© -Steven Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“What I am about to do really can't be done at all, and that is to do justice to Sarah Vaughan in words. Her art is so remarkable, so unique that it, sui generis, is self-fulfilling and speaks best on its own musical artistic terms. It is—like the work of no other singer—self-justifying and needs neither my nor anyone else's defense or approval.

To say what I am about to say in her very presence seems to me even more preposterous, and I will certainly have to watch my superlatives, as it will be an enormous temptation to trot them all out tonight. And yet, despite these disclaimers, I nonetheless plunge ahead toward this awesome task, like a moth drawn to the flame, because I want to participate in this particular long overdue celebration of a great American singer and share with you, if my meager verbal abilities do not fail me, the admiration I have for this remarkable artist and the wonders and mysteries of her music.

No rational person will often find him or herself in a situation of being able to say that something or somebody is the best. One quickly learns in life that in a richly competitive world—particularly one as subject to subjective evaluation as the world of the arts—it is dangerous, even stupid, to say that something is without equal and, of course, having said it, one is almost always immediately challenged. Any evaluation — except perhaps in certain sciences where facts are truly incontrovertible — any evaluation is bound to be relative rather than absolute, is bound to be conditioned by taste, by social and educational backgrounds, by a host of formative and conditioning factors. And yet, although I know all that, I still am tempted to say and will now dare to say that Sarah Vaughan is quite simply the greatest vocal artist of our century…."

- Gunther Schuller’s tribute to Sarah Vaughan which preceded a Vaughan concert at the Smithsonian Museum in 1980.

Too much of a good thing?

Never when it comes to Sarah Vaughan.

I had heard her on records, but nothing prepares you for the astounding brilliance that comes across when you hear her in person.

In Sarah’s case, “astounding brilliance” is not hyperbole; if anything, it is an understatement!

In the summer of 1962, I was working a piano-bass-drums trio gig in the North Beach area of San Francisco, just down the street from Sugar Hill where Sarah was appearing with her trio [the Jazz Workshop was also nearby].

On my first set break, I headed down the street to checkout what was happening at the Jazz Workshop when I pasted the entrance of Sugar Hill and heard Sarah doing her thing.

I explained to the person collecting the cover charge at the door that I was a musician working up the street and asked if I could step inside for a minute to hear Sarah.

It was the most generous off-handed “gift” that anyone ever gave me as I found myself utterly dumbfounded by being in the presence of Sarah Vaughan.

She was just sensational in every way. What she did with her voice in a pure, acoustic setting was spell-binding.

There’s a reason why all you have to say is “Sassy,” because to try to “say” anything else descriptively about Sarah’s music borders on the ineffable, especially when her music is “in performance” [I prefer that expression to “live”].

Needless to say, I caught her every chance I had while she was at Sugar Hill and took every opportunity thereafter to catch her “in performance.”

I thought the following remembrance of Sarah by bassist Andrew Simpkins would make a nice sequel to our recent posting about the recent release on Resonance Records of a CD capturing Sarah’s 1978 performance at Rosy’s Jazz Club in New Orleans, LA.

It appeared as a published interview conducted by Gene Lees in the November, 1997 edition of his Jazzletter.

“Richmond, Indiana, present population about 38,000, lies barely west of the Kentucky border and 68 miles due east of Indianapolis. Indianapolis was a hotbed of jazz, the birthplace of Freddie Hubbard, J.J. Johnson, the Montgomery Brothers, and a good many more, some of them known only regionally but excellent nonetheless. Wes Montgomery never wanted to leave Indianapolis, and ultimately went home.

Richmond is on a main east-west highway. It was Highway 40 in the days before the Eisenhower presidency, but now it is Interstate 70. No matter: as it passes through town, it is inevitably called Main Street. Richmond was early in its history heavily populated by anti-slavery Quakers, and continued its sentiments right into Copperhead days. Copperhead was the name applied to southern sympathizers in Indiana, formerly a Union state during the Civil War.

Andy Simpkins, one of the truly great bass players, whether or not he turns up in the various magazine polls, was born in Richmond on April 29, 1932. His father therefore was born within short memory distance of slavery itself. A black Chicago cop who was working on his degree in sociology taught me an important , principle: that a black man in any given job is likely to be more intelligent than a white man in the same job, for had he been white he would by now have risen higher in the system. This may not be a universal verity, but I have found the principle to be sufficiently consistent that I trust it. Andy's father illustrates the point. He was a janitor; that's what the society in his time would allow him to be. His private existence was another matter.

"My father did a lot of things in his life," Andy said. "In his younger years he played saxophone and clarinet a little bit. He worked for many years on the janitorial staff of the school system of Richmond. His real life — all through the years he worked for them — was growing plants. He grew vegetables and beautiful flowers and sold them to people in the area. He was a wonderful horticulturist. He had greenhouses, and his plants were famous.

"My father was an only child, I'm an only child, and I have one son, Mark, who is in radio in Denver, Colorado." Andy laughed. "The Simpkins family line runs thin!"

Andy combines formidable facility with a deep sound, beautiful chosen notes, long tones, and time that hits a deep groove. Those are some of the reasons he spent ten years with Sarah Vaughan.

In spite of occasional clashes, she adored him, and she did not suffer fools gladly or second-rate musicianship at all. Andy also worked for her arch-rival and close friend Carmen McRae, and mere survival with either of those ladies, let alone both of them, is perhaps the ultimate accolade for a jazz musician. They were prime bitches to work for. I merely wrote for Sass; I never had to work for her. I just loved her, and so did Andy. He remembers mostly the good times, and it was inevitable that we would talk about her.

Andy first came to prominence with a trio called the Three Sounds, whose pianist was Gene Harris. The drummer was Bill Dowdy. They made more than twenty albums for Blue Note. Andy toured for a long time with George Shearing, worked with Joe Williams, and recorded with Clare Fischer, Stephane Grappelli, Dave Mackay, and Monty Alexander.

He never forgets the role of his parents. For, as in the cases of most of the best musicians I have known, strong parental support and encouragement were critical elements in his development.

"My mother was a natural musician," Andy said. "She never had a lesson. She played piano by ear, and she had the most incredible ear. She played in our church for forty years, all the hymns and all the songs. She used to hear things. When my Mom would hear something playing on the radio she'd hum along, not the melody, like most people, but the inside harmony. I'd hear her humming those inside parts of the chords, any song she heard. It was incredible. I think that's where most of my musical talent comes from.

"But my Dad was really instrumental in seeing that I studied music and learned the theory, and to read, all the things you really need beside just your ear — although a lot of people have made it just on the ear. He saw I had a great ear and he started giving me lessons at an early age. And he made a lot of sacrifices to do that. To this day I think of my Dad making all kinds of sacrifices, doing extra jobs, picking up trash that he could sell for metal, just working so hard to make sure I had lessons, to see that I could study.

"Clarinet was my original instrument for a couple of years, and then I started studying piano. I had a great piano teacher, Norman Brown. Along with teaching me legitimate piano studies, and exercises, he also taught me about chord progressions and harmony. And that was very unusual at that time. Every week at my lesson, he would bring me a popular tune of the day, written out with the chords. So all the time I was studying with him, I was learning chords. And you know what else he did? He was a wonderful legitimate, classical player, but he also played for silent movies.

"I was fortunate: my mother and father lived long enough to see that I was successful. They were alive through the time I was with George Shearing. I was with George from '68 to '76. And before that the Three Sounds. We accompanied all sorts of people, and my Mom and Dad were in on that. Any time I was close enough that I could pick them up and take them, they would go to my gigs. Even when I was much younger, playing my jobs, my Mom sometimes would even nod out and go to sleep, but she would be there! She wanted to be there.

"I started out playing with a nice little local band in Richmond, a kind of combination of rhythm and blues and jazz. We used to play around Richmond and Muncie and a lot of little towns around there. When the band first started, we didn't have a bass player. I was playing piano. With the ear I had, I always heard bass lines, and I was playing the bass notes on the piano. A few months after we were together, a bass player joined us, from Muncie.

"I had listened to the bass before that. I had listened to the big bands. I was already hooked on jazz music. But I wasn't taken with the bass. There were all the great bass players working with those bands at that time. I guess it was the sound they got. It was the way bass was played at that time. They got kind of a short sound. The sound wasn't long and resonant.

"And this player joined the little band that we had. His name was Manuel Parker. He had this old Epiphone bass, it was American-made but it had a wonderful sound. He got this long, resonant sound that I'd never heard. I said, Wow! He could walk, and had that great groove, and this wonderful big fat resonant sound along with it. I was awestruck.

"We used to rehearse at my house a couple of times a week. I was probably eighteen, nineteen. He lived in Muncie, which was forty miles away from Richmond. Say we'd rehearse Tuesday and Thursday. So on Tuesday, he used to leave the bass at my house. I just started getting his bass out and playing with records. I knew the tunes. I'd tune the bass up, because the turntable ran a little fast. I heard all those lines. And I got hooked. No technique, I didn't know the fingering or any of that. But I heard the notes and I found them on the bass. And from that point on, that was it. I guess the other instruments were the route to the bass. This is where I was supposed to be, because it felt so totally natural.

"I was competent on the other instruments. I read well. In fact, when I went into the service I auditioned on clarinet and got into the band. I played them okay. People said I was a fairly good player. But I felt about the bass: this is the instrument that's been waiting for me.

"I was drafted into the Army in '53. Went through eight weeks of basic training at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri. I auditioned. The orders came down: I didn't make it. I had to take another eight weeks of basic. After the second eight weeks, I was accepted in the band. At that time, they had just started to desegregate the bands. But at the beginning, they were still segregated. After a few short months, I was transferred up to Indianapolis, to Fort Harrison — sixty miles from my home town! I played clarinet in the concert and marching band, bass in the big swing jazz band that we had within the band, and piano in a couple of small combos. That's when I really got around to studying.

"In the band there was a legit bass player, a wonderful classical player. He started to just teach me, on his own -legitimate, correct technique. I could read the bass clef, of course, from playing piano. He started teaching me correct classical fingering and approach to the instrument.

"I spent two years in the army, in the band the whole time, and fortunately was in Indianapolis. At the time, Indianapolis was swinging. It was live. J.J. Johnson might have left by then, but the Montgomery Brothers were there. I think Wes was still there. This was '53. I was going into town at night and hanging out, and not getting much sleep. I was playing at night with a lot of guys. [Drummer] Benny Barth was still there. I played a lot with Benny Barth. Al Plank was there. This town was rockin'. I went to one gig that went till midnight, and then I'd play an after-hours thing that went till three, then had to get up at six.

