© -Steven Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

For obvious reasons, drummers [even ex-drummers] love Latin or Afro-Cuban Jazz.

I mean, c’mon, Latin rhythm sections never run out of things to hit, bang, slap, crash or whack – a drummer’s delight, es verdad?

When I was first learning to play drums as a young man in Southern California in the late 1950’s, I was fortunate to play in a series of rehearsal bands. These were usually led by aspiring or, in some cases, established composer-arrangers who wanted an available vehicle in which to hear their “charts” [musician-speak for arrangements].

One of these aggregations was headed-up by a Hispanic trombonist from East Los Angeles who one day brought along to a rehearsal a transcription of Johnny Richards’ arrangement of Los Suertos de los Tontos [“Fortune of Fools”] that he had taken note-for-note from the Stan Kenton recording – Cuban Fire! [Capitol CDP 7 96260 2]. Where there is a will there’s a way?

He also brought along with him two of his friends who were adept Latin percussion players.

That was it for me; I was hooked then, and have been ever since, on the power, the majesty and the excitement of Latin Jazz. What a wild ride!

While playing the 6/8 triplet figure on the bell of the cymbal that forms the underlying beat of the tune, I was pushed into a state of total elation by the incessant driving beat of the Latin percussionists who alternated between bongos and conga drums, timbales, cow bells, clave and various types of shakers throughout the 4 minutes or so of the tune.

Prior to that time, I had heard small group versions of Latin Jazz as played by quintets led by pianist George Shearing and vibist Cal Tjader, respectively.

But that had not prepared me for what happen with this music once trumpets, trombones and saxophones were added to the mix.

Seeing that my enthusiasm for the music was almost palpable, the Latin percussionists invited me to come by and listen to the ten-piece group that they performed with on a regular basis at a club called Virginia’s in the MacarthurPark region of Los Angeles.

Needless to say, I drove down to the club that evening and was an almost constant presence there for about 6 months during which they taught me everything about the right way to play what they referred to as “Afro-Cuban rhythms.”

Dancing to the rumba and the mambo were very popular in the 1950s and most major cities had night clubs that catered to this clientele featuring music by what today would be called salsa bands.

During the early days of my Latin Jazz musical quest, I’d come home most nights with my head reeling from listening to the punctuating brass instruments [the drums were set on a riser just below the trumpets and trombones] and my hands would be bleeding until I had built up the necessary callous from playing the conga drums.

I didn’t care; I was a young man in what I thought then was “Drummer’s Heaven.”

I soon learned, however, that playing Latin Jazz or Afro-Cuban rhythms was a lot more involved than hitting, banging, slapping, crashing or whacking everything in sight.

There were conventions or rhythmic rules and these had to be unwaveringly adhered to or else the back of my hands would be bleeding, too, from the whaps they received from the timbales sticks [actually small, wooden dowels which are not tipped like regular drum sticks] of my unyielding teachers.

“Hey, man, play it right; you’re screwing the rest of us up!”

For while it may sound like a lot of clap trap to the uninformed ear, the Latin rhythm section is actually a well-oiled machine with everything in its place. When done correctly, the rhythms, counter-rhythms and accents played in combination by the conga and bongo drums, timbales and a variety of hand-held percussion instruments create a fluid, rippling foundation over which the melody glides.

While jazz rhythms are swung, most Latin jazz tunes have a straight eighth note feel. Latin jazz rarely employs a backbeat, using a form of the clave instead.

Most jazz rhythms emphasize beats two and four. Latin jazz tunes rely more on various clave rhythms, again depending on regional style.

Since the underlying “feel” of Latin or Afro-Cuban Jazz relates to the clave, perhaps a word at this point as to its meaning, role and its relationship with the instruments, compositions and arrangements

Clave in its original form is a Spanish word and its musical usage was developed in the western part of Cuba, particularly the cities of Matanzas and Havana. However, the origins of the rhythm can be traced to Africa, particularly the West African music of modern-day Ghana and Nigeria. There are also rhythms resembling the clave found in parts of the Middle East.

By way of background and very briefly, there are three types of clave.

The most common type of clave rhythm in Latin Jazz is the son clave, named after the Cuban musical style of the same name. Below is an example of the son clave rhythm in Western musical notation.

Because there are three notes in the first measure and two in the second, the above is said to be in the 3:2 direction or forward clave. The 2:3 clave is the same but with the measures reversed [i.e.: reversed clave].

Another type of clave is the rumba clave which can also be played in either the 3:2 or 2:3 direction, although the 3:2 is more common. Here is an example of its notation:

There is a third clave, often called the 6/8 clave or sometimes referred to as the Afro Feelclave because it is an adaptation of a well-documented West African [some claim Sub-Saharan] 12/8 timeline. It is a cowbell pattern and is played in the older more folkloric forms of Cuban music, but it has also been adapted into Latin Jazz.

Below are the three major forms of clave, all written in a 3:2 position:

The choice of the direction of the clave rhythm is guided by the melody, which in turn directs all other instruments and arrangements.

In many contemporary compositions such as those recorded by Mongo Santamaria or the aforementioned Shearing & Tjader groups, the arrangements make use of both directions of the clave in different sections of the tunes.

As far as the type of clave rhythm used, generally son clave is used with dance styles while rumba and afro are associated with folkloric rhythms.

To re-emphasize a point before moving on, while allowing for some embellishment, these clave rhythmic patterns must be strictly adhered to by the percussionists in the playing of Latin Jazz to keep the music controlled and grounded, while at the same time, flowing.

To the uninitiated, Latin Jazz rhythm sections might sound more like controlled chaos, but when it all comes together properly it is a thing of beauty, especially as one’s ear becomes more informed.

