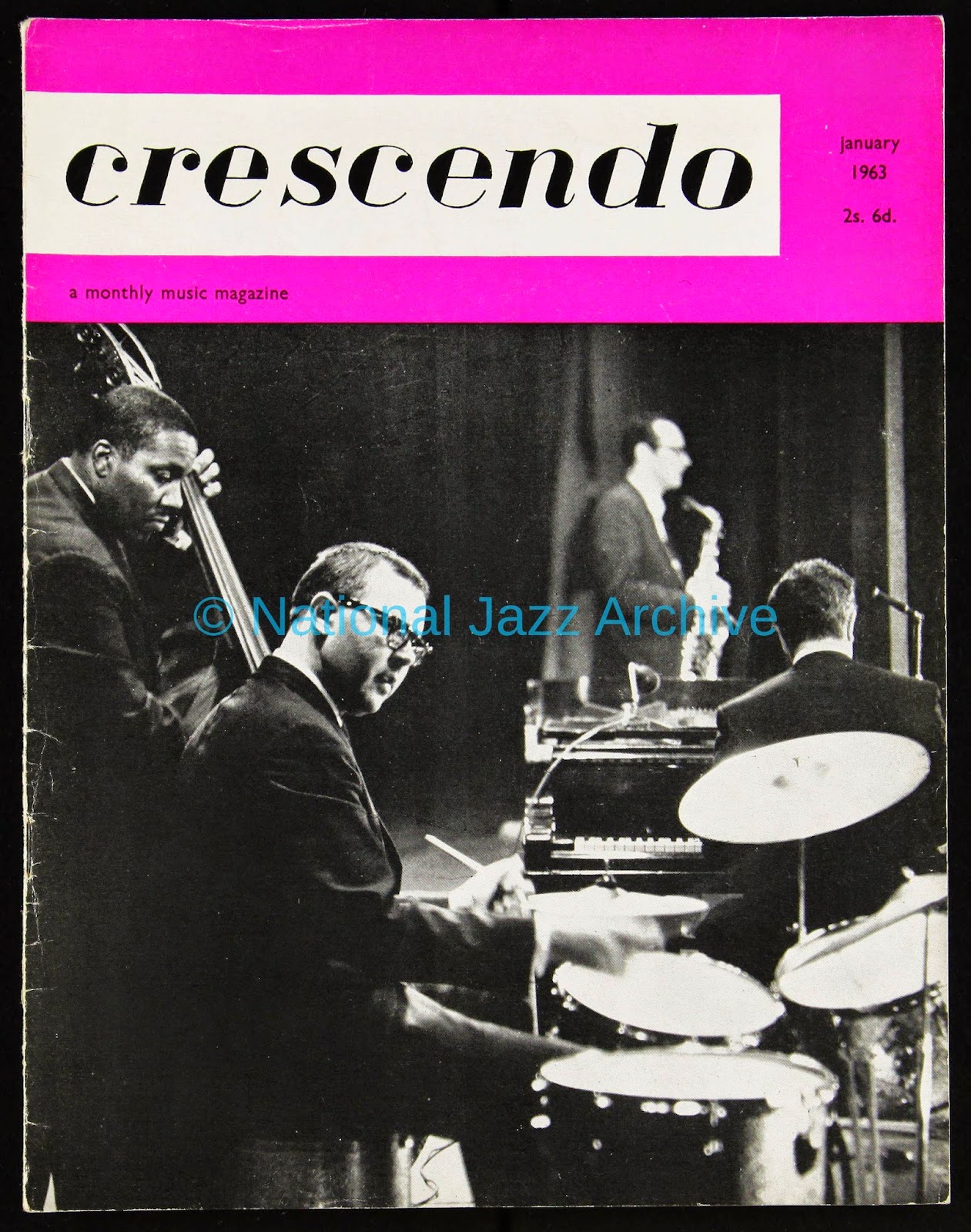

While we are fortunate to have many recorded examples of his playing in small groups, especially those he made during a three years association with pianist Marian McPartland’s Trio [1953-1956] and those made as a member of the “classic” Dave Brubeck Quartet [1956-1968], sadly, there are too few recordings of his extraordinary drumming in a big band setting.

The following insert notes by Rick Mattingly to Joe Morello [RCA Bluebird- 9784- 2 RB] provides some explanations for this void.

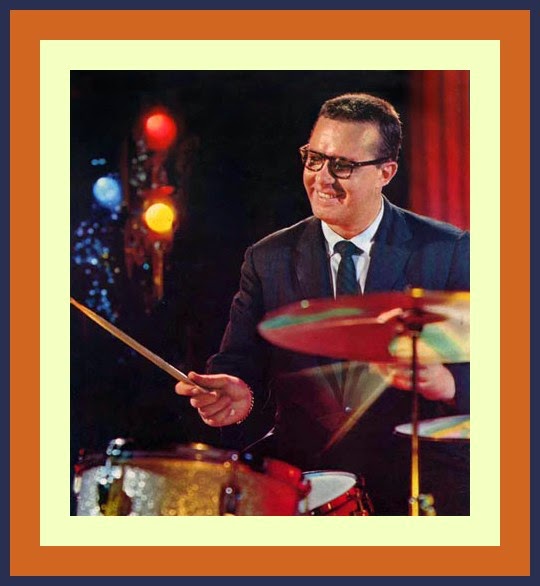

“It was the early '60s, and the hottest jazz group going was the Dave Brubeck Quartet, who had achieved the rare distinction of having a number-one hit on the pop charts. The tune was called "Take Five," and its two main points of interest were the 5/4 time signature and the drum solo, played by Joe Morello. The record epitomized the "cool jazz" of the period, and Morello was the ideal drummer for that era. His style was firmly rooted in the swing and bebop traditions, but Joe was also a schooled performer who had studied with George Lawrence Stone of Boston and Billy Gladstone, snare drummer at Radio City Music Hall. Morello's polished technique, combined with the odd-meter time signatures favored by the Brubeck group, gave his playing an intellectual quality that fit right in on the college campuses where the Brubeck Quartet enjoyed much of their success. With his glasses and generally studious expression, Joe even looked somewhat like a college professor.

Among drummers, Morello was highly respected. When he first arrived in New York in the mid-'50s, his first order of business was to check out all of the local drummers. Stories are still told about how he would approach a drummer and ask about some little technical trick he had seen that drummer pull off. The other drummer, often with a patronizing air, would demonstrate his lick for Joe, who would then say, "I think I see what you're doing. Is this it?'— thereupon playing the drummer's lick back at him faster and cleaner.

When Morello began a three-year stint with Marian McPartland at New York's famed Hickory House in 1952, it gave all the other drummers in town the chance to check out Joe. Many still recall sitting with him at a back table between sets, where he would demonstrate his techniques by playing on a cocktail napkin. But while Morello quickly proved that he had all the chops of a Buddy Rich, he became noted for his restraint, only pulling off his pyrotechnics when it was musically appropriate to do so.

Morello joined Dave Brubeck in 1955, for what was to become a 12-year association. About the same time, he had offers from both Benny Goodman and

Tommy Dorsey, but he turned them down to go with Brubeck. "At the time," Joe says, "it looked to me as if big bands were on the way out. So it seemed to make more sense to go with Dave." It was a wise decision, as history has borne out. The Brubeck Quartet was the perfect setting for Morello to develop and display his unique approach, and during those years he repeatedly won the "best drummer" award in down beat,Metronome, and Playboy jazz polls.