"And in the daytime, I played in the army band. I was submerged in music. I was really blessed. I didn't have to go and shoot at anybody and get shot. A lot of my friends in basic training went to Korea. Most of them didn't make it back. The 'police action', as they called it. I was in Indiana through 1955. I was discharged in '55.

"After the Army, I joined a little rhythm and blues band. The leader was from Chicago. His name was Jimmy Binkley. In the band that I played with back in Richmond, we had a sax player who called himself Lonnie 'The Sound' Walker. He was one of these rockin' tenor players. I sort of grew up around him. That's where we got the name for the Three Sounds. When we first formed, we were four: Gene Harris, Bill Dowdy on drums, myself, and Lonnie Walker. We called ourselves the Four Sounds. We went on from 1956 to '58. He left and we had a couple of different saxophone players. We went on as a trio and recorded our first record for Blue Note as the Three Sounds.

"The review in Down Beat ripped us asunder. It was by John Tynan. Here we are, our very first record, kids, fledglings, all optimistic excitement, and he tore us apart."

That review appeared in the April 16, 1959, issue of Down Beat, the second to have my name on the masthead as editor. Tynan — John A. Tynan to the readers, Jack or Jake Tynan to all of us who worked with him — presented the subject as the transcript of a court case in which a prosecutor says, "Here we have, beyond doubt, one of the worst jazz albums in years. The performances speak for themselves — horrible taste, trite arrangements, out-of-tune bass, an unbelievable cymbal, ideas so banal as to be almost funny."

The judge says, "Why was it ever released, then? Who would buy such a record as this?"

It must have been devastating to the members of that trio. Tynan became, and remains, one of my best friends. He left Down Beat to write news for the ABC television station in Los Angeles, a post at which he worked until his retirement. He lives now in Palm Desert, California. I called him, to see if he could lay his hands on that moldering review. He thought that he might, if he looked long enough. Nor could Andy readily provide a copy of it. So I undertook a little archaeology of my own and found it.

"In later years, on reflection," Andy said, "I thought there was some validity to what he said, but at that time he could have given us a little bit of a break. I guess that's not the way it is, if you're gonna be out there in the world. But at the time, we were really hurt. We went to see him. We were all over two hundred pounds, big strapping country boys. I guess we just looked at him real hard. I don't know what we had in mind."

Apparently nothing more violent than glowering. The Down Beat west coast office at that time was on Sunset Boulevard at Gower. Tynan remembers their visit only vaguely. Reconstructing the events, I found myself chuckling over the incident, all the more because just over four months later — in the September 3, 1959, issue of the magazine — the group received a glowing four-star review.

Andy said, "The three of us lived in Cleveland at first. Coming from a little town, I thought, Cleveland! I was really in the big town, after Richmond, Indiana. We went to Cleveland because Gene had an aunt there, and we could stay with her. There was an old club called the Tijuana, which I guess in the '40s was a big-time show club. It had been closed. It was just up the street from Gene's aunt's house. They were getting ready to reopen. They wanted fresh new talent. So we went and auditioned for the guy. They didn't even have a piano on the stage. The stage was surrounded by the bar, one of those deals. The piano was in the corner. The three of us got the piano and lifted it on the stage to do this audition. And we got the gig. We started out at $55 a week. We stayed two years and ended up getting $60. We got people coming in there.

"We met a guy who had a recording studio in his basement. He would record us when we rehearsed. Our idols at the time were Oscar Peterson, Ahmad Jamal, Max Roach, Horace Silver, Art Blakey, and all the people from that era. We had all their things down. We knew their charts!

"There was a jazz club downtown in Cleveland. We used to go there on Sundays, our night off, and hear all our idols. Gene was a very aggressive guy. He'd ask them if we could sit in. And they'd let us do it! We'd sit in with the horn players, and play their charts. It was very tolerant on their part. But we had those charts down.

"And by our doing that, the word began to filter back to New York about us.

"We had that gig at the Tijuana for a couple of years, and then finally it ended. Bill Dowdy says, 'My sister lives in Washington, D.C. Let's go to Washington. We can stay with her.' Bill and Gene are both from Benton Harbor, Michigan. They played together as kids long before I met either of them. They were in high school together. Bill's now in Battle Creek, Michigan. He's teaching there, privately and in one of the schools and he produces concerts. We're all still in touch. Gene lives in Boise, Idaho. I talk to Bill more than I do Gene.

"So we went to Washington. We got a lot of help from a guy who was a union representative. He took us around. He told us about one place that had been closed and was going to open again. It was called the Spotlight. We auditioned. The manager liked us, and we played there a month or so. Then we played in a restaurant in Washington for about nine months.

"A good friend of the manager of the place was Mercer Ellington. He came to listen and was just taken aback by us. Mercer was really the one who actually discovered us. A club in New York needed another group. Stuff Smith was playing there. They wanted a young group, new faces, to play opposite him. Mercer talked to them and they hired us.

"We'd been in Washington about a year when we went to New York. As I said, the word had filtered back from Cleveland about us — to Blue Note Records, Alfred Lion and Frank Wolff. They were wonderful people. They came to hear us at this club and loved us right away and signed us. At the same time, Jack Whittemore from the Shaw booking agency, little Jack, came in too. He was a wonderful man. Golly moses."

There was a radiance in his voice when Andy mentioned Jack Whittemore. One hears much, and much of it derisive, about the businessmen of jazz, particularly agents. But Jack was loved. He was kind, good, honorable, funny, feisty, tiny, stocky and argumentative. I used to call him the Mighty Atom. Once, in Brooklyn, he got into an argument and then a fist-fight with the owner of a jazz club, over the issue of the acts Jack had been booking in there. The bartender separated them and told them to cool off. Jack asked the owner if business was really that bad. He said it was. "Then why don't you come to work for me?" Jack said, and that's how Charlie Graziano became Jack's second in command and one of his best friends. Jack was like that.

Jack had been an agent for GAC and MCA before becoming president of the Shaw agency, which in the 1960s was the primary jazz booking agency; later he went on his own, and the acts he booked included Miles Davis, Bill Evans, Art Blakey and the Jazz

Messengers, Sonny Stitt, Stan Getz, McCoy Tyner, Phil Woods, Horace Silver, and many more. When Jack died at sixty-eight in 1982, the professional jazz community was devastated. There was no one to replace him, and no one has turned up since to fill his shoes. After his death, all the musicians he booked paid Jack's estate the commissions they owed him, with a single exception — and everyone in the business knew it — Stan Getz.

This precis of Jack's career will explain the warmth in Andy's voice on mention of his name. Jack could make a career; Horace Silver credits Jack with establishing his.

"Jack came to hear us," Andy said. "He liked us, and he signed us with Shaw. From that point, we started to record for Blue Note. We did quite a few albums for Blue Note.

"And a funny thing happened. The Down Beat review was so scathing that I think it made people curious. They started buying our albums and got us off the ground. I really believe that. How could anything be that bad? People said, I've gotta hear this! I believe that to this day.

"We started recording in '58. I stayed with the Three Sounds until '66. At that point, we'd made twenty albums or so together. In the meantime, we did some records for other companies — Limelight, which was a subsidiary of Mercury. Jack Tracy was our producer. I saw Jack recently! We did one with Nat Adderley for Orrin Keepnews at Riverside. It was a wonderful record, called Branching Out. We recorded some for Verve, too."

"That was one hell of a trio," said bassist John Heard. Born in 1938, John was twenty when that trio began to record; Andy was by then twenty-six, and that much difference in age is a lot at that time in one's life. "When they'd come to play Pittsburgh," John said, "I used to stand around outside the club and listen to them. I used to follow Andy around. He didn't know. I don't think he knows it now. Andy is a Monster."

"Bill Dowdy left the Three Sounds before I did," Andy said. "Bill was good at business matters. He was very orderly. He used to take care of books and that kind of thing for us. He and Gene had a big falling out. And they'd been friends since school days. Bill left in '65. I left about a year later, only because I wanted to play some other music with other people. I wanted to branch out musically. I came to Los Angeles. There were all these great players, and I wanted to work with them and expand musically. For a couple of years I was in L.A. freelancing.

"Somebody told George Shearing about me and he needed a bass player. I went to his house and auditioned for him, just the two of us. He pulled out a couple of charts and I read them. He said, 'I always had heard that you didn't read. I don't know where this came from, but you read fine.'"

"Well you know, Andy," I said, "that may seem like a small detail now, this is the kind of rumor that can seriously impede someone's career. I'd always heard that Chet Baker couldn't read, and Gerry Mulligan told me that was nonsense. He said Chet could read, but his ear was so good he didn't have to. He could learn anything instantly."

"I know, I know," Andy said. "Well I read for George, and joined him in 1968. I replaced Bob Whitlock. Charlie Shoemake was the vibes player, Dave Koontz was the guitarist, Bill Goodwin was the drummer. Bill left soon after. There were different guys through the years. Stix Hooper played with us for about a year. Harvey Mason played drums with us, Vernel Fournier for just about a minute. I was with George for eight years.

"I knew a lot of songs, but I credit George: I learned a lot of songs from George Shearing, kind of remote things. I'll tell you another song I credit for teaching me a lot of songs, remote songs, and that's Jimmy Rowles. Rowles! Listen! Those two guys, along with my piano teacher, are responsible for a lot of things that I know.

"I left George in '76. I was still living in L.A. Back to freelancing and studio calls and gigs and casuals. I was married to my first wife, Katherine, in 1960. She passed away in '92. She had lung cancer. She smoked, she smoked. My wife Sandy quit smoking a couple of years ago.

"After Shearing I was doing film calls and studios and this and that. Then I got a call in '79 from Sarah Vaughan's then husband, Waymon Reed. Trumpet player. He was her music director. Sarah was looking for a bass player, and I'd been recommended. I auditioned for Sarah, and she loved me. I spent ten years with her. Until 1989.

"It was a great relationship. She could be weird," he said, laughing. "As everyone who worked for her knows. Especially players."

"Well my relationship with her was a little different," I said. "I dealt with her as a songwriter. And as an old friend."

I recounted to Andy the details of an event in which our trails almost crossed. I had written an album for Sarah, based on poems of peace by the present Pope. The producer was the well-known Italian entrepreneur Gigi Campi, who among other achievements had founded and funded and managed the remarkable Clarke-Boland Big Band, jointly led by drummer Kenny Clarke and the Belgian arranger and composer Francy Boland. Sass wanted to use her own rhythm section, but Gigi Campi insisted on organizing his own for the project, which involved a large orchestra, recorded in Germany. He hired two bassists, Jimmy Woode and Chris Lawrence, and the drummer was Edmund Thigpen. Nothing wrong with that rhythm section, but facing some difficult musical material, Sass no doubt would have felt more secure with her own, which included, besides Andy, the pianist George Gaffney, whose background includes periods as music director for Peggy Lee and Ben Vereen, among others.

"The Sass lady!" Andy said. "That album you wrote for her, it was aside from the kind of thing she usually did. And how well, how unbelievably, she learned and did it. Difficult music. Good heavens. That was '84? Did you see her being more disagreeable than usual?"

"Not particularly." I said. "She was too scared of that material, and I was the only one who could teach it to her. She could be crusty, though. She pulled it on other people there, but not on me. Although, I'll tell you, she could be demanding, even of me."

I told him the story. After she had sung the material in a triumphant concert in Dusseldorf, and it had been recorded, I flew home to California. But Sass, hearing the tapes, was unhappy with some of the tracks and wanted to overdub the vocals. This was to be done in a studio in Cologne. And she insisted that I return to Germany to be with her. So, after two or three days at home, I flew back to Germany, and held her hand in the studio — and since she was listening to the orchestra in headphones and I couldn't hear it, I heard that incredible voice of hers totally unadorned.

"Well after that," Andy said, "we did an Italian tour. She wanted to have an audience with the Pope."

"That started when we were in Germany," I said. "Everywhere she and I went the press asked us if we had met the Pope. And eventually she got a bee in her bonnet that she wanted to meet him. Curiously enough, I met him — met? a handshake — in Columbia, South Carolina, during his American visit. There was a huge rally and I sang some of that material in the concert. But she wanted to meet him even by the time we finished recording."

"Well she did," Andy said. "The promoter we were with in Italy got her an audience with the Pope. That's no small matter. This guy was a heavyweight, named Corriaggi.""Who was her pianist during that period?" I asked. "There were a lot of people, but for the longest period it was George Gaffney. He's wonderful. A great arranger too.

"As great as she was, she sometimes had trouble relating to real life. She had some strange ideas about normal, everyday living. She seemed to attract wrong guys. There were guys out there going for who she was and what she had and the prestige of being involved with her."

"I met some of those guys," I said. "I believe that she was very insecure."

"Oh sure," Andy said. "I had a couple of run-ins with her, as anyone would who was with her for a long period. About the silliest things. For instance, we were traveling. I was using a flight case for the bass. She bought one; I was using that. They're always big, and they weigh a lot, but they have to be to protect the instrument. And sometimes they don't even work. That amazes me. On a couple of instances, I've opened it up after a flight and the bass was in shambles inside the trunk.

"So I decided to have one custom-made. When I did that, she turned left. Suddenly she didn't want to pay the oversize charges when you fly. They'd been paying it right along. It's not my expense. The promoter pays for it. It's like the tickets. She went really out on me about that! And the one I'd had made was lighter than hers.

"But the things that really made me mad — and she made everyone mad who worked for her, and they loved her at the same time - - seemed to melt away when she opened her mouth. Sometimes you'd want to stomp her into the ground. And then she'd start singing, and none of it mattered. I've talked to I don't know how many guys about this.

"After about "five or six years with her, and the damage to the instrument, even in the trunk, I got gun-shy about it. I started — and this is tricky to do with a stringed instrument — to have them write it into the contract that the producer had to provide a bass. Sometimes you win, and a lot of times you lose. A lot.

"The best way to find a decent instrument in an area is to get in touch with a symphony player or a jazz player, or somebody who does both, who might want to rent one of his instruments. The chances were better that way that you could find something good. Otherwise you'd have to go to a store.

"With all that mind, I came out better than I would have thought, most of the time.

"But one time I had an instrument that was the worst I ever had. It would not stay in tune. You'd play a few notes, and it would start slipping and go flat. We had this one tune we did together, just she and I, East of the Sun. Just bass and voice. It was in five flats. We're doing it and this bass is slipping, it was going all over the place. And she went where it went! I'm going nuts. And she just heard it, and found wherever it was. At the end of the tune, the piano always played a Count Basie ending. Plank, plank, plank. George Gaffney was with us at the time. Of course, it was 'way somewhere else from where we were.

"But her ears! It was the darnedest thing I ever heard in my life, man. She was right with me. We were together, but we weren't in the key. I'd heard her do amazing things up till then, but I said, 'Lord, have mercy, what is this! She constantly amazed me, but that incident took the cake."

I said, "Sahib Shihab told me once that Big Nick Nicholas said you should listen to her if only for the way she used vibrato. And she had a weird ability to hit a note in tune and then seem to penetrate even more into the heart of the pitch. It was the strangest thing."

"Yeah!" Andy said. "It was, Wow! If I can play a ballad at all, interpret a ballad, I would have to credit that to her. I'd play one sometimes on a set, and I told her that, and she loved it. I recorded My Foolish Heart on one of my albums.

"When I was working with Gerald Wiggins — I worked with him quite a lot — he heard it. We worked at a place called Maple Drive in Beverly Hills, and a place called Linda's — and he would insist that I play it every night. I'd say, 'Oh Wig, I don't want to.' He'd say, 'Shut up and play it.' I was still with Sarah at the time.

"I got it on record, and I wanted her to hear it. As I said, I'd learned how to approach a ballad melodically from her. Just through osmosis. I played the record for her. I was nervous. And she said, 'Andy, that is gorgeous.'

"That was not long before she passed.

"After she got sick, during that last year, we did a tour. This would be around '88, to Italy. This promoter, Corriaggi, who was Frank Sinatra's promoter over there, booked us, and the tour was great. I knew her moods. She was totally evil that whole tour, and it was the best tour we ever did. The weight that this guy carried! We didn't even go through customs. It was a car tour, surface. There were two cars, Rolls-Royces, a car for her and a car for us. He used to take us to these great places to eat. They'd be closed, but they'd stay open especially for us. The greatest food, the best treatment. Whatever she wanted, and the same with the band. And she was totally evil all the time. I know she could be weird, but this was . . . But now I think back and I believe she was getting ill, even then. Her breath was getting shorter. We'd be walking through an airport, and she'd have to stop, panting, and rest. So I think it was coming on her at that time, and we didn't know what it was.

"She could be totally exasperating. Looking back, however, I have to think very hard about the things that made me angry with her. I seem to remember all the fun things and the laughs and the great times. Which says to me that those other things weren't that important.

"She was really hurt when I left. But, again, I just wanted to move further on and do other things. But she didn't travel that long after that anyway. We used to do a thing where we'd end up on two notes, in harmony. She'd jump on me and say, 'I want to sing that note, the bass note."

I mentioned the times when it was said that she had a four-octave range and she would huff, "The day I've got four octaves, I'm calling the newspapers."

Andy laughed. "She always used to deny that, but I think she did. She certainly had three. That's a definite.

"Those were incredible years. I was ten years with her. I left in '89. She died a year or so later. Sarah really spoiled me for singers. I had to pull myself together and say, 'This is not right. There are other people who can sing, you know.' I found myself unconsciously comparing.

"When it comes to scatting, Ella did it well. Sarah did it well. Carmen did it well. But in my estimation, the queen of scatting is Betty Carter. She does it as an instrumentalist does. Most people need to not scat, I'm gonna tell you."

"I don't like scat singing most of the time," I said.

"I don't either," Andy said.

"If any singer was ever qualified to do it, it was my hero, Nat Cole. And he didn't do it. He just sang the song. The best scatting I've heard comes not from singers but from instrumentalists, Dizzy, Clark Terry, Frank Rosolino."

"And don't forget the trombone player, Richard Boone!" Andy said. "But I really feel most people need to leave it alone. What I like about Betty is the sounds don't vary. She oo's and ah's for different notes and registers."

I said, "The schools are teaching scat to young singers, and I wish they wouldn't."

"Yeah," Andy said. "How about knowing a song as written? At least before you start scatting. Some people don't even know the song. Please! There are a lot of singers that I like, and I used to run them by Sass. Julius La Rosa, for one. I said, 'I think he's great.' She said, ‘Yeah!' People who can really sing. First of all, I can understand the lyrics, and that takes me a long way. And they can sing in tune. And in time. I always thought Julius La Rosa was wonderful. And I think Steve Lawrence sings great too. I always liked Gloria Lynn.

"I'd like to ask you a little about the bass, and about your own playing. Your said you didn't really like some of the old style of bass players."

"The notes were on the money," Andy said. "But the sound wasn't there."

"They used to use full-hand grips instead of fingering the instrument."

"And that's why the sound wasn't happening," Andy said. "You're using the balls of your fingers to mash the strings all the way down to the fingerboard."

"Don Thompson and I were talking a year or two ago about individual tone on an instrument. And he said he thought it was almost impossible not to have a personal individual tone, for physical reasons."

"Certainly," Andy said. "Don's right. That's the thing about stringed instruments. The pressure. What part of your finger you're playing on when you press the strings down. And so far as pizzicato is concerned, the part of your picking finger that you play with. The tip, or the longer part of the finger? These things are crucial. They make the difference. That's why I feel as I do about the instrument. You can take five bass players and have them play the same bass, and they'll sound different."

I told him that once I had watched Ray Brown instructing a student. Ray took the boy's instrument, a cheap Kay student-model bass. And he produced from it the same sound he did from his own instrument. I asked, "Where do you think the business of long sustained tones began?"

"In my memory, Blanton got that," Andy said. "This guy! And I guess all the guys at that time played without amplification. He stands out as far as being big in his sound, playing with a full band, with no help but just his strength."

I said, "Then came Mingus, Ray Brown, Red Mitchell, Scott LaFaro. No instrument evolved as much as the bass after about 1945."

"That's probably true. Red Mitchell is a definite influence in my playing. Of course, he did that cello tuning, fifth tuning. The range is wider. I've got a lot of younger heroes, like Stanley Clarke. Age doesn't matter. A real large hero of mine is Niels Pedersen. Oh, I mean! He seems to cover the whole spectrum of great sound, a strong walking time sound, great facility. A lot of cats have facility, but he plays and phrases like a horn or pianist would, and has the facility to back it up, and harmonically he's always on the money. And tempos don't matter."

"How is that long sound produced?"

"It has to do with a lot of things. Part of it is the instrument itself. But those earlier guys had good instruments too. Foreign instruments, which so many of the great ones are. Mine's German. It's about 150 years old. It's a kid compared to some that I know about. German, French, Italian. Those old craftsmen.

"It has to do also with the way the instrument is set up, as far as the way the sound post inside of the instrument is set. It has to do with the height of the bridge. A higher bridge produces a bigger sound, but it's more difficult to play. Mine is not high, but it's not super-low. Some guys have the strings down so close to the fingerboard that you've got to really play light or you'll start getting slapping."

"Of course," I said, "the amplification has been so improved."

"Yes, we do have that. But I still like to have gigs turn up now and then where you can play acoustic. They're getting rare any more. I've been playing Fridays and Saturdays at a hotel in Santa Monica called Shutters, with an outstanding pianist named John Hammond. He worked for Carmen."

"That says it."

"We played together with Carmen at the old Donte's. He's a marvelous players. I keep the amp really low, just a touch."

And that brought us back, inevitably, to Sarah. "The Sarah stories go on and on," Andy said with a quiet and affectionate chuckle. So I told him another one.

Some years ago, Roger Kellaway wrote and produced an album — an outstanding album, but little noticed — for Carmen McRae. I had heard the tapes, the rough mixes. And one day I was over at Sarah's house. She lived in Hidden Hills, a gated community just off the 101 freeway a little west of Woodland Hills, California. She had just done some of my songs. I said to her, "You've been recording a number of my songs. Thank you."

"Hmm," she said with a certain sniffy hauter, "I thought you'd never mention it."

She made us drinks, and after a while she said, "How's that album Carmen did with Roger?"

"Very nice," I said. "Beautiful charts, beautiful recording."

She had just risen to her feet to refill our glasses. "No," she said, "I mean, how's Carmen singing on it?"

"Sharp," I said.

She continued across her sunny living room toward the bar, monarchical in manner, though she was not very tall, her words trailing loftily over her shoulder: "Shit. I didn't know anybody but me knew that Carmen sings sharp."

Andy roared with laughter.

"Oh that Sass," he said wonderingly. And warmly.”

In addition to working with Shorty’s small group primarily in 1953, Paich took a series of jobs in the Los Angeles music and recording industry. These included arranging (and playing) the score for the Disney Studio's full length cartoon film The Lady and The Tramp, working as accompanist for vocalist Peggy Lee [who was also heavily involved in developing the music for the Disney animation], touring with Dorothy Dandridge, and providing arrangements for many local bands in Los Angeles.

In addition to working with Shorty’s small group primarily in 1953, Paich took a series of jobs in the Los Angeles music and recording industry. These included arranging (and playing) the score for the Disney Studio's full length cartoon film The Lady and The Tramp, working as accompanist for vocalist Peggy Lee [who was also heavily involved in developing the music for the Disney animation], touring with Dorothy Dandridge, and providing arrangements for many local bands in Los Angeles.  Employing Bob Enevoldsen on everything from valve trombone to vibes to tenor saxophone, Harry Klee on bass as well as alto flute using the piano’s upper register to play unison lines in the upper horn or trumpet register, Paich develops orchestral colors that are reminiscent of everything from the Woody Herman four brothers sound [from which, no doubt, the name – “Tenors West” – is derived] to the yet-to-come Henry Mancini hip, slick and cool Peter Gunn resonances. A trumpet plays under a baritone sax, a bass plays “lead” in a “choir” made up of trumpet, flute and piano, and rhythmic riffs and motifs punctuate backgrounds everywhere. On this recording, Marty is the musical equivalent of a kid in a toy store trying everything in every combination.

Employing Bob Enevoldsen on everything from valve trombone to vibes to tenor saxophone, Harry Klee on bass as well as alto flute using the piano’s upper register to play unison lines in the upper horn or trumpet register, Paich develops orchestral colors that are reminiscent of everything from the Woody Herman four brothers sound [from which, no doubt, the name – “Tenors West” – is derived] to the yet-to-come Henry Mancini hip, slick and cool Peter Gunn resonances. A trumpet plays under a baritone sax, a bass plays “lead” in a “choir” made up of trumpet, flute and piano, and rhythmic riffs and motifs punctuate backgrounds everywhere. On this recording, Marty is the musical equivalent of a kid in a toy store trying everything in every combination.  Charles Barber described Marty’s skills as a composer arranger as follows:

Charles Barber described Marty’s skills as a composer arranger as follows:  On Bass Hit, Paich surrounds Brown with his “small” big band, a format, as has been noted, that Paich was becoming quite expert at. This one included such distinctive soloists as trumpeter Harry “Sweets” Edison, Herb Geller on alto sax, clarinetist Jimmy Giuffre with his signature lower and mid range sound, guitarist Herb Ellis along with pianist Jimmy Rowles and the always-present-on-Marty-Paich-led-dates, Mel Lewis on drums, to round-out the rhythm section. Ray Brown and the stellar players joining him on this recording all benefited from Marty’s “gift” of writing arrangements that allowed them to put their personality into the music.

On Bass Hit, Paich surrounds Brown with his “small” big band, a format, as has been noted, that Paich was becoming quite expert at. This one included such distinctive soloists as trumpeter Harry “Sweets” Edison, Herb Geller on alto sax, clarinetist Jimmy Giuffre with his signature lower and mid range sound, guitarist Herb Ellis along with pianist Jimmy Rowles and the always-present-on-Marty-Paich-led-dates, Mel Lewis on drums, to round-out the rhythm section. Ray Brown and the stellar players joining him on this recording all benefited from Marty’s “gift” of writing arrangements that allowed them to put their personality into the music.  In 1957, Marty contributed two charts to the Kenton book that were recorded in January of the following year for Stan’s Back to Balboa album [Capitol Jazz 7243 5 93094 2]. These were the furiously up-tempo The Big Chase and an absolutely stunning arrangement of My Old Flame. Michael Sparke, the noted expert on all-things-Kenton when its comes to his studio recordings had this to say about Marty’s association with Stan and these arrangements:

In 1957, Marty contributed two charts to the Kenton book that were recorded in January of the following year for Stan’s Back to Balboa album [Capitol Jazz 7243 5 93094 2]. These were the furiously up-tempo The Big Chase and an absolutely stunning arrangement of My Old Flame. Michael Sparke, the noted expert on all-things-Kenton when its comes to his studio recordings had this to say about Marty’s association with Stan and these arrangements:  The occasion would be a four day-celebration involving alumni members of the Kenton band organized by Ken Poston, then of jazz radio station FM88.1 KLON, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Kenton Orchestra’s debut at the Rendezvous Ballroom on Balboa Island, CA.

The occasion would be a four day-celebration involving alumni members of the Kenton band organized by Ken Poston, then of jazz radio station FM88.1 KLON, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Kenton Orchestra’s debut at the Rendezvous Ballroom on Balboa Island, CA.  Also in 1957, Marty continued his band-within-band love affair with the release of nine of his original compositions on the Cadence Records Marty Paich Big Band [CLP-3010] which was issued on CD as Marty Paich: The Picasso of Big Band Jazz [Candid CCD 79031].

Also in 1957, Marty continued his band-within-band love affair with the release of nine of his original compositions on the Cadence Records Marty Paich Big Band [CLP-3010] which was issued on CD as Marty Paich: The Picasso of Big Band Jazz [Candid CCD 79031].

In his liner notes for the album, Lawrence D. Stewart observed that:

In his liner notes for the album, Lawrence D. Stewart observed that:  In 1959, the year before the Shubert Alley recording, vibraphonist Terry Gibbs began fronting a big band on Monday nights [the customary off night for working musicians] at a few venues in Hollywood. Later to be called the “Dream Band,” during its initial existence is was sometimes referred to as “The Bill Holman Band” because most of the bands early charts were “loaned” by Bill as Terry could barely afford to pay the musicians, let alone, buy arrangements.

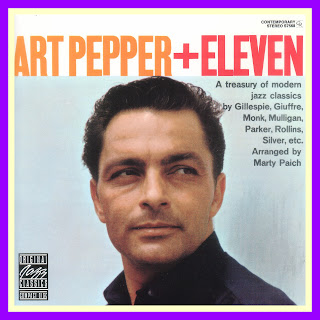

In 1959, the year before the Shubert Alley recording, vibraphonist Terry Gibbs began fronting a big band on Monday nights [the customary off night for working musicians] at a few venues in Hollywood. Later to be called the “Dream Band,” during its initial existence is was sometimes referred to as “The Bill Holman Band” because most of the bands early charts were “loaned” by Bill as Terry could barely afford to pay the musicians, let alone, buy arrangements.  On Art Pepper + Eleven: A Treasury of Modern Jazz Classics [Contemporary OJCCD 341-2] the Pepper- Paich mutual admiration society produced a Jazz classic with a recording that is an almost perfect representation of the skills of everyone involved: from Les Koenig, owner of Contemporary whose idea it was to put the pair together in such a setting, to Pepper’s outstanding soloing on alto sax, tenor sax and clarinet [not to mention Jack Sheldon’s as the “other voice” on trumpet]; to Marty’s scintillating and inspiring arrangements; to all of the musicians on the date in executing his charts both with accuracy, style and for infusing them with a sense of excitement.

On Art Pepper + Eleven: A Treasury of Modern Jazz Classics [Contemporary OJCCD 341-2] the Pepper- Paich mutual admiration society produced a Jazz classic with a recording that is an almost perfect representation of the skills of everyone involved: from Les Koenig, owner of Contemporary whose idea it was to put the pair together in such a setting, to Pepper’s outstanding soloing on alto sax, tenor sax and clarinet [not to mention Jack Sheldon’s as the “other voice” on trumpet]; to Marty’s scintillating and inspiring arrangements; to all of the musicians on the date in executing his charts both with accuracy, style and for infusing them with a sense of excitement.  And finally, after contributing full big band arrangements for others during 1959, Marty was given the opportunity to write them for his own big band when Warner Brothers records approached him to make an album which was eventually combined with an earlier 1957 recording on Cadence and issued and re-issued under a variety of titles [Moanin', The Broadway Bit, I Get A Boot ouf of You].

And finally, after contributing full big band arrangements for others during 1959, Marty was given the opportunity to write them for his own big band when Warner Brothers records approached him to make an album which was eventually combined with an earlier 1957 recording on Cadence and issued and re-issued under a variety of titles [Moanin', The Broadway Bit, I Get A Boot ouf of You].  In 1959, there was also the continuing alliance with Art Pepper, although as Ted Gioia makes clear:

In 1959, there was also the continuing alliance with Art Pepper, although as Ted Gioia makes clear: