© -Steven Cerra. Copyright protected; all rights reserved.

Have you ever wondered why a Jazz big band works the way it does, let alone, how it works at all?

Why the instrumentation is the way it is - generally 4 trumpets, 3-4 trombones, 5 saxes and a rhythm section made up of piano, bass and drums with a guitar added to it on occasion?

How the music they play is organized, arranged and constructed?

The very best explanation I have found to the question of how and why a Jazz big band works the way it does - especially one that includes a historical perspective on how the craft [or art, if you prefer] evolved - is contained in the following essay by the late, esteemed Jazz author, Gene Lees.

Pencil Pushers

JazzLetter

November 1998

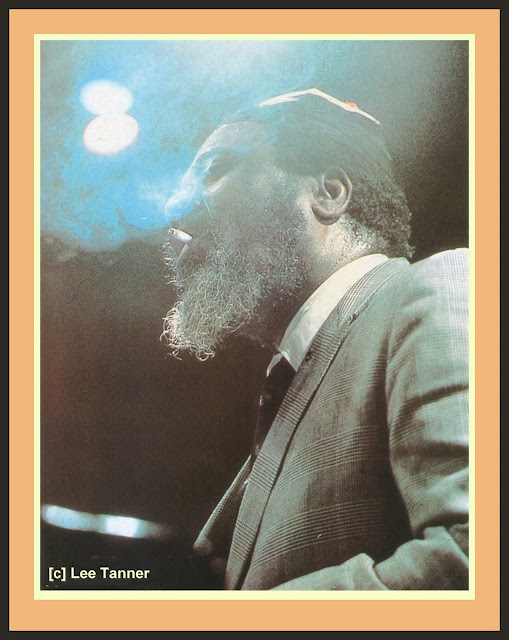

“One sunny summer evening when I was about thirteen, I saw crowds of people pouring into the hockey arena in Niagara Falls, Ontario. Curious to know what was attracting them, I parked my bicycle behind the arena (in those days one had little fear that one's bicycle would be stolen) and, in the manner of boys of that age, I sneaked in a back exit. What was going on was a big band. I remember watching as dark-skinned musicians in tuxedos assembled on the stage, holding bright shining brass instruments, taking their seats behind music stands. And then a man sat down at the piano and played something and this assemblage hit me with a wall of sound I can still hear in my head, not to mention my heart. I now can even tell you the name of the piece: it was Take the "A " Train, that it was written by one Billy Strayhorn, that the band was that of Duke Ellington, and that the year had to be 1941, for that is the copyright date of that piece.

I learned that bands like this came to the arena every Saturday night in the summer, and I went back the following Saturday and heard another of them.

I was overwhelmed by the experience, shaken to my shoes. It was not just the soloists, although I remember the clowning and prancing and trumpet playing of someone I realized, in much later retrospect, was Ray Nance with Ellington, and a tenor saxophone player who leaned over backwards almost to the stage floor, and that had to have been Joe Thomas with Jimmie Lunceford. With both bands, it was the totality of the sound that captivated me, that radiant wall of brass and saxes and what I would learn to call the rhythm section.

I discussed the experience with my Uncle Harry. When I told him about these bands I'd seen, he encouraged my interest and told me I should pay attention as well to someone called Count Basie.

My Uncle Harry — Henry Charles Flatman, born in London, England — was a trombone player and an arranger He played in Canadian dance-bands in the 1920s and '30s, and I would hear their "remote" broadcasts on the radio. Once one of the bandleaders dedicated a song to me on the air. I am told that I could identify any instrument in the orchestra by its sound by the time I was three, but that may be merely romantic family lore.

But what held these instruments together in ensemble passages? I even knew that: people like my Uncle Harry. I remember him sitting at an upright oaken piano with some sort of big board, like a drawing board, propped above the keyboard. He always had a cigarette dangling from his mouth, and one eye would squint to protect itself from the rising tendrils of smoke, while his pencil made small marks on a big paper mounted on that board: score paper, I realized within a few years. He was, I'm sure he explained to me, writing "arrangements" for the band he played in. I seem to recall that he was the first person to tell me the difference between a major and minor chord.

Because of him I was always aware that the musicians in a band weren't just making it up, except in the solos. Somebody wrote the passages they played together.

And so from my the earliest days I looked on the record labels for the parenthesized names under the song titles to see who wrote a given piece. When the title wasn't that of some popular song and the record was an instrumental, then chances were that the name was that of the man who composed and arranged it. Whether I learned their names from the record labels or from Metronome or Down Beat, I followed with keen interest the work of the arrangers. I became aware of Eddie Durham, whose name was on Glenn Miller's Sliphorn Jive which I just loved (he was actually a Basie arranger); Paul Weston and Axel Stordahl who wrote for Tommy Dorsey; Jerry Gray, who wrote A String of Pearls, and Bill Finegan, who arranged Little Brown Jug, both for Glenn Miller; and above all Fletcher Henderson, who wrote much of the book (as I would later learn to call it) of the Benny Goodman band. Later, I became aware of Mel Powell's contributions to the Goodman library, such as Mission to Moscow and The Earl, as well as those of Eddie Sauter, including Benny Rides Again and Clarinet a la King, Jimmy Mundy's contributions to that band included Swing-time in the Rockies and Solo Flight, which introduced many listeners to the brilliance of guitarist Charlie Christian; and Gene Gifford, who wrote Smoke Rings and Casa Loma Stomp for the Casa Loma Orchestra led by Glen Gray.

The better bandleaders always gave credit to their arrangers, whether of "originals" or standards such as I've Got My Love to Keep Me Warm, and I became aware of Skip Martin (who wrote that chart), Ben Homer and Frank Comstock with Les Brown, and Ralph Burns, Shorty Rogers, and Neal Hefti with Woody,Herman, Ray Conniff with the postwar Artie Shaw band ('Swonderful and Jumpin' on the Merry Go Round are his charts) and, later, Bill Holman with various bands, and then Thad Jones and Gerald Wilson. Some of the arrangers became bandleaders themselves, including Russ Morgan (whose commercial band gave no hint that he had been an important jazz arranger), Larry Clinton, and Les Brown. And of course, there was Duke Ellington, though he was not an arranger who became a bandleader but a bandleader who evolved into an arranger— and one of the most important composers in jazz, some would say the most important.

I daresay the arranger I most admired was Sy Oliver. It was many years later that I met him. He wrote the arrangements for an LP Charles Aznavour recorded in English. I wrote most of the English translations and adaptations for that session, and about all I can remember about the date is the awe I felt in shaking the hand of Sy Oliver.

I was captivated by the Tommy Dorsey band of that period. From about 1939 on, I thought it was the hottest band around. I did not then know that Sy Oliver was the reason.

He was born Melvin James Oliver in Battle Creek, Michigan, on December 17, 1910. He began as a trumpet player and, like so many arrangers, trained himself, probably by copying down what he heard on records. In 1933, he joined the Jimmie Lunceford band, playing trumpet and writing for it, and it is unquestionable that some of the arrangements I was listening to that night in Niagara Falls were his. Others were surely by Gerald Wilson.

A few years after his death, Sy's widow, Lillian, told me that Lunceford paid Sy poorly and Sy was about to leave the music business, return to school and become a lawyer. He got a call to have a meeting with Tommy Dorsey. Dorsey told him he would pay him $5,000 a year more (a considerable sum in the 1940s) than whatever Lunceford was giving him, pay him well for each individual arrangement as opposed to the $2.50 per chart (including copying) he got from Lunceford, and give him full writing credits and attendant royalties for his work if Sy would join his band. Furthermore, he told Sy that if he would give him a year, he, Tommy, would rebuild the band in whatever way Sy wanted.