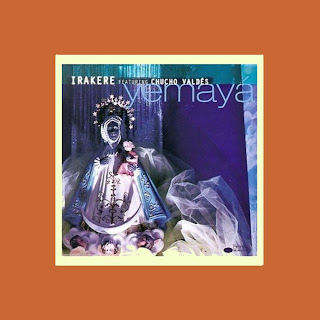

The first time I heard the Cuban Jazz group IRAKERE’s music, I was absolutely overwhelmed by how well all of these rhythmic conventions were honored thus providing a platform for a music rich in passionate intensity and melodic intrigue.

"IRAKERE"is the Yoruba word for “vegetation.” And “Yoruba” refers to an ethno-linguistic group native to West Africa, but the dialect is also spoken in some parts of Cuba. I have no idea as to the idiomatic hip meaning of IRAKERE, but I certainly hope to find out one day what arcane symbolism may lurk behind the name of the band.

This blending of Cuban folkloric elements with indigenous Cuban and West African rhythms perhaps indicates that the 1950’s term of Afro-Cuban Jazz may be a more appropriate appellation for many forms of Latin Jazz today.

However, the influx into the United States during the last quartet of the 20th century of large populations from Puerto Rico, parts of the Spanish Caribbean and Mexico, that is to say, immigrants of ethno Hispanic origin, may be responsible for the adoption and current prevalence of the more generic term – Latin Jazz.

For all intents and purposes, we will use the terms Afro-Cuban and Latin Jazz interchangeably.

As is often the case in life, my musical encounter with IRAKERE happened quite by accident.

For as long as I can remember, I was always a avid listener of Southern California DJ Chuck Niles’ FM Jazz radio program. And although he moved around to various stations and time periods over the years until his death in 2004, I always searched out Chuck’s programs because I learned so much from them.

Chuck had great reverence for what he termed “straight-ahead Jazz,” in whatever form and from whatever period. Whether it be the bebop the cool sounds or hard bop, as long as you could snap your fingers to it, Chuck loved it. Chuck was such a devotee of straight-ahead Jazz that composer-arranger Bob Florence nicknamed him “Bebop Charlie” and pianist, composer and band-leader Horace Silver called him “The Hippest Cat in Hollywood.”

Another aspect of the music that he particularly loved was Jazz saxophone. He was a great admirer of Sonny Rollins, Jackie Mclean Gerry Mulligan and most especially of Phil Woods [like Chuck, a native of Springfield, MA], to name just a few practitioners of this art. Thanks to Chuck, I first heard the brilliant British tenor saxophonist Tubby Hayes on one of his programs and have had a life-long interest in his music ever since.

Chuck was always bringing new music and new musicians to my attention and so it is no surprise that it was during one of his FM radio broadcasts that I had my first sampling of the Latin Jazz music of the Cuban group IRAKERE in the late 1970’s.

In talking with Chuck about the group many years later, not surprisingly, he mentioned that what first drew him to IRAKERE’s music was the alto saxophone playing of Paquito D’Rivera [who like the group’s trumpeter Arturo Sandoval, later immigrated to the USA, and each have since become star players in their own right].

Chuck also explained that it was around this time that his fascination with Latin Jazz really took off. Chuck would later embrace his Latin DJ radio colleague, Jose Riso, who not only taught him a great deal about Latin Jazz, but also greatly improved his pronunciation of Spanish names.

Thanks to a thaw in the seemingly always-strained relationship between the governments of Cuba and the United States, IRAKERE was allowed to appear at the Newport Jazz Festival in the summer of 1978 where the group really broke-it-up. This appearance was followed shortly thereafter by another crowd-pleasing performance at the Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland.

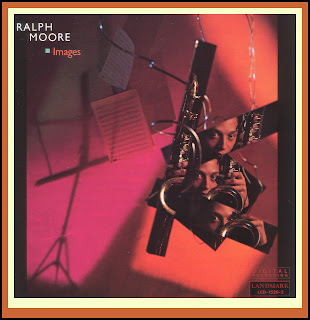

One result of these smashing performances was a recording contract with Columbia Records which released both IRAKERE [JC 35655]and IRAKERE 2 [JC 36107]in 1979.

It was music by the group from these recordings that I had heard on Chuck Niles’ radio program and which really impressed me.

Unfortunately, for a variety of business and political reasons, Columbia dropped IRAKERE from the label, and although other labels did issue records by the group, they did so in a desultory manner and through limited channels of distribution.

To compound matters, the defections of Paquito D’Rivera and Arturo Sandoval to the United States in the early 1980’s along with a resumption of the strained relationship between the Cuban & US governments following the mass exodus of the Mariel boatlift in 1980, meant that IRAKERE was not be able to return to the United States again until 1996.

Fortunately, in the meantime, the advent of the computer disc helped keep available the music of various iterations of the group over the years ensuing years since it erupted on the world scene with the two 1978 performances by the original group.

As underscored in the following writings, the heart and soul of IRAKERE is the much revered Jesús Dionisio “Chucho” Valdés, son of the legendary pianist Bebo Valdés, and in his own right a pianist whose technical skills rival those of Art Tatum and whose composing and arranging abilities are formidable in the extreme.

From any number of perspectives, “Chucho” Valdés is an artistic genius.

The music of IRAKERE is not for the faint-of-heart. Much of it is effervescent and loud. And there are some aspects of the group’s music that may not appeal to Jazz purists such as the use of electronic keyboards, bass and guitar. And the occasional use of Rock-inflected rhythms may raised the dreaded specter of “Fusion” for some.

However, if Afro Cuban Jazz is music that you find pleasure in, then it doesn’t get any better than IRAKERE: the soloists are scintillating, the extended unison phrases that Valdés constructs for the horns are some of the best you’ve ever heard since Charlie Parker & Dizzy Gillespie last played together, the ballads and romantic dance tunes are lushly arranged and caringly played and the Spanish words fuego [fire] and caliente [hot] barely come close to describing the pulsating power generated by the group’s Latin rhythm section.

