© - Steven A. Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

Richard Terrill is the author of the memoir Fakebook: Improvisations on a Journey Back to Jazz, and two collections of poetry, including Coming Late to Rachmaninoff.

He graciously consented to allow his essay to be posted to JazzProfiles.

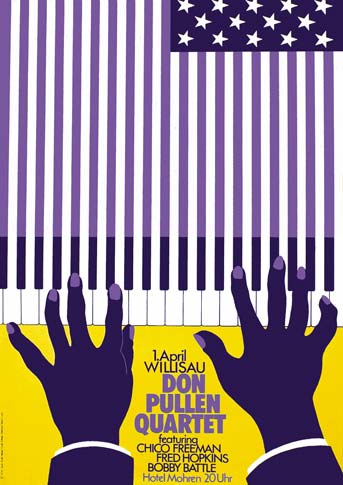

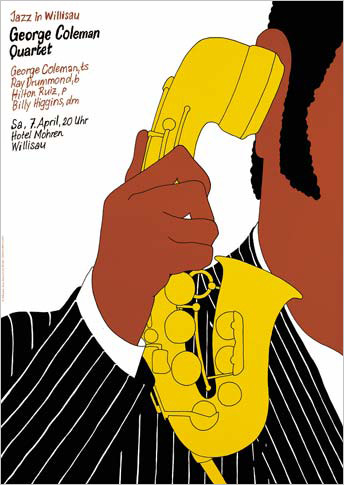

Since Mr. Terrill’s article in its original form did not include any images, with the exception of the lead-in photograph of Bill Evans, I decided not to populate it with additional photographs or graphics in order to present his writing without interruptions or distractions.

© - Richard Terrill, copyright protected; all rights reserved. Used with the author’s permission.

START here

1. his music, like his personality, had a questioning quality

2. he wasn't a narcissist, apparently

3. he sought the essence of the material in its harmonic implications

4. Miles Davis said, "It's a drag he's dead. Now I'll never get to hear him play Alfie' again"

5. he started as a flute player

6. he didn't live as long as he might have otherwise; he didn't live to be old

7. whereas many people don't eat properly when they're kids, he didn't eat properly at the end of his life. Malnutrition was listed as a contributing cause of death. Coffee. Also cocaine

8. he loved to golf, bowl

9. his long-time girlfriend and first wife Eliaine threw herself in front of a subway train in 1973

10. he had lifelong feelings of inadequacy

11. he played early on with saxist Herbie Fields, whose career ended tragically in suicide

12. he was left handed, which may account in part for his chordal proficiency

13. he wasn't African American, and he never resided permanently in a foreign country to escape racial prejudice at home

14. at his death, Oscar Peterson said, "Maybe he found what he was looking for"

15. he knew a great deal about the novels of Hardy and the poetry of Blake

16. loan sharks threatened to break his hands

17. "I had to work harder at music than most cats because, you see, man, I don't have very much talent."

Thesis

Why would one of the great artists of his day be so self-destructive as to kick a heroin habit only to start a cocaine habit? "When I get into something, I really get into it," he is known to have said. Does that explain?

Shortly before his death he told his young bass player how amazed he was at the insidiousness of his new drug.

We can read that his life was a fifty-year-long suicide. We can read that he was a nice man, had a sense of humor better than your grandfather's, wanted a child and when he had one thought his life was complete, then got a divorce. Dying of cocaine, he thought he was happy.

Some jazz musician junkies played the music only to get money to score. Chet Baker would forget his trumpet on a bandstand in his haste to shoot up. Charlie Parker had to borrow money for cab fare. But Bill Evans practiced constantly. "I heard him practice Ravel, Debussy," his wife said after his death, "but I never heard him practice jazz."

"You don't understand. It's like death and transfiguration. Every day you wake in pain like death and then you go out and score* and that is transfiguration. Each day becomes all of life in microcosm"

Leaving my footprints

nowhere

south or north

I go into hiding

here by the bay full of moonlight...

Muso Seki (W.S. Merwin, tr.)

Bill Evans is given credit for inventing the jazz piano trio. Think about it: no blaring horns, no chick singer, nothing to dance to. A piano is an instrument that can't color or bend tones. What it is, it is. It's so common as to be in every parlor or basement, so playing it is like making poetry from the words printed on a menu or a cereal box.

In the years between Sinatra and the Beatles, Bill Evans formulated a new jazz instrument consisting of three people joined at the beat— piano, bass, and drums. This rough beast was amorphous, something to be agreed on, not timed.

And of the three players, it was the bassist and the pianist who most played as if from the same body. It's not you play what I play, which would be an untrained listener's first assumption. It's you anticipate what I’m about to play based on what I'm playing right this second, what I've played since the tune has begun, what we've played in all the nights/years we've worked together, and on the basis of everyone who's ever played or recorded this tune.

And of the trios Bill Evans led, it was his first, with bassist Scott LaFaro, that was the most prescient, where the piano and bass first melded into this new animal. No one accompanied anyone else. Rather, partners.

Play something that you think will fit perfectly— not too obviously, not unsubtly—with what you think I'll play. Surprise me. But don t get in the way, don t piss me off.

The audience? Are there people sitting out there? Ok, they're allowed to listen over our shoulders.

They don't understand.

Then LaFaro was killed in a car wreck, aged 25. Bill Evans was 31.

His Reluctance

—"The trouble with Bill—and, as much as anything, that was the cause for our deciding to record him live—was always persuading Bill to play at all." -Orin Keepnews

—"Of course, Bill would never have let any work out at all if he wasn't compelled to support a career."—Nenette Evans

"It is a peculiarity of mine that despite the fact that I am a professional performer . . . I have always preferred playing without an audience."

You Don't Understand

Bopsters of the fifties often took up heroin because Charlie Parker used it (even though Bird said dope never made anyone play better). We listeners like to plug in the sociological explanation that the racism of the day drove these great but disrespected artists to despair.

Bill Evans was white. ("He was a punk," said Stanley Crouch, an African American critic, years after this death.) While he was often broke, he never lacked for work except when his habit got out of hand.

The pain is in the music. That much we can hear, especially in the ballads he was famous for. Why do we assume that the life of someone who was a great artist should be more easily explained than the mystery of our own experience? A fact is not sound. A collection of facts does not necessarily carry the logic of music, or even the music of logic.

Biography is tyranny.

The White Tuxedo

One story has it that near the end of his life, performing at the Village Vanguard, he showed up late for the gig, dressed in a white tuxedo and eating a chocolate popsicle. He was in a bad state, but played beautifully, all but unaware as the chocolate melted over the keyboard.

"The Perplexity of Never Knowing Things for Certain"

A typical audition with Bill Evans' trio would have the candidate come down to some place like the Village Vanguard and sit in for the entire night. At the end of the evening, the pianist would say nothing. Maybe a pleasantry, a nod of the head.

He rehearsed his trios only a handful of times in his twenty-one years leading them. It wasn't necessary for him to tell his bassist and drummer what tune they were about to play and in what key. He just started playing.

He also apparently never wrote a set list in advance of a performance. He did, however, once copy down on a bar napkin for a young pianist in the audience the chord changes for a new composition he had just performed in the previous set.

That's it. He’ll call you.

I'm a jazz saxophonist. My drummer and I have a running joke. In days past, when either of us would sub on a gig with some bandleader we didn't know, especially older guys, "ear guys," who play everything without a page of music in front of them, the bandleader would call a tune by name, but not tell you anything about it. He never said, "When you get to the B section, the changes go up in fourths, and then there's a Latin thing happening." Nothing like that. Instead the leader would simply say, "Don't worry, you'll hear it."

And sometimes you would hear it. But there would be that moment of uncertainty when you didn't know if you would hear it, and what would you play then? That was the worry.

Perhaps that's where art resides, or maybe this moment merely marks the difference between professional and amateur.

But that's the punch line of our joke: you’ll hear it. Someone in our band brings in a chart to rehearsal: "It's in nine four time, kind of a tango, I wrote if for the funeral of my aunt."

And the drummer and I say together, "Don't worry, you'll hear it."

Who Owns the Silence?

The central problem is that there's so little work for jazz musicians right now. It's the weak economy, everyone says, though they offer that as the rationale for anything: bad weather, impotence, a taste for chocolates.

That and the fact that jazz popularity (to the degree that jazz is ever popular) goes in cycles. Right now, we're at a low point in the cycle, when people who wouldn't be listening anyway don't particularly think it's cool to go to a club or bar where local jazz musicians play.

Or club owners think that their customers think this way. And so if you look at the calendar for one of the few jazz clubs in my city, you see R&B on a Tuesday, a Klezmer/rock fusion on Thursday, a few national acts blowing through town ("song writer Jimmy Webb,""The New Soul Review," Lucinda Williams), and the rest of the week chick singers singing what Sinatra stopped singing years before he died, in the last century. But at the best jazz club in my city, instrumental jazz is seldom on the schedule, and that performed by local players like me and my band mates, almost never.

I drive friends through town and point out the places I used to play (seventy five, maybe a hundred bucks a guy, one free drink) which are now closed or have cut out music: 1. Rossi's— belly up. 2. The joint on Washington—It's now a tiki bar. 3. Café Luxx—There's still a graphic of two saxophones among the letters painted on the window outside the bar. Cafe L-U- sax-sax. But no live music inside. 4. 5. 6. And so on.

Jazz? "Don't' worry, you'll hear it." Or you used to.

Telling the Difference

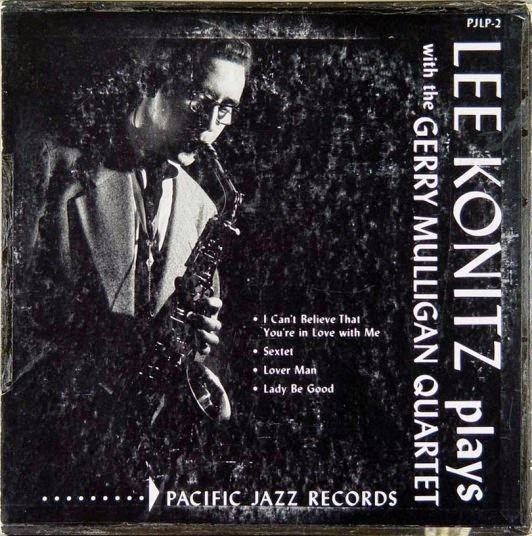

Of the four black men in the Miles Davis Quintet of 1959, John Coltrane is the one who most objected to having a white man at the piano. Bill Evans eventually left Miles partly because of the racial tensions among the band members, but went back for a studio session once when Miles asked him to. That session became Kind of Blue, generally held to be the greatest jazz album ever.

"We just really went in that day and did our thing."

If you're white and leading a regular life in this century, it's hard to imagine what it must have been like to be a genius and black in 1959. Bill Evans had to imagine it then. Hair slicked back, dark-framed glasses, cardigan sweater buttoned up, puffy young face, quiet. He looked more like an accountant than a jazz musician. Everyone said that.

Upon joining the group, Evans was told by Miles that there was one small matter of initiation: "You have to fuck everybody in the band." Bill walked away and thought about it for fifteen minutes and returned. 'Tm sorry, I don't think I could do that."

(He had a sense of humor better than your grandfather's.)

"My man," Miles laughed.

In 1992, before a rerelease of Kind of Blue, an astute engineer discovered that on the first three cuts of one day of recording, the tape had been running slow so that on every pressing of the album to that point, some of the music was about a quarter step sharp.

For over thirty years, no critic or player or listener had noticed the difference.

On the Need for a Sound Business Plan

Larry, the piano player I work with, says that people opening a bar or restaurant should ask the musicians whether or not the business will fail. We can tell right off. One place, a wine bar and adjacent deli, offered to pay the musicians only in coupons for their own establishment: $75 in credit, plus a free (nice) dinner and all you cared to drink. Fine, we did the gig.

But then the next time we played the place it was fifty bucks in coupons, and you could have a pizza or salad but not the main entree, one glass of wine. Well, ok ....

The last time we played there it was fifty bucks in coupons, and go hungry and bring a flask. I used some of my credit from previous gigs at the deli and got home to find I'd bought moldy cheese and stale crackers. Some overpriced canned soup.

I was about to go to the place with my wife to use more of my stash of coupons. I checked the bar's web site only to read that the place was closing in a week. No surprise to the musicians. So I called Larry, who'd played there more than me. Larry ate dinner there every night for the following week, just to use up his credit with the joint before it folded. It was the principle of the thing. He brought his friends, maybe an ex-girlfriend. Bought drinks for strangers.

Scott LaFaro

-"While we were listening to the tape, Bill was a wreck, and he kept saying something like 'Listen to Scott's bass, it's like an organ! It sounds so big, it's not real, it's like an organ, I'll never hear that again.'

"Bill continued to play 'I Loves You, Porgy' over and over again, almost obsessively—but almost always as a solo number.

"After LaFaro's death, Bill was like a man with a lost love, always looking to find its replacement."

-Gene Lees

A Controversy

Ken Burns made a 19-hour series for public TV on the history of jazz. In the series, Burns spent two entire two-hour episodes on two-year periods in the 1930s, a decade in which jazz was at the height of its popularity, but perhaps a low point in innovation and complexity. To the last forty years of jazz in the twentieth century Burns devoted one two-hour episode.

In the entire series, Bill Evans' music is discussed for ninety seconds. None of his music, other than from Miles'Kind of Blue, is played.

A True Story

The speaker, an African-American poet, asks for a show of hands. How many of the fifty-odd college students attending this lecture on the interstices of music and writing know who Bill Evans was? No one raises a hand.

The poet reads a reminiscence about his father hearing Bill Evans play at a Black club on the South side of Chicago in the 1950s ("That white muthafucka can flat-out play"). Behind his words a pianist plays a skillful imitation of Bill Evans.

In her playing, I can hear the close, impressionistic voicings, as if Debussy had done drugs and lived, as if Satie had set the copy of newspaper ads to music just yesterday, and not a hundred years ago. I'm probably the only one in the audience who can hear this in her playing. The college students in the audience can't hear it.

I hear the woman's variations of touch on the keys, the implied rubato that nonetheless offers a pulse and a pace. Listening to her is like walking through a gallery at the Met and seeing a student with an easel set up before a Vermeer. The yellows and blues against a dark background. The poetry of composition—light rhyming with light. That not caring too much, done so carefully. We watch the student before the master and smile quietly, since this brings us a warm feeling about the continuities in art, and by extension in life, that what is great is rare and will always be. That great art, copied by one, is better than bad art embraced by all.

How to describe music, anyway?

As if Ravel had given in to his late desire to play jazz, which he loved ....

Jazz bandleader Stan Kenton told a story about himself as a kid, trying to sneak into a Paris club to hear jazz. He was too young to drink, even in France. The concierge finally said, ok, just go sit in the corner with that old man. His name is Maury.

And it went like this for several evenings. Go sit in the corner with Maury, kid.

Years later, Kenton learned that the old man had been Maurice Ravel.

"The questions I might have asked….”

After the poetry reading with the piano accompaniment, the director of the college jazz program in my town is talking to my drummer and bass player. He sometimes wonders why he's spending his life training students in the jazz idiom. What future can there be in this music that no one cares about? It takes a lifetime to learn to play, and what of it then?

Who was Bill Evans?

-"He seemed to absorb from William James the perplexity of never knowing things for certain. Even though there are no absolute answers and never will be, one has to act anyway." -Sister-in-law

-"He sat sort of erect at the piano, and he'd start to play. And pretty soon his eyes would close, and his upper body would gradually start to lower itself, until finally his nose would be about an inch away from the keyboard. It was as if he were abandoning his body to his muse—as if the body evaporated, and there was some direct connection between his mind and the piano itself."—Larry Bunker, drummer

"Bill Evans. He was a punk."

Scott LaFaro: A Fiction

The bass and piano were like two empty sleeves of a fall coat, filled by ghost arms.

The bass player and piano player were like two poles of a planet that through some magnetic accident met on the same ice floe, which got smaller and brought them closer and closer together until some new electric thing happened.

The implication of one is stronger than the taste of coffee, the smell of dead leaves in a rainy fall. Not one the number, not a person alone— that's a given in our lonely lives. Not one as in the first point in a list—top dog, lead dog, numbah one. But one as in the downbeat. That point in time that two or more jazz musicians (or classical players, blue grass pickers, rock stars, lounge lizards, studio cats)—must agree the start of the measure is. One is like the place the carpenter thumbs down the end of the tape measure. Measure twice and cut once, remember? Well, not in improvised music. In jazz you just eye it up and then slice that uncut diamond into the purest component of light.

How did Scott La Faro know what not to play? They come to the bandstand in the dark basement club. Eisenhower is just off the scene, Ornette Coleman just on. LaFaro played around one. He played around the root—like loose soil, like the earthworm or the microbes taking waste to nutrient. The root is the foundation, the bass player's gig. Well, not only that, not after Scott LaFaro.

Can't we just tell you the end of the story and let you figure out what happened before you got here? Can't we skip all those transitions? Let go unsaid what everyone already understands? Scott LaFaro skipped ahead to the good parts, the musical dog-eared pages.

It's not like LaFaro can't walk. Ah, there's another jazz term with obvious metaphorical possibilities—the bassist playing those quarter notes in a line, four to a bar, setting the tension of the music in motion. La Faro could play those quarter notes till the cows came. Till Houdini reappeared chain-free and breathing like a mortal.

He could swing hard. The multiple articulated note—playing C C C C C—the string of half notes where quarter notes would have been played by others, the suspension that delayed gratification, as in good sex—all those ways he could swing without obviously swinging. Abstract. Abstracted.

His phrasing is unexpected, the lines like so many boxcars, but then the strange uncoupling of melody from bar line. That's like holding hands with a goddess. It's implying things you don't need to say, if you can hear.

We don't need a photograph of that night that LaFaro must have sat in with Bill Evans the first time. We almost don't need to read about it.

He would push Evans: man, you're fucking up the music. Cut out "the stuff" it's wrecking your life. And your playing. Don t give me this shit about transcendence and pain. Give me the space to play. I don't care if it's feeling or not, I don't care if it's a fucking sandwich.

To which Evans might have said, as he did eventually say, "Actually, I'm not interested in Zen that much, as a philosophy, or in joining any movements. I don't pretend to understand it. I just find it comforting. And very similar to jazz .... Like jazz, you can't explain it to anyone without losing the experience. That's why it bugs me when people try to analyze jazz as an intellectual theorem. It's not. It's feeling."

When Scott LaFaro died, in one of those car wrecks that killed more jazz musicians than dope ever did, Bill Evans must have gone into an odd-shaped room and never come out again except for food and water, and that only occasionally. He must have never played any note the way he would have played it otherwise. He must have taken no whole, real comfort in any good thing, not even music.

Publishers' Weekly Review, Bill Evans: How My Heart Sings, by Peter Pettinger

"Pettinger dispenses with personal insights to such a degree that his book becomes more critical discography than biography . . . Intimates of Evans aren't described physically or characterized emotionally but are simply wrung dry of their musical content then pushed offstage. Interviews with contemporaries do provide memories of Evans, but they are often banal. In relating a life filled with romantic disappointment, extreme drug abuse and assorted illnesses that contributed to his early death in 1980, Pettinger paints only a pallid portrait of the man behind the music.

"In the end, fans of Evans's music may be left cold."

(Are we left so because Pettinger was himself a concert pianist and more interested in Evans' music than his life? Is that in turn because Evans' music was great and his life, however burdened by pathos, was just another life among the billions?

Is biography tyranny?

Who is any of us?)

1. Fall 1973: Tells his wife Ellaine that he's leaving her, probably because she couldn't bear children, in order to marry a woman he's recently met. After he leaves for California and the woman he would marry, Ellaine throws herself in front of a subway train in New York. His manager arrives to identify the body.

2. Late 1971: Gary McFarland, 38, vibraphonist, collaborator. He, along with a friend, drank cocktails into which liquid methadone had been poured. Fatal heart attack. Both men died. Details remain unclear.

3. April 1979: Harry L. Evans, brother, schizophrenic. Self-inflicted gunshot.

4. September 15, 1980: Bill Evans, 50. Hepatitis. Liver failure. A lifetime of drug use. Malnutrition.

5. July 6, 1961: Scott La Faro, 25, bassist. Car accident.

6. August 23, 1998: Peter Pettinger, 42, pianist, Bill Evans biographer. Died just before his book on Evans was released.

7. "Every day you wake in pain like death"

8. "Many clubs pay more attention to their trash cans than the house piano"

Larry Bunker, drummer: "I worked with him for a year and a half, and I really tried to get to know the man. And he would not have it. ... He'd sit and we'd hang, and pretty soon his eyes would glaze over. Then he'd take a paper napkin, draw a music staff on it, and start writing twelve tone rows—which, along with anagrams, was one of his favorite little mind recreations."

From an interview: "Do you like people?"

"Yes, but I don t seem to communicate with them very well."

Is it important to communicate with people?"

"I dedicate my life to it."

"But sometimes in concerts or in clubs you fail to. ... Does that disturb you?"

December 31, 2012. My Interview With Bill Evans, In Which He Responds To My Question "Why Did You Behave The Way You Did Your Whole Life?"

what do you mean why what do you mean behave this suggests choice when we're busy making choices like what to play and what's going to happen next it's tempting then to look beyond what's true or might be

I don't know man I just didn't want to hang around that long and have everyone get tired there's beauty and then there's everything else and if you're interested in beauty then some of those day to day things eating sleeping keeping a schedule are going to fall away I'm not saying this is a good thing it worked for me though some people might say it hasn't

Sometimes I wonder

what thoughts, what feelings he knew

as he was leaving.

Tell me what you remember

poor cold, silent autumn moon.

Kyogoku Tamekane (Sam Hamill, tr.)

My CD player has been fried, casualty of a power surge brought on by a faulty ballast in an ancient fluorescent light fixture in the basement. Or so the electrician said. I'm embarrassed that two months go by before I try to turn on the CD player and get nothing. How can two months go by where I'm not listening to anything but classical music on public radio? My router and modem were fried, too, and I realized that within a few seconds. Given this, what is essential, according to me?

Perhaps turntables. With no working CD player in my home office now, I'm listening to vinyl for the first time in months or years. My LPs are mostly jazz albums I collected during college up until the advent of cassette, maybe ten years of penny pinching and used record stores, unearthing the occasional gem.

One of the only Bill Evans I have from those days is a rare reissue, "newly discovered tapes," that kind of thing, something I bought as late as '82 or '83: California Here I Come. Even Larry, my Bill Evans-worshipping piano player, has never heard of it. The title tune is hardly an Evans standard, but much of the rest of the double issue is mainstream Bill: "Polka Dots and Moonbeams,""Emily,""Very Early,""Stella by Starlight."

The recording pairs Bill with his Kind of Blue drummer, Philly Joe Jones (the one who, in the fifties, had introduced Evans to heroin).

I set the old turntable in motion. It starts spinning slowly and then builds up steam to about a standard 33 1/3. The first thing I hear is, of course, vinyl: its gray sound, its muted blues and shorn highs. I adjust the balance of the speakers, try boosting the bass, then the treble. I try getting more of everything.

I'm reminded how the first CDs sounded so cold to us: good for classical music, but definitely not right for jazz, I was not the only one to think. Now vinyl is retro and back in style for twenty-somethings: its warmth, its evening of colors and articulation, its gauze or mesh over the midrange. But vinyl no longer sounds like real life to me— sun through clouds. So has real life changed or have I?

"Turn Out the Stars": Bill Evans' phrases are constructed to be broken into their logical and extra-logical parts. After the head, shards of melody lay across the canvas. We're told that a Bill Evans improvisation is a matter of ultimate preparation, music of the highest level, something he could turn on like a spigot. Maybe it's the left hand that seals the agreement with those who listen. No, if I single out the left hand, it means nothing without the theme and variation he plays in the right. Any given phrase he improvises is the logical sequel to the phrases before it, and leads to the phrase that follows. But perhaps that's true of any good player.

And there is form over form, layer over layer: a descending line in one chorus picks up a simpler version of the same notes from the chorus before. Great tonal memory must be as keen as a dog's sense of smell.

Time is not a watch on a wrist. It's not "kept" by the bass or drums, like a lover in a garret, hidden away from the world. Time is malleable, gains and falls back like flowing water. But not so flowery as that. Time, the beat, is the cruel master. Some art is a piece of time carved out.

(If you're among the majority of people on the planet who don't listen to jazz and have never heard of Bill Evans, you could have skipped the preceding passage. But I decided not to tell you that until now).

A True Story

"He once showed up for a gig with his right arm virtually useless. He had hit a nerve and temporarily disabled it while shooting heroin. He performed a full week's engagement at the Vanguard virtually one-handed, a morbid spectacle that drew other pianists to watch. He pulled it off, too, thanks in large measure to his virtuoso pedal technique. According to one bassist in the audience, 'if you looked away, you couldn't tell anything was wrong.'"—Victor Verney

"You don't understand. It's like death and transfiguration. . . . Each day becomes all of life in microcosm"

Now what can I do?

My writing hand in a cast

is useless—

can't manipulate chopsticks

can't even wipe my ass!

Socho (Sam Hamill, tr.)

The Japanese

His Wife: "He believed that there were many wonderful venues all over the world. I think above all he loved the Japanese audiences. Whenever a great piano was provided, he was normally ecstatic."

"There is a Japanese visual art in which the artist is forced to be spontaneous. He must paint on a thin stretched parchment with a special brush and black water paint in such a way that an unnatural or interrupted stroke will destroy the line or break through the parchment. Erasures or changes are impossible. . . .

"The resulting pictures lack the complex composition and textures of ordinary painting, but it is said that those who see well find something captured that escapes explanation….”

Lost

On September 16, 1980, I wrote a poem about Bill Evans and his influence on my musician friends and me. The poem began, "We said it always quickly like one word: billevans." The first line was perfect iambic pentameter, in a fourteen-line "free verse sonnet."

The poem went on to say that while other famous jazz artists were "Miles" or "Trane," billevans was always referred to by his full name—never "Evans" or "Bill." Then about line 9 of the poem, the trumpet player on a gig with me turns and asks me, "Hey, did you hear billevans died."

Though I’ve looked hard for it, I can't find a copy of my poem about billevans.

Later, I wrote another poem about billevans which I included in my second collection. Previously, I had tried to publish that poem in literary journals, but it was rejected fifteen times. I keep records of that.

A gloss of that new billevans poem would say that it's better to fail beautifully than to succeed in a way that is basically untrue. Others might summarize the poem differently, however.

Of all my work, this poem is my piano player Larry's favorite poem. Of course, he never saw the poem that was lost. Almost no one did.

His Death

Coughing up blood, he complained of drowning. He lost consciousness in the car and his drummer carried him into the hospital.

Bill Evans: A Fiction in Monologue

It's the scale of everything that moves me the most, man. (lights a cigarette) Little streets, little houses, little shops and restaurants with little plates of food in them. And then the plastic food labeled in the windows. All the cars there are white, did you know that? It's like, why would you want to step out of line to own something else?

The whole of the culture seems the opposite of spontaneous, and you don't lose face in front of your neighbor and your neighbor won't lose face in front of you. If you think of it, why not? Why shouldn't we each have our secrets, and within each secret is a thousand unknowns, and they're wrapped in nori and put on a plate: perfect presentation. What's really true, what's really felt, is so far within that it couldn't withstand the light of day Even in a gray city. Tokyo. Yokohama. Dim lights in front of the club or off stage. Shards of light in the alleyway, the little streets, the little buildings. The scale.

On Audiences

"Some people just wanna be hit over the head and, you know, if then they [get] hit hard enough maybe they'll feel something. . . . But some people want to get inside of something and discover, maybe, more richness. And I think it will always be the same; they're not going to be the great percentage of the people. A great percentage of the people don't want a challenge. They want something to be done to them. . . . But there'll always be maybe 15 percent. . . that desire something more, and they'll search it out. . . and that's where art is."

Visit the Bill Evans Archives

"Over 1000+ pages of materials, bound into four massive compendiums, now available by appointment. Handwritten music notation, leadsheets, personal letters & postcards, notes, art, scribblings, and more. Find out who the person behind the music really was, and why he made the choices he did, both musically and for his life.

"$100 Access for One Day"

Who Owns the Art?

In addition to Ken Burns' documentary and companion coffee table book ($45, available online for $14.78, used from $0.39, plus shipping), the filmmaker has released a series of audio recordings of jazz greats titled with his name first, followed by the name of the performer featured on that disc, Ken Burns Miles Davis, Ken Burns Louis Armstrong, and so on. The compilation of these CDs is titled Ken Burns Jazz: The Story of American Music.

I guess we are to read the titles in the way we read Boswell's Johnson or Sandburg's Lincoln. I suspect, too, that the publishers rightly intuited that the words "Ken Burns" in the title would sell more copies than the word "jazz."

Jazz is a popular music that's not very popular. That much, in their research, the producers of Ken Burns Jazz had learned.

I once heard a panel discussion in which a group of documentary filmmakers complained about how much precious grant money Ken Burns has tied up.

Bill Evans never got a grant. There is no record that he ever applied for one.

A True Story

My old friend the jazz pianist Lyle Mays tells a story something like this. He is a college student playing at a jazz festival in 1975 with a trio from North Texas State University—which is the Harvard of jazz, as anyone in the business knows. Guitarist Pat Metheny, already a professional, is also on the bill, and he and Mays meet at this venue and will hook up in a couple of years in a musical partnership that continues to this day.

One of the judges for the festival small group competition is Bill Evans. The panel of judges named Lyle's band Outstanding Combo at the festival. On his comment sheet, Evans had left the numerical scoring and written evaluation sections blank, and written instead only three words:

"See you around."

On Audiences

"Sometimes we're really on and it doesn't feel like the people really understand what we're doing; other times, people applaud wildly after a tune when I didn't really think much was going on at all."

Should anyone ever fail this beautifully again, promise me

your late conversion won't keep you

from at least

sending word—that someone

once again

hasn't wasted life

on certainty.

Heroin, counterpoint,

Ravel, cocaine:

When he got into something

he really got into it.

It seems too much

to deny a man

slumped forehead to the keys

and their impossible jagged line

like black and white starlight,

his right arm limp with dead nerves,

while the left hand turns out the stars.

The shirt someone buttoned for him,

cigarettes on spring days,

the background chatter that wasn't there. Isn't.

How long it takes to die this way

when it rains outside, and within.

I suppose when the wind behaves,

the waves take note.

I'll hear that someone

came through the revolving door

again into

the shapeless dark

and began to play.

Some Sources

How My Heart Sings, Peter Pettinger. Kind of Blue: The Making of the Miles Davis Masterpiece, Ashley Kahn. Kind of Blue liner notes (Bill Evans). Turn Out the Stars liner notes (Bob Blumenthal and Harold Danko). The Best of Bill Evans Live liner notes, Tim Nolan. "The Two Brothers as I Knew Them: Harry and Bill Evans," Pat Evans. "Bill Evans in Paris with Gene Lees," Steven Cerra. Review of How My Heart Sings, Publisher's Weekly. Bill Evans Trio: The Oslo Concerts (film). "On Ken Burns' Jazz Documentary and Bill Evans," Jan Stevens. "Bill Evans: Time Remembered," Jean-Louis Ginibre. Stompin at the Terrace Ballroom, Philip Bryant. "Bill Evans" (poem), Richard Terrill. The Essential Haiku, edited by Robert Haas. "Artist Profiles: Bill Evans," Joel Simpson, allaboutjazz. com. Meet Me at Jim dr Andy's: Jazz Musicians and Their World, Gene Lees. "Pianist Bill Evans and You, Professor," Jacques Berlinerblau. Bill Evans Archives (website). Alone (Again) liner notes, John L. Wasserman. "A Review of How My Heart Sings," Victor Verney, compulsivereader. com. "Interview with Nennette Evans," Jan Stevens, billevanswebpages.com. "It Was Just One Afternoon in a Jazz Club Forty Years Ago," Adam Gopnik, billevanswebpages.com. All The Things You Are: The Life of Tony Bennett, David Evanier.

Not long before his death Bill tried to reach Tony Bennett on the phone. They had made two recordings together when the singer was in the midst of his own drug problem and had lost his big studio recording contract.

Finally, after nights of trying to get through, Bill succeeded.

"Just keep going after beauty and truth," he told the singer. There was a certain desperation in his voice. In weeks, he was dead.

Years before, he wrote a letter to his friend Gene Lees explaining that he started using heroin back in the fifties because he didn't think he deserved the fame and recognition that was his after playing with Miles Davis on Kind of Blue. "If people didn't believe I was a bum, I was determined to prove it."

His Two-Week Method of Learning Music

"Since there are only 12 notes in music, you can spend one day a week to learn everything there is about each note, and still take Sundays off."

JFK would be 95. Bobbie would be 86. Charlie Parker would be 92. John Belushi would be 63. Janis Joplin, 69. Sylvia Plath, 79. Miles Davis, 86.

Maybe we simply couldn't imagine them as elderly, as having trouble getting around, as not being ahead of where we are.

Scott LaFaro would be 78. Bill Evans would be 83. It's the jazz uber story. Car accidents.

Narcotics. A life compressed. Among the jazz musicians who left life young, few were the picture of youth at the end of the years they had.

Or maybe everyone's got the whole thing wrong. Maybe what truth there was—that which preceded myth, anthologies, compilations, "desiccated biographies," commercial appropriations, neglect and deification, related tyrannies— maybe that bit of truth was lost like a scrap of paper filed away in a box then moved from apartment to house to house over a lifetime of new residences, then discarded by someone who had to clean up the mess of boxes after the pack rat passed on. Maybe, all accounts to the contrary, Bill Evans' inner life was an act of tremendous ego, of supreme selfishness—first to sacrifice one's years practicing sixteen hours a day. Then at the end to close the door to the toilet and sit there in a cocaine haze. More than one critic notes that the fire and drive of his last quartet may have been due not as much to his being energized by youthful partners on bass and drums, as by his replacing heroin with cocaine as his drug of choice. From downer to upper. From cover it over to burn it down.

We'd like to imagine a truth more lyrical than any of these. We'd like to think we each could make something beautiful, something that might last, some one thing, some art. And think that someone who could make beautiful things again and again, each better than our best effort, that that person could not possibly be cognizant of his capacity ("he lacked self-confidence"). To be aware of that gift would be like living in a body the entire surface of which was as sensitive as the fingertips, the genitals, the tongue. So hard and not worth it to be a genius, the rest of us have to think, and to be so driven and obsessed to use that genius, seeing so clearly that talent is nothing unless put into play, that life does not progress as much as it lists moments. To see that one life among the billions, despite what the good-hearted say, cannot matter much. But music can. Sometimes.

Last Words to a Journalist Requesting an Interview, Copenhagen 1980

"We have to run to catch a plane.... I have to go. Didnt you have a chance in all of that? I really have to go, I’m sorry."

START here (again)

18. he never recorded country and western or contemporary Christian music

19. "I think he was out of his body when he played"

20. he wasn't an ascetic

21. his wife: "He hated electric guitars. He hated rock. Period"

22. in the '60s a record producer suggested he make a rock album

23. he was not a member of an organized religion, wasn't an activist in any political movement, nor a member of any fraternal society such as the Masons or the Rotary

24. in the middle of the night, Miles Davis would often call to go bowling

25. he could swing harder than some people gave him credit for

26. he was sometimes unaware of how his words and actions would be felt by those around him, including those close to him

27. he never performed at football, baseball, or soccer stadia

28. "Ladies and gentlemen — I don’t feel like playing tonight. Can you understand that?" '

29. when he died, he was as old as he was going to get

30. he sometimes must have been aware how his words and actions would be felt by those around him

"See you around. "

.jpg)