© -Steven Cerra , copyright protected; all rights reserved.

[The editorial staff at JazzProfiles posted the following as a five-part feature in early 2009. Ever since that time, we’ve wondered how it might read as a single essay. With your kind indulgence, we thought we’d give it a try.]

Mentioning my name in the same context as that of Gene Lees , the late, esteemed Jazz writer, might be the height of presumption on my part, but in doing so in this instance, I mean it only as the basis for a speculative empathy that he and I might have in common.

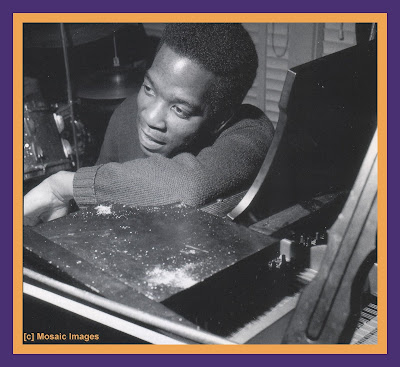

Because of his close and enduring friendship with Bill Evans, the legendary Jazz pianist, many of us in the Jazz World waited patiently for what could only be termed the definitive work on Bill and his music as provided by Gene Lees , the cardinal writer on the subject of Jazz in the second half of the 20th century.

And yet, while there is an exquisite chapter by Gene about Bill entitled “The Poet” in his compilation, Meet Me at Jim and Andy’s, Mr. Lees never ventured forth with the long-awaited, full-length treatment on Evans.

Wth his passing in April, 2010, the reasons why Gene’s book on Bill Evans never materialized can only be surmised, but perhaps, and this is mere conjecture on my part, Gene was too close to his subject.

Also, he may have been overwhelmed by the immensity of dealing with the size of the footprint that Bill left on Jazz. Or, it may be, again a supposition on my part, that the loss of his friend was still something that weighed heavily upon him making the task of writing objectively about Evans a difficult one.

If the latter was the case, then I know well the feeling as I have been stymied in publishing something – anything – about Victor Feldman, my friend and mentor, since his death in May, 1987.

And while I keep doing interviews with people who knew Victor and amassing information about him from a variety of sources, I just haven’t been able to organize, what has, by now, grown into a sizeable mass of information, and issue forth with a piece about this immensely talented musician and wonderful human being.

That is, until now.

Three [3] factors prompted me to at least start the process of talking about Victor and his music with this feature.

First, I came across this comment from Peter Keepnews in his 12/28/1997 New York Times review of Ted Gioia ’s History of Jazz: [New York: Oxford University Press, 1997]:

“Those of us who have tried writing about Jazz know what a daunting challenge it can be to do it well. Expressing an opinion about a given musician or recording is easy; explaining what exactly it is that makes that musician or recording worth caring about is not.”

Second, I re-read the following qualification or caution from the author Philip Caputo who states:

“No writer ever truly succeeds. The disparity between the work conceived and the work completed is always too great and the writer merely achieves an acceptable level of failure.”

So having been reassured by the likes of Messer’s Keepnews and Caputo that what I have been attempting to do is difficult, but that I should do it anyway, my third motivation to finally write something about Victor Feldman came in the form of an e-mail from Mrs. Shelly Manne in which she asked: “Have you done that piece on Victor, yet?”

The Manne’s and the Feldman’s were great friends and out of respect for that friendship, and my own friendship with Victor, what follows is an initial piece about the advent of Victor Feldman on the American Jazz scene.

In looking back over all of the research that I have accumulated concerning Victor, it is amazing to note how many Jazz musicians held this quiet and unobtrusive man in such high esteem. And, given such a collective high regard, one cannot help but be as puzzled as Mrs. Shelly Manne when she commented to me: “Why is it that no one ever talks about him? It’s such a shame. He was a terrific musician and Shelly had so much respect and admiration for him.”

So let’s rectify this glaring omission and talk about Victor Stanley Feldman, born in London , England April 7, 1934 , for as Joe Quinn commented in his liner notes to Vic Feldman on Vibes – Mode LP/V.S.O.P. #13 CD] :

“By any standard of comparison, Vic Feldman is an extraordinary musician.”

Victor Feldman was a prodigiously talented musician, arranger and composer whose time in the Jazz spotlight lasted only a relatively short while. He left it for a financially lucrative career in the recording studios and the world of popular music, including writing for Joni Mitchell and Steely Dan, primarily between the years 1965-85.

Because of his amazing displays of virtuosity on drums at a very young age he achieved early notoriety in his native England Los Angeles

Listening [and watching] Victor Feldman play drums was a jaw-dropping experience, especially if you were a drummer and knew how difficult it was to play at Victor’s very high level of preciseness, power and speed. Stan Levey, Shelly Manne, Colin Bailey and John Guerin knew what very few others in the US Jazz world were even aware of and that was that Victor Feldman was one of the best drummers on the planet – bar none.

Ever the showman, Woody Herman knew what he had in Victor and would come to feature him nightly in an extended drum solo on “Mambo the Most.”

Thanks to a friend in New Zealand, who has a fantastic knowledge of Jazz in general and Woody Herman in particular, I was able to hear Victor play this feature on a 1956 radio broadcast by the band at the New Lagoon in Salt Lake City. I would venture to say that if you gave this track to 10 drummers as a “blindfold test” that 9 out of 10 would swear they were listening to one of Buddy Rich’s extended, solo masterpieces.

Unlike Rich, who had never studied formally, Victor had studied drums in London March 20, 1958 issue of Downbeat, “… that God-given talent.”

According to a 1999 e-mail that I received from Mr. Lawrence Woolf, who went to school with both Victor and tenor saxophonist Tubby Hayes:

“We all attended school together in the North London suburb of Edgware. Victor was only a fair student. He was more interested in tapping on his desk and humming along. Sometimes he got ‘balled out’ over it by teachers and students alike!

His Uncle, Max Bacon, a standup comic and quite good drummer was teaching Victor to play drums which he took to ‘like water.’ Vic would talk and think about nothing else but ‘Being the best drummer in the world.’

To cut a long story short, he became a child drum prodigy and played the Music Halls across England BBC radio. …

In my opinion Victor Feldman [rest in piece] was one of the most underestimated musician’s ever born.”

Victor’s drumming mates in England such as Allan Ganley and Tony Crombie, shown in this photograph taken while Victor was making one of his appearances at Ronnie Scott’s club at Number 39 Gerrard Street in London, knew of his protean prowess on the instrument, and another drummer, Ronnie Stephenson, who worked with Victor at Ronnie’s club in 1965 said of him: “He could just take your breath away with his combination of speed and power. You just had to put it out of your mind to be able to play drums behind him.”

Victor’s voyage of discovery to the U.S.A. June 6, 1963 edition of Downbeat.

During the interview with John that makes up most of the article, Victorrecounted thatit was during his tenure with Ronnie Scott’s band that he made the crucial decision to emigrate to the United States

The year was 1953 and by then, Victor had become a multi-instrumentalist drummer, pianist vibist, having studied the latter in London London

In July, 1954, at the beginning of a tour of Europe , the Woody Herman Band shared a bill with Ronnie Scott’s group at the U.S. Air Force base at Scunthorpe , England Gene Lees in his Leader of the Band: The Life of Woody Herman [New York

Victor shared in the Tynan Downbeat article that while at Scunthorpe :

“’I got to know some of the Herman sideman including Al Porcino [lead trumpet], Chuck Flores [drummer], Bill Perkins [tenor sax], Nat Pierce [pianist] and Cy Touff [bass trumpet].’ Their brief encounter with the young Englishman was probably forgotten by most of them, but later, in New York

In October, 1955, Feldman made the plunge and sailed on the French liner Liberte’ landing in New York

Shortly thereafter, Cy and Nat Pierce took Victor to a band rehearsal where Woody offered him the vibes position in the band previously held by Red Norvo, Marjorie Hymans, Terry Gibbs and Milt Jackson. [Lees, p. 219]

Thus began another chapter in Victor’s “love-hate relationship” with going on the road for as he explained to Tynan:

“I didn’t want to go on the road. Even as great a feeling as it was – to go with Woody’s band – I just didn’t want to go on the road, because I know how my physical and mental capabilities work on the road. It’s a bit too rough for the kind of personality I am. But naturally I just couldn’t turn it down. … Woody was so nice and everything. He made me feel so relaxed.”