The ranking expert on IRAKERE is Leonardo Acosta, a Cuban musicologist who is an authority of the history of Jazz in Cuba in general. Luis Tamargo and Robin A. Vasquez are also knowledgeable on both subjects.

After some brief “opening remarks” by John Storm Roberts as taken from the insert notes to IRAKERE’s first Columbia album, we will turn to these authors for more insightful and expert information on the group including some of their select discography.

Hopefully, too, the music about IRAKERE and these writings about it will go a long way toward redressing the lack of awareness that the music of Cuba and the musicians of Cuba have had on the development of Jazz, then and now.

For some of the younger readers of JazzProfiles, please keep in mind that the world was a different place when IRAKERE first came on the scene in the 1970s with the paranoia of the Cold Warstill very prevalent. As a result, the ability to actually know what was going on in some Communist or, as they were often referred to, “Iron Curtain” countries was still a very difficult proposition – at best.

IRAKERE

© -John Storm Roberts, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“For years now the buzz has been on, in the places where New York’s Latin musicians hang out: ‘Wait ‘till Cuba erupts.’ Rumors of Afro-Cuban drums ensembles teamed with synthesizers, of rock guitars among the charanga groups’ flutes and fiddles. Some hard evidence too – a test pressing bought in Martinique, a dubbing from a shortwave broadcast picked up in Miami. More recently, as the curtain slowly begins to lift and people traveled back and forth, rumors gave way to a name: IRAKERE. Probably, the hottest, and deepest, and most creative band on the Cuban scene today.

So, you may ask, what?

So, that means a major part of the U.S. music scene is likely to be turned on its ear. Not only the hot, creative Latin music that has come to be called “salsa,” but its great hybrid, Latin-jazz, and – through them – the rhythm-and-blues and funk and disco styles that have been so totally revolutionized by the Latin tinge over the past near-decade.

“Latin” music has been the single most important outside influence on American popular music over the last 100 years. Almost every decade since World War One has seen styles from Cuba, Mexico, Brazil or elsewhere sweep the United States: the tuen-of-the-century habanera; the teens-and-twenties Argentinean tango; the 1930’s rumba; the 1940’s conga and samba; the 1950’s mambo and chachacha; the 1960’s bossa nova. These were not marginal fads, but mass movements. Out of 163 popular melodies given more than one million performances since 1940, 23 – almost one in seven – were Latin in origin or inspiration, most of them Cuban. Only half as many jazz, blues and soul numbers combined, and around 19 country [&western] songs, have made the same list.

For 60 years, in fact, ‘Latin’ music has been a fundamental part of every aspect of U.S. popular music history. And without minimizing the significant of Brazil and Mexico, the most important influence by far has been Cuban.

And that’s only the U.S. Not only do the Latin shadings tint the international pop scene from Paris to Athens to Tokyo, but an entire modern urban African music, with variants from Lagos to Mombassa, owns much of its existence to two roots – African and Cuban. And the prime exponent of contemporary Cuban music is IRAKERE.”

© -Leonardo Acosta, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“Around 1972, some of the members of the Cuban Modern Music Orchestra decided to form their own group, and by 1973 it had been organized into what is now known as IRAKERE. When these musicians, all impeccable soloists, left the best orchestra in the country, they had but one purpose in mind: to put all their efforts into what could be called ‘experimenting,’ joining a trend begun by others who were trying to renovate popular music.

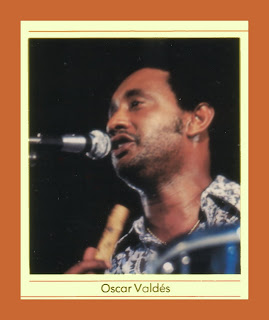

Chucho Valdés [piano] and Paquito D’Rivera [alto sax & clarinet], both composers and arrangers, were, from the beginning, the main inspirers of IRAKERE. Oscar Valdés would be in charge of giving a different personality to the percussion section, adding to it his knowledge of ancesteral songs in African language, one of the most important and least known forms of music of the Afro-Cuban musical heritage. Other members of the group also come from Cuban Modern Music Orchestra: Emilio Morales [guitar], Carlos del Puerto [bass], Enrique Pla’ [drums] and Arturo Sandoval and Jorge Varona [trumpets]. and Arturo Sandoval and Jorge Varona. Later additions were Carlos Averhoff tenor & baritone sax] Jorge Alfonso and Armando Cuervo [percussion] to complete the group as it is today

![]()

IRAKERE has two advantages over all the other groups who have a similar musical approach: the virtuosity of its soloists, who are excellent improvisers, and then, the cohesion which comes after playing together for many years. Chucho, Paquito and Carlos Emilio have been associated almost since the beginning of their professional careers: first in the Havana Musical Theatre Orchestra and later on in a group that was led by Chucho, which had as a vocalist Amado Borcela (Guapacha’), who has since died, and with whom they made a number of records for EGREM, earning quite a lot of popularity in the sixties. Later on they formed different quartets and quintets (with Pla’, Oscar and sometimes with Sandoval or Varona) to play at sporadic concerts and festivals in Cuba and abroad. Their most outstanding performance outside of Cuba was during the 1970 Polish Jazz Festival, where the Cubans were heard and praised for the first time by renowned jazz artists like Dave Brubeck and Gerry Mulligan.