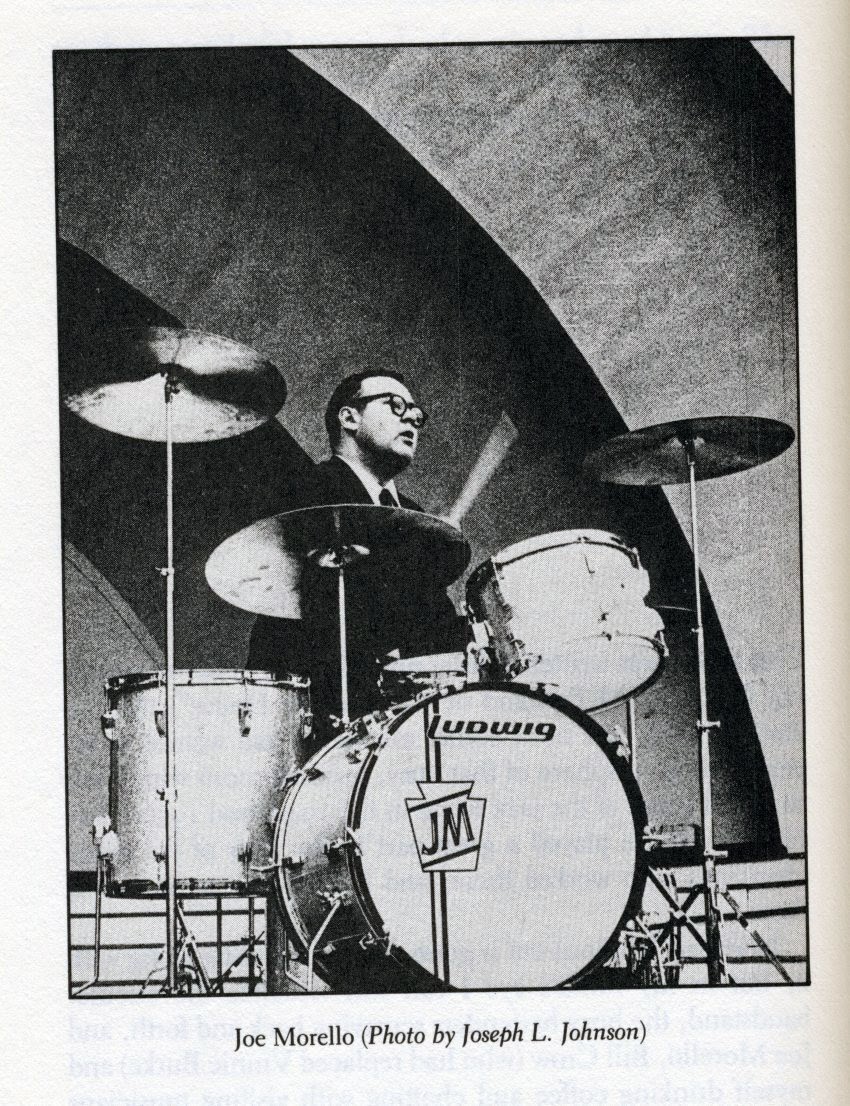

During his tenure with Brubeck, Morello also became involved with the Dick Schory Percussion Pops Orchestra, with whom he recorded a couple of albums on RCA. After one of those sessions, Schory remarked to Morello, "It's about time you made your own record." The RCA executives agreed, and sessions were set up in June 1961.

"We took the title of the album, It's About Time [LPM-2486] from Schory's comment," Morello recalls. "Then we decided that we would only do songs that had the word 'time' in the title." Interestingly enough, despite the title of the album and the reputation Joe had for his expertise with unusual time signatures, there was very little of that type of playing on the record. "I wanted to do straight-ahead things on my album," Joe explains, "because I was doing so much of that other stuff with the Quartet. I wanted this album to be a whole different concept."

Because Morello was on the road so much with Brubeck, composer/arranger Manny Albam was enlisted to prepare the music and book the musicians. One player that Morello specifically requested, though, was saxophonist Phil Woods. "Phil and I grew up together in Springfield, Massachusetts," Joe says. "We played together as kids. He would be listening to Charlie Parker, I would be listening to Max Roach, and we would get together and try to imitate them. Phil and I always dreamed of having a group together, and although that never happened, we did make a few records together over the years. He's such a great player."

Another notable player on that album was Gary Burton, who was still a teenager at the time. "I met Gary through Hank Garland," Joe recalls. "I had worked with Hank at the Grand Ole Opry when I was 17. Then, after I was with Brubeck, I did a record with Hank, and he had this kid playing vibes. It was Gary, and that was his first album [Hank Garland, Jazz Winds from a New Direction, [Columbia LP 533]. When Gary came to New York, he stayed with me for a while, and then he stayed with Manny Albam after that. We did my album about a year after we had done Hank's record, and Gary had really improved a lot." Morello had also gotten Burton involved in Schory's Percussion Pops Orchestra, where they recorded together, and when Burton did his first solo a I bum for RCA [LPM 2420], New Vibe Man In Town, Morello was the drummer.

It's About Time did well enough that RCA invited Morello back to do a second album a year later. A few of the tunes on the first album had featured a brass section along with Phil Woods on sax, so this time it was decided to do a full-out big band record. Again, Manny Albam was enlisted to write the charts and hire the musicians, and again Phil Woods and Gary Burton were involved. But the album was never released. "RCA wanted me and Gary to have a group together," Joe remembers. "We had played on each other's albums, and RCA said that if we started a group together, they would really get behind it and publicize us. But I was too comfortable with Dave, so I wouldn't do it. And RCA couldn't see putting all this promotion behind my solo albums if I was still going to be doing all of that recording with Dave on Columbia. So they just didn't release the second album."

Those tapes remained in the RCA vaults for 27 years. But Morello had a copy, and he would occasionally play it for people. One person he played it for was Danny Gottlieb, a student of Joe's who has had a distinguished career of his own, working with such notables as Gary Burton, the Pat Metheny Group, John Mclaughlin, and the Gil Evans Orchestra, and who now has his own group, Elements. Gottlieb subsequently brought a copy of the tape to producer John Snyder,along with It’s About Time, and the results are contained herein [Joe Morello RCA Bluebird- 9784- 2 RB]

This collection kicks off with "Shortnin" Bread," from the unreleased big band album. "This was a little drum feature that we used to do with the Quartet," Joe recalls. "It always went over well, so I wanted to do it on my album." Morello's melodic approach to the drums is well represented here, as is his ability to kick a big band. "I think I could have been a good big band drummer if I'd had the chance to play with one for any length of time," Joe says. Judging by this, he certainly could have.

![]()

Next up is "When Johnny Comes Marching Home," featuring Morello's brush playing. Playing precise military-style figures with brushes is no mean accomplishment, and it is a good example of how Morello utilized his considerable technique in a subtle way. On the surface, Morello's drum breaks and rhythmic figures are rather basic ("l just played simple little things tha tfit with the band," he says), but when one considers the technical difficulties involved in achieving crisp articulation with brushes, one begins to appreciate Morello's degree of control.

Morello's control of fast tempos is evident on "Brother Jack," also from the unreleased big band sessions. "That's a pretty good tempo for a big band," Joe says. "Manny didn't want it to be that fast, but I wanted to take it up." Joe shows off his blazing single-stroke roll technique during the drum breaks in the middle, and ends the tune with a more thematic solo. Phil Woods is also featured on this tune.

"Every Time We Say Goodbye" is from It's About Time, and utilizes a brass section to enhance the core quintet. Morello concentrates on supporting the soloists, Woods, Burton, and Bob Brookmeyer.

Also from the first album, "Just in Time" is a quintet tune with spirited solos by Woods, Burton, and bassist Gene Cherico. "I had pretty good hands back then," Joe says of his four-bar breaks, which display his sense of phrasing, as well as his sense of humor.

"It's Easy" comes from the big band sessions, and Joe remembers it as the last thing that was recorded. "I didn't have a drum chart for this, and we only had time to do a couple of takes," Morello recalls. "When the first drum break came up, I didn't know what was going on," he laughs. Nevertheless, by the second break, Morello sounds as if he had been playing the tune for years. Colorful hi-hat work adds to the mood of this piece.

"Shimwa," is a piece that Morello wrote for the Brubeck Quartet. "We didn't play it that much, though," Joe says, "so I had Manny arrange it for the big band album. It's basically a showcase for the drums. I wanted an African-type motif, and I tried to get the effect of a couple of drummers playing." The effect is achieved by Morello's use of polyrhythms, and by his ability to set up an ostinato pattern with his left hand, leaving his right hand and bass drum free to play contrasting rhythms.

Another "time" tune, "Summertime" was arranged by Phil Woods, and features solos by Woods, Burton, and pianist John Bunch, who was no stranger to working with good drummers; he had recently been with Buddy Rich's band. Morello concentrates on straight-ahead, supportive playing here. "I didn't want to do too many drum solo things," Joe explains. "On a lot of albums by drummers, every tune has a drum solo, and let's face it, too many drum solos are boring. I wanted to be more musical."

"A Little Bit of Blues" is another big band chart by Manny Albam, and features distinctive solos by Hank Jones and Clark Terry. No technical fireworks from Morello here, just great feel.

"It's About Time" was the title tune from th first album, and is basically a setup for Morello's drum solo. All of the Morello trademarks are here: the speed, the polyrhythms, the left-hand ostinatos, the phrasing. Another feature of the tune is its changing time signature; it goes into 6/4 for Phil Woods' solo.

The quintet from the first album is featured on "Every Time "which displays the smoother side of Morello's brush playing. Joe has high praise for Burton's contribution to this piece. "Gary had really learned to phrase well," Joe comments. "When I first heard him, he was playing everything right on the beat, but by the time we recorded this, he was really adept at back-phrasing." Bunch and Cherico also have solo spots here, and Morello adds a melodic drum break.

Phil Woods wrote "MotherTime"for the first album,an uptempo 12-bartune

that features solos from Bunch, Cherico, Burton, and Woods, followed by fours between Morello and Woods. Joe's breaks include his use of space and his famous left-hand ostinato.

"Time After Time" is a ballad that features Phil Woods, backed by Morello's sensitive brush playing. Unlike a lot of drummers, Morello always disengaged his snares when playing brushes, which produced a drier, more defined sound, "Phil has such a nice feel in this tune," Morello comments, "especially during the double-time section."

Considering the tempo of "My Time Is Your Time," not to mention the large ensemble, most drummers probably would have used sticks. But Morello pulls out his brushes, driving the band with intensity rather than volume. Burton and Woods solo, and Morello takes several breaks in which he shows again that he can be as articulate with brushes as most drummers are with sticks.