Sy took the offer, and Tommy rebuilt the band that had in the past been known for Marie and Song of India and the like. It became the band of Don Lodice, Freddy Stulce, Chuck Peterson, Ziggy Elman, Joe Bushkin, and above all Buddy Rich, who gave it the drive Sy wanted and whom Sy loved. The change was as radical as that in the Woody Herman band from the Band that Plays the Blues to the First Herd of Caldonia and Your Fathers Mustache. It became a sort of projection of Sy Oliver led by Tommy Dorsey, and Sy's compositions and charts included Well, Git It!, Yes Indeed, Deep River, and, later on (1944) Opus No. 1, on which Lillian Oliver received royalties until the day she died, and their son Jeff does now.

Recently I mentioned to Frank Comstock my admiration for Sy Oliver, and he said, "I think Sy touched all of us who were arranging in the 1940s and '50s and later." And then he told me something significant.

Frank said that he learned arranging by transcribing Jimmie Lunceford records, which doubtless meant many Sy Oliver charts. Frank's first important professional job was with Sonny Dunham. "And he was known, as I'm sure you're aware, as the white Lunceford," Frank said. The reason, Frank said, was that when Dunham was starting up his band, Lunceford gave him a whole book of his own charts to help him get off the ground. And Frank was hired precisely because he could write in that Lunceford-Oliver manner.

In the various attempts to define jazz, emphasis is usually put on improvisation. Bill Evans once went so far as to say to me that if he heard an Eskimo improvising within his musical system, assuming there was one, he would define that as jazz. It is an answer that will not do.

There are many kinds of music that are based on, or at least rely heavily on, improvisation, including American bluegrass, Spanish flamenco, Greek dance music, Polish polkas, Gypsy string ensembles, Paraguayan harp bands, and Russian balalaika music. They are not jazz. In the early days of the concerto form, the soloist was expected to improvise his cadenzas; and well-trained church organists were expected, indeed required, to be skilled improvisers, up to and including large forms. Gabriel Faure was organist at La Madeleine. Chopin and Liszt were master improvisers, and the former's impromptus are what the name implies: improvisations that he later set down on paper, there being no tape recorders then. Doubtless he revised them, but equally doubtless they originated in spontaneous inventions. Beethoven was a magnificent improviser, not to mention Bach and Mozart.

Those who like to go into awed rapture at the single-line improvisation of a Stan Getz might well consider the curious career of Alexander Borodin. First of all he was one of the leading Russian scientists of his time, a practicing surgeon and chemist, a professor at the St. Petersburg Medico-Surgical Academy. (He took his doctorate on his thesis on the analogy of arsenic acid with phosphoric acid.) Music was never more than a relaxing hobby for him, and his double career raises some interesting questions about our modern theories on left-brain logical thought and right-brain imaging and spatial information processing. Borodin improvised his symphonies before writing them down. And if that seems impressive musicianship, consider Glazunov's. Borodin never wrote his Third Symphony down at all: he improvised the first two movements and fyis friend Glazunov wrote out the first two movements from memory in the summer of 1887, a few months after Borodin's death. (He constructed a third movement out of materials left over from other Borodin works, including the opera Prince Igor.)

Most of the Borodin Third Symphony, then, is improvised music. I can't imagine that anyone, even Bill Evans (if he were here), would try to call it jazz.

How then are we to define jazz?

The remark "if you have to ask, you ain't never gonna know," attributed to both Louis Armstrong and Fats Waller, is clearly unsatisfactory, though a certain kind of jazz lover likes to quote it for reasons that remain obscure. You could say that about many kinds of music. It is an evasion of the difficulty of definition.