Before leaving with Woody, Victor had made a prior arrangement to record an album for Keynote Records and set about making arrangements for the date. Bassist Bill Crow tells the tale of this ill-fated Feldman, Keystone recording session in his book From Birdland to Broadway [New York

“One night [in 1955] a young man sat at the Hickory Bill Crow on bass and Joe Morello on drums]. When our set was finished, he introduced himself as Victor Feldman. The talented English vibraphonist had just arrived in New York

‘I’m doing an album for Keynote,’ Victor told us, ‘and I’d like you guys to do it with me. I’ve already sort of promised it to Ken ny Clarke, so I’ll have him do the first date and Joe the second. I’ve got Hank Jones on piano.

Both dates went beautifully. Victor had written some attractive tunes, and he and Hank hit it off together right away. We couldn’t have felt more comfortable if we’d been playing together for years. Victor was glad to have the recording finished before he left town to join Woody Herman’s band.

The next time I ran into Vic, he told a sad story. The producer at Keynote had decided to delay releasing the album, hoping Victor would become famous with Woody. But the next Keystone project ran over budget, and when he needed to raise some cash, the producer sold Victor’s master tapes to Teddy Reig at Roost Records. Vic came back to New York, discovered what happened, and called Reig to find out when he planned to release the album.

‘Just as soon as Keystone sends me the tape,’ said Reig.

Vic called Keystone to ask when this would take place, and was told the tape had already been sent. A search of both record companies offices failed to locate the tape, and as far as I know it was never found. It may still be lying in a storeroom somewhere, or it may have been destroyed.

Since Keystone announced the album when we did the date, it was listed in Down Beatin their “Things to Come” column, and that information found its way into the Bruyninckx discography, but now that Vic and Ken ny are both gone, that music exists as a lovely resonance in the memories of Joe, Hank and myself.”

Kindly responding to an inquiry from me in March, 1997, bassist Bill Crow had this to say about Victor’s approach to Jazz:

“I just liked everything I heard him play, and I liked the physical feeling of playing with him. He generated a good strong swing and communicated his enthusiasm for music in a very generous and enjoyable way. He chose good chord sequences, had a strong ear for the original melody, and knew that jazz is about having fun with music. I wish I’d had more chances to play with him.”

While on the Herman band, in addition to the players that he had met in London, also on Woody’s band were pianist Vince Guaraldi, tenor man Bob Hardaway and bassist Monty Budwig, all from California and all of whom would ultimately play a role in Victor’s decision to stay on the West Coast after his playing days with Woody’s band were over.

After nine months on the road, Woody disbanded and took a small group into Las Vegas California San Francisco New York

When Woody’s small band disbanded, Victor returned to England for a short vacation, but by then his mind way made up and, although he came back to the states to do a second nine-month stint with Woody, he ultimately left the band and at the “ripe old age” of 23, opted to come to Los Angeles and take up residence in 1957.

As Tynan describes: “Before locating a cheap flat in Hollywood

Victor went on to say: ‘I met Leroy Vinnegar and played with him. And I met Carl Perkins. Carl showed me a lot. I learned a lot just from watching him and going around to his house. He didn’t know the name of any chord, hardly; he didn’t know much more than what a C minor or a C major was, or a major or minor chord. But the way he voiced his chords – I never heard anything like it in my life.’”

Victor arranged four of the seven tunes on Leroy Walks! [Contemporary S-7542; OJCCD-160-2] and since the other three tunes on the album were “head” arrangements, to essentially arrange all the tunes and play on one’s very first recording in Los Angeles is a rather impressive way to make one’s mark in new, musical surroundings. Nat Hentoff concluded his liner notes comments about him by declaring: “He is a flowing swinger with a forcefully inventive conception.”

Victor also toured briefly with clarinetist Buddy De Franco’s quartet in 1957 [the gig that actually brought him to L.A.] and although they didn’t record together at that time, when in 1964 Buddy wanted to do an album playing primarily the bass clarinet for Vee Jay he asked Victor to fly into Chicago for the recording. The result was Blues Bag [Vee Jay VJS-2506] on which Victor plays piano and he and Buddy are joined by Victor Sproles on bass, Art Blakey on drums and, on two tracks, Lee Morgan on trumpet and Curtis Fuller on trombone.

Five of the seven compositions follow a standard blues pattern including Monk’s Straight, No Chaser, Coltrane’s Cousin Mary and Ornette Coleman’s Blues Connotation. The other two, Kush by Dizzy Gillespie and Rain Dance by Victor are according to Leonard Feather“unmistakably related to the blues if only by indirection.” Leonard commented further about Rain Dance:

“This unusually attractive Victor Feldman composition is the only track in the album for which, in the ensemble passages only, De Franco reverts to soprano clarinet. Blended with Morgan’s trumpet and Fuller’s trombone, this gives the ensemble a highly engaging sound in Feldman’s ingenious voicings. The chorus is oddly constructed, consisting mainly of two 16-bar stanzas followed by a six-measure linking interlude. Morgan and Fuller are both featured in solos on the tune’s beguiling changes.”

However, it would be unfair to paint a picture of Victor landing in Los Angeles England United States

[As an aside, Victor’s rather extensive recording career in London United States

Suite Sixteen: The Music of Victor Feldman [Contemporary C-3541; OJCCD-1768-2] contains a sampling of Victor’s work done in England United States

As Lester Koenig, Contemporary Records owner and the producer of this album commented in his liner notes:

“The album is an authentic musical portrait of Victor Feldman at the peak of his career in England

As composed and arranged by Victor, the fiery and intricate big band tracks alone such as Cabaletto and Maenya are worth “the price of admission” for this album.

What becomes very obvious to the listener about “The Music of Victor Feldman” on Suite Sixteen and ultimately on all of his recordings is everything that is significant about it has to do with rhythm, or to paraphrase Bill Crow : “he generates a good strong swing and I liked the physical feeling of playing with him.”

The significance of rhythm in Jazz cannot be overemphasized.

As Wynton Marsalis stressed in his interview with Ben Sidran published in Talking Jazz: An Oral History in 43 Jazz Conversations [New York

“… harmonyis not the key to our music. Harmony is used in motion. And motion is rhythm. And rhythm is the most important aspect. I mean everything is important. But whenever you find a valid rhythmic innovation, the music changes. … You change the rhythm, you change the music.”

Perhaps it was the fact that he started in music as a drummer and continued on as a vibraphonist and ultimately as a pianist – two other percussive instruments - but there was a distinct physicality to Victor’s music. Victor’s orientation is always rhythmic first which perhaps also explains why drummers such as Shelly Manne, Stan Levey and Frank Butler loved to work with him.

1957 was a turning point in Victor’s career for a Victor explains it: “I was very fortunate in ending up at The Lighthouse in Hermosa Beach , CA

In a conversation I had with Howard Rumsey in 1999 at a Los Angeles Jazz Institute commemorating the 50th anniversary of Jazz at The Lighthouse, Howard remembers Victor approaching him about his need for a vibes player. Howard replied that “I could really use a piano player.”

At the same event, I asked drummer Stan Levey, who was a member of the Lighthouse All-Stars when Victor came on the band for his recollection of how it all began. Stan said that “When he auditioned for the job, he was barely able to gig as a Jazz pianist. He rented a piano and woodsheded [practiced] for two weeks. When he came on the gig, his piano playing was right there.”

In the Tynan interview, Victor talked about his time at the club: “I ended up working at the Lighthouse for eighteen months. … The Lighthouse was what set me on my feet because it was a steady gig. Howard was very nice to me, and it was a ball playing with Rosolino and Levey and Conte. Bob Cooper, too. It was a very relaxed atmosphere.”

In a concerted effort to flunk out of high school, I started attending the Lighthouse regularly a short time after Victor joined the All-Stars, primarily on Sundays when they would play from 2 PM to 2 AM , but also on the occasional weeknight.

As an aspiring Jazz drummer, it was late on one of the sparsely attended weeknights that I summoned the courage to go up to Stan Levey, always an imposing figure, to ask him a question about some aspect of the mechanics of playing the instrument.

The band members usually congregated along the back wall of the club between sets. When I approached Stan and asked my question he replied: “ you don’t wanna talk to me about that sh**; I’m self-taught. The guy you want to talk to is sitting over there [nodding toward Victor sitting alone at an adjoining table]. He even knows the names of all the drum rudiments!”

At the time, I had no idea that Victor played drums. I soon found out as he thoroughly answered my question as well as demonstrating the answer. Shortly thereafter, Victor Feldman agreed to offer me lessons.