This collection concludes with a Dave Brubeck composition, "Sounds of the Loop," from the unreleased big band album. During the ensemble section of the tune, Morello displays a more "open" style of big band drumming, only catching the major figures and concentrating more on keeping the time moving forward. The chart is primarily a vehicle for Morello's drum solo, and it is a definitive example of melodic, thematic drumming.

The music on this album represents Joe Morello at his peak, and shows off some sides of his playing that have been relatively undocumented. Here was a drummer who was equally at home with small combos and big bands; a drummer who could handle the most complex time signatures and who was equally adept at straight-ahead swing; a drummer who had as much technique as any drummer who has ever lived, but who always put the music first.

—RICK MATTINGLY

Joe Morello - "It's About Time"

© - Steven A. Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“One thing about Dave Tough: he always was Dave Tough, just as Buddy Rich always was what he was. Tough realized we are what we are. The important thing is to be put into a musical situation where what you are can ‘happen.’ Tough found his place with Woody Herman.” [And Joe Morello found a place where he could ‘happen’ in the classic Dave Brubeck Quartet from 1956-1968].

- Mel Lewis, drummer and bandleader

“Joe Morello: One of my favorite drummers was Davey Tough. 'Cause he could keep a nice rhythm with a band and he kept good time. He didn't hardly do anything with his left hand. He was just straight ahead on the big cymbal, but he got it cookin' real good.

Sidney Catlett I used to listen to.

Scott K Fish: Did you ever get to meet those guys?

JM: Sid Catlett I met once. One time in New York.

J.C. Heard was another fine drummer. I don't know if you've ever heard of him.

And then Jo Jones, who is still a good friend of mine. He's still here. Old man Jo Jones. ‘Jonathan Jones to you.’ [Morello mimics Jo Jones’ raspy voice.] Boy, that guy taught me a lot, because I played opposite him for about six or seven weeks at the Embers. He was working with Tyree Glenn and Hank Jones. He use to play his bass drum open, see. He had a little 2O-inch bass drum, and a snare drum, cymbal, and a hi-hat cymbal. That's all he had. Oh, and he had one little floor torn. And he'd get up on the drums with brushes and he'd get that bass drum going. [JM taps drum stick on leather sofa cushion, imitating the sound Jo Jones' would get from this bass drum at the Embers].

SKF: When you say "open," you mean he had no felt strips at all?

JM: Not at all. [Keeps tapping stick on couch] and he'd get a sound just like that. A good sound.

I'd get up there and I'd play something and it would go BOOM BOOM BOOM BOOM. And I'd say to him, "Jo, how do you do...?" And he wouldn't talk to me for the first two or three days. He just sort of flugged me off, you see.

But I sat down and I watched that f***in' bass drum, and I said, "I'm doing something wrong."'Cause he sounds tap, tap, tap, and when I hit it it goes BOOM, BOOM, BOOM. I couldn’t play it!

The only way you could play it, I found out, was by pressing the beater ball on the bass drum pedal into the head. He’d play up on his foot like that, but he’s been playing it like that for so long that he can control it, see. Jo was always playing toes down with his heals up!

I learned a lot about hi-hats from Jo, because Jo would always get a breathing sound from his hi-hats. We became good friends.”

- Scott K. Fish, Modern Drummer, 1979

In a previous posting entitled “Joe Morello In A Big Band Setting,” we highlighted Rick Mattingly’s insert notes to Joe Morello RCA Bluebird- 9784- 2 RB, a CD that essentially combined 7 previously unreleased big band sessions from 1961-62 with eight of the ten tracks that were issued featuring Joe Morello in a quintet setting on the RCA LP It’s About Time [RCA LPM-2486].

Since the original liner notes to It’s About Time were not included with the the CD reissue, the editorial staff thought it might be helpful and instructive to have these available online.

Joe’s quintet included his boyhood chum, Phil Woods, who also arranged some of the tunes along with Manny Albam [the arranger for all of the subsequently released big band charts], Gary Burton on vibes [these were some of Gary’s earliest recordings], John Bunch on piano and Gene Cherico on bass.

You will find two of the tracks from It’s About Time on the video tributes that conclude this portion of our ongoing feature on one of the most respected and revered Jazz drummers of all time.

ABOUT THIS ALBUM BY GEORGE AVAKIAN [Producer]

“Every limit in jazz and popular music has been stretched and broken with the passing years. Technical skills have been sharpened; musicians have turned what was once dazzling virtuosity into the professional norm. The frontiers of harmony are extended constantly—yesterday's radical dissonances are today's conventions.

"Times" have changed, too. The simple time-rhythms of the past are no longer enough for today's musicians. Improvised subdividing of the standard four-beat measure by the earlier jazzmen was a hint of what was to come. Many musicians today use 6/4, 3/4, 5/4, and far more complicated rhythms with the same freedom and skill with which variations on the customary 4/4 are tossed off. Drummers—notably, at first, Art Blakey and Max Roach—were the natural leaders of this development.

But it was a pianist Dave Brubeck who took over leadership in the extension of rhythmic horizons. As Dave's drummer, Joe Morello played a key role in winning a large public to what have remained a private enjoyment for under for musicians only. In this, his first album under his own direction, Joe clearly displays a number of the rhythmic devices for which he, as a member of the Brubeck Quartet, has become known. But - make no mistake - Joe’s first love is swinging and driving a band, whether small or large. So this album is indeed, “about time” - but the preoccupation with time never gets in the way of making swinging music.

Joe’s fantastic technique - probably the most overwhelming, ever - is never just for showing off. Throughout the record, he is heard as an integral member of the group; even his longest solo is actually an extension of what the band has been playing. That he is the member who provides most of the spark and drive for each performance is plainly evident at all times.

A basic small combo is heard throughout the album, with a brass ensemble added for four numbers (I Didn't Know What Time It Was, Every Time We Say Goodbye, Time on My Hands, and It's About Time). Manny Albam, arranger and conductor for these numbers, has integrated the combo so that there is frequently a concerto grosso quality to the sound of the ensemble.

Phil Woods, alto saxophonist throughout this set, is the arranger of five of the six remaining selections. Completing the album is a trio improvisation (Fatha Time) by pianist John Bunch, bassist Gene Cherico, and Joe.

Joe's approach, in assembling the musicians and asking Manny and Phil to write for them, was that the music must, at all times, swing. There was no attempt to use complex rhythms for their own sakes. The musicians, of course, had to be chosen with care. The principal soloists — Woods, Bunch, and vibraphonist Gary Burton — are strong "blowers." They are soloists of the type who dig in and go.

Woods, the best-known soloist, is one of the finest saxophonists of the post-bop era. He is a musician whose blazing musical temperament is perceptible even on ballads. Gary Burton is a teenage virtuoso who has bowled over seasoned musicians for the last two years and is just beginning to become known. He impressed Chet Atkins, RCA Victor's recording manager in Nashville (and one of the great guitarists of all time), so deeply that Chet promptly signed him. His first RCA Victor album will appear shortly. John Bunch, whose vigorous piano is sprinkled liberally throughout this album, is a youthful veteran of the Benny Goodman, Woody Herman and Maynard Ferguson bands, and has also played in the small combos of two of the country's most popular drummers, Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich.

As for more on Joe Morello — well, few people would be better qualified to tell you about him than Marian McPartland, with whose trio Joe sprang to fame—first with his fellow musicians, and then the jazz public.”

ABOUT JOE MORELLO BY MARIAN McPARTLAND

“Joe Morello is a drummer's drummer. As long as I have known him, which is close to ten years (when he first came to New York and sat in with me at the Hickory House in 1952), he has always been surrounded by drummers who came from all over to listen to him play, to talk to him, to work out or to study his amazing technique at close range. Joe joined my trio in 1953, and it was always interesting to me to see how much time he devoted to the study of the drums, even to practicing every spare minute between sets. He was absolutely fanatical about this, and at times there seemed to be a kind of controlled fury in his playing — sort of a fierceness which belies the appearance of this quiet, soft-spoken guy. Only when he plays does he reveal some of the inner conflicts and frustrations that have shaped and directed him in his restless drive for perfection.

Joe was a child prodigy on the violin, and can play piano quite well. He is a sentimental person who thinks deeply, who loves to daydream and to philosophize while listening to music—every kind of music. His musical tastes run all the way from Casals to Sinatra to Red River Valley. He is a complex person: on one hand, gentle, quiet and imaginative; then, in the next instant, a complete extrovert, doing impressions of his friends and laughing like a schoolboy; then again he becomes remote, moody, shut off from everybody in his own self-contained little world.

In the past few years Joe has traveled all over the world with the Dave Brubeck Quartet. He is now a seasoned performer, and shows the results and benefits of working with Dave. He has made a great reputation, and this is revealed in a different approach to his solos.