A simple definition won't cover all the contingencies, and a complex one will prove ponderous and even meaningless. Even if you offer one of those clumsy (and not fully accurate) definitions such as "an American musical form emphasizing improvisation and a characteristic swing and based on African rhythmic and European harmonic and melodic influences," you have come up with something that conveys nothing to a person who has never heard it. Furthermore, the emphasis on improvisation has always been disproportionate. Many outstanding jazz musicians, including Art Tatum and Louis Armstrong, played solos they had worked out and played the same way night after night. Nat Cole's piano in the heads of such hits as Embraceable You were carefully worked out and played the same way repeatedly. Bandleaders of the era would tell you their players had to play solos exactly as they did on the records. Otherwise, some of the audience to a live performance would consider itself cheated or, worse, argue that the player wasn't the same one who had performed on the record.

If improvisation will not do as the sole defining characteristic of jazz, and if non-improvisation, as in solos by Louis Armstrong and Art Tatum, does not make it not jazz, then what does define it?

If it does not cease to be jazz because the soloist sometimes is not improvising, neither does it cease to be jazz because it is written. It would be difficult to argue that what McKinney's Cotton Pickers played wasn't jazz. The multi-instrumentalist and composer Don Redman — who wrote for Fletcher Henderson's band before Henderson did — became music director of the Cotton Pickers in 1927 and transformed it in a short time from a novelty group into one of the major jazz orchestras. And its emphasis was not so much on soloists as on the writing: Redman's tightly controlled and precise ensemble arranging, beautifully played.

McKinney's Cotton Pickers was based in Detroit, part of the stable of bands operated by the French-born pianist Jean Goldkette: his National Amusement Corporation fielded more than 20 of them, including one under his own name whose personnel included Frank Trumbauer, Bix Beiderbecke, Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey, Joe Venuti, and Spiegle Willcox (who is still playing). One of Goldkette's bands, the Orange Blossoms, became the Casa Loma Orchestra, with pioneering writing by Gene Gifford. Artie Shaw has argued that the "swing era" began as a popular musical movement not with Benny Goodman but with the Casa Loma. Also in Detroit, Redman was writing for the Cotton Pickers and Bill Challis for the Goldkette band, both bands influencing musicians all over America who listened to them on the radio. Gil Evans in Stockton, California, was listening to Gene Gifford's writing on radio "remotes" by the Casa Loma. Even the Isham Jones band of the 1930s was born in Detroit; it was actually organized by Red Norvo. Given all these factors, there is good reason to consider Detroit — awash in money from both the illegal liquor importation from Canada and the expanding automobile industry and willing to spend it freely on entertainment — the birthplace of the big-band swing era.

But the structural form of the "big band" must be considered the invention of Ferde Grofe’, who wrote for the Art Hickman band that was working in San Francisco and almost certainly was influenced by black musicians who had come there from New Orleans. Hickman hired two saxophone players from vaudeville to function as a "choir" in his dance band. The band caused a sensation, and Paul Whiteman was quick to hire Grofe’ to write for his band, as he was later to hire Bill Challis and various soloists who had been with Goldkette. The band of Paul Specht was also influential, through the new medium of radio broadcasting: its first broadcasts were made as early as 1920. Don Redman for a time worked in the Specht office, and it may well have been the value of his experience there that influenced Fletcher Henderson to hire him. Henderson also hired Bill Challis. Once Henderson got past his classical background and got the hang of this new instrumentation, he became one of the most influential — perhaps, in the larger scale, the most influential — writers of the era.

These explorers had no choice but to experiment with the evolving new instrumentation. There was no academic source from which to derive guidance, there were no treatises on the subject. Classical orchestration texts made little if any reference to the use of saxophones, particularly saxophones in groups. And these "arrangers" solved the problem, each making his own significant contribution. While Duke Ellington was making far-reaching experiments by mixing colors from the instruments of the dance-band format, the Grofe’-Challis-Redman-Henderson-Carter-Oliver axis had the widest influence around the world in the antiphonal use of the "choirs" of the dance-band for high artistic purpose; The instrumentation expanded as time went on. Three saxophones became four, two altos and two tenors, the section's sound vastly deepening when baritone came into widespread use in the 1940s. The brass section too expanded, growing to three trumpets and two trombones, then to four and three, and eventually four and even five trumpets and four trombones, including bass trombone.

This instrumentation may vary, and of late years its range of colors has been extended by the doubling of the saxophone players on flutes and other woodwinds, the occasional addition of French horn (Glenn Miller used a French horn in his Air Force band and Rob McConnell's Boss Brass uses two) and tuba, but structurally the "big band" has remained a superb instrument of expression to the many brilliant writers who have mastered its uses.

The big-band era may be over, but the big-band format is far from moribund. The "ghost" bands go on, though the revel now is ended, and their greatest actors are vanished into air, into thin air: Tommy Dorsey, Woody Herman, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and more. The Artie Shaw band goes on, though Shaw does not lead it. It is the only ghost band that has a live ghost. (Woody Herman seems to have invented the term "ghost band" and swore his would never become one. It did.)

Curiously, none of the ghost bands has the spirit, the feel, of the original bands. In ways I have never understood, the leaders of these bands somehow infused them with their own anima. Terry Gibbs has attested that sometimes, when the crowd was thin, Woody Herman would skip the last set and let the band continue on its own; and it never sounded the same as when he was there, Terry said. The current Count Basie band does not have the "feel" of the original. There are of course two things without which a Basie band is not a Basie band: Basie and Freddie Green. But those conspicuous omissions aside, Basie was able to get a groove from that band that eludes his successors.

Far more interesting than the ghost bands are those regional "rehearsal bands" that spring up all over the country, and indeed all over the world, or the recording bands assembled to make albums and, afterwards, dissolved— at least until the next project.

As we begin the twenty-first century, the evolution of jazz as the art of the soloist has slowed and, in the example of many young artists imitating past masters, ceased completely. There is an attempt to institutionalize it in concert halls through of repertory orchestras such as that at Lincoln Center led by Wynton Marsalis, the Liberace of jazz, and a brisk concomitant interest in finding and performing, when possible, the scores of such "arrangers" as George Handy.

There is an inchoate awareness that it somehow isn't quite kosher to imitate the great soloists of the past, though that hasn't deterred some of the younger crop of players from swiping a little Bubber Miley here, a little Dizzy Gillespie there, but it is all right to play music by jazz composers of the past, because written music is meant to be re-created by groups of musicians. And so the emphasis in the current classical-ization of jazz is to a large extent on the writers for past jazz orchestras. In this jazz is being institutionalized as "classical" music has been, the latter for the good reason that Beethoven couldn't leave us his improvisations, he could leave only written music to be re-created by subsequent players.

Much of this re-creative work is rather sterile. It lacks the immediacy, and certainly there is none of the exploratory zeal, that this music had when the "arrangers" first put it on paper. The new stuff being composed and/or arranged is much more interesting. And in any case, all too much of it is focussed on Duke Ellington. This incantatory fervor for Ellington has precluded a fitting concert recognition of Fletcher Henderson, Sy Oliver, Eddie Sauter, Ralph Burns, Bill Finegan, Billy May, and so many more who certainly deserve it. Unnoticed even by the public who admired them, these writers ("arrangers" seems a pathetically inadequate term) were building up a body of work that is not receiving the homage that is its due.

Thirty years ago, it seems to me, the writers in the jazz field were not taken seriously at all by some people. All was improvisation, the illusion being that jazz was fully improvised, rather than being made up of carefully prepared pieces of vocabulary, what jazz musicians call "licks"— chord voicings, approaches to scale patterns, and the like.

The influence of the big-band arrangers has now spread around the world. The format itself survives, of course, though rarely in full-time bands. It is found in the work of certain bands that come together from time to time, such as in the Clarke-Boland Big Band, now alas gone, based in Germany and led by the late Kenny Clarke and the wonderful Belgian arranger and composer Francy Boland. It is encountered today in the Rob McConnell Boss Brass in Toronto, and in Cologne in the WDR (for Westdeutsche Rundfuk) Big Band. Some years ago, I saw a Russian television variety show that included a big band, playing in the American style — not doing it well, to be sure, but doing it. The format survives in countless bands imitating Glenn Miller.

With the end of the big-band era, various of the arrangers for those bands found work elsewhere. Many of them began writing for singers. Marion Evans, alumnus of the postwar Tex Beneke-Glenn Miller band, wrote for Steve Lawrence, Tony Bennett, and many others. So did Don Costa, who wrote for, among his clients, Frank Sinatra. Sinatra's primary post-Dorsey arranger was Axel Stordahl and, later, Nelson Riddle, alumnus of the Charlie Spivak band. Peter Matz, alumnus of the Maynard Ferguson band, wrote for just about everybody, as did the German composer Claus Ogerman, particularly noted for his arrangements of Brazilian music. On any given work day in the 1960s, musicians were rushing around New York City and Los Angeles to play on these vocal sessions, a last hurrah (as we can now see) for the era of great songwriting, a sort of summing up of that era, the flower reaching its most splendid maturity just before it died.

Some of the arrangers, for a time, got to make records on their, instrumental albums in which they were allowed to use string sections. Among them were Paul Weston (whose deceptively accessible charts are of a classical purity), Frank de Vol, Frank Comstock, and most conspicuously Robert Farnon.

Many of these arrangers and composers began to influence motion picture music. They turned to film (1) for money, and (2) for a broader orchestral palette. They included Farnon, Benny Carter, Johnny Mandel, Billy Byers, Eddie Sauter, George Duning, Billy May, Patrick Williams, Michel Legrand, Allyn Ferguson, John Dankworth, Dudley Moore (whose gifts as a composer were eclipsed by his success as a comedian and actor), Johnny Keating, Pete Rugolo, Oliver Nelson, Roger Kellaway, Lennie Niehaus, Frank Comstock, Shorty Rogers, Lalo Schifrin, Tom Mclntosh, Quincy Jones, J.J. Johnson, Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn, Mundell Lowe, and Henry Mancini who, with his Peter Gunn scores, did more to make jazz acceptable in television and movie music than anyone else in the industry's history. That is a consensus among composers.

These people profoundly affected film scoring, introducing into it elements of non-classical music that had been rigorously excluded, excepting little touches in the scores of Alex North and Hugo Friedhofer and others and the occasional use of an alto saxophone to let you know that the lady in the scene was not all she should be. The medium had been dominated by European concert-music influences. Early scores appropriated the styles and techniques of Tchaikovsky, Mendelssohn, Brahms — and sometimes their actual music. Later the twentieth-century Europeans had an influence, up to and including Bartok and Schoenberg, though probably no one was ripped off as much as Stravinsky, whose 1913 Rite of Spring is still being quarried by film composers. In his scores for the TV series Mission: Impossible, Lalo Schifrin used scale exercises he had written for his teacher Olivier Messaien at the Paris Conservatory.

The appeal of film scoring to "jazz" composers and arrangers is obvious. Most of them had extensive classical training, and strong tastes for twentieth-century European composers, especially Ravel, Debussy, Stravinsky, and Bartok. (William Grant Still, essentially a classical composer but also an arranger who scored Frenesi for Artie Shaw, studied with Edgard Varese as far back as 1927.) This familiarity with the full orchestra inevitably led to a sense of restriction with the brass-and-saxes configuration of dance bands. Despite a general hostility of many jazz fans toward string sections as somehow effete, many of the leaders wanted to use them, and some tried to do so, among them Artie Shaw, Tommy Dorsey, Gene Krupa, and Harry James.

These experiments were doomed for two reasons. The first was a matter of orchestral balance. A 100-member symphony orchestra will have a complement of as many as 60 string players. This is due to complex mathematical relationships in acoustics. Putting two instruments on a part does not double the volume of the sound. Far from it. To balance the other sections, a symphony orchestra needs 60 string players. But the instruments of a standard dance-jazz band can drown even the 60 strings of a symphony orchestra, as appearances of jazz bands with symphony orchestras have relentlessly demonstrated. (In the recording studio, of course, a turn of the knobs will raise the volume of the string section to any level desired.)

As far back as the 1940s, such arrangers as Paul Weston, Axel Stordahl and, in England, Robert Farnon used their work with singers as a means to explore string writing. Indeed, strings had been used in the 1930s and early '40s by singers such as Bing Crosby. But the uses of strings behind singers became much more subtle and sophisticated in the '40s, '50s, and '60s with the writing of such arrangers as Nelson Riddle, Marion Evans, Don Costa, Marty Manning, and Patrick Williams. Some jazz fans abhorred the string section; musicians know there is no more subtle and transparent texture against which to set a solo, whether vocal or instrumental.

No bandleader could afford the large string section needed to hold its own with dance-band brass-and-saxes. And so those bands who embraced them in the 1940s tried to get by with string sections of twelve players or fewer — and on the Harry James record The Mole, there are only five. There was something incongruous, even a little pitiful, in seeing these poor souls sawing away at their fiddles on the band platform, completely unheard.

During World War II, with his U.S. Army Air Force band — when money was no object, because all his players were servicemen — Glenn Miller was able to deploy 14 violins, four violas, and two celli, a total of 20 strings. But this was still hopelessly inadequate against the power of the rest of the band.

It was in film that former band arrangers were able to experiment with the uses of jazz and classical orchestral techniques, for the money they needed was there, along with a pool of spectacularly versatile master musicians who had been drawn to settle in Los Angeles for its movie and other studio work. To this day, some of the most successful fusions of jazz and classical influences have been in the movies, including such scores as Eddie Sauter's Mickey One and Johnny Mandel's The Sandpiper.

That era is gone. Gone completely. The singers of quality are of no interest to the record companies; neither are the songs from the great era of songwriting, the songs of Kern, Porter, Warren, Rodgers and Hart, Carmichael, Schwartz.

Thus the superb orchestras that used to be assembled in the 1960s to record such songs with such singers are a thing of the past. Even in the movies, the change has been total. There are no longer excellent studio orchestras on staff, and orchestral writing of any kind is comparatively rare in films. The producers long ago discovered that they could use pop records as scoring. Pop records and synthesizers. The long-chord drone of synthesizers, not even skillful but sounding like slightly more developed Hammond organs (which were used for dramatic underscore in the old radio soap operas) are heard in movies today. Only a handful of composers, and "real" musicians, are able to derive their living from movie work, or from recording.

A story circulated rapidly among musicians a few years ago. A musician was called to play on a recording session that utilized a large "acoustic" orchestra. Afterwards he was asked what it was like.

He said, "It was great. We must have put two synthesizer players out of work."

The remark is usually attributed to Conte Candoli.

Conte says he didn't say it. "But I wish I had."

A film composer was asked to submit some themes to the director of a movie. He gave him five. The director waxed enthusiastic. The next day he told the composer he was throwing out three of the themes. Why?

The director said he had played them for his daughter, and she had disliked those three.

"How old is she?" the composer asked.

"Five."

The brilliant comedy writer Larry Gelbart, creator of M.A.S.H. has said that in the movie industry today, you're dealing with fetuses in three-piece suits. It must be remembered of the current crop of executives in the entertainment industry that not only did they grow up on rock-and-roll and its branches, in many cases their parents grew up on it.

The president of the movie branch of Warner Bros, has stated publicly that he shows script ideas to his fourteeen-year-old son. If his son doesn't like them, he throws them out.

Yes, the era is over.”

.jpg)