© -Steven Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

"In 1944-1945 I was in the service stationed outside Philadelphia. I used to go to this little night club in town located in an alley named Ransted Street (true). It was owned by a wonderful jazz clarinet player named Billy Kretchmer. I used to sit in occasionally and one day Billy introduced me to a tall skinny, lanky kid and told me that that kid was a terrific guitar player!! Coming from Kretchmer, that really sank in.

In 1946 I joined the staff at NBC in NYC. It was around that time that I met guitarist Sal Salvadorand Sal introduced me to this tall, lanky roommate, Tal Farlow. I used to go up to their apartment and hang out and that's when I first heard Tal play and I remembered what Kretchmer had said about the tall lanky kid... Kretchmer had understated Tal!!

Not too long after that, Tal became part of the Red Norvo Trio and the rest is history. The trio was playing in a swanky East Sidenight club called The Embers. A fellow guitar player and I went to hear Tal and this guitar player said to me, "No wonder he can play so good, look at those long skinny fingers !" Well, I thought for a few moments and I said, ‘No, that's not right... Segoviahad fat fingers and Django could only use two on his left hand.’ I said, ‘That kind of playing doesn't come from the fingers, that kind of playing comes from the heart and soul.’

GOD never put a nicer soul on this planet than my very dear friend Tal Farlow."

-Guitarist Johnny Smith, as told to fellow-Guitarist Howard Alden, April 2004

Not that I'm anywhere in his league, but recently, for whatever reason, I've become very mindful of this quasi-admonition by Gene Lees highlighted in the following quotation:

"In the past few years, I have been only too aware that primary sources of jazz history, and popular-music history, are being lost to us. The great masters, the men who were there, are slowly leaving us. I do not know who said, "Whenever anyone dies, a library burns." But it is true: almost anyone's experience is worth recording, even that of the most "ordinary" person. For the great unknown terrain of human history is not what the kings and famous men did — for much, though by no means all, of this was recorded, no matter how imperfectly — but how the "common" people lived. When Leonard Feather first came to the United States from England in the late 1930s, he was able to know most of his musical heroes, including Louis Armstrong and Jelly Roll Morton. By the end of the 1940s, Leonard knew everybody of significance in jazz from the founding figures to the young iconoclasts. And when I became actively involved in the jazz world in 1959, as editor of Down Beat, most of them were still there. I met most of them, and became friends with many, especially the young Turks more or less of my own age. I have lived to see them grow old (and sometimes not grow old), and die, their voices stilled forever. And so, in recent years, I have felt impelled to do what I can to get their memories down before they are lost, leading me to write what I think of as mini-biographies of these people. This has been the central task of the Jazzletter."

By way of background, I recently put out a call for help to some of my Jazz buddies for information regarding guitarist, Tal Farlow.

The response was so overwhelming that I decided to keep it all in one place and prepared this lengthy feature about Tal Farlow with “the help of my friends.”

In other words, to do as Gene Leessuggests and prepare a mini-biography of Tal by doing a [non-exhaustive] “research of the literature.”

Whenever I think of guitarist Tal Farlow I think of fast notes flying all over the place. Maybe it because as Doug Ramsey comments in his book, Jazz Matters:

“Part of the fascination with Farlow’s playing is that he plays close to the edge of time.”

I gather that the development of Tal’s speed on the instrument begins with one of those “necessity-is-the-Mother-of-invention” stories.

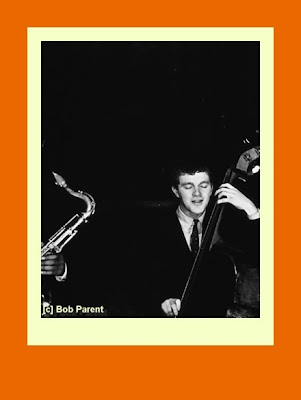

Tal always claimed that he worked to acquire speed in his playing to keep up with the speedy vibraphone playing of Red Norvo, whose trio he was a member of in the early 1950’s along with the legendary bassist, Charlie Mingus.

According to Ted Gioia in West Coast Jazz: “… Norvo had a preference for fast tempos” which initially created misgiving in bassist Charlie Mingus and Farlow who recalled: “I had all kinds of difficulties at first.”

Ted goes on to observe:

“The recordings of the Red Norvo Trio tell a different story from these mutual laments about musical inadequacy. The ensemble work bristles with virtuosity; few trios of that period, perhaps only Art Tatum's or Bud Powell's, could boast as firm a command of fast tempos. Mingus emerges on these sides as a powerful young bassist with solid time and a strong, resounding tone. His solos are few, but his presence is constantly felt.

![]()

Farlow is perhaps best known as a consummate bebop guitarist: ‘In terms of guitar prowess,’ writes critic Stuart Nicholson about these sessions, ‘it was the equivalent of Roger Bannister breaking the four minute mile.’22 But on these recordings his speedy melodic inventiveness is matched by an extraordinary variety of rhythmic and harmonic variations. On Cheek to Cheekhis elaborate chord substitutions hint at the polytonal work of the avant-garde. On Night and Day he pushes the group by playing the guitar body like a bongo. In essence, Farlow serves as soloist, accompanist, and rhythm guitarist—all with great skill. Freed by the absence of keyboard and drums, Farlow continually takes chances with the music.” [p. 341]

The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz offers this description of Tal’s playing:

“Farlow was a leading guitarist in the early bop style, with phenomenally fast execution (…) and a rapid flow of ideas. He has been admired for the unusual intervals in his improvised lines, his original handling of artificial harmonics, and his gentle touch (even at exceedingly fast tempos), achieved partly by using his thumb instead of a plectrum.” [J. Bradford Robinson]

Although he’s rarely mentioned with the legendary Bebop masters who brought superior techniques to super fast tempos – musicians such as Charlie Parker on alto saxophone, Dizzy Gillespie on trumpet, J.J. Johnson on trombone and Bud Powell on piano – Tal brought speedy, scintillating Bebop ideas to the amplified guitar and in so doing, transformed the instrument, a process that had begun a decade earlier with Charlie Christian.

Tal’s relative, but since remedied, obscurity is also a point that is also touched on by Richard Cook and Brian Morton in The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD, 6thEd.:

“One could hardly tell from the catalogue that Farlow is one of the major jazz guitarists, since most of his records - as both leader and sideman - are currently out of print. Perhaps, in the age of Bill Frisell and Pat Metheny, his plain-speaking is simply out of favor.

His reticence as a performer belied his breathtaking speed, melodic inventiveness and pleasingly gentle touch as a bop-orientated improviser.

His tenure at Verve included some marvelous sessions and at least The Swinging Guitar Of Tal Farlow [Verve CD 314 559 515-2] has returned; there are plenty more that could be reinstated in the catalogue. [Actually, since this writing, thanks to Michael Cuscuna and his great team at Mosaic Records, all of Tal’s Verve CD’s were subsequently issued as a limited edition boxed-set.]

Farlow's virtuosity and the quality of his thinking, even at top speed, have remained marvels to more than one generation of guitarists, and given the instrument's current popularity in jazz, his neglect is mystifying.”

The Jazz Masters [#41 Verve CD 314 527 365-2] compilation remains an excellent introduction to his work, creaming off the pick of seven albums at Verve.”

Each of Tal’s Verve CD’s have also been individually issued to CD by Verve and the editorial staff at JazzProfiles thought it might be interesting to continue its remembrance of Tal and his music by exploring the insert notes to a few of them on these pages.

“Of all the guitarists to emerge in the first generation after Charlie Christian, Tal Farlow, more than any other, has been able to move beyond the rhythmic, melodic, and harmonic vocabulary associated with the early electric guitar master.

Tal's incredible speed, long, weaving lines, rhythmic excitement, highly developed harmonic sense, and enormous reach (both physical and musical) have enabled him to create a style that clearly stands apart from the rest.

He was the first jazz guitarist to explore and incorporate the total instrument. Players as stylistically diverse as Jim Hall, Steve Howe, Alvin Lee, John Mclaughlin, Jimmy Raney, and Attila Zoller have all acknowledged Tal's influence on their guitar playing and, in some cases, on their outlook on life.