His musical ideas run along new lines; he uses his fantastic technique to better effect than ever, and he seems to have broadened his scope, not only in his playing but in various little intangible ways — in his increased confidence, in a certain gregariousness he never used to have. Yet, he is humble and at times almost disbelieving of his success. He has unquestionably made a great contribution to the Brubeck group, and I am sure that Dave would be among the first to agree that the success of tunes like Take Five, the Paul Desmond composition which put the Quartet on the nation's best-selling charts, is in some measure due to Joe's unique conception of unusual time signatures and his ability to play them interestingly.

The time is right for Joe, now one of the most illustrious sidemen in jazz, to record for the first time as a leader (although, of course, in public he is still the drummer of the Brubeck Quartet). For Joe, this has a very special meaning. It is not just an opportunity to perform with a hand-picked group of musicians, including his great friend Phil Woods as saxophonist and arranger. This album represents the fulfillment of a long-expressed desire which grew out of his first tentative experiments, as a boy, with a pair of brushes on the kitchen table in his home in Springfield, Massachusetts.

I believe that Joe was born to be a brilliant musician. This album will justify and renew the faith he has in himself, as well as the high praise and respect he has received from musicians all over the world. In discussing Joe recently, Buddy Rich called him "the best of the newer drummers; he has tremendous technique, and he is the only one to get a musical sound out of the drums."

The tunes and arrangements by Manny Albam and Phil Woods give him ample scope to express himself — whether with sticks on a hard-swinging, white-hot, uptempo tune such as Just in Time; or the delicate mimosa-leaf shading with brushes in Time After Time or Every Time We Say Goodbye.

In Joe Morello's playing you can hear the fire, the relentless drive, the gentleness, and the humor that is in him, and he has surrounded himself with some of the best musicians there are, to help him make this — his first album on his own — great.

Joe Morello - The Early Years

© - Steven A. Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“Everyone associated with the clinics is happy. "For every one that he does, I could book ten," said Dick Schory of the Ludwig Drum Company, Morello's sponsor. "There has never been a drummer who can draw people like he does, and he can keep them on the edge of their seats for two hours. He's a very good extemporaneous speaker, and he's such a ham that I'm sure he'd rather do this than play the drums. He razzles and dazzles them with his playing, and he has this fantastic sense of humor — it's not dry-as-dust lecturing — he makes it interesting, and he believes in it."

He will relax the crowd at the start of the clinic by kiddingly referring to it as a "hospital for sick drummers — and I'm the sickest of them all." Or "I guess all you people must need help or you wouldn't be here." Last year in London, at the first clinic there, he greeted deafening applause with, "If I'm elected, I promise ... ." After a particularly sizzling display, which had everybody on his feet applauding, he shook his head morosely and muttered, "I must be getting old."

But since I've been with Dave [Brubeck’s Quartet], I've had a lot of acclaim, and I'm very grateful for it. Some manifestations of that acclaim have been like dreams come true—you've never dreamed the dreams I've dreamed and had them come true! If I never do more than I have done already, I'm proud and happy for what I've accomplished — God has been good to me.”

- Joe Morello, drummer extraordinaire

The following feature on Joe Morello by Jack Tracy from the September 7, 1955 edition of Down Beat magazine may be the first about him to appear in a major Jazz periodical. I am still researching, but I have yet to find one that is dated earlier.

It is followed by two essays about Joe by pianist Marian McPartland in whose trio Joe performed from 1953-1956.

“JOE MORELLO is a big, shy, bespectacled drummer with the fastest hands this side of Buddy Rich and a too-modest appraisal of his own abilities, which are considerable enough to have won him this year's New Star award in the Down Beat jazz critics' poll.

He has been a member of the Marian McPartland trio for about two years now, in addition to spurring a number of record dates with such men as Tal Farlow, Gil Melle, Lou Stein, and John Mehegan.

His deft touch with brushes, his fantastically capable left hand, and the originality of his solos have earned him plaudits galore from musicians and close observers, and it appears that from now on he will be garnering considerable fan interest as well.

BUT IF JOE'S father had had his way, Morello would now be a violinist. He played that instrument for several years but then quit and wanted to begin on drums when he was 17.

His father practically threatened disinheritance, but Joe went ahead, and Springfield, Mass., now can lay claim to a man who could become one of jazz' most celebrated tubmen.

JOE WORKED AROUND Springfield for awhile with local groups and inevitably was drawn to New York, where he worked some off -nights at Birdland, spent some time with guitarist Johnny Smith, subbed for Stan Levey in the Stan Kenton orchestra for a couple of weeks, then joined Marian.

"It was the greatest thing that could have happened to me," says Marian. "Joe is the perfect sideman. He can play anything in any tempo, isn't a bit temperamental, and is just gassing everybody who heard him these days.

"When I went on the Garry Moore show regularly last year, it was Garry who insisted that Joe come along, too, even though it was originally planned that I do a single."

PERHAPS THE MAN who is most impressed by the talents of Morello, and one who raves about him every chance he gets, is his McPartland sidekick, bassist Bill Crow.

"He's great to work beside," says Bill. "Practices all the time. He keeps working on the idea of making extended solos a continuous line, just as if they were compositions. And more often than not, they're now coming off.

"I think there's only one guy around who still really scares Joe," he adds. "That's Buddy Rich. If Buddy is anywhere around, Joe will go in and sit for hours just to watch his hands and feet."

MORELLO READILY admits to his admiration for Rich, saying simply, "Buddy Rich is my drummer.

"Sonny Igoe is a great one, too. But I don't mean that I want to play like them. I just admire them for what they can do. I want to do something different. I think anyone who is serious about his instrument wants to be an individualist."

For a guy who has been playing drums only 11 years, and professionally for little more than three, he already has made remarkable strides in that direction.

And if the number of times his name keeps popping up in musicians' conversation about drummers is any indication, he will not be long in reaching his goal.

—tracy”

The Fabulous Joe Morello

Marian McPartland

All in Good Time

“The French they are a funny race. And drummer Joe Morello, who is of French extraction, does nothing to confound the maxim. His Gallic characteristics, combined with his quiet New England upbringing, seem to be at the root of his personality—high-spirited, full of fun, yet serious and sensitive to a marked degree.

In Joe Morello there is a dreamer who is nonetheless a down-to-earth realist; someone who is reserved yet outspoken; shy much of the time, yet frequently uninhibited.

These are not just characteristics that set Joe apart as a man. They also help to set him apart as a jazz musician—one who leaves critics and fellow workers alike raving about his fantastic technical ability, his taste, his touch, and his ideas.

Joe was born, brought up, and went to school in Springfield, Massachusetts. His father, now retired, was a well-to-do painting contractor who had come to the United States from the south of France. Joe's mother, who died when he was seventeen, was French-Canadian.

A gentle, music-loving woman who taught him as a small boy the rudiments of piano playing, she encouraged and fostered his obvious love for music. She saw that many of the pleasures others find in life would be impossible for Joe: his extremely poor vision prevented him from participating in most of the games and sports other children enjoyed. Music, she seemed to feel, was the best compensation—and perhaps much more than mere compensation.

When Joe was seven, his parents bought him a violin, and he began to show a precocious talent for and interest in music. Moody and withdrawn, he disliked school and made few friends. One friendship he did form, however, was with a neighbor, Lucien Montmany, a man who, crippled and confined to his home much of the time, took a great interest in the boy. He would play piano for him by the hour, and encouraged him to pursue music.

"Bless his soul, he was such a wonderful guy," Morello said. "And he helped me so much. He gave me confidence in myself, and after I had started studying drums, he used to say to me, 'Joe, you've got to practice all you can now, because you won't have the time later on.’

"And you know, he was right."

But Joe did not become interested in the drums until he was about fifteen. Until that time, he remained preoccupied with piano and violin—which explains in part the musicality of his work and his extreme sensitivity to other instruments.

He had made a few cautious forays into the rhythmic field. But these efforts were largely confined to performing with a couple of spoons on the edge of the kitchen table, as accompaniment to phonograph records. It irritated his parents and his sister Claire considerably.

But at last, with money earned from an after-school job in a Springfield paint shop, he bought himself a snare drum, sticks, and brushes and later—with money gained from the diligent selling of Christmas cards, among other things—the rest of the set. He found a teacher, Joe Sefcick, and began sitting in around town.

It was about this time that Morello formed a close friendship with another man who was to emerge as an important name in jazz: guitarist Sal Salvador.

"It was sometime in 1946 that I met Joe," Salvador recalled recently. "I was playing one of my first jobs when he came into the club with his father. He must have been about seventeen. I remember his father tried to get him to sit in, but he hung back.

"But finally he did agree to sit in, and he had very good chops even then. It was Joe Raiche's band. He was pretty well the king around Springfield, but we had heard talk about Joe Morello. And so he and Joe Raiche played some fours, and everybody thought he was great. I really dug what he did with the fours, especially since he was only playing on the tom-tom, and I asked him about working a job with me. After that we kept calling each other for jobs which we never seemed to get.

"From then on we were inseparable, we saw each other all day, every day."

Salvador tells several amusing stories that illustrate how much Joe (and several of his friends) wanted to play.