![]()

But let us leave IRAKERE's past history and come to present times. After having become the most brilliant and solid group within the new stream in Cuban music, they met, during the [one and only] Jazz Cruise's stay in Havana in 1977, [such luminaries as] Stan Getz, who had come to Cuba often during the fifties, and Dizzy Gillespie, who strangely had never visited the country of his collaborator, Chano Pozo. The interest and enthusiasm that IRAKERE stirred up among the members of the Cruise - including musicians, jazz critics and producers - was like a preview of what would happen during the group's tour through the United States and Switzerland during June/July, 1978, and outstanding performances at the Newport and Montreux Jazz Festivals.

The press reviews that appeared in The New York Times, and San Francisco Examiner and Billboard, were very enthusiastic about IRAKERE, but a few questions arose that showed that there was some confusion. Is it really jazz that IRAKERE plays? Has it anything to do with ‘salsa’? Can the group be classified as ‘Latin-jazz-rock'’ or as '’Latin-fusion’' or '’salsa-fusion’?

The truth is that although the majority of the IRAKERE musicians have played jazz for many years, they have more experience and more solid roots in Cuban music. And the presence of Cuba in IRAKERE is not only in its percussion, it is also in its way of playing: in the phrasing, in the attack and sense of rhythm of the soloists, as well as in whole passages.

![]()

Our novelist, Alejo Carpentier, who is also a renowned authority on music, has said that Cuban popular music is "the only music that can be compared with 'Jazz in the 20th century.’ Is it not strange that these two musical forms have been compared so frequently? Their affinity comes from before the existence of jazz as such. We know all about the history of the beginnings of jazz, but we don’t always associate it with the ending of slavery in Cuba, between 1880 and 1889, and the massive immigration of black Cubans, free but jobless, to places like New Orleans. Neither is it unusual that along with French and English names, one finds among the first jazz musicians names that show their Spanish roots (Lorenzo Tio, Luis Tio, Manuel Perez, Willy Marrero, Paul Dominguez), nor that Jelly Roll Morton, when asked about where jazz came from, included Cuba among its places of origin.

More well known are the international influences of the habanera and the rumba, until we come to the 1940s and 1950s, the Cubop era. During this period, the impact caused by the meeting between Chano Pozo and Dizzy Gillespie can be added to the influences of Machito, Perez Prado, Mario Bauzá, Mongo Santamaria, Chico O'Farrill and many others. The "fusion'' between elements of jazz and Cuban music has a long history having nothing to do with the more recent merging of jazz and rock, which sometimes adds certain so-called ''Latin'' elements which are in reality, Afro Cuban or Afro-Caribbean. As far as salsa is concerned, it is 99 percent Cuban music of the '40s and '50s. This is why if IRAKERE are jazz musicians, they are so in a very substantially Cuban way.

If Chucho Valdés was familiar with the piano styles of Horace Silver or Bill Evans more than ten years ago, he also knew the peculiarities of the son, the contradanza and the danzón. At times we here reminiscences of Art Tatum in some passages, yet the other side of Chucho's style is given by his mastery of Cubanclassical piano: Cervantes and Samuell in the19th century and Lecuona in the 20th, and in a

more popular vein, Antonio Maria Romeu. Going down this road, who knows if, with the coming of IRAKERE onto the musical scene, we are getting to the roots and to the redevelopment, with a newer viewpoint, of practically inexhaustible materials.

Chucho's compositions, as well as those of other members of the group, reflect a receptiveness; to what is going on internationally, including free jazz and the so-called European musical vanguard. They put these to work as a form of personal expression, underlined by the knowledgeable use of rhythms that have African origins and which are mixed and renovated with great originality. One of the

contributions has been to incorporate, into a musical context that once only accepted Congo and Dahomeyan elements, the intricate and vigorous Yoruba and Carabali rhythms which have been well known in Cuba but which had not been "integrated'' into the mainstream of our music. Another characteristic of these compositions are the frequent changes in time and atmosphere, a typical element in Yoruba music.

‘Missa Negro’ ("Black Mass"), is perhaps the best example of this, although it can also be heard in ‘Ilya,’''Aguanile’’ and others.

As to the individual contribution by each soloist, we must let them speak for themselves. You can't deny Paquito D'Rivera and Arturo Sandoval owe a lot to Parker and Gillespie, but can there be a more logical debt?

In Paquito's explosive sense of humor, the fierce intensity of Arturo, and Chucho's controlled lyricism, we find very personal facets in their playing. Like IRAKERE, there are many other young Cuban musicians who also play jazz in a style deeply rooted in Afro-Caribbean music and who at the same time have definite personal styles. IRAKERE is an outstanding example within a real musical ‘explosion.’ Which is saying a lot.”

IRAKERE 2

© -Leonardo Acosta, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“The impact the IRAKERE group caused in the United in 1978 among jazz musicians, critics and fans was an outstanding event in the history of jazz and its relationship to Cuban musk and musicians since the forties, when Chano Pozo appeared on the jazz scene and people started to talk about ‘Cubop.’ The mingling of influences between Cuban music and jazz are, of course, older and deeper, and the examples we've mentioned are only two peaks, two culminating moments in the intense interaction and cultural borrowings that has taken place among these two Afro-American musical forms.

![]()

Although Chano Pozo, Machito, Mario Mario Bauzá, Mongo Santamaria, Perez Prado and other Cuban musicians have bad a definite influence on what is known as ‘Latin Jazz,’ they, themselves, are not strictly jazz musicians but only followers and developers of Afro-Caribbean music. IRAKERE, being both expert jazz and Afro-Caribbean musicians, stands out as an exception. It's not only because Chucho Valdés has been influenced by Art Tatum, Horace Silver and Bill Evans; or that Paquito D’Rivera has listened to Charlie Parker, Jackie McLean or Phil Woods; or Arturo Sandoval to Dizzy Gillespie, Maynard Ferguson or Clifford Brown. Reality is more complex. For instance, in the United States it is not known that since the twenties there has been a continuing jazz tradition in Cuba, and the first jazz experiences the members of IRAKERE had were during jam sessions where they heard older Cuban musicians take off in pure jazz style. Different articles and reviews have talked about the presence of Cuban-born musicians during the beginnings of jazz, but it was not until the twenties, when thanks to the growth of radio, and especially of the recording industry, that the interchange of ideas and sounds between Cuba, the States and other countries of the hemisphere like Argentina, Mexico and Brazil, became more intense. During those years a new rhythm was sweeping all over the island and especially in Havana: it was the son, which has played a role in Cuban popular music similar to that played by the blues in North American music, acting at different moments as catalyzer and revitalizer of different styles and trends but keeping the original form.