Talmage Holt Farlow was born on June 7, 1921 in Greensboro, North Carolina. He was raised in a musical family. His mother played piano and his father played several instruments including guitar, violin, and mandolin. His father gave him a mandolin that was retuned like a ukulele and showed him a few basic chords; he left Tal to figure out the rest. Music was considered a hobby in the family so Tal's first vocation was that of sign painter. (Until a few years ago, he made a good living by painting signs whenever the opportunity arose.) As Tal continued to develop musically, he also picked up his father's interest in electronics and often spent time building radios and other types of equipment. Eventually, after hearing Christian's sound, Tal built an electric guitar by constructing a pickup from an old pair of earphones and a coil of wire.

At age twenty-two and playing professionally, Tal attracted the attention of bandleader Dardanelle Breckenridge. Between 1943 and 1945, Tal toured with Dardanelle up and down the East Coast, playing in such cities as Richmond, Virginia, Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia and eventually landing at the Copa Lounge in New York City. Upon leaving Dardanelle he returned to Philadelphia, splitting his time between painting signs and playing with a clarinetist named Billy Krechmer at a jazz club called Jam Session.

![]()

In 1948 Tal, along with pianist Jimmy Lyon and bassist Lenny DeFranco (brother of clarinetist Buddy), left Philadelphia and returned to New York City. Within about six months, the guitarist landed a gig with a popular cocktail pianist, Marshall Grant. It was during an engagement with the Marshall Grant Trio at Billy Reed's Little Club that bandleader Red Norvo first heard Tal. Soon after, the vibraphonist hired him to replace Mundell Lowe. The re-formed Red Norvo Trio, with Red Kelly on bass, headed to California and then to Hawaii for a six-week engagement.

The trio returned to California to play at The Haig, and it was there that Norman Granz first heard Tal and immediately approached him to offer a recording contract. (Of the more than thirty albums in Tal's discography, nearly one third were recorded for Verve between 1952 and 1960.) Although Tal was given a lot of artistic freedom, ‘Norman liked some things more than others. From me, he liked fast tempos,’ the guitarist relates.

All of the characteristics of Tal's unique style — the intricate single lines, the complex re-harmonization’s and chord voicings, the special effects such as harmonics (both single-line and palm), and the retuned A string (for extending the bass range on chord solos) — are found on these tracks. …

Of all the words used to describe Tal Farlow, the one most often used is genius. When I asked him how he felt about the term, he displayed his characteristic grace and humility, then absolutely rejected it. I proposed that his successes were, like those of so many other greats, a result of hard work and really digging it out. His reaction to that assessment was,

‘That seldom ever entered into any particular instance of my picking up the guitar and practicing in any conventional or traditional way. I mean, I would hear something that I liked from Bud Powell or Bird and try to work it out and gradually put it into my little bag of tricks.

‘I think about Jimmy Raney's attitude toward the guitar, and mine is similar, in that I don't have any great, strong allegiance to the instrument. Jimmy said, 'It happens to be the instrument I can play.' It's less a love for the instrument than it is a love for the music.’”

Steve Rochinski - December 1994

Steve Rochinski is a guitarist, on the faculty at the Berklee College of Music in Boston, and the author of The Jazz Style of Tal Farlow: The Elements of Bebop Guitar (Hal Leonard, Milwaukee. 1994).

Bill Simon provided these insights and observations about Tal and his music in these insert notes to The Swinging Guitar of Tal Farlow [Verve 314 559 515-2]:

“Ask any professional guitarist — in jazz, that is — to name his own favorite guitarists and it's ten to one he'll name, in this order, Segovia, Charlie Christian, and Tal Farlow . . . Segovia for his complete mastery of the instrument and his consummate musical artistry, the late Christian for his powerful jazz drive and for his original concept of the guitar's role in jazz . . . and Farlow as the currently operating individual who has carried the instrument to its most advanced and satisfying stage in modern jazz.

Guitarists comprise a well-knit clique these days. As a group, they probably are more familiar with the background of their instrument than is any other group of musicians. Also, they are the most versatile. Some of our best jazz guitarists started out as hillbillies and as blues strummers. The modern guitarist can play anything from a Bach suite to plain old country "chording". He can play flamenco, smart show tunes, can riff like a sax section in a jazz band, and can whisper intimate accompaniment to a torch singer.

It seems that the top men are constantly in touch with each other, tossing "gigs" to each other, exchanging ideas, and the like. I've never seen it the same way among other types of instrumentalists. In fact, it was Mundell Lowe, another of the top guitarists and one of the most successful, who recommended Tal as his successor when he left the Red Norvo Trio. Most of the top-rank modern guitarists have played with Red, and his group always has been the showcase wherein their talents have been viewed by the larger jazz public. …”

The reissue of This Is Tal Farlow as a limited edition Verve Elite CD [314 537 746-2] offered this introduction:

“By the time Tal Farlow came to New York, he remembers in the interview that comprises the liner note, a lot of musicians knew of his remarkable technique. His prowess had been developed in what he calls ‘cocktail trios’ — nothing rowdy, he says, so he could ‘get away with a lot of stuff.’ And of course in New York he became mesmerized by the great beboppers and got into more complex harmonies and new ways of phrasing.

This union, of technique and concept, produced records now recognized as landmarks in the development of the guitar trio.

Idolized by Wes Montgomery, Farlow is the guitarists' guitar player; this is the album that best displays his unique talent.”

Here’s the interview with Tal Farlow conducted by Barry Feldman in March, 1997, about a year before Tal passed away:

Reissuing This Is Tal Farlow

“BF: How did you end up being a guitar player, being from the South and not liking country music?

TF: Country music never appealed to me very much; I preferred what I was hearing over the radio, the standards, which is what was being played those days.

BF: Right, it was the big bands. I think there's an assumption that anybody from down there is going to listen to country music, so how did you — ?

TF: Well, there was a lot of that around, you know, that was the music, that people in the neighborhood were into.

BF: Did you like listening to Bob Wills?

TF: Well, he had sort of a foot in each camp. I mean, he had a couple of jazz—

BF: —fiddlers.

TF: The guitar players, too; I think [they played jazz]. They were improvising, and I was digging that, they were really good players.

BF: I think Jimmy Wiebel played with him. I know there was a famous song, Roly Poly, and Jimmy played a famous solo there. I know he got out of that and played more straight jazz. But you're appealing more to the rhythm section — when you say rhythm section, you're referring to hearing Count Basie.

TF: Yes, the music of the horns and the drums. I didn't know at the beginning that there was any special kind of music that jazz guys were playing. I mean, I was hearing dance music generally.

But the more I learned about what the big bands were doing, the more I dug Basie and Ellington. And then there were Guy Lombardo and Freddy Martin, the sweet type, arranged music with [just] melody [while] the other guys played loose with more spirit.

BF: And the drive.

TF: Right.

BF: Did you ever play Freddie Greene's type, four-to-the-bar rhythm?

TF: No, I spent very little time in any kind of rhythm section, actually. I've played mostly in really small groups, where rarely if ever did I play four to the bar.

BF: Now the phenomenal technique — which came first, the technique or hearing Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie and going, "Oh, boy, I gotta play faster"?

TF: Well, I couldn't play fast until I got with Red Norvo [in 1949] because there was never ever a demand for it.

BF: Really?

TF: You know, I was not in groups that were — I was a professional before I was a jazz player, because I played quite a long time with Dardanella. She was a great musician, a great piano player, but she was into playing at the Copacabana, places like that. She liked jazz, too, and we played a little bit of that.

I got to New York in a roundabout way, because I went to Philadelphia first. I used to go from my sign-painting business in North Carolina when a gig opened up in Philly — my friends would call me and I would go there and play.

The town was full of, I think they call them cocktail trios. This was during the war, and the clubs had to charge [an entertainment] tax, add it to the customer's bill, if it had dancing or singing. So in most places there was only instrumental music, and the guitar was very popular then — it could be paired with an accordion or vibes or piano. And then with a bass you had your typical cocktail trio.

They were all listenable; it wasn't rowdy or anything. So you could get away with a lot of stuff: It didn't insult anybody. There was quite a lot of that work around Philly. And also in those days there were a lot of big bands coming through town, and those guys would come to the clubs where I was playing. They'd hear me, so by the time I got to New York quite a lot of people — musicians — already knew me.

I used to hang out with Jimmy Raney quite a bit. And we used to just sit in a room and play a lot. We were both big fans of Bud Powell, because we both figured, Boy, if what he was playing could come out of a guitar amplifier...

BF: Why Bud and not Bird or Dizzy?