"Teddy Cohen, Chuck Andrus, Hal Sera, Phil Woods, and Joe and I would all get together and play as often as we could," he said. "Saturday afternoons we used to go to Phil's house. One day it was so hot that we moved the piano out onto the porch. Joe moved his drums out there, too. The weight was too much. The porch tipped! Everyone panicked.

"But Joe was the first to recover. And he was the first one back indoors, with his drums set up to play.

"We were so anxious to play that we'd set up and start things going just anywhere we could. Once we drove out to a club called the Lighthouse. But it was closed when we got there, so we set up and started playing, right in front of the place.

"Pretty soon the cops came and chased us away. I guess we kids just didn't think about what the grownups had to go through with us in those days ..."

Morello and Salvador continued working together at an odd assortment of jobs, including a radio broadcast, dances, and square dances. "Anything we could get," Salvador said. Then Morello started going to Boston to study with a noted teacher named George Lawrence Stone.

"I think it was Mr. Stone who finally made him realize that sooner or later he would have a great future in jazz," Salvador said. "And, of course, he gave Joe this great rudimental background. In fact, Joe became New England rudimental champion one time.

"In 1951, he joined Whitey Bernard. Finally, after working on the road with him, he went to New York in 1952 and put in his union card. I had gone there and had been begging him to come for some time. But he would say, 'No, I'm not ready yet. There are too many good drummers there.’

"However, he finally made it, and as you know, the Hickory House was one of the first places that he and I came to, to hear your group."

From here on, Joe Morello's story becomes quite personal to me.

At the time, there was a constant swarm of musicians at the bar of the Hickory House, where I was working. Sal had often told me about this "fabulous" drummer from Springfield. But being so accustomed to hearing the word "fabulous" used to describe talent ranging from mediocre to just plain bad, I was slightly skeptical.

But one night Joe came in with Sal. Mousie Alexander, who was playing drums with me at the time, introduced us. Joe Morello, a quiet, soft-spoken young man about twenty-three, looked less like a drummer than a student of nuclear physics. Yet I was, after hearing so much about him, eager to hear him play.

We got up on the stand, Joe sat down at the drums and deftly adjusted the stool and the cymbals to his liking. And we started to play.

I really don't remember what the tune was, and it isn't too important. Because in a matter of seconds, everyone in the room realized that the guy with the diffident air was a phenomenal drummer. Everyone listened.

His precise blending of touch, taste, and an almost unbelievable technique were a joy to listen to. His technique was certainly as great (though differently applied) as that of Buddy Rich. And through it all, he played with a loose, easy feeling interspersed with subtle flashes of humor reminiscent of the late Sid Catlett.

That is the way Joe sounded then, and I will never forget it. Everyone knew that here was a discovery.

Word of his amazing ability spread like fire among the musicians, and soon he was inundated with offers of work. It was not long afterwards, following a short period with Stan Kenton's band and some dates with Johnny Smith's group, that Joe became a regular member of my group.

We opened at the Blue Note in Chicago in May 1953 and later returned to the Hickory House.

Every night it was the same thing: the place was crowded with drummers who had come to hear Joe.

He practiced unceasingly between sets, usually on a table top, with a folded napkin to deaden the sound and prevent the customers and the intermission pianist from getting annoyed. Sometimes the owner would walk over and say irascibly, "Stop that banging!"

But usually no one bothered him, and he gave his time generously to the drummers who came to talk with him. Soon he had some of them as pupils.

And wherever we played, it was the same. Young drummers appeared as if by magic, to listen to Joe and talk to him and to study. They arrived at all hours, in night clubs, at television studios, in hotels. We called them "the entourage." Several of them now are playing with top groups in various parts of the country.

During this period, Joe, bassist Bill Crow, and I started doing a lot of television, and recorded several LPs for Capitol. Nineteen-fifty-five was a good year for us. We received the Metronome small group award, and Joe won the Down Beat International Critics poll new star award. It was presented to him on the Steve Allen Show.

About that time, Joe and Bill were making so many freelance record dates that I told them I thought I should open an office and collect 10 per cent!

Some of Joe's best work was done on those sessions. At least, the best I have heard him play. There is a wonderful recording that he and Bill made with Victor Feldman and Hank Jones which, unfortunately, never has been released.

But there are other albums in which you can hear Joe at this period. One was an album done by Grand Award, with a group led by trombonist Bob Alexander. Chloe is easily the finest track. There's an interesting vocal and drum exchange with Jackie Cain and Roy Krai in a piece called Hook, Line and Snare in an album they did together. And he recorded some sides with my husband Jimmy and myself. This was more on the Dixieland kick, which points up Joe's extreme flexibility.

There are also some wonderful sides Joe made with Gil Melle, Sal Salvador, Sam Most, Lou Stein, John Mehegan, Tal Farlow, Helen Merrill (with Gil Evans' arrangements), and with Jimmy Raney and Phil Woods.

Alas, though for a time he turned down all offers, I was not to keep Joe with my group forever. And when I lost him as my drummer, my one consolation was that he was going to join a musician whom I respected very deeply: Dave Brubeck.

Joe joined the quartet in October 1956. Since then he has gone on growing.

Indeed, his playing has altered considerably, partly because of his fanatical desire for improvement and change, partly because the kind of playing Dave requires from a drummer is different from the techniques that Joe used with my group.

With me, Joe had concentrated more on speed, lightness of touch, and beautiful soft brush work. Dave, both a forceful personality and player, requires a background more in keeping with his far-reaching rhythmic expositions, and someone who can match him and even surpass him on out-of-time experimentation.

Today, Joe, though a complete individualist, hews closely to Dave's wishes as far as accompaniment is concerned. But he cannot help popping out with little drummistic comments, subtle or explosive, witty or snide — depending on his mood at the moment.

It is Dave's particular pleasure to go as far out as possible in his solos, and have the rhythm section carry him along. For this reason, the drummer must have a very highly developed sense of time and concentration to keep the tune moving nicely while these explorations are under way.

Bassist Gene Wright and Joe — "the section," as they refer to each other — do this most ably. Wright's admiration for Joe is unbounded.

"There's never been any tension at all from the day I joined the group," he said. "Joe makes my job very easy. We play together as one, and when a drummer and bass player think together, they can swing together. As a person, he's beautiful, and it comes out in his playing.

"There are no heights he cannot reach if he can always be himself and just play naturally. His potential is far beyond what people think he can do, and he'll achieve it some day."

Like any musician, Joe has detractors, those who can be heard muttering to the effect that he's a great technical drummer but doesn't really lay down a good beat — or, in more popular parlance, "He don't swing, man." But these detractors are remarkably few, and Brubeck is vehement in saying, "They're out of their minds!"

"Joe swings as much as anybody," Dave said, "and he has this tremendous rhythmic understanding. You should have heard him over in India with the drummers there. They just couldn't believe an American drummer could have that kind of mind, to grasp what they were doing. They said it would probably only take him a little while to absorb things it had taken them a lifetime to learn.

"As it is, Joe assimilates things quicker than any jazz musician I know, and he has the biggest ears. He was able to do many of the things the Indian drummers were doing, but they couldn't do what he does because they're just not technically equipped for it.

"How has his playing affected my group?

"I would say we have a better jazz group since Joe joined us. He really pushes you into a jazz feeling. And in his solos, when he gets inspired, he does fantastic things. Sometimes he gets so far out it's like someone walking on a high wire. Of course, he doesn't always make it, and then he'll say, "Oops!" But then he'll come right back and do it next time around. He is a genius on the drums."

Paul Desmond is just as forthright in his comments about Joe. "Joe can do anything anybody else can do, and he has his own individuality, too," Brubeck's altoist said. "Do we usually play well together? Yes, unless we're mad at each other! Naturally there are times, as in any group, when there might be a little difficulty of rapport if we are feeling bad. Playing incessantly, the way we do, night after night, it's almost impossible once in a while not to be bored with each other and with one's self. This is never true of Joe, especially on the fours."

I asked Paul how he felt about the rave notices that Joe has been getting since he joined the group.

"Well, Dave and I have been on the scene for about ten years now," he replied, "and it's only natural that somebody new, especially a drummer as good as Joe, would rate the attention of the critics. He definitely deserves all the praise he is getting. I think he's the world's best drummer, but it's his irrepressible good humor on and off the stand that I dig most of all."

Similar views were shared by a good many other persons, among them Joe's friend and long-time co-worker at the Hickory House, bassist Bill Crow, though he expresses it a little differently.

He always has amazingly precise control of his instrument at any volume, at any tempo, on any surface, live or dead. He's very sensitive to rhythmic and tonal subtleties and has a strong time sense around which he builds a very positive feeling for swing. Extraordinarily aware of the effect of touch on tone quality, he uses his ears and responds with imagination to the music he hears associates play.

With these assets, I nevertheless feel Joe isn't a finished jazz drummer, considering his potential. He can play any other kind of drum to perfection, but I don't think he's saying a quarter of what his talent and craftsmanship would inevitably produce if he were playing regularly with musicians who base their rhythmic conception on the blues tradition.