![]()

Around 1925, the first jazz groups came to Cuba. According to musicians interviewed by jazz critic Horacio Hernández, the first jazz group organized in Cuba was a sextet directed by violinist Jimmy Holmes, and included two saxophones, banjo, drums and percussion. A year later more groups were formed, made up entirely of Cuban musicians, like the Teddy Hernández quartet (violin, sax, piano and drums), and by the end of the decade one could hear in Cuba excellent jazz musicians like Alberto Jiménez Rebollar (drums), Cecilio Curbelo (piano), Alberto Socarras (flute), JesusJesús Pia (violin), Rene’ Oliva (trumpet), Amado Valdes (alto sax), Armando Romeo (tenor sax) and Mario Bauzá, a clarinetist, who later became well-known in the States as a trumpet player for the Chick Webb, Cab Calloway, and Machito orchestras.

The thirties were the golden years of the big bands, d it wasn’t long before they began to appear in Cuba. By 1933 saxophonist and arranger Armando Romeu had organized his first jazz band. Thirty-four years later, in 1967, Romeu would be the first director of the Orquesta Cubana de Musica Moderna, which had eight of the eleven members of IRAKERE. Although practically unknown outside of Cuba, Romeu enjoyed a long career as a musician and his name appears in Leonard Feather's The Encyclopedia of Jazz. During the thirties a very important development took place, and that was the "Cubanizing" of the jazz band. In other words, the using of a jazz band to play Cuban dance rhythms like the son, the guaracha the rumba and the danzón.

Among the better orchestras of the time, we can find that of alto saxophonist German Lebatard, Rene Touzet's, the Bellamar Orchestra, the Casino de la Playa Orchestra, the band led by guitarist Isidro Perez, the Palau Brothers Band, and the Riverside Orchestra. All of these organizations opened the way for what was to come in the late forties:Dámaso Pérez Prado and his explosive combination of the jazz band and the rhythmic elements used in the danzón, especially those innovations used by the arranger Orestes López. The “Cubanizing” of the big jazz band continued into the fifties, culminating in the orchestra of singer Benny Moré which introduced the spirit and the roots of son montuno, a rural form that had sprung up in the eastern end of the island fifty years earlier.

[Montuno = mountain; the phrase son montumo probably referring to that form of son clave that originated in the mountanous Oriente province in eastern Cuba]

![]()

If the first Cuban arrangers and instrumentalists were influenced by musicians like Fletcher Henderson, Duke Ellington, Earl Hines, Louis Armstrong, Johnny Hodges, Sonny Greer and Coleman Hawkins, the ‘bop revolution’ caused an even greater rapprochement between our music and jazz when men like Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Max Reach, Kenny Clarke, Art Blakey, and many others, would listen to ‘Latin’ rhythms with as much interest as the Cubans were beginning to have for the melodic and harmonic innovations of hop. By 1947 names like Rafael Hernández (bass), Fausto Garcia (drums), Isidro Pérez (guitar), and especially Arturo "Chico" O'Farrill (trumpet), were becoming prominent. O'Farrill later on began arranging for Armando Romeo and won international recognition as an arranger for Benny Goodman, Dizzy Gillespie, Stan Kenton, Count Basie, and for his own band. Also outstanding were tenor saxophonist Gustavo Mas, who later played with Woody Herman (a solo of his can be heard in ‘Gus Is The Boss’), and Jose Silva (Chombo), another tenor sax who cut a few sides with Cal Tjader. Among the best Cuban jazz pianists we find the very versatile Mario Romeo and Frank Emilio, who like nobody else has combined Shearing and Peterson along with Cuban piano styles.

In Cuba, like elsewhere, jazz enthusiasts have always been few but faithful. Towards the end of the fifties, a group of musicians and fans organized the Club Cubano de Jazz, a non-profit association that lasted into the sixties. Thanks to the Club, a number of musicians traveled to Cuba, among them Zoot Sims, Philly Joe Jones, Kenny Drew, Vinnie Tanno, Mundell Lowe, Bill Barron, Harold McNair, Eddie Shu, Tom Montgomery, Fred Crane, and others, all of them playing alongside of Cuban musicians. Stan Getz, Buddy Rich, Milt Jackson, Conte Candoli, Shelly Manne, Sarah Vaughan and her trio (Jimmy Jones, Richard Davis and Roy Haynes) also visited Havana, increasing the interchange of ideas and musical experiences.

![]()

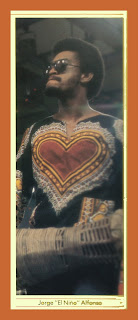

Many Cuban musicians tried their for the first time during concerts sponsored by the Club Cubano de Jazz. Among the first to stand out was Carlos Emilio Morales, IRAKERE’s guitarist, while Paquito D'Rivera wouldn't miss a session even though he was a small boy. During the sixties, Carlos Emilio got together with a young pianist, Chucho Valdes, and other older musicians to play at concerts. Later on, Chucho, Paquito and Carlos Emilio found themselves together in the orchestra of the Teatro Musical de la Habana which had just been created. During those years Jorge Varona began to be noted as a jazz trumpeter and Oscar Valdes as a percussionist. They all later on became founders of the Orquesta Cubana de Musica Moderns (1967), which had as directors Armando Romeu, the late Rafael Somavilla and finally Paquito. From this new encounter the idea of creating a new group sprung up, and IRAKERE was formed including some of the youngest and most brilliant musicians of the orchestra, like Arturo Sandoval and Enrique Pla’.