TF: Well, there's a similarity between the sound of the guitar and the sound of the piano. It's a percussive sound, and that was one of Bud's big features. Buddy DeFranco said it sounded like Bud's fingers were going three inches into the keyboard when he played: He was playing with such fire. Also, he played real long phrases, predominantly eighth notes.

BF: That's what struck me when I first heard how you play, without skipping a beat, at fast tempos. Because your strong tone ... I never heard guitar like that before.

When I heard your recordings, it completely blew my mind that you could just step in with the horn players without missing a beat. The other guitar players — I'm not criticizing them — sometimes didn't, they just didn't. I read an interview of Wes Montgomery, and he said that when you came out, he hadn't heard anything like it: the ability to hang in the pocket with all those horn players.

TF: I was fascinated with Bird and Diz, getting into more complex harmonies, with different ways of phrasing and different sounds from the rhythm section. I tried to copy some of Bird's stuff, as everybody knows... as everybody did. But I didn't really have much opportunity to play [that] until I got with Red Norvo, when I replaced Mundell Lowe.

Before that I had been working with a piano player named Marshall Grant, who was not like Dardanella but more in that camp than jazz. I learned a lot of Broadway show tunes from him. Some were obscure, and I suggested to Red that we play them; he knew some of them, too. This was before that was a big thing, making—

BF: — playing the standard straight up, yes, they used to put—

TF: — "My Fair Lady" and things like that. I guess the things that I played with Red, a lot of those things just evolved on the job — because we worked pretty steadily, we worked a lot of restaurants in Hollywood and New York, too.

Recording for Verve

BF: You had done a lot of recording with Eddie Costa, but This Is Tal Farlow has a drummer present. And Eddie was a wild man, a great, driving player. He's really not very well known now.

TF: No, he died too early.

When I was out on the Coast with Red I got a message from a guy named Sy Barren, who owned the Composer Club. A lot of guys I knew had been working for him; they probably said, "Why don't you try to get Tal?" Eddie was one of those guys, although I didn't know him, but I did know Vinnie Burke, who was the

third guy in the trio as it first started. We had played there quite a lot, maybe two weeks at a stretch, and he'd have us back maybe three times a year. So, [we started] out, Vinnie Burke, Eddie, and me. Later on it was Bill Takas and Jimmy Campbell.

Jimmy was playing with Marian McPartland, and sometimes he would play with our set, because we didn't have drums. And sometimes Bill Evans, who was a good friend of Eddie's, came in and played piano and Eddie would play vibes. BF: I think what was great about it, with Eddie and you, was the pushing.

TF: We had that going for us. We sort of egged each other on.

BF: It was tremendous egging on, because it made great music. And Eddie would play a lot of those octave solos, the double-octave solos they play way down, low in the bass range of the keyboard. And you'd follow them. The trio records are amazing, but this one is special because you know you have a drummer there. I figured that was the kicker, because we didn't get to hear you guys play much on record with a drummer.

TF: I remember that Bill Takas was supposed to make the record because he'd been playing with us. He said he would be there but he was hung up at the airport, it was a snowstorm or something. And Knobby Totah, I think he was recording with Cy Coleman somewhere in the same building. He had also been playing with Marian at the Composer, and he knew the stuff that we were playing. You know, you don't really have to know it that well —

BF: Yes, it's pretty much standards.

TF: And on some of it, it's hard to tell who's playing what.

BF: You did the record where you wrote the arrangements, The Portrait of Tal Farlow. Did you want to do more records like that, but Norman [Granz] didn't want you to?

TF: He didn't care really what I did. He was less interested in me trying to see if I could write and have a bunch of horns. He really wanted me to play almost all the time; he said it's you the people [want.] He put your name on the album, that's who they want to hear. He said you bring all these other guys.... But I think Jimmy had been doing things like that, with a couple of horns. So I just got the idea, trying to write some things out. I didn't write endings, and it's hard to put them together on the date.

BF: It seems Norman stood by you a long time.

TF: Well, he had the people that recorded for him, and then he had the guys that worked for him. I never did work for him other than making records, you know. But I guess he used guys like Ray Brown — I would get him whenever I could.

BF: When you used the drummer, that was your call?

TF: Yes, I think so. Though Norman may have asked for him.

BF: Norman ran the most successful jazz operation from a financial standpoint. There was nothing to compare to what Norman Granz pulled off.

TF: Yes, I know.

BF: Did he ever ask you to go out with JATP?

TF: No.

BF: Would you have gone if asked?

TF: I might have, but when I met him he didn't say...Well, he knew I was working with Red, we were working steady. But I don't think I would, I think I was more in his view a recording guy than—

BF: Yes, he usually had Herb Ellis and Barney Kessel.

TF: I think Barney was a very close personal friend of Norman's. [They were friends] before Norman really hit it big.

BF: So you did most of your recordings for Verve out in LA, is that correct?

TF: Yes, most of them.

BF: Now, you finally, you retired around 1959.

TF: Well, I didn't retire, but I came down here in Jerseyand, you know, things were sort of slow then, and...

BF: Are you asthmatic?

TF: No, I used to be when I was kid.

BF: I read that that was the reason you didn't want to be in clubs.

TF: Oh! I think a guy in Germany [started this]___

BF: You're killing all my stories, "Tal Farlow Quits the Clubs Because of Asthma".

(Laughter)

BF: There's not a lot to like, I guess, about being on the road after fifteen years, playing in the clubs.

TF: Well, I like to do festivals, and occasionally I'll work in a club.

Here are some excerpts from Nat Hentoff’s original liner notes to the LP version of The Swinging Guitar of Tal Farlow:

“‘Of all current jazz guitarists,’ Jimmy Raney was saying recently, ‘Tal is the one I most like to hear. There are several with a great deal of facility and others with less facility but more ideas. Tal has both. He also does the best chord work of anyone I've heard. I mean in terms of its polish. He has a wild harmonic sense, and fortunately, the long fingers to match it.’

‘His time and sound are fine,’ Raney adds, ‘and I'm especially impressed by the fact that when he plays a solo, he's never unsure and never hung up. It's not that he's worked out a bag of tricks — because he really does improvise — but that he knows what he's doing and is in complete control all the time.’

Tal himself, during a Metronome interview, stressed the importance to him of sound. ‘If I don't get a good sound, I can't play at all. A good sound to me is a natural sound, a natural guitar sound. I play a good many fast tempos, because I feel better playing in that kind of groove. I don't really like the sound I get on slow tempos or ballads. It's thin. It's difficult to sustain a note on the amplified guitar, especially in the high register. Johnny Smith gets a beautiful sustained sound; he does it by adjusting the amplifier a particular way.’

Raney feels — and I agree — that Tal's tone is hardly that attenuated on ballads and that his conception on slow tempos is considerably more absorbing than that of most of his contemporaries. And at whatever tempo, there is a resilient, forward-motion pulsation that can be exhilarating when Tal is playing with men of his caliber and with conceptions that complement his. …

Tal ended the conversation for these notes by citing the guitarists he most admires — Jimmy Raney, Barney Kessel, and Jim Hall. ‘And what Johnny Smith can do with sounds. He can sustain long notes and his sound is almost as strong whenever he stops a note as it is when he starts it.’”

Tal has been the subject of three articles in Downbeat Magazine. The first of these was in the December 5, 1963 issue and it was contributed by Ira Gitler:

“Whatever Happened to Tal Farlow?”

“It was a hot and hectic day in July when it happened. The Down Beat editorial staff was assembled in a Chicago hotel to cover a music-merchants convention being held there, when a representative o! the Gibson guitar company casually mentioned to one of the stall members that there was a concert given by the company to introduce some ot its new instruments, one of which was going to be a Tal Farlow model.

‘Tal Farlow,’ the staff man said, mulling the name of one ot the great Jazz guitarists who had not been heard on the Jazz scene for five years. ‘Whatever happened to him anyway?’

‘Why don't you ask him?’ replied the company representative. ‘He's coming in this afternoon.’

Alter the initial shock had worn off, the staff man set up an appointment to interview the guitarist in the short time between Farlow's rehearsal and performance. But conventions being what they are, there was no opportunity to get into a lengthy discussion with Farlow. A promise of another get-together in New York was agreed upon.

Last month in New York. Farlow was more relaxed and voluble than he had been in Chicago. He had driven up from his Sea Bright, N. J., home on the Atlantic coast, where he has lived since his marriage in 1958. That year also had marked his last important public appearance, at the old Composer club on Manhattan's W. 5Sth St., with the late pianist Eddie Costa and bassist Vinnie Burke.