I know that Joe is attracted to this tradition, uses it as a focal point in his establishment of pulse, and feels happiest when he is playing with musicians who work out of this orientation. But he has never yet found a working situation where anyone else in the band knew more than he did about the subtleties of it . . .

He still has to find an environment that would demand response and growth on a deeper level. He needs to solve the problems presented by soloists like Ben Webster, Sonny Rollins, Harry Edison, or Al Cohn. He has to discover from his own experience how the innovations of Dave Tough, Sid Catlett, Kenny Clarke, or Max Roach can be applied to various musical situations. But primarily, he needs to play with Zoot Sims-type swingers who will reaffirm his feeling for loose, lively time.

Now that Joe's home base is San Francisco, he and his wife Ellie (they were married in 1954 while we were playing at the Hickory House) maintain an apartment in town. They have formed a close friendship with Ken and Joan Williams, owners of a San Francisco drum supply shop where Joe teaches every day he's not on the road and where he practices incessantly. The feeling his pupils have for him is nothing short of hero worship, and his opinions and views are digested word for word.

As Sam Ulano, a noted New York drum teacher puts it, "One of the great things Joe has done to influence the young drummers is to make them more practice conscious. He has encouraged them to see the challenge in practice and study, and I think it is important, too, that people should know how Joe has completely overcome the handicap of poor vision to the extent that few people are even aware of it. This disability has acted as a greater spur to him, already filled as he is with deep determination to perfect his art, and others with similar problems can take note and gain hope and encouragement from it."

A conversation with Joe, no matter on what subject, invariably comes back to a discussion of music in one form or another. Musicians for whom he has veneration and respect range from veteran drummers Gene Krupa and Jo Jones to pianists Hank Jones, Bill Evans, and John Bunch. Phil Woods is one of his favorite horn players, and he admires Frank Sinatra, Peggy Lee, Anita O'Day, and Helen Merrill. His tastes in music run from plaintive gypsy violin music to the Brandenburg concertos.

Joe confesses to a dream for the future of having his own group. He would like to have his long-time friend, altoist Woods, in it.

But I'm not really ready for this yet. What I'd like to do right now is to develop greater facility, plus ideas, and improve my mind musically. To have basically good time—that's the first requisite, of course. Taste comes with experience. Then, too, you must have a good solid background to enable you to express yourself properly.

This is one of the things Mr. Stone did for me when I studied with him, and I owe him a great deal. He taught me how to use my hands. My idea of perfection would be good time, plus technique, plus musical ideas. Technique alone is a machine gun! But it sure brings the house down.

Years ago I was impressed by technique more than anything else. I think what made me go in for this so much when I was working with you, Marian, was that I was shocked by the lack of it in the New York drummers. I didn't realize at the time that a lot of them might be thinking more musically and developing along other lines. Now I listen for different things and I try to think of a musical form in my solos—a musical pattern. And when you know you're right, and it feels good to you— without sounding mystical or corny, sometimes things just come rolling out—building and building—a sort of expansion and contraction, you know? Now, take Buddy (Rich). If you want to use the term great, he's great. And Shelly (Manne)—I admire him very much and Louis Bellson, too.

Years ago Joe Raiche and I went to see Louis at Holyoke, and we invited him back to the house. I'd started experimenting with the finger system, but he really had it down, and as we sat at the kitchen table and talked, and he showed me some things. I sometimes think I played better in Springfield than I do now, though I've learned an awful lot from playing with Dave and Paul [Desmond], and Dave's such a good person to work for.

Being with this group is a marvelous experience for me. I'm grateful for the freedom Dave gives me, and he does give me plenty, both in concerts and on the albums. Working with him is interesting because he's very strong in what he believes in. But then so am I, and we both know this. So we respect each other's views, and we compromise—each of us gives a little. And as Dave said to you, we've found a point of mutual respect and understanding. We know we don't agree completely, and yet we can go on working together and enjoying it.

There's so much to be done — if you've got the mind and the imagination. That's what the drummer needs — the mind! And talent? You know what that is? It's 97% per cent work and 2 % per cent b.s.

I want to be as musical as I can — play the best I can for the group I'm with — and be myself. If I can do that, then I'll be happy.

Joe Morello: With A Light Touch

Marian McPartland

All in Good Time

“Joe Morello is a man of many natures. Restless, quiet, at times effervescent, at others the life of the party or completely aloof. Like the dark side of the moon, there is much about him that is unknown to most persons, perhaps even to himself. Yet he is also naive and funny. One moment, he will exclaim, with a schoolboy grin, "I feel like a sick sailor on the sea of life." Two minutes later, he will mutter moodily, "I should have been a monk." One could use a divining rod, sextant, sundial, geiger counter, and crystal ball to anticipate—and keep track of—the many verities of his nature.

To many young drummers, he is like a savior. Accordionist-organist-singer Joe Mooney calls him the well-dressed metronome. To his detractors he is merely a gifted drummer, an exceptional technician who can be hostile, even arrogant, at times. He has been called a prima donna, whose mood can change from animation to black despair without notice.

But people who know him well know, too, that he is also gentle, idealistic, and sensitive, a searcher for something he cannot name, who daydreams dreams, many of which already have come true.

"Do you know—I'm the only drummer who ever won the poll who doesn't have his own band?"

Morello says that with a big grin. Having made a clean sweep of most jazz popularity polls three years running — including Down Beat's Readers Poll—one would imagine he is delighted with the way things are going, especially since he has the salary and prestige of many a leader, with few of the responsibilities. Possibly the highest paid and certainly one of the most respected and admired drummers in the country, he can afford to smile.

"I've been lucky," he says. But anyone who knows Morello knows well that hours of practice, rigid discipline, and a continuing pursuit of perfection have had more to do with his current eminence than simple luck.

Further goals are pictured clearly in his mind's eye: "I can always see that straight line, and then I know I'm right."

Joe has been guided in this intuitive fashion many times, first perhaps when he decided to give up violin in favor of drums, overruling his father's original wish that he should become a painting contractor. Later, he decided to go to New York City ("I told my father I'd give myself six months to make good — if I didn't, I was going to go back to Springfield"). Later still, he joined my trio and while with it from 1953 to 1956 started to build the reputation he now enjoys. With growing confidence, he felt ready, in 1956, to join Dave Brubeck, with whose quartet he has established himself as a percussion virtuoso.

The publicity and acclaim he has received over the last nine years has been of inestimable value to him, for Joe, outstanding as he is, needs a showcase for his talents, and Dave has been more than generous. Dave has shared his spotlight with Joe and given him ample solo space. No leader could have been more considerate.

Though undoubtedly grateful, Joe has made full use of the spotlight, even to the extent of some artless scene-stealing— twirling the sticks, shooting his cuffs during a piano solo, delicate sleight of hand with the brushes, and other diversionary tactics.

However, Joe is probably the one drummer who has made it possible for Dave to do things with the group that he would have had difficulty accomplishing otherwise. Joe's technique, ideas, ability to play multiple rhythms and unusual time signatures, humor, and unflagging zest for playing is a combination of attributes few other drummers have. All these in addition to his ability to subjugate himself, when necessary, to Dave's wishes yet still maintain his own personality.

Joe is fascinating to watch play — he may have several rhythms going at one time, tossing them to and fro with the studied casualness of a juggler. Yet through it all, the inexorable beat of the bass drum (not loud—felt more than heard) holds everything together. He moves gracefully, with a minimum of fuss, but with a sparkling, diamond-sharp attack, reminiscent of the late Sid Catlett.

Sometimes a quick, impish grin comes over his face as he plays a humorous interpolation, and then he looks for all the world like a small boy throwing spitballs at his classmates. Though he seems withdrawn—remote at times—his movements are so expressive that when he breaks into a smile and glances around at Gene Wright, the group's bass player, one can sense his pleasure and can be a part of it.

Despite Joe's varying emotions and changing moods, there is one thing about him that never changes, except to grow stronger: his love of playing. This love is reflected in everything he does, his approach to life, to people, to himself.

As long as I have known Joe, he has had fine musical taste, technical control, and a light touch "delicate as a butterfly's wing," to quote Dave Garroway, and though he plays a great deal more forcefully with Brubeck than he did with my trio, still the lightness is there most of the time.

"Underplay if possible," he told me recently. "If you start off at full volume, you have nowhere to go. Be considerate of the other members of the group — drums can be obnoxious or they can be great."

Where Joe is concerned, it is invariably the latter. I have never heard him play badly.

Now that he is, in the eyes of many, the No. 1 drummer in the country, he could be the man to change the course of current drumming. In this era, when sheer volume appears to be the criterion for percussion excellence, when the artisan has apparently been replaced by the unschooled, Joe Morello stands out as something of a phenomenon. He is not an innovator, but he draws from the styles of drummers past and present whom he has observed and admired to produce a sound, a touch, a feeling that is essentially his own.