![]()

After their success in Cuba, Europe and the 1978 Newport Jazz Festival, IRAKERE showed they had something new to say in a style as deeply rooted in Cuban traditional music as in straight jazz, in spite of their experiences in electronics, a thing that has frustrated many top ranking jazz musicians. If IRAKERE has been able to overcome electronics creatively, this is due mainly to the freshness with which they approach their material and to the integration they have achieved fusing elements of different Afro-American musical traditions.

Before IRAKERE, popular Cuban music used mainly the tumbadora and the bongo’ as percussion instruments, filling in with others like the clave, the timbales or pailas [‘Paila criolla’ is the term given to a shallow single-headed drum with metal casing, invented in Cuba] and the güiro.

Beside these, IRAKERE also uses instruments of Afro-Cuban religious and social rituals like theBatá drums or the chekere which not only implies a new sound but also a totally new way of conceiving the relationships between the intricate poly-rhythmic passages, the horns ensemble work, the phrasing of the improvisations and the actual dynamics of each piece.

Rhythms in 6/8 time assert themselves over the more classical 4/4 time used in jazz and a great part of Cuban popular music, which also often uses a 2/4 time. In numbers like ‘Baila Mi Ritmo’ and ‘Anung Anunga’ the percussion section is particularly evident, serving as a frame for Oscar Valdes' vocal pyrotechnics. ‘Per Romper El Coco’ keeps more within the fifties tradition. In the

[Although the following insert notes by Luis Tamargo cover some of the same background provided by Leonardo Acosta, they are included in this feature because they cover the information about the group’s origins more succinctly and because they also contain some original thoughts and observations about IRAKERE’s music and its musicians.]

MISA NEGRA

© -Luis Tamargo, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“Most North American jazz aficionados didn't know anything about Cuba's jazz community until 1977, when the first U.S. tourist ship since 1961 steamed its way toward Havana. The port of departure was historically significant: New Orleans, the birthplace of jazz, where Jelly Roll Morton assimilated the tango habanero which he described as "Spanish tinge".

The comrades in Havana wanted the New York Yankees, but they got the greatest North American export instead. The tourist ship carried a significant load of jazz musicians, such as Dizzy Gillespie, Stan Getz, Earl "Fatha" Hines, and David Amram, in addition to various critics and producers. After all, Jazz has been doing ambassadorial duty (what Getz called ‘the jazz as diplomacy routine’) since the State Department sent Gillespie to Europe in the late 40's.

![]()

After checking out a Cuban group called IRAKERE at the Havana Libre (a hotel known in the pre-Castro era as - the Havana Hilton), U.S. critic Arnold Jay Smith described the band as ‘more musically exciting than any of the groups from which they have garnered their ideas.’ The 1977 seaborne jazz junket demonstrated to many U.S. jazz players that music in Cuba had remained as energetic and sparkling as in the pre-Castro years. Upon his return to the U.S., Gillespie announced that some inspiring Cuban musicians could out-blow even the most accomplished North American beboppers.

The curiosity and excitement generated by the jazz cruise was only a brief preview of what occurred when IRAKERE visited the U.S. in the summer of 1978, blowing the house down as a last minute addition to the Newport jazz Festival, after CBS and EGREM wrapped up one of the most complex contract negotiations in the history of the record business. Nevertheless, the promoters made a decision which turned out to be a major mistake: IRAKERE toured the U.S. with Stephen Stills because some greedy CBS executives believed that booking the Cubans as a rock group would add to their commercial appeal, particularly among the teeny hoppers.

It was the first time in nearly 20 years that a North American record company had signed a Cuban band, and CBS celebrated the occasion by investing $ 250,000 in a 3-day festival known as ‘Havana Jam,’ a gathering of prominent U.S. musicians (Weather Report, Dexter Gordon, Stan Getz, Hubert Laws, Bobby Hutcherson, Tony Williams, Willie Bobo, etc) and their Cuban counterparts. This 1979 exchange of musical ideology was conducted at the Teatro Carlos Marx (known in the Batista years as Teatro Chaplin), a 5000-seat theatre which looked unpleasantly like a North American department store, with Marx's signature spilled across the facade of the building in 10-foot high neon letters. Impressed with IRAKERE's performance at the ‘Havana Jam,’ Newsweek's Tony Schwartz referred to the band as ‘easily the most inventive of the Cuban groups.’

Coincidentally, while attending the "Havana jam", Fania Records' Jerry Massucci realized that his "salsa" empire was bound to collapse sooner or later, as he related to a Rolling Stone reporter that the Fania musicians had tried to copy the new sounds coming out of the island, without much success. The days of the New York imitators were numbered: When the Fania All Stars ("Latins from Manhattan", as Dexter Gordon called them) played at the Carlos Marx Theatre, the Cubans walked out in droves.

After winning the Latin Grammy Awards in 1979 and 1980 and recording two albums for CBS, IRAKERE's yanqui honeymoon was suddenly over. U.S.-Cuban relations went sour again, and IRAKERE was no longer able to record in the U.S. The band was then taped by Japanese engineers at Havana and Tokyo, and the resulting two albums were issued in the U.S. by Milestone in 1982 and 1983, without the promotional fanfare that accompanied the previous CBS releases.

The history of IRAKERE began, however, seven years before the ‘Havana Jam,’ when some of the members of the Orquesta Cubana de Musica Moderna, the best big band in the island, decided to form their own band. Chucho Valdés and Paquito D'Rivera were, from the beginning, the main firebrand of IRAKERE, although other original members of the group also came from the Orquesta Cubana de Musica Moderna. These flawless soloists realized that big band was not the best vehicle to renovate popular music, and decided to form an instrumental structure which could be adjustable to change.

IRAKERE had something refreshing to express in a style as profoundly rooted in Cuban music as in North American bebop. Thanks to IRAKERE, many U.S. jazz aficionados realized that Cuban musicians are neither out of touch with what's happening abroad nor easily slam-banged into Latin pigeonholes a la Desi Arnaz. IRAKERE's sound ranges seamlessly between acoustic and electronic music, combining incredible technique and wide conceptual enlightenment with ferocious groove tendencies. Despite the absence of the group's most improvising catalysts (Paquito D'Rivera and Arturo Sandoval, possibly the most important musical defectors of our times), IRAKERE remained on the cutting edge of Cuban jazz during the 80's, while maintaining its reputation as one of the most eclectic bands of the 20th Century, capable of moving spontaneously from traditional son to jabbing bebop to modern electronic riffing to elegant danzón to authentic Lucumi chants to Mozart and Beethoven, sometimes in the course of a single number.

![]()

The vigor of IRAKERE lies within each individual performer, and there are no weak loops in the band's musical chain. However, it is as a team, playing Chucho's volatile, changeable compositions that IRAKERE really stands out. The abovementioned facts can be appreciated in the CD "Black Mass", consisting mainly of original compositions which reflect Chucho's receptiveness to what's going on internationally, as well as his interest in renovating Cuban musical traditions. The title track, one of Chucho's most important compositions, is characterized by constant changes in time and atmosphere, a typical notion of Yoruba-derived music. Before IRAKERE, popular Cuban music utilized only the island's basic percussion instruments (tumbadora, bongos, pailas, güiro, etc). Besides these, IRAKERE incorporated instruments of Afro-Cuban rites, like the Batá drums and the chequere’. According to Cuban musicologist Leonardo Acosta, this percussive development "not only implies a new sound, but also a totally new way of conceiving the relationships between the intricate polyrhythmic passages, the phrasing of the improvisations and the actual dynamics of each piece". As illustrated in "Misa Negra", Jorge Alfonso (El Nino) was largely responsible for implementing the incorporation of complex and energetic Yoruba and Carabali rhythms into a musical context that once only responded to Congo and Dahomeyan elements. By the way, "Misa Negra" is probably the last recording that captured El Nino's powerful and innovative drumming which had a significant influence in the development of a new breed of U.S.-based Latin percussionists ("Mafiengulto"Hidalgo, Daniel Ponce, Luis Conte, etc). The four movements of "Misa Negra" properly describe the musical expressions of a Lucumi ceremony, as it is still practiced in Cuba: Prayer, approximation, arrival/development, and farewell.

![]()

On the other hand, the Brazilian flavor of "Samba para Enrique" is obviously dedicated to the ferocious Enrique Pla, a combination of Tony Williams and Billy Cobham who has maintained an unmistakable Cuban fire in his trap drumming. The other original composition, Chucho's "Concierto para metales", highlights the band's most amazing asset: IRAKERE's brass section, led by Coltrane-inspired Carlos Averhoff, ranks among the best in the world, and there is a mysterious agreement between the brass and percussion sections that allows them to spontaneously counterpoint each other. The last selection, Dave Brubeck's "The Duke", demonstrates how Duke Ellington's tremendous resources in thematic and orchestral invention have influenced the musical ideology of ChuchoValdes, leader and chief composer/arranger/conceptualist of IRAKERE. It Is public knowledge, by the way, that Ellington provided an occasional Cuban undertow to 1930's jazz through his early experiments with Puerto Rican trombonist Juan Tizol.

Last but not least, this recording clearly shows why the Cuban novelist and musicologist Alejo Carpentier stated once that Cuban popular music is "the only music that can be compared to jazz in the 20th century". It would be naive to assume that Cuba, the undisputed Mecca of Latin American music, is anything less than a hotbed of musical activity. And it's nice to know that we no longer have to endure a 3-day boat cruise to verify that Cuban jazz is alive and well, despite the geopolitical circumstances. This can be verified now through the Messidor catalog, which includes valuable recordings of the most prominent jazz artists from the Pearl of the Antilles.”

LUIS TAMARGO California, 1991

THE BEST OF IRAKERE [Columbia/Legacy CK 57719]

Although neither of the original 1979 Columbia LP’s - IRAKERE [JC 35655]and IRAKERE 2 [JC 36107] – have been released on compact disc in their entirety, we conclude this JazzProfiles feature on IRAKERE with Robin A. Vasquez’s insert notes from a CD compilation that does contain 10 of the original 13 tracks.

© -Robin A. Vasquez, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“Audiences fortunate enough to experience a live IRAKERE performance when the group exploded out of Cuba in the late 1970s witnessed the group's rapid ascension to the exalted realm of the musically extraordinary. During the all-too-brief period when they were still performing as a unit, IRAKERE earned its rightful place alongside American jazz geniuses Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, and other innovators and expanders of progressive musical horizons who heard something a little different and devoted their talent to the search for it.

IRAKERE pushed the jazz frontier deeper into the African heart of Cuba. Instead of using Cuban percussion patterns to enhance jazz compositions, they made their country's traditional music an equal partner or featured player in their work.

![]()

The members, Carlos del Puerto (bass), Carlos Emilio Morales (electric guitar), Jorge "El Nino" Alfonso (congas), Enrique Pla’ (drums), Oscar Valdés (vocals and percussion), Armando Cuervo (also on vocals and percussion), Jorge Varona (trumpet and flugelhorn), Arturo Sandoval (trumpet, flugelhorn, valve trombone and vocals), Paquito D'Rivera (soprano/baritone/alto sax), Carlos Averhoff (soprano/tenor sox, piccolo and flute), and Jesus Chucho Valdés (arranger, composer and all keyboards), were all formally trained, student of jazz, and world (lass soloists, (as Arturo Sandoval and Paquito D'Rivera, woodwind magicians, continue to demonstrate). Their contribution to the evolution of jazz as a gracious musical form that can accommodate and celebrate all cultures is rooted in the group's deliberate intent to cross-pollinate jazz instrumentation with traditional Cuban/African inspired music that weaved Batá drums (two sided Afro-Cuban drums associated with rituals instead of conga drums and timbales) and chekeres into their arrangements.

From a percussion perspective, it's still very polyrhythmic, but the layers often have an earthy, spiritual aura to them and the group's dense musical background allows them to leave few musical stones unturned.

![]()

The vibrant "Gira Gira" showcases the interplay between drum set, congas, and chekere using a Congo rhythm with Chucho on Fender Rhodes, the keyboard instrument of choice for Herbie Hancock and other progressive jazz musicians during that period. There's a smooth segue into a bass guitar and bass drum driven disco downbeat, a steady cadence that pauses for a sorrowful flute phrase bathed in distortion to give it almost a rock sound and a bluesy guitar riff. The song is lively and complex but also political With its message about workers whose suffering in obeying the commands of the foreman or overseer echoes the pain of their slave ancestors. In that context, the drum/bass beat embodies the sound of a long march, the forced footsteps of workers being led into an endless day of pain, toil, and indignity, the flute and guitar solos sound like a lament, a momentary, solitary wail

in the wilderness.

It's got a good beat and you can dance to it, but the full power in this modern day ode to mistreated workers lies in its connection to a historical necessity to hide or take refuge inside the music of one's homeland.

American slave owners prohibited the use of African dialects among their slaves, often punishing them severely for practicing traditional musical rituals honoring births, deaths, marriages, etc. Drumming in particular was deemed as subversive with its potential for communicating in yet another language the slave owner did not understand, but where the drumming, (often achieved with spoons, wooden boxes, beating on porch rails or anything handy) was allowed to follow, particularly in Cuba, it become the heartbeat, the pulse, the unifying force of a strong willed people who set their music free in a hostile land even while they lived in bondage.

Having imported their own musical heritage through dance and the voice of stringed instruments (the forerunners of today's guitar), Spanish slave masters in Cuba were more tolerant of the African passion for drumming. (Their influence was enduring-there's a Spanish high-society danzón feel to "Ciento Años De Juventud" included in this collection, but it starts with a Fats Domino/Jerry Lee Lewis kind of piano tinkling.) Under the guise of celebrating sacred Catholic rites, slaves in Cuba were able to preserve their Yoruba language and music and honor its African deities, or orishas. Music became the Cuban slaves' weapon of resistance and a barrier against complete assimilation, eventually infiltrating the fabric of village life all over the island.

It was the merging of what was available at the time to a musical people: the intricate patterns of Spanish stringed instruments and the propulsive, rhythmic, multi-layered drum/dance/voice triad of African celebratory or religious music, that formed the foundation for Afro-Cuban jazz.

Though separated by language and geography (and ultimately politics), there have always been jazz musicians in Cuba who played as well as anyone anywhere and admirers on both sides of the water. Years before the embargo, Swing Era big band leaders borrowed heavily from Cuban musicians who migrated to New York. American audiences easily accepted contemporary Afro-Cuban dances, La Rhumba, La Cha Cha Cha, La Congo, and El Mambo, embracing Desi Arnaz as a musician more readily than as the husband of its beloved Lucy.

Through their collaborations (depending on who you talk to), Dizzy Gillespie, Chano Pozo, Charlie Parker, Stan Kenton, Machito, and Mario Bauzá are credited with contributing a hybrid strain to that genre, and naming their offspring Cu-Bop. They left the ground fertile for a new Afro/Cuban/American musical discovery.

But until IRAKERE's successful experiments with blending both traditional jazz and traditionally Cuban elements and the political maneuvering that one assumes had to take place allowing the group to bring it off the island during the Cuban embargo-they were the first Castro-era group to record and tour abroad – the merge was incomplete.

The group's finesse in calling all historical and musical forces into play (along with theinspiración style of improvisational singing) gave them a potent arsenal from which to create. No song is without several well conceived and interestingly placed influences, particularly the three movements of the 17-plus-minutes-long "Misa Negra (The Black Mass)" which stretches across a galaxy of sound using chimes, cymbals, bird whistles, a haunting background vocal melody, call and response singing. Almost a suite but definitely a masterpiece of composing and arranging, "Misa Negra" establishes a cosmic aura, featuring Chucho's brilliant keyboard strategy, and breakneck arranging for the brass section. Tempo and mood change along the way.

Introduced by cowbell, the song "Ilya" demonstrates the power of call and response not only between the primary vocalist and background vocalists but among the singers and drummers. Pushed by a 6/8 rhythm into a religious/Yoruba direction, the chorus (or coro) inspires the singer in a kind of intense conversation with each "speaker" responding to the passion of the others. (Sandoval shines in this selection named after one of the bata drums.)

Unless the planets align themselves again to produce a reunion of these exemplary musicians, fans of their music can only experience IRAKERE through old records, IRAKERE, IRAKERE 2, the Havana Jam LPs, etc. But the advances in recording technology since the group disbanded present old fans and new audiences with the chance to hear them on CD which provides this music with the sound quality it so richly deserves.”