Farlow had been voted new-star guitarist in the 1954 Down Beat International Jazz Critics Poll, won a similar award in a poll of musicians conducted for the 1956 year book edition of Leonard Feather's Encyclopedia of Jazz, and had taken first place in the "established" division of the 1956 and 1957 critics polls. Yet. with all this recognition, he had chosen to remove himself from the scene.

Farlow. a shy, yet warm, person whose appearance has accurately been described as Lincolnesque, said of his attitude toward seeking jobs in music, ‘I don't push very hard.’ Perhaps even more telling is his statement; ‘I never really have thought of myself as a 100% percent professional musician. There were times when I would stop and do sign painting.’

In Greensboro, N. C., where Talmadge Holt Farlow wasas born in 1921. he worked in a sign shop when he was about twenty years old.

His father played guitar, mandolin, violin, and ‘even some clarinet.’ Tal had started playing guitar, too. but it was mostly ‘sort of North Carolina style until I heard Charlie Christian,’ he explained. ‘These fellows had a music store opposite the sign shop, and I used to go over there and wear out the records. I didn't have a player of my own.’

Farlow did have a radio though, and he heard Christian on remote broadcasts- of the Benny Goodman Band.

‘They'd let him stretch out and give him a whole fistful of choruses.’ Farlow reminisced. ‘First, I couldn't figure out what kind of instrument it was. It was a guitar of some kind, but at that time electric guitars were mostly all Hawaiian guitars. It had a little of that quality, but it not that slippin' and slidin’ business of a Hawaiian guitar. That was the first time I had heard an electric Spanish guitar."

As he did with countless other guitarists, Christian soon had exerted a tremendous influence on Farlow. ‘I copied his choruses—I learned how to play them,’ Farlow said. ‘Then I started listening to other Jazz groups. One of them was Count Basic's little band with Lester Young, and I found out there was a lot of similarity between some of the things Charlie was playing and some of the things Lester was playing. Also, Lester's style was pretty easily adapted to the guitar. It sort of fell in place.’

Farlow didn't limit his listening to records and radio. Through his first profession he was able to hear live music. He explained: ‘They had these dances for colored only, and white people couldn't get in except for an area reserved for spectators. I did all the signs for these dances so I could get a couple of passes - heard Hampton, Basie, Andy Kirk. The Trenier twins had a band that sounded like Jimmie Lunceford's. I think Lunceford played there too. I heard a lot of good music that way. Except that I know that a lot of the fellows we'd read about in Down Beat like - Lester - he'd never be in the band down there because he had other places to be when the band made the southern scene, I guess, I did meet guitarist Irving Ashby when he was with Hampton.’

During the war Farlow started playing with dance bands around Greensboro. Pianist Jimmy Lyon, who in later years was a fixture at the Blue Angel and who recently has been holding forth at New York's Playboy Club, was stationed at a nearby air base, and he and Farlow began playing together. ‘He has a magnificent harmonic sense,’ Farlow said. ‘It stimulated my interest.’

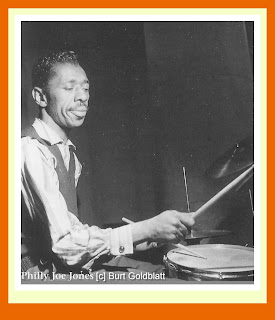

![]()

Farlow is that rare bird—the natural musician who never took lessons and who still can't read. ‘I never did study because I don't think there was anybody in that area who could have given me what I was alter.’ he said. ‘You should learn to read right away, With guitar, it's easy to play a little bit. and alter you've played that much, you get to the point where it's boring to go back and learn scales and read. Even now I sit down and say “I’m going to brush up and see if I can't make my reading passable anyway.” You can just take so much of that and you start pla\mg something else.' He added that his reading lack makes him ineligible for studio and recording work of a certain nature, but when asked it he would like to play these jobs, he smiled and replied. ‘I don't believe so.’

In 1942, Farlow went north to Philadelphia but soon returned to Greensboro and sign painting. After the war he returned to the QuakerCity where he joined the trio of vibist Dardanelle. After playing in Philadelphia, the group moved to the Copa Lounge in New York. Charlie Parker was playing on 52nd St., and whenever Tal was off he would head right for The Street.

Farlow recalled. ‘Every Monday I would get up there before anyone else and hope Bird would show, which he sometimes did, sometimes didn't.’ Of bebop, Farlow said, ‘That was the only thing for me then. It seemed to me that they were making a new start. Although I hadn't been listening real close for a few years, it seemed so new and so much different from what was going on before.’

He did no jamming: he just listened. ‘As Herbie Ellis would say, “‘I wasn't going out in that deep water.'”

Farlow then moved back to Philadelphia and worked at clarinetist BilK Krechmer's club in a trio that included the owner and pianist Freddie Thompson.

Since the group used no bassist, Farlow would play the bass line on guitar. ‘Sometimes a drummer would sit in on snare.’ the guitarist said. "Krechmer's was right around the corner from the Click Theater-Restaurant on Market St., where Goodman. etc., used to play. Guy’s used to duck down on their intermission and sit in with us.’

With Jimnn Lyon and bassist Lenny DeFranco (clarinetist Buddy DeFranco's brother), Farlow came back to New York. The three intended to get their Local 802 cards and form a trio. During the first three months of waiting out his 802 membership, the applicant musician is permitted to work only one-night engagements. Lyon and DeFranco got their share, but not Farlow.

‘Piano and bass are marketable in the club-date field,’ he said, ‘but they didn't care for a guitarist who couldn't read or, more than that, couldn't sing.’

Alter working for a New Yorksign shop. Farlow took Mundell Lowe's place in vibist Margie Hyams’ group at the Three Deuces. "We were working opposite Charlie Parker there for two or three weeks he recalled. ‘I got to listen to him quite a bit at close range.’

A Southampton society job with leader Marshall Grant followed. ‘By the time we [Lyon and DeFranco] got our second three months in, we were scattered all over,’ Farlow said. ‘We never got together.’

Farlow did play with Buddy DeFranco, in a group that included Milt Jackson on vibes and John Levy, the bassist who is now active as a personal manager. This occurred in 1949. when Farlow was living on W. 93rd St. with fellow guitarists Jimmy Raney and Sal Salvador and alto saxophonist Phil Woods.

‘Sal’s father had a store in Massachusetts.’ Farlow recalled, ‘and every so often he would send down a big cardboard carton lull of canned goods and things. That was for Sal, but everybody partook -The CARE package we called it.

‘Jimmy and I played a lot together. Sal. too. but he was on the road a lot. Jimmy and I were racing for last place when it came to work.’

Farlow’s work shortage was solved at the end of the year when he became part of the Red Norvo Trio. Almost immediately he went to California with the veteran vibist. ‘And alter working so hard to get a New York card,’ the guitarist said.

‘Working with Norvo, he said, helped him develop speed and facility:

‘Red liked to—I guess he still does—play real fast tunes, things on which he was featured with Woody Herman’s band, like I Surrender Dear and The Man I Love. When I first went with him, it was, embarrassing because I couldn't keep up with him. and it was a question of its having to be done. I worked on my technique so I could make the tempos.’

Red Kelly was the bassist with the group, but he left to rejoin Charlie Barnet and Charlie Mingus took his place. Farlow said. ‘I think Mingus was carrying mail in San Francisco at the time. Red knew him, called him, and he came down.’ Together, the trio developed a tremendous unity, as their old Discovery records still attest.

Farlow left Norvo in 1954 to work with Artie Shaw's reactivated Gramercy Five but returned to Norvo for a while before leaving permanently in 1955. By this time he had established himself as one of the ranking guitarists of Jazz: his fluidity, fire, amazing continuity. and purity of sound were the hallmarks of his style.

Farlow was in California in 1955 when Sy Barron, owner of the Composer, contacted him and persuaded him to come back to New York to play at the club in a trio with pianist Eddie Costa and bassist Vinnie Burke.

‘Eddie had given him the idea.’ Farlow said. ‘I hadn't known Eddie, but he was a friend of Sal's [Salvador, Eddie and Vinnie had been playing at the Composer in a two-piano group with John Mehegan.’

This was the beginning of a happy association for both players and club. When the Composer closed, Farlow lost a home. He hasn't played in a club since, except for some sitting in with Burke at the bassist's job in Long Branch, N.J.. last summer.