In an interview with he and fellow guitarist Pat Martino conducted by Jim Macnie for the March 1997 issue of Downbeat Les Paul commented: “We learn so much if we’re wise enough or lucky enough to listen to the right players.” I certainly “got lucky” in meeting Victor when I did as he proved to be a kind and gentle mentor from whom “I learned so much.”

During his year-and-a-half stay at The Lighthouse, Victor began getting more and more calls for a variety of recording dates including the previously mentioned Vic Feldmanon Vibes [Mode LP 120; V.S.O.P. #13 CD], the first recording date under his own name since arriving in Los Angeles

Significantly, this date would include Carl Perkins on piano, from whom Victor had learned so much about chord voicings [the method in which notes are played together in particular, vertical structures], in a rhythm section completed by Leroy Vinnegar on bass and Stan Levey on drums.

As his front-line mates Victor chose Frank Rosolino on trombone and Harold Land on tenor saxophone. The group performs six tunes, four of which are Victor’s originals including his striking Evening in Paris, a tune that was to become a fixture in the Lighthouse All-Stars repertoire.

Victor preferred the hard driving and “harder” sound that Rosolino projected and he was absolutely enamored with the big, bluesy “Texas-tenor” style of Land. In combination, Rosolino and Land produced what Leonard Feather described as “a more vigorous California

Interestingly, with the exception of Victor replacing Carl Perkins on piano, this same group would re-unite as a quintet a year later under Frank Rosolino’s leadership for an album that was eventually released under the title of Free For All [Specialty SP-2161; OJCCD-1763-2].

1958 opened with Victor going into a Contemporary Records studio along with Scott LaFaro on bass and Stan Levey on drums to record The Arrival of Victor Feldman [Contemporary S7549; OJCCD-268-2], a recording that was to become in many ways the most noteworthy of his career.

As Victor recounts in Nat Hentoff’s liner notes: “It was shortly after he began working at the Lighthouse that Victor, Scott LaFaro and Stan Levey started playing together, first at the club, and then “we felt so good we played on our own.”

As taken from my interview with him at the 50th Anniversary Lighthouse celebration, Stan Levey commented about this recording: “The group we had with Scotty was like a moment-in-time and the ‘Arrival album’ is a musical treasure. Victor was an unbelievable player in every way; just listen to him, he was perfection.”

Hentoff goes on to say in his liner notes: “The general consensus of appraisal among those American jazzmen who have heard him is that Victor’s future will be sizeable and rewarding. It seems to me that … Victor has … [a] naturally organic conception, emotional resources, idiomatic heat and growing individuality.”

In their 6thEdition of The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD, Richard Cook and Brian Morton offer this evaluation of the “Arrival” album:

“Arrival is a marvelous record, completed just after Victor had settled in Los Angeles

Victor, Scotty and Stan were recorded by Howard Rumsey later in September, 1958 in a performance at The Lighthouse along with tenor saxophonist, Richie Kamuca. Consisting of two tracks – Sonny Rollins’ Paul’s Pal[misnamed It Could Happen to You on the record] and John Coltrane’s Bass Blues, - these two tracks were issued along with three cuts by trumpeter Joe Gordon performing with Shelly Manne and His Men at the Lighthouse in 1960 as West Coast Days: Joe Gordon & Scott LaFaro [Fresh Sound FSCD-1030]. One can only hope that more of the music from this great trio will one day surface from The Lighthouse vault.

I recall Victor commenting about this trio in retrospect by saying: “Scotty and I were so young in those days and so caught up in the music that we had no idea of what we couldn’t do. Stan [Levey] had such great time and laid it down so hard that it made it possible for Scotty to free up the time, something that he really went on to develop later with Bill Evans. But Stan and I were such straight-ahead players that we couldn’t wait for him to start playing in 4/4 and away from the freer feeling. He really set the instrument on a different course”

This recollection harkens back to Wynton Marsalis’ point: “Change the rhythm and you change the music.”

Howard Rumsey, The leader of the Lighthouse All-Stars and the bassist in the group described Scott LaFaro’s accomplishment this way: “His use of two base voices, a falsetto-like solo sound and a full-bodied, well-rounded walking tone timbre, made him an inspiration to most jazz players that heard him or followed him.” [quoted in the insert notes to West Coast Days: Joe Gordon & Scott LaFaro].

Unfortunately, a trio that Stan Levey described as “a moment in time” disbanded when Scotty left for New York in 1959 and Victor decided to move on to other things and to leave The Lighthouse All-Stars. As he told John Tynan, the reason for this decision was “because I felt I had been in one place too long; musically you can stay in one place just so long.”

However, Victor’s availability would prove portentous as it would make it possible for him to participate as a temporary replacement for pianist Russ Freeman in Shelly Manne’s group during its September, 1959 two week engagement at Guido Cacianti’s Blackhawk at the corner of Turk & Hyde in San Francisco , CA

One of my earliest impressions of Victor centered around how the All-Stars radiated a crackling, propulsive drive underscored by Stan Levey’s impeccable time coupled with Victor’s percussive and hard-driving piano “comping” [musician-speak for “accompaniment”]. This was a characteristic of Victor’s playing that always impressed me – his drive was formidable as can be heard in any variety of settings and I think it was largely responsible for transforming Shelly Manne’s group in the seminal sessions recorded and issued by Contemporary from the group’s Blackhawk appearances [Contemporary S7577-7580; OJCCD-656-660-2].

Let’s “talk” further about these classic recordings and Victor’s role in helping to make them so singular from the perspective of three authorities on West Coast Jazz: Ted Gioia , author of West Coast Jazz: Modern Jazz in California, 1945-1960 [New York: Oxford, 1992], Bob Gordon , author of Jazz West Coast: The Los Angeles Jazz Scene of the 1950s [London: Quartet, 1990], and Lester Koenig, the owner of Contemporary Records who produced these in-performance albums and wrote their liner notes.

As Gioia describes [pp.279-280]:

“The final newcomer [Shelly reorganized The Men in 1959 adding Joe Gordon on trumpet and Richie Kamuca on tenor sax] to the Manne group for the Blackhawk session was an unexpected last-minute substitution. Manne regular pianist Russ Freeman had left on a road trip with Benny Goodman around the time of the San Francisco

More familiar to some listeners as a vibes player, Feldman made clear his piano credentials during the Blackhawk gig – his ensuing engagement with Cannonball Adderley is reported to be the result of the latter’s favorable response to the Manne recordings. …

Feldman … never gained the jazz reputation he deserved, although he eventually established himself as one of the premier studio musicians in Southern California …. His piano playing was anything but the limited ‘two-fingered’ approach of many doubling vibraphonists and instead revealed a rich harmonic texture, a strong percussive element, and a good sense of space and melodic development.”

Or as Bob Gordon shares [pp.206-207]:

“There was a bit of apprehension about Feldman, who was in effect learning the book on the job, but he fitted in from the start. … Cannonball Adderley was so impressed by Victor’s playing on the [Blackhawk] sides he hired Feldman for his own group.”

And lastly, Les Koenig’s insert note comments:

“Those who know Victor Feldman as a vibes player will be startled to discover that on the Blackhawk set he plays piano only. Whether he is comping for the horns, or soloing, his invention, drive, and basic jazz feeling put him in the front rank of today’s jazz pianists.”

I think the world of Russ Freeman, Shelly’s regular pianist and, having lived for a number of years within a 10 minute drive to Shelly’s Hollywood , CA

Maybe it was because they were trying to keep warm during the damp and cold San Francisco

Victor could have that effect on people. He played drums from the piano stool and booted the band along.

Some years later when I asked Shelly about these dates, he said: “Well, I can’t say it was like having another drummer on these sessions as we both know that he is another one and what a bad-a** drummer he can be. The feeling is just different with Vic; it’s like looking into a musical mirror only your hearing it, not seeing it.”

I also asked Victor about my observation and he laughed and said” “You have to remember that I had only been playing piano on a regular basis for less than two years when I made the Blackhawk gig. I didn’t have the facility yet so I would have to fall back on chorded rhythmic phrases, particularly at the end of a long solo. After a bit, I got the feeling that Shelly liked me to bring this into my solos so he could do some things behind it

But what I remember most about that gig was that everybody had a good time. We couldn’t wait for it to start each night.”

Victor Feldman – Part 2: Adderley, Feldman, Hayes & Jones [not a law firm]

© -Steven Cerra , copyright protected; all rights reserved.

as to the title of this piece, I thought about calling it “Part 2: The Cannonball Years,” but since Victor was only with Cannonball for less than a full year, I thought that might be overstating things a bit!

I lived in San Francisco March 4, 1999 , a typical, foggy San Francisco

We got together in one of the city’s many restaurants serving Asian food, this one with the innocuous name of “The Beach House,” located next to the now defunct Coronet Theater near the corner of Geary and Arguello.

Orrin had very kindly consented to be interviewed about Victor Feldman, particularly about Victor’s time with Cannonball Adderley’s quintet and Victor’s association with Riverside Records which Orrin co-owned with Bill Grauer.

Although they have since become legendary, at the time, The Blackhawk gig [with which we closed Part 1] with Shelly’s group amounted to a couple of weeks of work for Victor plus some out-of-town expenses.

Upon returning to Los Angeles Colin Bailey .

There was also the matter of what to do about an attractive woman named “Marilyn” [the former Marilyn McGrath] whom he had met during a local gig. Nine months after they met, they married in 1960.

As Victor recounted to John Tynan in his June 6, 1963 Downbeat article:

“I decided all of a sudden that I’d like to take her to England Paris Ken ny Clarke on a Dinah Shore

Cannonball had called me about a month before I went back to England Riverside S-9355; LandmarkLCD-1304-2].

While we were in England

Let’s pick up my 1999 interview with Orrin Keepnews at the point of the Julian Cannonball Adderley “Poll Winners” album that was recorded in San Francisco

According to Orrin, he and Cannonball had decided to use guitarist Wes Montgomery and bassist Ray Brown on the album and this led them to think further about “unusual instrumentation.” Although there was some talk about Les McCann, the feeling was that he was primarily blues player, but more importantly, Cannonball just didn’t want to use a piano player.The rest of the conversation went as described by Orrin in the album’s liner notes:

“With all the established musicians (including the regular Adderley drummer, Louis Hayes) living fully up to expectations, the surprise element was provided by the then-unknown Victor Feldman.

In view of the unconventional feeling of guitar and bass, Cannon had wanted something less routine than just a piano player. West Coast friends recommended a highly skilled young L.A. studio vibraphonist, recently arrived from England; figuring that we only need him for coloration, we took a chance and invited him up [to San Francisco North Beach

At rehearsal, Victor sat down at the piano to demonstrate a couple of his compositions. I can still clearly visualize all of us standing there, open-mouthed and thunderstruck, as we listened to a totally unexpected swinging and funky playing of this very white young Britisher.

Finally one of us, struck by an apparent facial resemblance, expressed our mutual amazement. “How can the same man,” I asked, “look like Leonard Feather and sound like Wynton Kelly?”

As you will note, two of Feldman’s tunes [The Chant and Azul Serape] were inserted into the repertoire; and within just a couple of months he had been hired as the Adderley quintet’s regular pianist.”

As was the case at this time, all vibraharpists were quite unfairly cast in the shadow of Milt Jackson, and while, Milt is a super player, Victor’s vibes solo on Frank Loesser’s Never Will I Marry on the Poll Winnersis four choruses of the most sophisticated vibes playing your ever likely to hear. Not only that, it doesn’t contain one Milt Jackson “lick” nor one repeated phrase.

In the flood of admiration for Milt Jackson’s playing as a vibist, most of it deserving but some of it simply fawning, by the New York-based Jazz writers, Victor’s development of his own, singular approach to playing the instrument was never given the attention it deserved. Victor was always very respectful of Milt and his contributions, but what he plays during the Never Will I Marry improvisations are inventions that go well-beyond Jackson

Mike Hennessey in his insert notes to Dynavibes: The Jeff Hamilton Trio featuring Frits Landesbergen [Mons MR 874-794] comments that, Landesbergen, the excellent Dutch drummer who plays vibes on this album, “ … also has a high regard for the late Victor Feldman. He says: ‘Victor was a great, all-round musician who played piano, vibes and drums and who was a fine composer and arranger. I think his vibraphone playing was more advanced harmonically than most other players.”

Victor had one of the most astute harmonic minds in Jazz, a fact that would be exemplified in his ability to re-harmonize something as pedestrian as Basin Street Blues, as well as, to infuse interesting harmonies with advanced rhythmic structures to create tunes like Joshua and Seven Steps to Heaven.

Returning to the Keepnews interview, Orrin implied that Victor's hiring by Cannonball validated him on the New York Jazz scene. For example, it made possible Victor’s own release on Riverside of Merry Olde Soul, as well as, his appearance on other Riverside album's such as those by James Clay and Sam Jones, who even named one of his Riverside dates after Victor's tune - "The Chant." On this album, Victor shared principal arranging responsibility with Jimmy Heath.

The driving force behind much of this activity was Cannonball who had become a kind of ex officio artists & repertoire man for Orrin at Cannonball. One of the reasons for Cannonball's status in this regard according to Orrin was that, unlike many musicians, "Cannonball was extremely articulate and therefore able to express his ideas very clearly. Cannonball's approval of Victor's playing and his work gained for him instant acceptance with me and some of the giants of the music including Miles Davis who had tremendous respect for Cannon."

Orrin further reflected that had Victor remained in the New York area, the natural course of events would have been such that he would have made a major mark on the Jazz scene. As it was, Miles Davis looked him up when he went to "the Coast" in 1963 and the result was the Seven Steps to Heaven album.

However, the rigors of traveling which impacted adversely on his recent marriage to Marilyn and the monetary lure of the Hollywood studios proved too great and he returned to Los Angeles

Since we all live the consequences of our choices, instead of dwelling on “what-might-have-been,” let’s spend time on the recordings that Victor did make while with Cannonball, in concert with others and those he made as a leader as this is a wonderfully productive period in his career.

In their 1963 interview, Victor shared with John Tynan: “Actually, my first gig with Adderley’s band was the 1960 Monterey Jazz Festival [held in September of every year]. I remember, we played ‘Dis Here’ [Cannonball’s earliest “hit recording”] and I got lost on it.”

Ironically, when Victor began his recorded tenure with Cannonball the following month, it landed him right back at his old stomping grounds – The Lighthouse in Hermosa Beach , CA

“This was Victor’s first recording with Cannonball’s quintet … and the zest he adds to an already highly-charged unit is certainly among the highlights here.”

This is not hyperbole on Orrin’s part as Victor’s presence is felt throughout this album be it in the form of the I-dare-you-not-to-tap-your-foot during his five solo choruses on Jimmy Heath’s blues tribute to bassist big brother, Percy, entitled Big P, or be it in the form of his intriguing original composition Exodus with its modal vamp and its circle of fifths bridge and which also has Julian saying “Yeah, Vic” to his brilliantly constructed solo on the tune, or be it in the form of his masterful comping on What is This Thing Called Love?, theevergreen that closes out the album [a classic example of Victor “drumming” from the piano chair].

And on this album, it’s easy to discern that one year and one month after the Blackhawk sessions that he recorded with Shelly Manne’s quintet, Victor’s piano chops had come a long way as the improvised lines just flow from his right hand. As is exemplified on Azul Serape, the other original by Victor that Cannonball included in this album, this time the block chord rhythmic riffs are interspersed throughout Vic’s solo and the “tag” that ends the tune instead of being relied on to complete a solo. Victor has more stamina and control while at the keyboard and there’s little doubt that both of these skills would continue to grow as a result of his time with Cannon.

While in town for The Lighthouse appearance, Victor participated on James Clay’s A Double Dose of Soul [Riverside RLP-9349; OJCCD-1790-2]. Recorded on October 11, 1960, it was part of the “Cannonball Adderley Presentation series” and as such was an example of what Orrin meant when he talked about the effects of Cannonball’s patronage on Victor’s career.

Vic, who always had a knack for writing tunes that were rhythmically and harmonically interesting to play on [and plenty of them, too] contributed New Delhi

Soon after their stint at The Lighthouse, Cannonball’s quintet embarked for a tour of Europe as the group was becoming something of a phenomenon in world-wide Jazz coteries, in no small part due to Riverside’s earlier albums featuring the group, most especially the In San Francisco album Riverside RLP-1157; OJCCD-035-2].

The band traveled as part of a Norman Granz organized Jazz at the Philharmonic package from which two albums were produced on Norman

Unfortunately, and perhaps due to contractual consideration, the music from the group’s JATP 1960 European appearances was not released until 25 years after it was recorded.

The first album is entitled What is This Thing Called Soul [Pablo Live 2308-238; OJCCD-801-2] and the tracks were recorded in performance in Paris , France Stockholm , Sweden ABA

When the LP version was released in 1984, I distinctly remember that this was not a good period for the Feldman Family as Marilyn had been diagnosed with the disease that would claim her life the following year.

I brought the album over to his house and we had a laugh over the tempo for both the version of Jimmy Heath’s Big P and the standard What is This Thing Called Love? as they are reflective of a Jazz truism to wit: the more a group performs a tune, the faster it will play it. Victor chuckled and said: “You should have heard ‘em by the end of the tour; I thought that Louis Hayes’s right arm was going to fall to the floor.”

Once again these tracks demonstrate what a complete pianist Victor was becoming and going on the band with Cannonball had so much to do with this for as Victor commented: “It was the best thing that could have happened to me because Julian set such a high standard and I wanted to do well to support the faith that he had in bringing me on the band. At first, I didn’t play vibes at all and this helped me in bringing my piano chops up. But you know how it is. There is no substitute for working regularly with a band like Cannonball’s and what it does for your playing.”

By any measurable standard, Victor’s piano playing has improved dramatically on these recordings. On both Azul Serape and What is Thing Called Love, Victor rolls out a much more complete piano technique replete with rapid-fire, single note phrasing, playing across bar lines and block chording that is willing interspersed throughout a solo instead of relied on to complete one.

Although Victor was gone by then, Norman Granz’s “Jazz at The Philharmonic” would issue more from Cannonball’s 1960 European tour with the 1997 release of The Cannonball Adderley Quintet: Paris-1960 [Pablo PACD-5303-2]. It contains what I consider to be one of the best solos by Victor ever recorded with Cannon’s group and if you don’t believe me just listen to Julian in the background during Victor’s six choruses on Nat Adderley’s Work Song, a 16-bar blues.

In his insert notes to the recording, Chris Sheridan, Cannonball’s biographer and the manager of a website devoted to Cannonball comments:

“In the rhythm section, British pianist/vibist Victor Feldman had joined a few months earlier, bringing an articulate single-noted and block-chording style that was closer to Wynton Kelly than his predecessor, Bobby Timmons. The Adderleys were particularly taken with his compositions, which, like the hot gospelling, ‘The Chant,’ fattened the band repertoire…. Remarking on his pianist’s Englishness, Mr. Adderley once observed: ‘He isn’t supposed to have this kind of soul because it’s the other kind of soul.’”

While with Cannonball and living in New York Riverside

As Orrin Keepnews recalled: “The was no question of using Sam Jones and Louis Hayes on it as by now they had formed quite a rhythm section; I think I was the one who suggested Hank Jones on piano for one session to free up Vic to play vibes on three tracks.”

“There are not many albums where all the tracks deserve some comment. Here, each one has something to offer and bears mention. Various influences on Feldman’s style are in evidence, yet because of his own strong personality, he does not emerge as a mere eclectic. There is a great difference between intelligent absorption and imitation.”

Although all of the nine tracks are the album show off various aspects of Victor’s developing style and technique, here are Ira’s comments about four of the tunes. I would only add that Victor’s vibes solo on The Man I Love is one for the ages – an absolute marvel of building tension and release brought about by a musician with an incredible sense of syncopated rhythm, a well-developed feeling for melody and an ever deepening knowledge of harmony.

“Victor opens on piano with ‘For Dancers Only,” a happy, swinging interpretation of the Sy Oliver tune immortalized by the old Jimmie Lunceford band. His chording seems to show a Red Garland influence. Sam Jones has a strong solo and the integration of the trio is perfect: they literally dance. ‘Lisa’ is a collaboration between Feldman and Torrie Zito; its minor changes cast a reflective but Victor’s touch here on vibes still swings. …

On ‘The Man I Love’ (the only no-piano vibes number), Feldman starts out with a light touch similar to his work on ‘Lisa.’ Then he intensifies into a more percussive attack that wails along Jacksonian lines, in a spirit that may put you in mind of Milt’s solo on Miles Davis’ famous version of the tune, but without copying Jackson. He builds and builds into highly-charged exchanges with Hayes before sliding into a lyrical tag.

‘Bloke’s Blues’ is a rolling line that I find somewhat reminiscent of Hampton Hawes. There is an easy natural swing and much rhythmic variety in Feldman’s single line. His feeling is never forced.”

“In this album, his first for ‘Riverside’ as a leader, the spotlight is really on Victor. His piano and vibes are both given wide exposure, and there is a substantial taste of his talents as a composer (of blues and ballads in particular). He proves more than equal to the task of filing a large amount of space with music that consistently sustains interest.”

Later in January 1961, participated in bassist Sam Jones’ big band session based around the Cannonball Adderley quintet of the time. The album took its name from Victor’s oft-played original The Chant [Riverside RLP-9358; OJCCD-1839] and to add honor upon distinction, Victor was asked by Sam Jones, the album’s principal, to prepare some of the arrangements along with Jimmy Heath! Victor shares piano duties on the album with Wynton Kelly and takes the solos on Benny Golson’s Blues on Down and Rudy Stephenson’s Off-Color.

While living in New York

“I was getting that old feeling back again about being on the road, which I’d been on since I was 15. Although I was having a ball playing, there was this tug of war going on with me. Had I been single, I would have stayed maybe a little bit longer.”

Victor returned to Hollywood and experienced the “out-of-sight, out-of-mind’” dynamic as far as the contractors who hire musicians for studio gigs are concerned.

However, no sooner had he found some work in the studios and had his trio performing at The Scene on the Sunset Strip in Hollywood, than a call came in from Peggy Lee to join her for her first European tour. Since the gig included six weeks in England before heading to the French Riviera for 10 days and Stan Levey on drums, Victor was back on the road again.

The beginning of 1962 found Victor back in the studios with a flood of calls from both Hank Mancini and Marty Paich, among others, and also increasing his activity with his trio including making two recordings during the year.

The first of these was The Jazz Version of Stop the World I Want to Get Off [World Pacific WP-1807]. As Victor told Howard Lucraft, who authored the liner notes:

“I’ve been approached about doing a show album many times. However, this is the first time I made one because this is the first show that has had tunes that make good jazz vehicles.

I tried to make the arrangements as interesting as I could without cluttering the three of us, so that we could relax in our improvising.”

Bob Whitlock was once again on bass because as Victor put it very directly: “I always have Bob with my trio; his greatest asset is his extremely broad knowledge of music.”

Somewhat of a surprise to some, although not to others who knew Victor’s preferences for hard-driving drummers, Lawrence Marable made the date on drums because according to Victor: “Lawrence is one of the finest drummers in the world. I love his time feeling. I love his solos. When he and I play together we reach terrific peaks of excitement. Lawrence has the greatest intuition.”

The nearest thing to a Philly Jo Jones style of drumming on the West Coast, Lawrence, much like Frank Butler [and, of course, Philly], really emphasized the snare drum in his solos. Whether these were fours, eights or entire choruses, everything came off the snare and Lawrence Colin Bailey who loved to put emphasis on the snare during his solos; Colin also has incredible snare to bass drum coordination.

As show tune recordings go, this is a remarkably good, musical album, no doubt because Victor always put so much thought into arrangements for his trio. The album has the added bonus of Victor playing vibes while accompanying himself on piano which he does via “over-dub.” As Victor comments to Lucraft: “Actually, I like playing vibes this way best, for recording.”

Perhaps it is the presence of Marable, but Victor “comes out smoking” on this album and plays throughout with an air of assurance and forceful determination. You can tell that he has reached a point where what he’s hearing in his head can immediately be transported to his hands, especially on piano. Howard Lucraft expresses this point similarly:

“In the earlier days of his musical career in America, Feldman was, perforce, somewhat eclectic. Today, he has his own distinctive, driving, agile and assured style. His unique, contrasted chordal work and his compelling, chromatic phrases are arresting features.”

As the title indicates, this recording is an admixture of movie themes and songs associated with movies, although Victor manages to put in another version of his original – New Delhi.

Three different groups each make up four tracks and these include Buddy Collette [ts/fl], Victor [v/p], Leroy Vinnegar [b], Ron Jefferson [d]; Clifford Scott [ts/fl], Victor [v/p], Laurindo Almeida [g], Al McKibbon [b], Frank Guerrero [percussion]; Nino Tempo [ts], Victor [p], Bob Whitlock [b], Colin Bailey [d].

Although the twelve tracks averaging about three minutes each was primarily aimed at commercial radio play and mass market distribution, there is some very good music on this recording including Buddy Colette’s take on Victor’s New Delhi, the bossa nova version of Anna from the movie The Rose Tattoo for which actress Anna Magnani won the Academy Award and the Nino Tempo version of Walk on the Wild Side with the Feldman-Whitlock-Bailey trio.

As someone who was an indirect beneficiary of the “overage,” I can personally testify to the fact that during 1962, Victor’s studio activity increased dramatically that is until, as Victor described it, “… the temptation to travel reappeared.” This time it took the form of Benny Goodman’s tour of the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics May 28, 1962 . According to Ross Firestone, Swing, Swing, Swing: The Life & Times of Benny Goodman [New York

“The rhythm section consisted of John Bunch on piano, Turk van Lake on guitar, Bill Crow on bass and Mel Lewis on drums. Teddy Wilson and the vibraphonist Victor Feldman were to be featured on the small group numbers.” [p.409].

Victor returned from the Goodman tour of the USSR, but this time he literally picked up where he left off in terms of studio work as there was so much of it and he was such an accomplished reader, both as a pianist/vibist and as an overall percussionist. He was also dependable, prompt and courteous, not to mentioned very well-liked by the coterie of contractors and first-call studio players.

Also upon his return from the Soviet Union, Victor signed an exclusive recording contract with Fred Astaire’s Ava records.

The first project that Victor completed for the label was to record three “Jazz Impressions of … “ tracks with Bob Whitlock [b] and Colin Bailey [d] to augment the release of the original sound track by Mark Lawrence to the then highly acclaimed film – David & Lisa: An Unusual Love Story [Ava-AS-21].

But while at Ava records, Victor was at work preparing a real gem of a recording based on compositions that he and Leonard Feather had come across during his trip to Russia

Released in 1963, The Victor Feldman All-Stars Play Soviet Jazz Themes [Ava/As 19] is comprised of two recording sessions involving three Soviet Jazz originals, both involving the rhythm section of Bob Whitlock on bass and Frank Butler on drums. The first took place on October 26, 1962 with Victor on vibes, Nat Adderley on cornet, Harold Land on tenor saxophone and Joe Zawinul on piano and the second session was done on November 12, 1962 with Victor on piano and vibes, Herb Ellis on guitar, Carmel Jones on trumpet and Harold Land once again on tenor.

Here are Leonard Feather’s original liner notes that offer a perspective on both the Cold War politics of the time as well as on the Soviet Jazz musicians and their music which Victor represented on this recording.

“There has never been n album quite like this before in the annals of recorded jazz.

The very existence of Soviet jazz, of artists who could play or write it, was virtually unknown outside the USSR Soviet Union and let it be bruited around that they were really jazz musicians. The resultant impromptu concerts led them to discover that a cadre of young musicians existed whose interest in the American jazz world, bolstered by Voice of America

Three years later, on a more official and far more broadly publicized basis, Benny Goodman's band, the first American jazz orchestra of modem times to play the Soviet Union (under U.S. State Department auspices) opened May 30, 1962, at the Central Army Sports Arena in Moscow. On this tour the brilliant and versatile Victor Feldman played vibraphone in the small combo numbers; and most valuably, during the six weeks of the tour, he gained a fairly broad picture of the musical life of the Russians, the Georgians and other citizens of this endless land.

I was lucky enough to be in Moscow Leningrad

The aims of Victor Feldman's LP are, first, to compensate for this omission; second, to provide a program of modem jazz by superior soloists with plenty of blowing room; third, to point up the similarities, rather than the differences, that can be found in a comparison of jazz composition as it is conceived in Moscow, Tbilisi or Leningrad vis-À-vis New York, Chicago or Los Angeles.

Soon after arriving in Moscow, we found out that homegrown jazz, supposedly taboo in the USSR, not only wasn't underground or outlawed as had long been believed, but was actually flourishing on a modest scale. It even had young. growing outlets at a Moscow jazz Club, where students earnestly discuss the latest news about John Coltrane or Ornette Coleman, and at a couple of Youth Cafés, where music by the new Soviet jazz wave is often heard live.

Writing in Down Beat about a visit to the Café Aelita. I observed: "It is the closest Moscow comes to a night club … serves only wine, closes at 11 p.m., and is decorated in a style &at might be called Shoddy Modern, though radical by Moscow standards ... the shocker was the trumpet player, Andre Towmosian. who is 19 but looks 14, plays with the maturity of a long-schooled musician, though in jazz he is self-taught."

I learned that Towmosian was acclaimed in the fourth annual Jazz festival at Tartu , Estonia Leningrad

University Jazz Festival; and one of the souvenirs I brought home

was a tape, given me in Leningrad

Also on tape were some of the compositions of Gennadi (Charlie) Golstain, the alto saxophonist and arranger whose apartment I visited in Leningrad

side on the wall of his living room I noticed adjacent photographs of two men: Nikolai Lenin and Julian (Cannonball) Adderley.

Golstain's tapes featured him with a combo similar to the Feldman group an these sides, but he works regularly with a large modern orchestra headed by Yusef Weinstain and writes most of the band's book. He is a soloist of considerable passion,

as yet incompletely disciplined and subject to multiple influences, but his dedication is beyond cavil and his writing shows an intelligent absorption of the right influences.

“Several of the fellows in Benny's band jammed a couple of times with Gennadi at our hotel, the Astoria in Leningrad," Victor recalls, "and some of us, including Phil Woods, played with him at the University., He was eager for knowledge and information, like so many of the musicians we met."

Goldstain is the composer of three of the lines in this set - Blue Church Blues, Madrigal, and Gennadi - as well as the arranger. or virtual re-composer, of the folk song Polyushko Polye. (For those curious about the first title, it should be pointed out that the church Gennadi had in mind was not Russian Orthodox, but probably Southern Baptist.)

Also represented here is a young arranging student named Givi Gachechiladze, the composer of "Vic." He lives in Kiev Tbilisi

The rapport that grew between the Soviet musicians and the Goodman sidemen showed in microcosm the kind of amity that could exist on all social levels if meetings were possible between men and women of the two countries who have common interests. All of us who tasted the hospitality of these devoted jazz musicians and students were touched by their sincerity, their lack of political animosity (many seemed totally apolitical), and their obvious desire to discuss things shared rather than differences.

The young musicians like Towmosian, Golstain, Constantin Nosvo and Gachechiladze, none beyond their 20s and many in their teens. have not yet earned substantial recognition in their own country. It is ironic that this is the first album featuring Soviet jazz compositions that has ever been recorded, not merely in the U.S.A.

The group selected for these two sessions is in itself further reflection of the "United Notions" character of jazz. Here are the works of writers in the Soviet Union, performed in America by a group under the leadership of Victor Stanley Feldman, who came to this country in 1955, at the age of 21, from his native London (the native city also of this writer, who helped organize the sessions); and on the tracks that feature Feldman's vines the piano is taken over by Joe Zawinul, a superb modern pianist who was born in Vienna and did not arrive here until 1 959, Zawinul works regularly with the sextet of Cannonball, whose brother Nat is heard on three tracks (Ritual, Madrigal, Blue Church Blues.)

Harold Land and Herb Ellis, both from Texas, and Carmell Jones of Kansas are well known to the Soviet insiders, as are drummer Frank Butler Kansas City

Certainly these sides, because of the historic precedent they set and because of the esteem in which Feldman and his colleagues are held in what used to be thought of as the borsch and balalaika belt, will be among the most desirable collectors'

items when the first copies reach the Soviet Union . For listeners in this country it is to be hoped that they will help reinforce a concept not of the jazz-as-propaganda-weapon cliché, but the unifying image of this music gathering strength and growing stature as part of a single world.”

It is a great disappointment to those who are familiar with the music on this album that it has never been issued as a commercial CD and, in general, received a wider recognition as the music on it is simply superb by any standard of comparison.

Victor Feldman – Part 3: Miles & Beyond

© -Steven Cerra , copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“His keyboard technique is above reproach and is matched by his brilliance on vibes and drums; his knowledge of rhythms and meters, and the possibilities inherent in combining melodic lines with percussion expressions, greatly expounds the sounds of any group within which he works.” [Philip Elwood, The San Francisco

These eloquently phrased words of high praise for Victor Feldman were shared by no less a Jazz luminary than Miles Davis, who sought out Victor to perform and record with him during his April 1963 sojourn to the Left Coast.

Ironically, Victor closed his June 1963 Downbeat interview by sharing the following anecdote with John Tynan:

“The other day I was fortunate enough to record with Miles Davis. When I was 16, I went to Paris Paris

The details for Miles’ trip to California New York

It seems as though the first quarter of 1963 was A Time of Troubles for Miles when, for a variety of reasons, pianist Wynton Kelly and bassist Paul Chambers, and ultimately, drummer Jimmy Cobb, too, left Miles. Miles claims these departures came about abruptly. They asserted that they gave him sufficient notice, but that he refused to accept the fact that they wanted to leave.

Whatever the actual reasons for this falling out are beyond the scope of this piece, but the fact of their departure meant that Miles had to hastily put together a rhythm section for upcoming appearances including those at the Jazz Workshop in San Francisco Los Angeles

Miles always had a tremendous respect for Cannonball Adderley and it was he who suggested to Miles that he might turn to Victor and see if he was available to help out during these West Coast gigs.

I recalling Victor sharing that when the call came in from Miles’ booking agent, he was recording a Viceroy cigarette [do they still make these?] radio jungle [with lots of bombastic percussion], composed no less by Marty Paich, at the RCA sound studios on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood.

During the rehearsal, someone from the recording engineer’s booth came down and passed Victor a message. He excused himself to make the call and he came back later with a “cat-that-swallowed-the-canary” look that had everyone curious.

With the expensive recording studio meter running, everyone had to wait until they were packing up before he told them the good news that Miles wanted him to come up to San Francisco for the Jazz Workshop gig.

The bad news was that Victor was on the Hollywood ABC TV staff orchestra at the time and was forced to tell Miles that he could arrange with the show’s contractor to get a few days off “… while you try to get someone else.”

As Victor recounted in an interview with Les Tomkins while in England

“It was enjoyable, although I didn’t know any of the things we had to play. And Miles doesn’t tell you anything, which bugged me a bit. It’s inconsiderate but, on the other hand, maybe it was a compliment and he figured I could pick up very quick. Everyone seemed to be happy, anyhow. Then a few weeks later Miles came out to Los Angeles

In what Jack Chambers refers to as “the Hollywoodballad sessions,” Victor [piano] would join with Frank Butler [drums] along with Miles, George Coleman [tenor sax] and Ron Carter on bass on April 16, 1963 at the Columbia Hollywood Studios to record four ballads: I Fall in Love Too Easily, Baby Won’t You Please Come Home, So Near So Far and Basin Street Blues.

Although Joshua and Seven Steps to Heaven, two originals by Victor were recorded the following day, Miles re-recorded them a month later as features for Herbie Hancock [piano] and Tony Williams [drums]. These two tunes plus three of the ballads were released as Seven Steps to Heaven [Columbia CL 2501; Columbia/Legacy CK 48827]. [Although re-united on the CD version, So Near So Far wasn’t originally issued until 1981 on Columbia KC2 36472.]

As a point in passing, it might be interesting to reflect that as the composer to Seven Steps to Heaven, Victor Feldman created the vehicle that introduced to the world the drumming brilliance of Tony Williams.

In the concluding paragraph to her article on the piano prodigy, Matt Savage, that appeared in the October 29, 2008 edition of The Wall Street Journal, Corina da Fonseca-Williams states that: “’Seven Steps to Heaven’ was a pivotal recording in the history of jazz… [and] the title tune is a piece that insists on the primacy of harmony.”

Although co-credited to Miles, I know for a fact that the true, primary and sole author of Seven Steps to Heaven and the advanced harmonies that it employs was Victor Feldman as I heard him play it many times in a variety of trio settings [including one with Frank Butler] before he recorded it with Miles.

Keeping the melody of Seven Steps to Heaven in mind, one could re-read the Philip Elwood quotation that opens this piece [repeated below] and easily come to the conclusion that Victor, not Miles, had the predilections of mind necessary to compose such a tune.

“His keyboard technique is above reproach and is matched by his brilliance on vibes and drums; his knowledge of rhythms and meters, and the possibilities inherent in combining melodic lines with percussion expressions, greatly expounds the sounds of any group within which he works.” [Philip Elwood, The San Francisco

Joshua, however, may have been more of a joint effort as Miles describes in the following from the 1969 Tomkins interview:

“Miles said: ‘Write something.’ Just like that. So I went home, messed around, and wrote ‘Joshua.’ Actually, I think I finally finished that one day prior to the recording. In between, I’d go to the hotel and we’d take the tunes that we were going to do, he’d suggest certain changes and I’d say: ‘How can that be?” But sure enough, a lot of the time what he’d suggest would turn out fine. The only thing, he’d sort of put you in a frame of mind where you really didn’t know what you were doing; you were groping. I sensed that he was looking for something, but he didn’t know how to tell me what he wanted. The feeling he gave you of searching, this finally brought out the chord structure for the arrangement. We’d been experimenting with the tune and it was: ‘Not this way – no, that way,’ until we molded it into shape.”

Basin Street Blues, one of the tunes on Seven Steps to Heaven that author Jack Chambers categorizes as one of the “Hollywood ballads,” was a traditional Jazz, 16 bar blues that Victor had been intrigued by for years. Once, when I asked him why he was so interested in the tune I remember him replying: “I just like the way it lays out [unfolds melodically] and it has such a lovely melody. I get picture in my mind of what jazz in the early days down in New Orleans

When I first heard him “fooling around with it,” Victor played it in a slow, measured manner and as a solo piece. He was also constantly taking the song’s rudimentary changes and re-harmonizing them in a manner that became increasingly stylish and more and more sophisticated over time.

It was this slow, refined version of Basin Street Blues which Victor introduced to Miles for the Seven Steps to Heaven album. Although perhaps unaware of this background, Jack Chambers alludes to it in the following excerpt from Milestones 2: The Music and Times of Miles Davis Since 1960:

“’Basin Street Blues’ written by Spencer Williams … was part of the standard repertoire of New Orleans bands in the earliest days of jazz history and subsequently passed into the repertoires of revival bands. Traditionally, it was played as a medium-tempo paean to the city that the musicians had left behind them when they moved north along the Mississippi

Davis plays it as a kind of requiem, slow and mournful, emphasizing the elements of nostalgia which in traditional versions exists only as an undertone. His deliberate, wispy tone makes a striking reinterpretation of the content of the original song.” [p. 55]

Bill Milkowski made these comments about the playing of ‘Basin Street Blues’ in the insert notes to the Seven Steps to Heaven CD:

“Miles’ melancholy muted trumpet sets a dark tone on this rendition. The combination of his velvety smooth lines alongside Feldman’s gentle touch and sparse comping recalls the intimate mood that Miles and Bill Evans had conjured up on “Blue and Green’ and ‘Flamenco Sketches’ from ‘Kind of Blues.’”

Concluding about his association with Miles in the Les Tompkins interview Victor said:

“Miles Davis brought out my creativity. Before working with him, I’d heard a lot of stories about him. But I never believe things people tell me about anybody like that.

… Everyone has a quality within themselves that’s beautiful: who are we to set up standards about how a person should act? I enjoyed playing with Miles and I enjoyed meeting him. He certainly seems to be very straightforward; he says what he wants to say. … That’s the way he plays – in a very honest way. Whenever you play with him, you get a feeling of starting afresh, and wiping the cobwebs away. He creates an atmosphere round him that helps you steer clear of clichés.

In fact he gets on my nerves sometimes, in a way, because he gets hold of a piece and wants to change it around so completely that I think he takes it too far. Then, on the other hand, maybe it’s a good thing to do that – to really tread new ground.”

Although I have emphasized Victor’s relationship with Miles to underscore his status as a major Jazz player and to reflect on what might have been, the fact was that Victor was increasingly busy in his own right on the West Coast Jazz scene before and after his time with Miles.

He had made albums as a sideman with Frank Rosolino [Turn Me Loose!, Reprise R9-6016; Collectibles COL-CD-6159], Barney Kessel [Music from “Breakfast at Tiffany’s”; Reprise R9-6019; Collectibles COL-CD-2857 ], Curtis Amy [Way Down, PJ46; released as part of the 3 CD Mosaic Select set, MS-007], and Joe Maini, [Joe Maini Memorial [Fresh Sound FSR 408], all of which were released in late 1962 prior to his April 1963 dates with Miles.

Through a family connection, I had a brief involvement with Reprise Records during its early years. As a result, I was able to attend the November, 1961 Turn Me Loose! recording session that marked Frank Rosolino’s debut as a vocalist.

I remember Frank commenting that he was so pleased that Victor could make the date which also included Chuck Berghofer on bass and Irv Cotler on drums. Frank said of Victor.

“I worked with the man for about two years and he swung his a** off every night at the Lighthouse. His comping keeps the time so alive. And his solos are always so driving and full of fresh ideas. Vic is one of the best kept secrets in LA.”

Curtis was so impressed with Victor’s work with Cannonball that he hired him for his Pacific Jazz Way

And, in May, 1963, the month after recording with Miles he was in the Columbia Hollywood studios recording with Paul Horn [Jazz Impressions of Cleopatra, Columbia CL2050] before commencing two albums with his own trio of Monty Budwig [bass] and Colin Bailey [drums] that were released on Vee Jay in 1964: Love Me With All Your Heart [VJ1096] and It’s a Wonderful World [VJS2507].

Bassist Chuck Israel, who played on the Paul Horn Cleopatra date with Victor along with Colin Bailey on drums to form the rhythm section wrote the following to me in a 1997 E-mail:

“Aside from this early association with Victor in LA, when we moved to San Francisco

Victor talked at length about his trio and his two Vee Jay recordings in an earlier interview that he gave to Les Tomkins that coincided with a February 1965 appearance at Ronnie Scott’s Club. He also had some deservedly complimentary things to say about his new “mates” in this same interview.

“I have a trio in the States consisting of Monty Budwig on bass and Colin Bailey on drums. Colin is from Swindon , England

We’ve recorded for Vee Jay, and I’m very excited about the album we did. Most of the tracks weren’t more than three or four minutes long. At one time, I never used to like making short jazz records and I still think doing so just for commercial reasons is a drag, actually. But, in another way, I find that to keep on playing a long solo, when you’ve said what you have to say – I don’t think that’s too good, either. In these albums I‘ve managed to stay away from that. I approached it from the standpoint so that we’d have some cohesion through the whole thing. To be honest about it – some of them were short because they could be made into singles, of course. But I felt it was as much of a challenge to condense what you have to say into capsule form. A few of them I didn’t allow to be cut down, because it would have lost the whole point of the piece.

I find the trio context very satisfying. I’m always looking for new tunes. I don’t find it easy finding tunes that I can mold to the way I want to play, but I’m sure there are a lot around that are suitable. The trouble is, I’ve never been one of those people – I don’t think I know the lyrics of one tune. I don’t know the authors of many tunes, I’m ashamed to say. Now it’s becoming annoying to me, because I think it would help to find new material if I knew more about what standard tunes have been written by various people. We have about 60 tunes that we play with the trio, and that’s quite a lot, really. But we need new things to rehearse. … You have to start hearing new phrases and playing in a different way.”

Leonard Feather, long a champion of Victor and his music, offered these thoughts about It’s a Wonderful World [Vee Jay VJS2507] in his liner notes to the album which was released in 1964:

“The maturing process in a musician is far easier to trace today than it was a few years ago and infinitely simpler than before the advent of LP records. Not only has the quantity of recorded output increased, but as a general rule the artist, at least if he is respected by the recording companies with whom he is associated, is granted a substantial measure of freedom in the selection and interpretation of his material.

Victor Feldman is a case in point. In the ten years since he arrived in this country, or more particularly in the eight years since he made his first album as a leader, his style both as a pianist and vibraharpist has been observable in a series of performances that offer a portrait in depth of his evolution during this period.

The setting selected by Victor for the present sides is the one that usually shows off a jazz pianist to fullest advantage, offering him as centerpiece of a trio in which bass and drums fulfill something more than a mere accompanist function. The material is a carefully selected and intelligently programmed series of standards and originals. …

In sum, these two sides offer a splendidly rounded picture of Victor Feldman as pianist, vibraharpist and combo leader. … It is Feldman music, and for anyone familiar with what these two words have meant in recent years that should be all the categorization required.”

As has been established throughout these pieces, Victor’s playing has always had a tremendous emotional impact on me. I view his solos as being beautifully crafted and usually expressed with a driving sense of swing; not that he couldn’t be lyrical as well. Usually his playing in almost any context was rhythmic and forceful or what Cook & Morton note as a “… characteristically percussive touch” in their 6th Edition of The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD.

In this same work, these authors also put forth the following observation about Victor’s playing:

“It’s an interesting aspect of his solo work that its quality seems to be in inverse proportion to its length. Feldman was a master of compression who often lost his way beyond a couple of choruses.”

Needless to say, while I would agree with their contention that “… Feldman was a master of compression,” I take serious exception to the claim that “… he often lost his way” in longer solos [a contention for which Cook & Morton offer no examples].

There are many examples of miniature masterpieces in the form of shortened solos contained in the Feldman discography and since the “master of compression” point is not in dispute, I won’t belabor it here.

But I would like to underscore its significance with the following excerpts from Gene Lees ’ interview with pianist Junior Mance that appeared in his Jazzletter [March, 1997, Vol. 16, No. 3, p. 7]. In an aside to his discussion about Mance’s time with Dizzy, Gene explained:

“Groups get hotter as the evening wears on, but Dizzy’s groups always ‘started’ hot. I once asked Dizzy how come; how did he do that. The group would swing on the first tune of the first set. I said, ‘What’s the secret?’ Dizzy said: ‘Play short tunes.’

Later in the interview with Gene, Junior comments:

“Dizzy never played more than three or four choruses; very condensed. A lot of older musicians, the old masters were the same way. … [Charlie Parker would] say, ‘Listen, if you can’t say it in three or four choruses, you’re not going to say it. Wait ‘till the next tune. … Lester Young said the same thing. Some cats would get to that fifth or sixth chorus, he’d say, ‘Save some ‘till later.’

One thing Dizzy told me when I first joined the group that really stuck with me, he said the sign of maturity in a musician was when you learned what not to play, what to leave out.”

Perhaps, Victor learned this lesson well early in his career?

Although not released until over 30 years later, the 1965 appearance at Ronnie Scott’s Club resulted in – Victor Feldman: His Own Sweet Way– and this recording offers 11 excellent examples of Victor’s skill with extended solos. And yet, even here, while the tunes may be longer in overall length and Victor may take longer solos, Victor shares the spotlight with the bassist and the drummer keeping the group ethos as paramount.

Ironically, in many ‘ways,’ this most comprehensive and expressive recording of Victor’s playing available was recorded by an amateur on a portable tape recorded! This recording is a fortunate audio documentary of The Return of the Prodigal Son – Indeed, All Hail the Conquering Hero!

What was commonplace to those of us who had occasion to hear Victor’s trio in various Los Angeles venues throughout the decade of the 1960s is captured on this recording made by combining performances that took place at Ronnie Scott’s on the evenings of February 8 and 10, 1965, respectively. The eleven tracks come together to form an almost perfect 78 minute set. It’s all here.

Victor’s original Azul Serape played as an up tempo cooker with a marvelous Latin lead-in involving four bar exchanges between Victor on piano and some expert drumming by Ronnie Stephenson. The alternating two chord tag which takes the tune out builds into an excitement that is almost palpable before Victor intrudes to introduce Rick and Ronnie to the most appreciative audience that was fortuitously at Ronnie’s to hear this glorious music first-hand.

Another Feldman original – Too Blue – was for a time was Victor’s theme song. It offers an absolutely brilliant vibes solo based on eight superbly crafted blues-inflected choruses. And, following Rick Laird’s bass solo, Victor comes back with four more choruses before taking the tune out! He must have been in the mood to play the blues as he also contributes another original blues - Alley Blues – to the set.

A Fine Romance makes an appearance as do magnificent treatments of Autumn Leaves and Swinging on a Star, all unfurled by way of medium tempo, intricate arrangements that feature extensive solos by Victor who at times, alternates between piano and vibes during the same tune adding color and depth to these performances.

The elaborate and extended solos by Victor on this album are the complete antithesis of the short track Vee Jay album that chronologically preceded it and are an example of a musician at the top of his form and who has more than adequately found his way through longer more elaborate musical formats.

Let’s close this segment on the career of Victor Feldman with excerpts from Les Tomkins liner notes to Victor Feldman: His Own Sweet Way

“Although he was only to be seen at Ronnie Scott’s club for one week – his shortest showing yet – Victor Feldman made a greater impression than ever. There was a general acknowledgement that Victor is a great in his own right. New factors of the Feldman performance: the predominance of piano, the exclusive use of arrangements. Appreciation was also voiced for the overall bass/ drums integration of Rick Laird and Ronnie Stephenson.