He has been criticized rather than praised by some of his peers, who tend to enjoy a barrage of sound, crudely produced, rather than the finesse, delicacy, and range of dynamics that Joe draws from drums. Nevertheless, it may be that he is, in the words of drum manufacturer Bill Ludwig, "an apostle — someone who can preach the word to all the kids coming up, show them how to play the drums properly, how to play cleanly, to direct their studies and their talents to the most musical approach to the drums possible."

In the last few years, he has had opportunity to talk with novice and would-be drummers and to show them some of his ideas.

They crowd around him after concerts. They dog his footsteps in hotels. They gather in dining rooms and coffee shops. Joe also gets three months a year off from the Brubeck group and travels the country to appear at drum clinics in schools, music stores, and auditoriums for the benefit of the local drummers, students, and teachers.

The clinic idea is not new, but Joe has brought a different dimension to it. From being a comparatively small operation, in which possibly a hundred persons would come to see a name drummer play a solo and perhaps give a short talk, clinics are now getting to be big business. When Joe appears at one, the hall is invariably jammed; if the room holds five hundred, another two hundred are turned away. Last year Joe pioneered the clinic idea in several European countries— England, Holland, Germany, and Denmark. More recently he has brought drum clinics to Puerto Rico. This year, he will give clinics in new territory—when the Brubeck quartet goes to Australia, New Zealand, and Japan.

Everyone associated with the clinics is happy. "For every one that he does, I could book ten," said Dick Schory of the Ludwig Drum Company, Morello's sponsor. "There has never been a drummer who can draw people like he does, and he can keep them on the edge of their seats for two hours. He's a very good extemporaneous speaker, and he's such a ham that I'm sure he'd rather do this than play the drums. He razzles and dazzles them with his playing, and he has this fantastic sense of humor — it's not dry-as-dust lecturing — he makes it interesting, and he believes in it."

He will relax the crowd at the start of the clinic by kiddingly referring to it as a "hospital for sick drummers—and I'm the sickest of them all." Or "I guess all you people must need help or you wouldn't be here." Last year in London, at the first clinic there, he greeted deafening applause with, "If I'm elected, I promise ... ." After a particularly sizzling display, which had everybody on his feet applauding, he shook his head morosely and muttered, "I must be getting old."

Joe usually divides the two-hour lecture into several parts— first describing his drum setup, what size the drums are and why he uses them. Once in a while, he will do impressions of well-known drummers with devilish accuracy. Sometimes he plays a short but hilarious solo, doing everything wrong, to expose areas in which a drummer could improve. He answers questions tirelessly and takes great pains to make sure that everyone has understood his meaning, going over a point several times if necessary.

I’d like to have him do these clinics all the time," Bill Ludwig said. "He's a natural teacher, and he's at his best with kids. Nothing is too much trouble — he loses himself in it. This is the answer to the uneducated drummers of today— show them what real study is.

"As far as actual talent is concerned, there hasn't been anyone quite like him — no one who has this devotion to the instrument. And he's such a gentleman.

"He has brought realism to the clinics; he's not just a performer who will pass the two hours giving a technical demonstration. This guy opens his heart and says, 'Here it is, use it, free.' I've seen clinicians who would spend two hours showing off their dexterity, but Joe does things that are useful to the students."

One can only guess at Joe's feelings about this acclaim. It surely has not changed his attitude toward his work. He has never let up. When at home, it's still practice, practice. He seems to derive comfort from this, almost as if the drums were a refuge where he feels secure and can gain reassurance.

The standing ovations, the adulation of laymen and musicians alike, contribute to his well-being. But his real satisfaction comes from the clinics. With every patient explanation of a point to a student, he gives something of himself, and the effects of it are more gratifying than the concert applause. He gives the best that is in him with a forthright and unequivocal stance.

Many people in music believe that Morello's major contribution to music is yet to come — certainly as a teacher and perhaps with his own group. Many possibilities are open to him. Currently, few musicians think of him solely as a jazz drummer; most look upon him as a drum artist, because much feeling still exists that he is not really a hard swinger. This may be a carping criticism, but it appears that his work with Brubeck seems to call for just about every kind of playing but "hard swinging." There are some good grooves, but the constantly changing, fluctuating rhythms of 5/4, 9/8, and so on (as well as those Dave imposes on the rhythm section in his solos) impede any steady swinging.

When Joe goes "moonlighting" and sits in with different groups (he recently played a set with Dizzy Gillespie and gassed everybody), he is almost like a racehorse that has been allowed to run free after being reined in; and on these occasions, he proves again that he can swing strongly when he is among hard cookers. Then his playing takes on a different quality. It becomes more uninhibited, more relaxed.

A chat with Joe, no matter how it starts, almost invariably ends as a discussion of music in one form or another. Sometimes he gets so wound up that it's more like a filibuster. Never one to hold back, he will animatedly discuss the modern drummer:

Those things they are playing today . . . Max Roach did that beautifully years ago

— Roy Haynes, too (in fact when Bob Carter and I were with you, Marian, we did that same thing—sort of conservatively). But when I see a guy take the butt end of the sticks . . . when I have to guess where the time is, I could cry. Who's going to play against that? Funny—some sixteen-year-olds are digging it! When I was sixteen, I listened to Krupa, Buddy Rich, Max [Roach], Jo Jones.

This whole thing apart, any drummer should be able to play time. These kids coming up ... they have a choice. Some of them may blow it, but some of them are going to come along and make everybody look like punks.

You know, Marian, you used to say my playing was too precise, but I really think I'm beginning to play more sloppy now. But I'm continually trying to get myself together and play something different, and one thing Dave has taught me — that's to try to create. I admire him harmonically, and you just can't dispute the fact that he plays with imagination. Oh, he's not always the easiest guy to play with, but he's so inventive. . . .

Years ago, I wanted to play like Max, but then I found out you've got to develop your own style . . .good or bad, it's me. But I can't play well all the time — I'm not that consistent. Like, I don't expect to be happy all the time either ... everyone's been disappointed. But since I've been with Dave, I've had a lot of acclaim, and I'm very grateful for it. Some manifestations of that acclaim have been like dreams come true—you've never dreamed the dreams I've dreamed and had them come true! If I never do more than I have done already, I'm proud and happy for what I've accomplished — God has been good to me.”

Joe Morello - The Later Years

© - Steven A. Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“See, playing is an individual thing, and boy, I'll tell you, I respect anyone who can play. Anyone who has a reputation has earned it. I'm sure there are people who disagree with my playing, and there are some who think I'm the greatest thing that ever happened. That's what's so great about an art form. It would be awfully boring if everyone played the same. If everyone sounded like me, or like Elvin, or like Max Roach — what a drag. You would only have to own one record. It's individual. You can't like everybody. I certainly don't like every drummer I hear. I appreciate if someone has earned any kind of reputation, but I prefer certain people over others.”

- Joe Morello, drummer extraordinaire

"George Lawrence Stone used to say, ‘The secret to failure is to try to please everybody.’ You can't. I went through a period where I tried, and I used to get really upset. After a while, you realize that you can't please everyone. Another of Stone's little axioms was, "The secret to success is an unbeaten fool." I asked him what that meant, and he said, "It means you're too dumb to quit." [laughs] You'll be criticized and put down, but you keep coming back and trying again."

- Joe Morello, drummer extraordinaire

The editorial staff of JazzProfiles now concludes it’s series of presentation on drummer Joe Morello with a posting of this extensive interview that Rick Mattingly conducted with Joe for the November 1986 edition of Modern Drummer.

“I’ll never forget one night about three years ago when I went to Joe Morello's home to work on the text for his book Master Studies. We were going over the section dealing with ostinatos, and Joe was playing one of the exercises: 8th notes with an accent pattern.

"Once you get this happening with your right hand," he explained, "you can play whatever you want against it with your left" whereupon he began to play sevens with his left hand. I had been working with the ostinato section myself, and I was finding it a challenge to play anything with the left hand without losing the accent pattern in the right, so it was somewhat irritating to watch Morello playing sevens against the ostinato with no apparent strain.

And so I said — somewhat sarcastically, I must confess — "Yeah, and then you could play triplets on the bass drum." In all innocence Joe replied, "Sure, you could do that," and began tapping his right foot in triplets along with what his hands were doing. And then, as if to add insult to injury, he said, "Of course, when you do stuff like this, you should keep the hi-hat going," with which he proceeded to tap out 2 and 4 with his left foot.

I'm by no means the first person to have a run-in with Morello 's formidable technique. Jim Chapin likes to tell stories about Joe at the Hickory House in the '50s. It seems that he would approach various big-name drummers and ask them to demonstrate certain techniques. After observing what the person did, Joe would ask, "Is this it?" and play it back twice as fast. When confronted with this story, Morello admits that it happened but offers an explanation. "I know it sounds like I was being a wise guy, but actually I was just naive. I came to New York in awe of all these drummers I used to read about, and I assumed that they knew a lot of things that l didn 't. When they would show me things, I thought that they were just playing them slow so that I could see what they were doing. I gradually came to realize that some of those people really didn’t have a lot of technique."

Joe, however, was fascinated with technique, and to this day he has continued to study and develop it. But to dismiss Morello as a mere technician is to miss the point of his musicality. As his landmark recordings with the Dave Brubeck Quartet amply prove, Joe's technique is merely the vehicle that is used to carry his ideas. Perhaps Joe's mentor, the great George Lawrence Stone, expressed it best in a letter he wrote in 1959: “‘I consider him to be one of the finest and most talented executants I have ever heard. I am indeed proud of him. In addition to the more obvious attributes of speed and control, he has a most highly developed sense of rhythm and that feeling of (and for) jazz, without which all other endowments fail.

In other words, to put it crudely, he possesses that uncanny sense of 'putting the right sound in the right place at the right time.'"

Rick Mattingly: You have spent many years developing extraordinary technique, and people have asked you, "Where are you going to use this stuff?" What is your answer to that question?

Joe Morello: I suppose you don't really need it. My feeling is that the technique is only a means to an end. It opens your mind more, you can express yourself more, and you can play more intricate things. But just for technique alone—just to see how fast you can play — that doesn't make any sense. In other words, technique is only good if you can use it musically. It's also useful for solos, so you can have the freedom to play what's in your mind.

When you're playing on the drumset, you don't say, "I'm going to play page 12 in the such-and-such book." You just play from the top of your head, but you know that, if you're going to go for something, nine times out of ten it will come out. The players who have limited facility don't want to take chances because it won't happen. I can see it from teaching drummers who have been playing for a long time. We'll play fours together, and they'll struggle to get something simple out. I'll say, "Look, I know what you're trying to do, but you blew it because you don't know the instrument that well." The more control you have of the instrument, the more confidence you will get, and the more you will be able to express your ideas. That's basically it. Technique for just technique alone — forget it. If you can't use it musically — if you're just going to machine gun everyone to death—that's not it.

RM: Obviously you've spent more time than most really looking into the subtleties of technique. Do you remember what it was that got you so interested in exploring technique to the extent that you explored it?

JM: Originally, I wanted to be a classical drummer— classical snare drummer and timpanist and the whole thing. This was my whole bit. Before that, I played the violin from when I was five years old until I was about 11 or 12. Then I heard Heifetz, and after that, I wasn't happy with the way I played. But I always liked the drums, and I always could play those little corny things like any kid did with pots and pans. Then I studied with Joe Sefcik in Springfield—a vaudeville drummer. My father didn't want me to study drums at all. He got sick of paying for violin lessons, so he said, "If you do anything, you'll have to do it on your own.'' So I used to go down to the vaudeville theater every week, see the movie, sit right in the front, and I got all Sefcik's brush beats down. All that stuff came easy to me.

Meanwhile, I was listening to Gene Krupa. Sefcik told me about him, so I picked up on some of his things, caught him in person a few times, and I was impressed with that. I liked the big bands and that whole thing, so I started collecting records. I listened to Basic's band with Jo Jones, and then one day I heard Tommy Dorsey with Buddy Rich. There was this blaze of triplets and this driving kind of thing that just knocked me out. I had never even heard of Buddy Rich. I started listening to more of the Tommy Dorsey things and researching that.

That, I think, was an inspiration. I said, "That's really the way I want to play." I was only 15 or 16. So that was my main inspiration to see how far I could take it. I always felt that, if one person could achieve a facility like that, anybody could if he or she wanted to.

RM: I find it interesting that hearing people like Buddy Rich inspired you to go after technique. But when you searched it out, your teachers were not jazz drummers like Buddy Rich, but people like George Lawrence Stone and Billy Gladstone.

JM: That's right—exactly. I'm glad you brought that up. See, when I went to Stone, I thought it was kind of fun just to bang around on the drumset, but I never really took it that seriously. I wanted to do all the classical things with Stone. We were working on that, and then I wanted to go on timpani and xylophone. He said no. It was like the rude awakening. He said, "Joe, you don't see well enough. When you play timpani or mallets, the music is too far away. You also have to watch the guy with the stick. Look, Krupa studied with me. He's innovative. You've got that same thing. Why don't you try that route?'' It really kind of hurt my feelings, because I wanted to be up there with the tuxedo and the long tails playing very serious music.

RM: You could have joined the Modern Jazz Quartet.

JM: [laughs] Yeah, but I thought classical music was where it was at. So I went along with Stone's idea, and I started thinking along those lines. That was about the time that I heard Rich and Krupa; I’d listened to Krupa before then, but I figured I'd | never really be able to do that. I listened to Buddy 5 for his powerhouse kind of playing with the Dorsey band. Then I started listening to people like Sidney Catlett, J. C. Heard, and then, of course, Max Roach and Kenny Clarke. Max influenced me a lot, because he used the technique in a linear way, rather than strictly a speed kind of thing. He played little melodic phrases, and I try to incorporate that in my playing, whether it's obvious or not. I like to do little speed things at the end, but I've got to do the playing first. Roy Haynes, too, influenced me a lot. He's probably one of the most creative drummers I've ever heard. I think he's fantastic.

So these are basically my roots, and the things I started listening to and developing. I think I've taken a little bit here and a little bit there, and put it together in my own way like everyone does. When I was a kid, I used to do great imitations of solos like the ones Gene did. Then we had a group in Springfield in my formative years. It was Sal Salvadore, Phil Woods, Hal Sera on piano, and Chuck Andrus on bass. We would have jam sessions and imitate everybody. Phil would play all the Bird licks, and I would play all the Max Roach things. It was Sal and Phil who really pushed me to go to New York. I had a rough time when I first went there, but a couple of drummers like Mousey Alexander and Don Lamond were very encouraging to me.

RM: During the era you came up in, most of the technique-oriented drummers, like Rich and Krupa, were associated with big bands. Why did you choose to go the small-group route?

JM: When I came to New York City, basically big bands were on the way out. Before I went with Marian McPartland, I was playing with Johnny Smith's group and I got the call to do the Stan Kenton thing, because Stan Levey had to go back to Philadelphia for some operation—his appendix or whatever. So I went to speak with Stan, and he said, "You've got the job." I said, "You never heard me play." He said, “I’ve heard enough people talking about you. I know you can do it. Shelly [Manne] talked about you." So I went with the band for about three-and-a-half weeks. I enjoyed it. By the first three or four days, I had the whole book down. I loved it. I could really play out. That was a loud band.

Anyway, after that, Marian McPartland hired me, and I stayed with her for three years. Then Bellson came in to see me at the Hickory House. He was leaving Dorsey to go out with Pearl Bailey. He said, "Why don't you audition for the band? Tommy's been through about 50 drummers, and none of them cut it." They were playing bebop drums with a big band, which didn't make it. Dorsey wanted someone who could play the solid bass drum and all that. Of course, I grew up listening to that band; I knew most of his tunes. So I went down to the Cafe Rouge, sat in with the band, and Tommy liked it. "It was great. You've got the job.'' They

were doing summer replacement for the Jackie Gleason show. I told him that I had a little difficulty reading. He said, "Don't worry, as long as you can see me out front," which I could. But the manager was playing games, so that thing didn't go through because of the financial thing. The manager was really trying to do a number on me, but Tommy didn't know that.

Then the Goodman thing came up. I was still with Marian. Benny Goodman wanted to get a band together, and he was going to do a tour of Europe or something. So Hank Jones called me and said, "Why don't you audition with the band?" They were auditioning guys like Gus Johnson, who had just left Basie's band. I figured, "Man, if they don't like him, what are they going to think of me? " So I went down and played with Benny. It was a typical Benny Goodman rehearsal — just Hank Jones and I, with just a snare drum, a pair of brushes, and a cymbal. So in comes Benny with a little hat on and a clarinet. He didn't say a word — the usual. That's a whole book in itself talking about Benny. So he wanted me to go with the band, but he was rehearsing at 9:00 in the morning, and I was working at the Hickory House until 4:00 A.M. and wouldn't get home until 4:30. I made a few rehearsals, but we were playing these old charts, and I told Benny, "I don't think I sound good with this band." His answer was, "It's not you, kid. We can keep time. The band can't." So he'd stop and rehearse the saxes and trumpets without a rhythm section. Anyway, that didn't work out.

So then around that same time, I got a call from Brubeck. All at once everything was coming down — all these bands. He was working over at Birdland, and he wanted to talk to me. We met at the Park Sheraton Hotel. He started telling me that he wanted to make changes. He and Paul Desmond had been coming into the Hickory House and seeing me play. He liked my brushwork, so he offered me a situation. At first I said, "Well, I really don't know if I'd sound good with your group, because the drummer you have just stays in the background. The spotlight is on you and Paul, and the drummer and bass player hardly ever get mentioned. I never heard a four-bar break from the guy." That was Joe Dodge — a nice man. He said, "No, I'll give you all the freedom you want. I'll feature you in the group." This was around July. He said, "Can you join the group in October?" I said, "I guess so." He said, "When I get back, I'll send you a telegram, and then you send me a telegram of confirmation." So I did.