Barron. however, is in the process of erecting a new club, the Composer-Lyricist, on W. 56th St., and he wants Farlow to open it for him sometime in December—if everything goes according to schedule.

In the meantime. Farlow has not neglected his playing completely. Periodically, fellow guitarists, such as Jimmy Raney, Jim Hall, Attila Zoller, and Gene Bertoncini, make the pilgrimage to Sea Bright to play duets, talk guitar, and generally socialize with the Farlows.

And Farlow keeps up with the scene, too. just as he did years ago—by listening to records and the radio.”

December 5, 1963”

“Tal Farlow: Turning Away from Fame”

-Burt Korall, Downbeat, February 22, 1979

“Tal Farlow — the name must strike a positive chord if you've been listening to jazz for a while. Before absenting himself from the limelight, this guitarist brought to the music a flock of fascinating ideas, an innovation or two, flashing technique and more than a little of himself.

In all, Tal was on the scene a little over ten years. The 1950s, the Eisenhower decade, was his time. During this period he had a strong effect on fans and his colleagues, making memorable music with the Red Norvo Trio, the Artie Shaw Gramercy Five, and his own trio, featuring explosively talented Eddie Costa on piano and creative Vinnie Burke on bass.

His career prospects were excellent. He was at his peak. Then quite suddenly — or at least it seemed so at the time — Tal picked up his marbles in 1958 and went home. He got away from the big city and its nonsensical hustle, while escaping the "show biz" aspects of jazz so repugnant to him.

‘Perhaps I was meant to be away from New York and places like that,’ Tal says, adding: ‘I got fed up with the backstage parts of the jazz life, the “business” relationships, the pushing and shoving, it seemed that I became increasingly involved with stuff that had nothing to do with music. Though I wanted to continue playing, I couldn't deal with all the other things. So I made a change.

‘I moved to Sea Bright on the JerseyShore with my wife. I like it there. It's quiet and peaceful. It feels right to me. I do things around the house, tinker with tape recorders and boats. I teach a bit and sometimes get out and play, mostly locally. Every once in a while I make a record or appear at a festival.

‘I'm not really a part of the scene,’ he continues. ‘It may sound unusual to you, but I never felt like a professional musician. I never had any desire to be a leader, either. I just wanted to play guitar. I guess I got into the whole thing by accident, anyway.’

Tall, quiet, reserved, basically shy, Tal had a sign painting and display business in Greensboro, North Carolina, when he heard Charlie Christian on network radio with Benny Goodman in 1940. It was an extraordinarily striking experience that changed the course of his life.

‘Christian made music important to me,’ the guitarist says. ‘I rearranged the schedule at my shop so I could work nights and listen to band remotes from places like the Panther Room of Chicago's Sherman House, the Pennsylvania Hotel in New York, Frank Dailey's Meadowbrook in New Jersey and the Hollywood Palladium.

‘I became very familiar with Miller, the Dorsey’s, Basie, Glen Gray and a number of other bands. But Christian was the one who got me moving. I bought all the Goodman-Christian recordings and memorized Charlie's choruses, note-for-note, playing them on a second-hand $14 guitar and $20 amplifier. Though a late starter for music — I was 22 in 1940 — I sure was fascinated."

Tal kept listening to the radio and progressively enlarged his record collection, Lester Young became a favorite to and major influence. After a little while, the budding guitarist noted a link between Christian and the President of the tenor men.

'The conception, feeling and phrasing of their music have a lot in common,’ Tal asserts. ‘I believe Prez was the father of the legato style. Most guys weren't too subtle and didn't play those long lines before his records got around.’

‘With Prez I went through the same process as I had with Christian, I committed his solos to memory — from the blue Decca discs and many of the Basie Okeh and Columbia recordings. I had special favorites — Lady He Good, from Prez’s first recording session in 1936, with the small band: Basie. Jo Jones, Walter Page and trumpeter Carl Smith; that one andTaxi War Dance, Texas Shuffle, Every Tub, Jumpin' At The Woodside, Jive At Five. They all helped me learn what and how to play.

‘Much of what I was listening to wasn't that complicated. Christian's compositions for the Goodman Sextet were mostly blues, with a bit of I Got Rhythm and Honeysuckle Rose thrown in. It was after hearing Coleman Hawkins and An Tatum that new worlds opened up. As I became aware of the chord and interval possibilities, I realized there was much more to music than I ever thought.

‘I couldn't believe it when I first caught Tatum,’ Tal remembers. "I was working late one night. I had my little radio on. I moved the dial and came across this pianist who sounded like three or four guys playing at once. Even as dumb as I was harmonically, never having listened to far-out harmonies and changes, I knew something marvelous was happening.

‘Begin The Beguine, Rosetta— they played about four sides in a row without any commentary in between, I thought to myself, “If they don't say who it is soon, I’m in trouble.” Finally the announcer said, “You've been listening to the piano artistry of Art Tatum.” I took the sign brush and wrote his name on the easel on my work table, it's probably still there. The next day I went to see the music store guy down the street and ordered Tatum's records.’

Living in a small Southern town, Tal had few friends with whom he could share his enthusiasm for jazz. There was a clarinetist named Paul Bell. And when Greensboro became an Air Corps base, he met pianist Jimmy Lyon.

‘Jimmy and I got real friendly. He was very much into Tatum, too. We talked a good deal and made plans to form a group when he got out of the service Eventually we went to New York together, from Philadelphia.

‘How did I get to Philly? Well, during the war, more and more musicians were being drafted. Even territory bands needed players.

‘I was 4-F and got in with this group that was based in Philadelphia. A drummer named Billy Banks led the band He lost his bass player. There were no bassists around Greensboro, so he hired me.

‘I hadn't been playing too long, about two years,’ Fallow recalls, ‘Couldn't read a lick. Still can't. I joined the musicians' union, which was run by the fire department, most of the town's players were in the firemen's band. I left town with Banks but allowed my sign business to continue functioning, in case something went wrong. In fact, I commuted back and forth

‘After a little while, I met people in Philadelphia and got calls for various kinds of work, mostly with trios in cocktail lounges. Guitar was big. Piano, bass, guitar seemed the most popular instrumentation.’

Word began to spread about Tal Farlow even at that early juncture in his career Dardanelle, the pianist and vibraharpist who had a little group in Richmond, heard about the guitarist and contacted him.

‘I was back home in Greensboro, not making any plans to go any place. When Dardanelle sounded me, I went up to Richmond and played for her. I guess she liked what she heard. I joined the trio. Paul Edinfield was the bassist. We made our way north, playing Baltimore, Philadelphia, then New York.

‘It was my first visit to The Apple,’ Tal explains. ‘It was a great time to be in town Charlie Parker was giving oft sparks, influencing every young player in sight. I'll never forget the first lime I heard him at the Three Deuces on 52nd Street. It was fireworks, like hearing Tatum.

‘From that time on, I was at the club as much as possible. On my Monday night off at the Copa, I was at the Deuces before anyone else, waiting for Bird to show. Sometimes he didn't, so the guy who ran the place put up a sign advertising other musicians who weren't there, either. Just to get people to come in.’

Three years later, Tal worked at the Deuces with ex-Woody Herman vibraharpist Margie Hyams, opposite Parker. He listened in awe whenever the great man was on the scene. One evening he recalls most vividly as a bit of a circus.

‘Bird came storming into the club al lengthy absence. The management tried to get him up on the stand immediately He wouldn't be rushed. We were standing in the rear of the place. Margie, Miles Davis, Al Haig. Curly Russell and I watched the comedy unfold. Bird had some sardines and crackers and was eating them with a sense of relish, while the management pleaded with him to come to the stand. They got to the point where they were cajoling and begging him. He kept offering them sardines and crackers. We laughed 'til our sides hurt. Finally he came out and played.

‘When he was doing his thing, there was no comedy,’ Tal avers. ‘He knew his instrument so well, it was so much a part of him. he could play anything he had in mind. The connection between his fingers and thoughts was that direct.’

Like many young musicians of the time, Tal became deeply involved with Bird's tunes, his new changes on standards, his feeling and phrasing, and the lightning tempo that the boppers brought to Jazz . And Farlow played every chance he got.

‘It was pretty hectic. At one point I was performing all night on 52nd St. and working a nine to five job in the display department at Goldsmith Brothers, a store in Manhattan.

‘At the beginning,’ Tal reports, ‘I had some difficulty getting into what Bird and Diz and Miles and those fellows were doing. Because I came from Charlie Christian and played essentially in his style, I found that bop phrases didn’t fall easily on the guitar. But I kept listening and working out my problems until I felt comfortable with the modern idiom.

‘Practicing? I was unorthodox and still am. I practice only what I expect to play on the job. No scales, arpeggios or exercises. I don’t recommend my method. But that’s what I do. Not being able to read, playing entirely by ear, might have something to do with the way I prepare myself to play.’

From whom did he learn the most? Tal mentions that Artie Shaw was an excellent musician and he absorbed a great deal from Shaw and pianist Hank Jones while with the Shaw Gramercy Five in 1953-54. But he insists Red Norvo was the key to his development.

‘Red was a great teacher. I spent about five years with him – on and off – in the 1950s. He kept feeding me knowledge Talk about technique! Red was really fast. He loved to play “up” especially when we got Mingus in the group.

‘I was no faster than the next guy until I went with Red,’ Tal says. ‘Those little arrangements he had played with the Woody Herman band were really tests. I had to work like crazy just to keep up with Red and Mingus – they forced me into the woodshed. I kept practicing until I could play with them without any trouble. By the time we made our first records, I was ready.’

With the Norvo trio, first with Charles Mingus then Red Mitchell on bass, Farlow defined who and what he was it became apparent to the Jazz community that a major player had emerged.

Tal had assimilated Christian and Young, particularly their manner of accentuation and linear propensities. He also understood the implications and techniques involved in the Parker-Gillespie music. Farlow brought too the Norvo trios music a quickness of response lifted by extraordinary technical resources. His ideas and articulation were one. He often resorted to double-timing to get in all he had to say.

His performances on Norvo trio Savoy recordings recently reissued by Arista are harmonically venturesome and sometimes rhythmically complicated, but his playing never sounds unnatural. He often refers to the blues and to the back country areas where he was reared. Like Red, he has a love for melody and it flows through his commentary. Even as he moves afield and abstracts an improvised sequence, the melody somehow lingers, simmering just below the surface.

'I guess I’m always looking for good melodies, the good tunes with unusual harmonies.’ Tal says. "When I played club dates with society bands. I got into this thing where I would seek out particularly interesting obscure tunes to play It kept me from being bored.’

When Tal cut loose from Red, he played periodically with his own trio in New York. The unit's home was The Composer, a now-defunct Jazz room on Manhattan's East 58th Street. Eddie Costa and Vinnie Burke worked hand in glove with their guitarist/leader.

Tal was then in excellent form. Penetrating on ballads, he was awesome on the taster tunes. Costa's ability to improvise with enormous energy and imagination often made the evenings unforgettable. Vinnie held everything together in an unobtrusive manner, making pertinent comments when his turn came.

Like many good things in music, the trio didn’t lust long enough to truly take hold. It was here and gone, and those of us who heard it didn't realize how good it was until it no longer existed. Vinnie went his own way. Eddie died a few years later in an auto accident and Tal moved to Sea Bright. His residence in the Center of things was over.

For several years, there was silence. Tal's contract with Norman Granz's Verve label ran out in I960. No one knew for sure what he was doing. It was almost as it he had never been.

‘During that period, I worked in New Jersey.’ Tal explains, ‘I played all kinds of jobs. Many of them had nothing to do with Jazz. Most of the time the players didn't know me. I felt there was no necessity to concentrate entirely on Jazz. I found I could have fun playing a variety of jobs, as long as I didn't have to read.’

Finally in 1967 Tal came out for a while. Jazz disc jockey Mori Fega brought the guitarist back into the foreground, if only temporarily.

‘It was difficult to persuade him, but finally he decided to make the move,’ Mort says. ‘The man is truly modest, self-effacing and reticent. He has no idea of the extent of his talent.’

Tal picks up the story.

‘Mort got me together with pianist Johnny Knapp. Johnny, who has the same kind of rolling power and sensitivity that Costa had, was working at the Little Club in Roslyn, Long Island, Mort drove me out and I sat in with John, Ray Alexander — the vibes man - and drummer Mousey Alexander. It felt pretty good. Then John came out to my house at the shore and we got into some things. He suggested “a doctor who plays real good bass.” That turned out to be Lyn Christie. We played together, got to know one another, then began work at the Frammis on new York’s East Side – a gig that Mort had set up for us.’

The Jazz audience found the trio exhilarating Tal's playing hadn't essentially changed. Sharp, together, and more mature, many evenings he was fantastic, tapping a variety of feelings. Because of his reticent personality he seldom drew attention to himself allowing his colleagues to open up, encouraging an exchange of ideas,

As New York Times critic John S. Wilson pointed out, ‘He is heard less as a soloist with accompaniment than as part of an ensemble. His electric guitar and Mr. Knapp's piano are constantly dancing around each other in musical conversations full of delightfully responsive passages.’

‘Some great music was made during the Frammis engagement,’ Mort Fega notes. ‘It would have been great to record Tal live. But I wasn't able to prevail upon him to allow it.’

A flash and Tal was gone again.

He emerged briefly in 1969 to make an excellent record which Don Schlitten produced for Prestige. Then titled The Return Of Tal Farlow, now included in the Prestige two-fer Tal Farlow—Guitar Player, it features a small group of players with close rapport: Alan Dawson (drums), John Scully (piano) and Jack Six (bass). Dawson and Scully are frequently quite surprising and Six does his job particularly well.

As for Tal, it is as if he had never been away from the scene. Impressive ideas, generally expressed with great clarity, identify his performances. The up-tempo items are bursting with juice, while his ballad work further reveals his ability with harmonies. Farlow in '69 was still a musician of consequence.

During the past decade, Tal has been in and out of things. He participated in several albums produced by Schlitten, including the late Sonny Criss'Up, Up And Away for Prestige and Sam Most's Mostly Flute tor Xanadu. Recently there have been two Farlow albums on Concord, and Tal has played the Newport and Concord festivals, touring a bit with a Newport group.

But for all intents and purposes, he is a part-time player. A homebody, Tal stays close to his Sea Bright base, doing most of his musical work locally. For a while he was at the Blue Water Inn. More recently, he was the attraction at The Quay in the seaport town.

Has he been listening to much music? Some. Enough to tell you that JoePass and George Benson are playing great, and that there are some young guitarists who are frightening. As for pop players, ‘I really don't know what most of them are doing. The volume puts me off. I just haven't heard anybody working in the rock or pop style that makes me ask 'Who's that?’’’

‘My own playing? Sometimes I think it's changed with the times until I listen to the old records. I guess I'm pretty much the same, except I don't perform as much as I once did. Sometimes the lay-offs affect my work, other times they don't.’

The future for Tal Farlow, according to the man himself, probably will be much like his recent past. ‘Looks like I'll stay around home. I have no idea when I'll play in the big city again. I his past year was a difficult one for me. I had a lot of illness in my family and spent a great deal of time down south in North Carolina.’

‘I still tinker,’ he adds. ‘I guess I forgot to tell you about this electronic frequency

divider I've put together. It's built into the stool I use. Tell you what happens when I perform: I play a note, the divider lowers it one octave, and the new note mixes in the amplifier with the original note, giving the effect of another instrument playing along with the guitar one octave down.’

'The wiring of my Gibson guitar is a little different to make it possible to get this effect. But the instrument can still be played in a conventional manner. Generally I take the divider on the job with me. It can make the evening quite enjoyable.’

‘I like trying for new sounds, experimenting with the instrument,’ Tal says. ‘You know about my interest in electronics. It's one of the things that keeps me stimulated and busy. I'm into a bunch of things.’

‘High on my list is playing. But fortunately, I don't have to be out there, dealing with situations I find difficult to handle. I don't need expensive things or a hectic life. So I stay in Sea Bright.’

‘Only one thing is certain,’ he concludes. ‘Before I play for large audiences or record again, I'll have worked harder than ever to get into shape. I always try to stay on a certain level. I owe that much to myself.’

“Tal Farlow: Have Guitar, Won’t Travel”

-Les Jeske, Downbeat, January, 1982

“Following Tal Farlow's career has been a ‘now you see him/now you don't’ prospect for the reticent guitarist's fans, but with a new film documentary, a new record company, and a new (old) group, he's back in the limelight—for now.”

“He is like Haley's Comet. Every few years Tal Farlow pops up again, electric guitar ablaze. And then, after a taste of press and fan adulation of which few in jazz can boast, Tal Farlow seemingly disappears. Nobody in the history of jazz has been the subject of more ‘Whatever Happened To...’ or ‘The Return Of...’ articles. One of the most influential electric guitarists since Charlie Christian, Farlow has a technical facility on the instrument few can match.

His sense of swing and his excellent taste add to the high regard in which he has been held for some 30 years now. Yet, just when it appears that Tal Farlow is back on the scene for good, he seems to pull one of his disappearing tricks. And when he "returns" a few years later, the same thing starts all over again. People turn out to hear him in droves, and everybody asks him where he's been and why he's shunned the jazz public.

I sense Tal Farlow's overwhelming shyness as soon as I sit down with him, backstage at a New York club where he is performing with his longtime band mate and friend, Red Norvo. Born 60 years ago in Greensboro, North Carolina, Farlow retains the air of a farm boy — gentle and unassuming. He answers questions painfully and appears to be honestly surprised at all the fuss people make about his guitar playing and about his so-called reclusiveness. He skirts the question of why — when he could have carved out a continuous career as one of the premier jazz guitarists — he preferred to work mainly around his home in a small southern New Jersey town as an occasional guitarist in local bars and as a painter of signs.

Is it because of his distaste for the fast-paced New York City"jazz life?"‘Uhh . . . well, I'm honestly not that crazy about New York City,’ he answers.

So he turned down offers that continued to come in from club owners and concert promoters, to avoid the city? ‘I wasn't pursued that much,’ he replies somewhat unconvincingly. ‘I wasn't consciously avoiding anybody. I got some offers I didn't think were exciting, and I just didn't take them. I don't remember getting that many calls. Maybe, if you added them up through all those years, you might call them a lot. It's just that what I was doing wasn't in a place where it got any attention. I chose to stay near my home in Jersey— it's a resort area and, in the summertime, it hops. There's quite a lot going on down there.’

But, certainly, there had been offers from Europeand Japan, where the jazz appetite can be particularly voracious? ‘Well, the tours that were offered to me, I didn't think would be possible. Either that or ... I've heard stories about the guys who came back, where they pay you so much a day and book you in two places the same day and things like that.’

I sense that there is something missing as Tal and I talk about his life in New Jersey as the local musician, sign painter, and sometime guitar teacher; about his current spurt of activity - working with Red Norvo, recording for Concord Records, touring with Herb Ellis and Barney Kessel; and about his early days as a self-taught guitarist weaned on Charlie Christian solos. I feel a patina of wistfulness about the man. I ask if, looking back, he has any regrets. He thinks deeply about the question, as he does about all the questions, and quietly responds.

‘Well, there are things that happened, you know. I guess any business you can be in you'll feel, “Well, there's got to be something better than this.” Perhaps I should have gotten into the pace I'm into now, earlier. But I enjoyed the other time, too.

"You see, not ever having had any training as a musician, it's always been sort of hard for me to feel really comfortable. Like on a record date — these guys are reading stuff which they've never seen before. I can't do that and, you know, I've got to feel a little different. I feel a little inadequate. And so I really haven't called up people and said, “Do you want to use me on a record date?” I don't do that because I got myself embarrassed a few times. Because when you tell somebody you can't read, especially if I'm working with Red Norvo or somebody, they figure, “Well, he's got to be pretty good to have worked with Artie Shaw or Buddy De Franco.” It doesn't look too good. When you say you can't read, it doesn't mean to them that you can't read, it means like, “Well, maybe I don't read too good” or “I could read better,” or something like that.

‘But when you have to say, “Well, what is that note?” or “Well, let's see, it's on the third string and I think it's somewhere around here....” If I say, “Oh, just play the phrase for me on the piano’ and he plays it, then I can play it. But record dates don't work that way.

‘I know one time when I was working with Red, there was a tenor man who was working with Tommy Tucker's band. Now that music wasn't really involved, as well as I remember it. But there was a part in there, and he asked me to do it. I said, “Louis, you know I can't read.” He didn't know me well enough to know that I couldn't read at all, and he said, 'Well, there's no problem, there's nothing to read anyway.” Well, it turned out that they had me read a flute part. Here I was, and all these guys were thinking, “Gee, Tal Farlow, he's with Red Norvo” — young guys — and I couldn't read the damn thing. Finally, they had to give it to somebody else. It's embarrassing. How many times do I have to go through with that? That's when I got back to sign painting.’

It all falls into place. Tal Farlow, one of the most technically facile of all jazz guitarists, feels "inadequate" over his inability to read music. Basically, he admits later, he is uncomfortable going into a situation with a rhythm section he doesn't know. All those club owners and concert promoters and record producers had to do to lure Tal Farlow the 55 miles from his New Jersey nest to New York City was to offer him a musical situation in which he would feel comfortable: namely, to get him musicians he had worked with in the past and with whom he knew he was compatible—like Red Norvo, in whose influential trio (along with Charles Mingus) Tal first gained wide recognition.

On the day we speak, Tal is in the middle of a tour with Norvo and bassist Steve Novosel. Tal and Red have worked together periodically since the dissolution of the trio (most notably in 1969 on a Newport All-Stars tour), but this is the first time they are purposefully recreating the sound and feeling of the classic unit. Novosel is a fine, rich-toned bassist and, with characteristically low amplification, the three men easily recapture the Tinkers-to-Evers-to-Chance interplay of the trio with Mingus (and, later, Red Mitchell). A typical set starts of! with a playful, easy-tempoed All Of Me, moves through a gently swinging Here's That Rainy Day, into a reflective Baubles, Bangles, And Beads, and on through Cheek To Cheek and Sunday— the three players keeping their eyes fixed on one another. Red's "poop-poop" sound on the vibes meshes brilliantly with Tal's crablike dash over the fretboard, and they occasionally include a two-chorus dual improvisation that is hypnotic. Before the set finishes, Tal will be featured on a drifting, exploratory My Romance played entirely in chime-like harmonics. The set will conclude with a blues romp on St. Thomas, an elegant reading of Sophisticated Lady, and an all-out, finger-cracking Fascinating Rhythm. It is clear from the pixieish grins that the three men center-stage have had as much fun as the audience in the packed club.

![]()

Before signing on with Red Norvo in 1950, Tal Farlow had cut his teeth with Dardanelle (who brought him north from North Carolina), Margie Hyams, and Buddy De Franco. Like so many others of his generation, Tal first began to pursue the jazz guitar after hearing Charlie Christian on remote broadcasts. ‘At that time I was working as a poster artist,’ Tal recalls. ‘I made posters for stores and things. I rearranged my hours so I could work at night. The people who owned the sign shop would take the orders in the daytime, and I would do them at night because at that time they were doing these band remotes, like Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw. All the good music was on the radio, and they would just do one band after another.

‘I could already play the guitar a little bit, but the guitar was, in most cases, a part of a hillbilly band—you know, with three chords. Then Charlie Christian would come on like a sax, and it sort of made me think, “Now, I've got an instrument here that can conceivably move out-front.” I hadn't tried to play any single-string till then. I got those records and I learned to play those solos note for note.’

Before the '40s were out, Tal would fall under the spell of two other jazz masters, Art Tatum and Charlie Parker. His ability to synthesize these various elements helped bring him to the attention of Norvo, who asked him to join the vibes/ guitar/bass trio he was about to form in California. ‘I went out with Red,’ Tal says, ‘because I did not have any reason not to. The prospect of working with Red Norvo was attractive, and I had never been to California. Red Kelly was the first bassist, but he left to rejoin Charlie Barnet. Red said he knew Mingus and we located him delivering mail, I think, in San Francisco. We called him up and he came down. We spent two or three afternoons a week at Red's apartment rehearsing. We just rehearsed a lot and worked a little place called the Haig, and it just took off. It might have taken longer than it seems like it did now, looking back over 30 years or so.’

It was here that Tal Farlow began to earn his reputation for speed and technical proficiency. ‘I didn't have any choice,’ he says, with typical understatement. ‘I mean, if Red was going to play it this fast, that's how fast it's going to be. It was rough at first. The trio was a product of each of us having little tricks that would fill in for the fact that it was only three guys. In my case, it was playing harmonics and doing a bongo-type effect on the guitar.’ The trio was a sensation with fans and critics alike and began recording a series of highly successful albums for Savoy.

In Charles Mingus' book, Beneath The Underdog, he describes in rather bitter tones the incident that led to his leaving the trio: "So now you've got a job again, boy, in a trio, boy, with a famous name. The leader has red hair, boy, and the guitar player is a white man too, from North Carolina. You're playing in San Francisco and making records and the critics are writing good things. Boy! Boy! Boy! ... How does it feel when the Redhead's trio is asked to do an important, special television show in color? It feels great. At night you're playing in this first-class club, and daytimes you're rehearsing in the studio. One day during a break you're tuning the bass and you see this producer or somebody talking to the Redhead across the room and they're both looking at you. You feel something is wrong but you don't know what... While you're packing up, the Redhead comes over and says something like this: 'Charlie, I'm sorry to tell you but I have to get another bassist for this show. We'll continue at the club but I can't use you here.' What do you say? You ask the name of the new bassist, of course. He tells you. The bassist is white... So you quit the trio... You wonder and wonder why he didn't tell you face to face or why he didn't walk off the TV job—some leaders would have. He wanted the money too bad...."

‘That's inaccurate,’ says Tal, firmly. ‘Red tried to get him on it, but what happened was that Red and I had 802 cards and Mingus didn't have one. And, you know, the union was a little bit heftier in those days than it is now. Now I don't think I would have gone for it. I would've said, “We came as a group, we should stay as a group.” But, whatever the reasons, it had nothing to do with black and white.’

Mingus was replaced by Red Mitchell and the trio stayed together until 1953, when Tal left to join Artie Shaw's Gramercy Five. After a year with Shaw, he returned to Norvo and remained until October, 1955. It was then that Tal Farlow would start the shell game that would mark his career for the next 25 years — turning up at a club or on a record, grabbing the limelight for a minute, then retreating back to his nest on the Jerseyshore.

Farlow insists he wasn't hiding from anybody during his long absences from the jazz mainstream, nor was he inactive. I'm sure that more than a couple of keen-eyed jazz aficionados did a double take after stopping into some local hole-in-the-wall bar on the Jersey shore and finding Tal Farlow as part of the trio in the corner. During the afternoons Tal wasn't hiding either, he could be found on his back porch, quietly lettering signs, or inside his home, giving lessons to some lucky guitar student — one who learned how to read before he sought out Mr. Farlow.

![]()

‘I tell them right away that we're not going to get into reading,’ says Tal. ‘The guys that I've been trying to teach are already into that. You can play jazz without being able to read at all. I mean, you can play tunes and things like that. Jazz now is in so many different boxes that I guess you have to read to be able to bring some of it off. I certainly don't advise anybody to neglect that. That should be number one. But what happens when you're playing guitar — it's easy to learn to play enough so if you don't get into reading right away, it would become too dull because you can play a lot more interesting stuff than what's written down there for you to learn to read.

And, in my case, it was just so discouraging. I was playing stuff that probably wasn't even easy for a fairly good reader to read. That's my cop-out. If somebody was to hand me a transcription of one of my own solos it would take me a little while to

figure out which solo it was.’

So Tal Farlow takes students who are already well-versed in the basics. He tries to take them down the road he learned on — listening to solos and trying to develop a feeling for jazz. ‘What I'm trying to do, in the teaching business, is have them utilize what they've learned in the way of scales and modes and arpeggios and things like that. Sometimes they play these things that come out and, to my ear, they don't belong. There are all these things that have an ambiguity to them, that can almost fit anything. But that also makes them sort of not have much meaning. Sometimes guys come and show up and don't have the ability, say, to just stay in meter, who just keep getting lost. That's something that I don't think you can ever learn. If you don't have the ability to just stay with the time, well, you can't play with anybody but yourself.’

Those are the students Tal, reluctantly, doesn't accept. He is also quite generous to those guitarists over the years who have absorbed some of his own methods. ‘I can hear the things they're playing that are from me, but I remember that I also copped things from other guys, so I think it's possible that they got it from the same guy I got it from. In other words, if I heard something that maybe might have been inspired by a Charlie Christian phrase, I couldn't say that he copied it from me when I got it from Charlie Christian."

Farlow credits two things with his current motivation to become more visibly active. In Concord Records he has found a company that, he feels, will help him take care of such things as arranging tours and making sure that he has the musical situations that he likes, both for records and personal appearances. It is they who thought to reunite Tal with Red Norvo. Concord's guitar roster is quite dazzling — Jim Hall, Barney Kessel, Herb Ellis, Cal Collins, Laurindo Almeida, and Charlie Byrd all record for the label — and Tal feels that they will help him sort out the ends of the business he finds less than tasteful.

The other factor that has led to his current activity is the completion of Talmage Farlow, a 60-minute documentary on the guitarist's career and unorthodox life by young filmmaker Lorenzo De Stefano. ‘The fact that he can go out and raise $100,000, or however much it took to do that, that's inconceivable to me. I haven't had that kind of a colorful life, you know, at least the way it appears to me.’

The film shows Tal in his various guises — lettering a boat called Fat Chance, jamming in a local club with drop-in guitarist Lenny Breau, giving a guitar lesson, and appearing with Tommy Flanagan and Red Mitchell in a New York concert. The interest in the film, which quite succinctly wraps up the various sides of Farlow, has opened Tal's eyes a little to the high esteem in which he is held. On the day we speak, Tal has still avoided seeing the film. He is quite sure that he would wince at his guitar playing (of which he is highly critical) and would be deeply embarrassed by the entire experience. (One particularly moving passage has Tal's wife, Tina, recalling one instance when, "He was so despondent he cried, ‘What have I done with my life? What have I accomplished?’")

Nineteen eighty-one was a hallmark year for Tal Farlow: he reached his 60th birthday; had successful engagements with his own trio, with Red Norvo, and as part of a three-guitar unit, along with Herb Ellis and Barney Kessel; toured outside of America for the first time (a month in the United Kingdom); and recorded several times for Concord Jazz. He claims that he has ‘a little brighter spark of enthusiasm’ and is even contemplating leaving southern New Jersey for a home in New York City or southern California. There are still legions of guitar fans who refuse to believe that Tal Farlow is back amongst them for good.

One of the things that will keep Tal Farlow on the scene is his ability to continue to play in musical situations with which he is comfortable, ideally having his own working group. ‘The difference in the business between the time Red, Mingus, and I worked together and now,’ he says, ‘is that then it was possible to make a living and travel around as a group. Now, to put three guys up in a hotel, or to pay them enough money to cover it, you've got a big nut before you even pay them any salary. So now it's gotten to where the artist goes and plays with two guys who already live there. That takes away what little bit you gain by being organized, and the way I like to be is to have a great deal of organization. I always admired that about Oscar Peterson's groups. The product showed that they had worked on it, and it was very interesting. It wasn't a jam session.’

‘I would like to have, say, a Red Norvo Trio when Red doesn't feel like working, if I could get a vibes player and a bassist, even with the handicap of having to take a lot less money, just to have an organized group, because, to me, that's important enough. Herb Ellis and Barney Kessel, for example, have a book for the bass and, I guess, the drums, and they tour and they say, 'Well, we're going to play this. Their way of having the thing organized is to write everything down for the bass player. But that'll never come off as good as four guys who work together all the time, like the Modern Jazz Quartet did. I've got enough built-in insecurity that it is a big help to me to be on the bandstand with something where I have some idea of what's going to happen. I'm not going to be surprised by some guy going off on a tangent.’

Is Tal Farlow here to stay? It seems a reasonable possibility, but don't put any money on it. Suffice it to say that, at the moment, Farlow is exceptionally content. But at least you know that if he does follow his usual will-o'-the-wisp pattern, sometime when you walk into some local Dew Drop Inn or go to have a "For Sale" sign painted somewhere, there is the possibility that Talmage Holt Farlow will be at your service, in his own inimitable way.”

Tal Farlow’s records, many of which were made by Norman Granz for his various labels, were unavailable for many years. The advent of the CD found many of these rs-issued in limited form on Verve Records which also leased them to Mosaic Records.

Thanks to Michael Cuscuna and his fine team at Mosaic, a collected version of Tal’s music was licensed from Verve and issued in April 2004 as The Complete Verve Tal Farlow Sessions boxed-set [#224].

Michael asked guitarist Howard Alden to write the insert notes booklet for the set.

These include a track-by-track analysis as well as an overview of the highlights of Tal’s career.

Here are Howard’s opening and closing paragraphs: