© -Steven Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“Mercer was a successful jazz singer with a distinctive, engaging style; he cultivated a relaxed manner of delivery, which emphasized his southern roots. He was well known for his work with Paul Whiteman (from 1932), and also sang with Frankie Trumbauer (recording in 1932), Jack Teagarden, Wingy Manone (recording in 1935,1944, and 1947), and Benny Goodman; his recording with Goodman's orchestra of Sent for You Yesterday and Here You Come Today (1939) was modeled on the famous version recorded in 1938 by Jimmy Rushing and Count Basie's orchestra. He continued to make recordings into the 1970s.”

- Samuel S. Brylawski and Warren Vache, Sr., in Barry Kernfeld, ed., The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz

When you read this piece that Gene Lees wrote as an homage to Johnny Mercer, you’ll know that you are in the presence of genius: both Mercer’s and Lees’.

June 1999

The Jazzletter

Gene Lees, editor

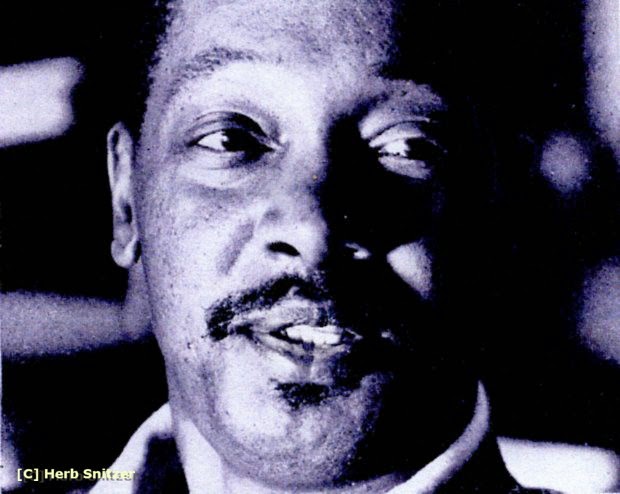

“Were Herndon Mercer alive, he would, this coming November 10, turn 90. He is buried in Savannah, Georgia, where he was born in 1909. He is the most famous native of that city, with which he never severed contact. There is a Johnny Mercer Theater in Savannah as well as a Johnny Mercer Boulevard. He was a shaping force in the American culture, both reflecting its evolving language and affecting it, but he always said that it was Savannah that shaped him.

The late Alan Jay Lerner, himself a major lyricist, considered Johnny Mercer the finest of all American lyricists. Alan Bergman who, with his wife Marilyn, constitutes one of the best lyric-writing teams the United States has known, shares that opinion. One songwriter went so far as to say that Mercer's lyric When the World Was Young is one of the finest poems in the English language. His words have passed into the common vocabulary of the United States, and indeed all the English-speaking world. He wrote 650 songs that were published, and others that he left languishing in drawers. He wrote the music to fifty-five of them. A partial list includes:

Lazybones, P.S. I Love You, Jamboree Jones, Goody Goody, I'm an Old Cowhand, Bob White, Too Marvelous for Words, We're Working Our Way through College, The Girlfriend of the Whirling Dervish, Jeepers Creepers, You Must Have Been a Beautiful Baby, Day In — Day Out, Blue Rain, And the Angels Sing, You 've Got Me This Way, I'd Know You Anywhere, This Time the Dream's on Me, Tangerine, Skylark, Dearly Beloved, You Were Never Lovelier, I'm Old Fashioned, That Old Black Magic, Hit the Road to Dreamland, One for My Baby, G.I. Jive, Dream, Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive, Let's Take the Long Way Home, Laura, Something's Gotta Give, Out of This World, Any Place I Hang My Hat Is Home, Come Rain or Come Shine, Autumn Leaves, In the Cool Cool Cool of the Evening, Moon River, and Days of Wine and Roses. All his lyrics are jewels, and more than a few of them are masterpieces. Hooray for Hollywood, a spoof of the movie industry, is one of the wittiest songs ever written.

Mercer's songs ranged in style and content from droll humor, as in The Weekend of a Private Secretary, to the painfully tender, such as My Shining Hour, perhaps the most poignant of all World War II songs. The late composer Paul Weston, who arranged the music for many of Mercer's recordings, said, "John could do more things well than any other lyricist. John had genius." He showed, as all writers do, certain predilections in subject matter. He wrote a number of songs about birds, including Skylark, Bob White, and Mister Meadowlark. Trains play a part in some of his songs, such as Laura, Blues in the Night, I Thought About You, and On the Atchison, Topeka and the Santa Fe. Afraid of airplanes, John just would not fly. He travelled only by railway or car, and, when he went overseas, by boat. He loved trains.

His imagery is unequalled in the song form. He had the most astonishing sense of the shape and sounds of words. Open vowels are very useful in the long notes that usually end phrases. For example, every singer — and John was a singer — knows that the most singable vowels in English are the oo and oh sounds. You cannot sustain consonants, except those known as the liquid consonants or semi-vowels, including m, n, l, and r. You can sing dreammmmm; you can't sing cupppppp. One of John's finest lyrics, I Remember You, is built almost entirely out of the oo, oh, and ell sounds, with brief touches on the words stars and rain. At the same time, he manages to tell a touching, even poignant, little story. It is an altogether remarkable lyric whose seeming simplicity is completely deceptive.

Was John aware of these technical considerations? His wife asked me that question after his death. I answered that I am sure he never gave them a thought; no master artist is ever consciously aware of the techniques he is using. But did he know them? Indeed. John and I used to talk about such things. But of course the technique had long since been internalized.

John was a generous man, particularly to fellow lyricists. He encouraged the careers of the lyric-writing team of Jay Livingston and Ray Evans, and indeed got them their first motion-picture assignment. He encouraged Peggy Lee to write lyrics, as well as Alan Bergman, who refers to him as "my mentor".

One of the oddest examples of his generosity is found in the 1959 song I Wanna Be Around. An Ohio woman named Sadie Vimmerstedt wrote John a letter, saying she had overheard someone say, "I wanna be around to pick up the pieces when somebody breaks your heart," and thought it was an interesting idea for a song. John wrote words and music, and gave her full fifty percent credit and half the royalties which, since the song was a hit for Tony Bennett and continues to be heard, amount to a considerable sum.

He was wont to say that the hardest part of writing a song was finding the title, for it was the key to the song.

The vast body of our best song literature came from the Broadway stage roughly between 1920 and 1955, at which time it began the long decline to its present condition. John wrote the lyrics to seven Broadway shows: Walk with Music, St. Louis Woman, which later toured Europe with an all-black cast under the title Free and Easy, Texas Li’l Darling, Top Banana, Li 'L Abner, and Foxy. But most of John's songs were either free-standing or written for movies.

Hilaire Belloc wrote, "It is the best of all trades, to make songs, and the second best to sing them." A small framed copy of that quotation hung on the wall of John's studio, thirty yards or so behind his house, snuggled in a canyon's foliage in Belair, California, next to a golf course on which deer sometimes wander. But in his heart he felt it was best to sing songs. He did it very well, and had one hit record after another.

For all his successes, he had a dark stream of melancholy in him. Anyone who knew him will tell you he was a heavy drinker, and when he was in his cups, he was a virtuoso of despair.

Some of John's songs examined his drinking, including Drinking Again and When The World Was Young, but most particularly One for My Baby, a magnificent, incredibly condensed slice-of-life short story that follows the moods of a drinker through a late evening in a bar as he confesses his life to a long-suffering bartender, progressing from sentimental self-pity at the start of the song to a kind of aggressive importance ("You may now know it, but buddy, I'm a kind of poet .... ") through to rueful apology for boring the man with his sad story. In the final version of it that John recorded, he adds a new, brilliant, self-indicting line to the old lyric: "Don't let it be said old unsteady can't carry his load."

John was Scottish on his father's side, Czech on his mother's, although it was with Scotland that he identified most strongly. At the battle of Culloden on April 16, 1746, English forces defeated a rag-tag army of Scots loyal to the Catholic Bonnie Prince Charlie. Many of the Scottish fighters were at Culloden under duress or from curiosity and some merely on romantic whim, including one Hugh Mercer; born in 1725 and not quite twenty years old at the time. Raised in largely Anglican Aberdeen, he had no especial hatred of King George II. He had just graduated from medical school, and joined the Jacobite forces as a surgeon.

After their victory, the English launched an incredibly cruel search-and-destroy campaign against Scottish civilians and anyone deemed loyal to the feckless prince. Hugh Mercer sequestered himself on the farm of relatives near Aberdeen, then in March of 1747 was able to take passage on a ship bound for Philadelphia.

Settling near Greencastle, just north of the Maryland border, Mercer resumed his profession of physician. He was urged to accept command of a local militia. He was wounded in the French and Indian wars, recovered, and served for three more years, then moved to Fredericksburg, Virginia, returning to work as a physician. His friends included George Washington, Patrick Henry, John Paul Jones, and John Marshall, future chief justice of the United States. He married Isabella Gordon, who bore him five children, the youngest named George Tennant Weedon Mercer.

Another acquaintance was one Robert Patton, one of the refugees from Scotland. Patton was an assumed name, and even his children never learned his true patronymic.

As the Revolutionary War threatened, Virginians set up a committee of public safety, mustering three regiments, one of which was commanded by Patrick Henry, a second by Hugh Merce. Mercer became a brigadier general under George Washington, and was with him when Washington led his routed army across the Delaware River in November 1776. Someone suggested a counter-attack on the 1,200 Hessian mercenaries stationed at Trenton, New Jersey. (General John Armstrong reported hearing a discussion of this plan between Washington and General Mercer. The attack was a success and the morale of Washington's forces soared. Washington then set out to take the British supply depot near Princeton. Mercer led a unit of four hundred men against a much larger unit of redcoats. There he was wounded and died on January 12, 1777. Thirty thousand mourners attended his funeral in Philadelphia.

By act of Congress, his son, Hugh Tennant Weedon Mercer, was educated without charge at Princeton University. A tradition of attending Princeton began in the family.

The Revolutionary War over, Robert Patton in his late forties married Mercer's daughter and eldest child, Ann Gordon Mercer; then twenty-eight. They had six children, among them John Mercer Patton, who became a lawyer. One of their sons was elected to Congress, and seven would fight for the Confederacy, including George Smith Patton, a colonel in the Confederate Army.

Meanwhile, George Tennant Weedon Mercer and his wife had, among their children, a boy they named Hugh Weedon Mercer, who as a cadet at West Point was a classmate of Jefferson Davis. After graduation, he was posted to Savannah, Georgia. He married the daughter of a banker named George Anderson, and they had five children, the oldest of whom was named George Anderson Mercer.

When Georgia seceded from the union, Hugh Mercer became a colonel, then a brigadier general, of the Southern forces. For most of the Civil War he was in command of Savannah, and after the war rose to a high position in the city's business and social life.

His son, George Anderson Mercer, was graduated from Princeton in 1856 and admitted to the Savannah bar in 1859. He married Ann Maury Herndon of Fredericksburg, Virginia. He too served in the Civil War, at one time under his father, and fought in many major battles.

His distant cousin, Colonel George Smith Patton, also served with distinction in the Confederate forces, as did other members of the Patton family, including Patton's brother, Hugh Patton: the name Hugh persists in both family lines. Their brother, Tazewell Patton, died of wounds suffered at Gettysburg under Pickett.

Colonel George Smith Patton too died of wounds. His widow, Sue, loaded their two children and some family belongings in a wagon and fled Union troops. They reached Woodberry Forest farm, whose main house had been damaged. A descendant, Robert H. Patton, now in his forties and living in Connecticut, wrote in his fascinating The Pattons: a Personal History of an American Family (Crown):

"There they found the corpses of two Yankee soldiers, one in the front hall, the other wedged in a second-floor window ... It was Peter and George William's task to haul the bodies to an outlying field and bury them. Peter dug the trench as George stripped the bodies of their clothing, which he then burned. Should rains ever wash out the grave and expose the bodies, the family might be accused of murdering Yankees. Naked, the bodies could never be identified."

They hid the bodies very well indeed. After the war, when the plantation had evolved into Woodberry Forest School, it became traditional knowledge that there are two soldiers buried on the grounds. But no one has ever found them. George William Patton, by the way, was only nine years old at the time of that burial.

The Pattons lived at Woodberry Forest for eighteen months, then moved to California. George William Patton changed his name to George Smith Patton, in his father's honor, and named his own son George S. Patton III. He would become, in the opinion of many historians, the most brilliant American commander of World War II. His own son, George S. Patton IV, also became a general in the U.S. Army and is now retired. His son, Robert Patton, wrote the fascinating family history.

George Anderson Mercer and his wife had seven children, five of whom survived, including a son named after himself.

This George Anderson Mercer married Mary Walter, who gave him three sons, George Mercer Jr., Walter, and Hugh. Mary died giving birth to Hugh in 1900. After a time, Mercer married his secretary, a beautiful young woman twenty years his junior named Lillian Ciucevich, whose origins were Czech. There are still Ciuceviches in the Savannah area. The family had been in America for a long time, and she was deeply Southern.

Lillian Ciucevich Mercer gave George Anderson Mercer two more children, a daughter and a son. The youngest child of the family, John Hemdon Mercer; would be known as Johnny Mercer. I have been unable to determine whether John was aware that George S. Patton was a cousin, albeit a distant one, but both men were keenly conscious of their descent from Hugh Mercer of Aberdeen, and proud of it. And Patton, it is interesting to note, loved, recited, and wrote poetry.

Henry Mancini, with whom John won two Academy Awards — for Moon River and Days of Wine and Roses— said, "Had Johnny been a military man, he would have been Patton. He used to attack a song three ways. He could hear a melody and see different angles from which to approach it, and write three different lyrics, each one valid, each one fully worked out, and each one different from the others."

Mancini knew nothing of the connection between the Mercers and the Pattons.

"Johnny was very defensive about being a Southerner and about the South," music publisher Mickey Goldsen said, recounting an incident that happened in late 1952 or early 1953, when John had long since become the most successful songwriter in America.

A movie called Ruby Gentry, released in 1953, portrayed a Southern woman of, as they used to say, easy virtue, portrayed by Jennifer Jones, who marries a wealthy man to spite the man who loves her.

Goldsen said, "Heinz Roemheld had written the score for Ruby Gentry. He said to me, 'I wrote a theme for the movie I think is great. If you can get Johnny Mercer to write the lyrics, I'll give you the publishing.'

"We got a projection room, I brought Johnny up to see the movie. They rolled the movie. It had to do with unpleasant incidents in the South, and as an overall picture, it didn't make the South look good.

"As we walked out, I said, 'That's a beautiful theme, Johnny.'

"He said, 'Yeah, but I won't do it. I don't like the way they treated the south.' And the song — " Mitchell Parish wrote the lyric "— went on to be a big hit, called Ruby. And I lost the publishing. He was very serious.

"Johnny was the most successful guy in the world. But he had a letter in his workroom. It said, 'You can't win 'em all.'"

The State of South Carolina is roughly an equilateral triangle standing on its point. Its eastern bourn is the Atlantic ocean, the western the State of Georgia. The city of Savannah lies barely over its border at the bottom point of that triangle, the two states being separated there by the Savannah River. The land is low: the entire coastal area is called the Low Country by its residents, and the cuisine reflects it, with a certain emphasis on rice, which is readily grown in its wetlands. The great salt marshes, mile on mile of reeds, green in the spring, yellow-brown in the fall, dominate the land, and the waters there yield what the locals call coon oysters, since raccoons love them, wading in search of them into the water, their paws moving zealously, leading to the myth that they wash their food, when in fact they are feeling for it with paws so filled with sensory nerves that they are almost a second set of eyes. The folks say these are the tastiest oysters in the world, and once there were, along these estuaries, countless factories where the oysters were shucked and packed in ice and shipped off to canneries. The shells grew in vast pyramid piles that were hauled away and spread on the dirt roads to be crushed under the wheels of wagons and the hooves of horses and eventually the black tires of automobiles. They made ghostly blue-white paths among the black shadows of trees on moonlit nights.

The dominant flora are palmetto and great live oak trees and tall conifers, pines mostly, with long needles or short, and all these trees are hung with gray beards of Spanish moss, an epiphytic plant almost universal in this region. Even without the history of slavery that always lies dark on this land, these trees and this moss would lend the region a certain melancholy Melancholy, of course, is the natural state of intelligent man, for we alone among the world's species know the end of our story. We keep it at bay with an affectation of optimism, although some do it with the pursuit of an avarice that precludes all compassion and for that matter rational social thought as well.

The fauna include Virginia deer; seventy-nine species of reptiles, among them twenty-three of turtles, thirteen of lizards, and three of crocodilians; and a hundred and sixty species of birds, including dove, blue heron, white ibis, and snowy egret, wading birds whose sudden flight can make the heart leap, and the bob-white, the subject of one of Johnny's songs. Swarms of mosquitoes compounded the torment of the slaves who toiled here and raised the toll of their afflictions.

Georgia actually forbade slavery when it was founded in 1733 by James Edward Oglethorpe, a young English idealist, military officer, and Member of Parliament. He landed his small colony of settlers on a bluff that rises the height of a two-story house above the Savannah River. He set up a friendship with the chief of the local Creek Indian tribe, who gave the settlers considerable help, a friendship that lasted as long as Oglethorpe remained in the New World. In time, however, the greater prosperity of the surrounding slave-holding states drew off population from Georgia and it declined, and finally the prohibition of slavery was rescinded.

Oglethorpe laid out Savannah in a grid of streets in tidy right angles on a north-northwestern slant beside the river. His precise plans established open squares every third street on the north-south lie, every fourth on the east-west lie, to be used for defense in times of hostility, as markets in peacetime. These have become small parks. The largest park, Forsyth, one of the loveliest in America, was laid out by Governor John Forsyth ten years before the Civil War.

John Herndon Mercer was born two blocks from Forsyth Park in a large white clapboard house at the intersection of Lincoln and Gwinnett Streets. Street names in Savannah predate the Civil War. The Lincoln in question is not Abraham, and Button Gwinnett was Georgia's delegate to the Continental Congress and a signer of the Declaration of Independence. He died in 1777 -— from a wound incurred in a duel — on nearby St. Catharine's, one of the many barrier islands that lie off the coast.

The house is at 226 Gwinnett. Four brick steps rise to its front porch, whose roof is upheld by four white round pillars. John's father, the second George Anderson Mercer, was graduated from the University of Georgia law school. He was an able ball player; indeed he turned down an offer from the Cincinnati Reds in order to go into practice with his father, and, later, the real estate and investment business. He was loved and admired in Savannah, and above all trusted. His intimates, but no one else, knew that he was in the custom of slipping a ten-dollar-bill into a plain envelope without return address, and sending it to someone he thought was in need. John told an interviewer:

"My father was a religious man. He lived his religion with everybody he knew, rich and poor, Negro and white. He was a gentle, humane man. I admired him. He liked music, and I can remember him in the evenings as he sat in a rocking chair and sang to us. I could listen to him for hours."

John remembered that when he was a very small boy, perhaps three or four, his father would sit in a rocking chair in front of the fireplace and sing old songs, among them Genevieve, Sweet Genevieve; In the Gloaming, and When You And I Were Young, Maggie.

Maybe I was a product of the Roaring Twenties, but a lot of songs I have written over the intervening years were probably due to those peaceful moments in his arms. Secure and warm, I would drift off to dreams, just as, later on, out on the starlit veranda, I would lie on the hammock and, lulled by the night sounds, the cricket sounds, safe in the buzz of grown-up talk and laughter, or the sounds of far-off singing, my eyelids would grow heavy; the sandman was not someone to steal you away but a friend to take you to the land of dreams and another day, there to find another glorious adventure to be lived, experienced, and cherished, and — maybe someday — put into a song.

George Anderson Mercer was a small man who wore high stiff shirt collars. In keeping with formal Southern practice, he wore them even in hot weather, and Savannah in summer can be suffocating. Because of its crushing, humid heat, the family maintained another home at Vernon View, one of about eight such homes overlooking one of the great littoral estuaries which incise the coast from northern Florida up into South Carolina. Vemon View overlooked the Vernon River, and a sea wind was an estival luxury. Green Island and Ossabaw were dimly visible in the distance. A spur railway line ran from the city. A long wooden pier stretched out over the marsh to the water line; at its end was a small sheltering gazebo. Such piers were, and still are, a characteristic feature of this coastal terrain. They are everywhere.

It was a sweet, indolent background for a boy to grow up in. Savannah was smaller then, and sleepy. Trees and azaleas filled the parks, and as we drove out to our place in the country at Vernon View, there was hardly a scene without vistas of marsh grass and long stretches of salt water.

Punctured tires on the Model T made the trips long at times. When the family arrived finally, there were many things to be done: get sawdust to pack the ground bin where we kept the ice, fill the lamps with kerosene, put up the mosquito netting on the beds, and have "Man 'well" walk the cow out from the commercial dairy farm, so that we 'd have our own milk all summer long. The ice cream was homemade, the living generally rural. The twelve miles into Savannah might have been a hundred. Father made the trip in his Ford every day to go to the real estate office.

The help, the colored people who worked for the family, lived over at Back Island, but there was a small cottage just out back of our place where they could sleep over. Between that and the big house we kept the cow and a few chickens, and there was always a dog or two roaming around. The second-floor kitchen was over the garage, which had latticework sides and was connected to the house by a breezeway This eliminated the cooking odors, but necessitated that the food be brought in to the table in covered dishes and on trays. And for that, you had to have servants.

They were plentiful then, and glad to get work as, over on the back of the island, they lived by fishing and what they grew in small gardens. So four or five would come over to work at "reddus"— Red House, so-called from one of the early large homes there, or the roofs. They would do the cooking, cleaning, baby-tending, and all the other things required in a summer household out "on the water". This does not mean we were living in plantation times, but as they received only from two or three to maybe seven dollars a week, plus food, we could afford to live like landed gentry. To get home at night, Manuel and the others would have to go through narrow paths in the "bresh " where rattlesnakes and black moccasins were a constant danger.

The cook was named Bertha Hall; John was especially close to her. The "help" prepared and served the family three meals a day at the formal dining table or on the screened veranda overlooking the river. John always remembered the wind, soft and comforting in the summer or sad and even threatening when hurricanes hovered off the coast. Sometimes heat lightning would illumine great white cumulus clouds with a pink light, and often John would watch the rain beginning miles away across the coastal marshland, then "like silver bayonets, come racing in from the horizon until it thudded on the tin roof like little horses' hooves." The composer Alec Wilder described lyricist Lorenz Hart as an indoor writer and John as an outdoor writer. Images of Georgia inhabit all his work, even the most urbane.

He used to say that his Aunt Hattie swore that he hummed back at her when he was only six months old.

"I think I always liked music," John told an interviewer for ASCAP's magazine, "and probably wanted to be a tune writer rather than a lyricist." His lack of technical command of music bothered him all his life. And that comment reminds me of something he said in one of our many conversations: "I think writing music takes more talent, but writing lyrics takes more courage."

John told the ASCAP interviewer: "I can remember as a little tiny fellow — I think I still had dresses — we used to have cylindrical records, and I loved them.

"And I loved all songs. Always listened to records. And when they got to be the big thick Edison records, I had those, and then when they got to be regular 78s, we had all those. By the time I was ten or eleven years old, I wanted to know who wrote the songs. Somebody told me Berlin was a big writer — I can remember that — and by the time I was twelve I knew about Walter Donaldson and Victor Herbert."

John, in common with many children of the region, spoke Gullah, that all but impenetrable dialect of the tidewater area and the Sea Islands. And from a time before memory he heard the traditional black lullabies and work songs. His Aunt Hattie took him to see the minstrel shows that were still immensely popular, both in the North and the South.

There was no segregation for small children. John and other white children played with black children. They played roly-poly, marbles, and what they called one-o-cat — softball. He always remembered the young black men playing softball after church, wearing hand-me-down uniforms from the Woodberry and Episcopal High Church schools. He remembered and loved the colorful names they bore: May bud, meaning Maybird; Ol’ Yar, Old Year, because he was bom December 31; Buh Dayday, Brother David; and Pompey who, John said, pitched in the manner of Satchel Paige with the style of Meadowlark Lemon.

What was left of the Mammy tradition of plantation days we found in our cook or laundress or nurse. I vividly remember taking a quail I had swiped from a neighbor over to Rachel who, neither knowing nor caring that it was ill-gotten, cooked it deliciously and entertained me in her news-wall-papered shanty with the warmth and friendliness she always had for children.

One summer John broke a leg. It was not set properly and so, later, had to be re-broken and reset. For much of that summer, John was in a plaster cast and hobbling about on crutches. His mother hired his young black friend named Caesar to keep him company at a fee of twenty-five cents a week. One day John's mother, returning to the house at Vernon View, saw Caesar trudging homeward down the road. She stopped to ask what had happened.

Caesar said, "Mistuh Johnny done fire me."

"Why should he do that, Caesar?"

"I ain' know, Mis' Mercer, but we duhplay fish, and I holluh 'e is fish, and 'e fire me!"

Caesar was reinstated in his job, his quarter was restored, and John was admonished to hold his temper in future.

I always was drawn to music and once followed a band around the town when I was six, which my mother must have found difficult to understand. And of course songs always fascinated me more than anything.

It was at that age that he began singing in the boys choir at St. John's Episcopal Church. John sang in church for another eleven years, indeed for the rest of his years in Savannah. He entertained relatives and anyone else he could capture as audience — "Maybe

I was a natural-born ham, even at that age"— with songs such as The Goat that Flagged the Train and Mr. Donnerbeck. He was six in 1915; the Great War had already begun in Europe. The Birth of a Nation had its premiere at the Palace Theater in New York that year, using a full orchestra playing the musical background. Among the big songs that year were Are You from Dixie?, Memories, Paper Doll, There's a Broken Heart for Every Light on Broadway, Pack Up Your Troubles in Your Old Kit Bag, Fascination, I Love a Piano, Keep the Home Fires Burning, and I Didn't Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier.

On the "graffola", as one of the servants called it, John heard the songs of Harry Lauder, all of which he memorized, songs by Crumit and Sanderson, and songs from Broadway shows. No one else in the family seems to have been especially musical, and no one played an instrument. But he devoured music wherever he could find it, tn the church choir or in the singing of a black church within walking distance from the house in Vernon View. He and one of his friends, Dick Hancock, would stand outside and listen, or sometimes venture inside, their white faces conspicuous in the congregation.

Jimmy Hancock, of Bluffton, South Carolina, is Dick Hancock's nephew, and himself became one of John's friends, though not until well after John had become a celebrity. Jimmy said:

"Dick and Johnny were contemporaries and very good friends from early boyhood on up.

"Dick grew up on the water out at a place called Montgomery, which is around the river bend from Vernon View. I'm not sure that Dick wasn't an early impetus in getting Johnny interested in music.

"My father, James Hancock, was Dick's brother. There were seven boys in that family. Daddy was one of the oldest, Dick was the youngest, one of twins."

Another friend who accompanied him to these churches was Jimmy Downey. Downey was also his cousin. Downey moved to New York, married a model turned magazine editor, and became the father Robert Downey, who became a celebrated independent movie director. His son in turn is the gifted actor Robert Downey, Jr. who is Johnny Mercer's third cousin.

The absorption of lyrics from records and minstrel shows and church services unquestionably constituted a serendipitous training for John's life's work. The spirit of the music of that black church infuses Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive. John knew in his deepest being the rhythm of black southern preaching.

A friend of his Aunt Katherine came to Vemon View to interview children to the purpose of compiling a book of stories by children for children. These included the black children John played with, for, as he — and others — attested, no difference was implied or imposed until about the age of fourteen, the time of puberty and sexual arousal. This visitor took down the children's flights of fancy in longhand. Long afterwards, John thought about her. He believed she gave him the confidence to create and perform.

Singing was a favorite form of entertainment all over America, in that time before talkies or radio. Brass bands played in the parks, and the ability to play piano or a brass instrument was common. Especially at Christmas, John remembered, "as the flowing bowl got to flowing," men attending the parties around Savannah would form into quartets to sing old songs. John did a lot of that kind of singing, his ear absorbing elements of harmony.

But as far as musical technique was concerned, I never did make much headway. I tried the trumpet, but couldn't develop a correct embouchure, I've tried on various occasions during my life to learn the piano, never with any great success, and to this day I can I read music properly. I would like very much to have become more fluent in the techniques of music, so that I could have written more tunes of my own.

The joy inspired by the ending of World War I on November 11, 1918, was tempered, and in some families destroyed, by influenza. Ranking with the Black Death as one of the most lethal pandemics in history, it killed an estimated 20,000,000 people in a few months, 548,000 in the United States, one of them John's sister, two years younger than he. Another younger sister, Juliana, survived.

John was surrounded by family, including three half-brothers older than he whom he adored, and his Uncle Walter Uncle Walter had a home at Bluffton, a very small community even now, just across the state line in South Carolina, on the water and facing on the ubiquitous marshes and wooden piers. John would spend parts of his summers there, too. He would fish and swim — he was a good swimmer all his life — and, with the other boys, leap off the jetties and piers into the water. He said later that he was a happy boy in a happy family, loving his brothers and aspiring to be like them.

When the summer heat became insupportable even in Vernon View, the family would repair to Asheville, North Carolina, where George Anderson Mercer had real estate holdings and was building a hotel. The city, in the Appalachian Mountains, is on a plateau that is on average 2,200 feet above sea level. The altitude relieved George Mercer's asthma, from which at times he suffered severely.

John found friends there, too, boys with whom he could look for buckeyes — the seeds of shrubs and trees in the horse chestnut family. They were used like worry stones or Greek worry beads. Carried in the pocket, rubbed by the thumb, they would over time take on a soft gloss and become objects of real beauty. The buckeye was considered a good luck charm, most effective if given to you by a friend. This use of the nut began in the South but in time extended into the west. Many cowboys carry buckeyes, even now. John developed his leg muscles walking the steep streets, or riding his bicycle there.

While his father's hotel was under construction, the Mercers resided in an Asheville home. John remembered a neighborhood girl who on piano played Georgette, Leave Me with a Smile and other now-forgotten hits of the time. Two other, and older, girls, both of whom could play piano and sing, arrived from New York — New York! — and from them John learned some of the latest songs. It was, John remembered, the year of Ted Lewis' big recording of When My Baby Smiles at Me and of Warren G. Harding's defeat of James M. Cox for the presidency. It was, then, 1920.

Thomas Wolfe was born in Asheville on October 3, 1900. He would portray the city, which he called Altamont, and its people vividly, if not always to their pleasure, in his novels. He entered Harvard University that autumn, but he was in Asheville that summer, and no doubt the summers before it. He would turn twenty that October; John would turn eleven that November. The temptation is irresistible to wonder if they ever passed each other in the streets of this quiet resort city, neither knowing who the other was, neither dreaming of the poetic mirror each would hold up to the South and to the United States. Wolfe would write, "a stone, a leaf, an unfound door; of a stone, a leaf, a door. And of all the forgotten faces." John would write: "... through a meadowland toward a closing door, a door marked 'Never more' that wasn't there before."

Wolfe died in 1938. He could not have helped, even if he had tried, knowing some of Johnny's songs.

John encountered Arthur Murray teaching Asheville debutantes the fox trot, which preceded the Charleston, at the Princess Anne hotel, where by now the Mercers were living. Long afterwards, in 1942, John would write Arthur Murray Taught Me Dancing in a Hurry.

He remembered too a young itinerant black pianist playing a piece called Bees Knees over and over. John was particularly impressed that the young man, like he, couldn't read music; it encouraged him. When he was fifteen or sixteen, he heard the Jan Garber orchestra at various locales around Asheville, and was thrilled by it.

John had a taste for girls even then, and in spite of deep shyness.

My nurse used to say I had a girlfriend when she took me out to the park at age three or four. And I remember giving away my pencils and erasers to girls in grammar school, and going to my first dance in my Boy Scout suit.

The second dance was in a girls school gymnasium and I can still see us little bloods, at age eleven or twelve, some of us smoking outside the gym, talking about some of the girls we heard you could kiss and one who had "gone further" than that. At that point I didn 't smoke, and I really didn't want to know if the girl in question was a woman of the world or not. I thought she was too pretty that night, looking all gossamer and spun sugar in her voile or organdy or whatever it was girls wore in the age before blue jeans. Like an angel.

I was determined to get in on the fun, so I manfully went back inside and began dancing. The first time is like swimming: you just have to jump in, and luckily I asked the cutest girl there (and the best dancer), for she was amused and she encouraged me to keep trying. Once started, I wouldn’t stop, and my enjoyment was topped only by my nerve. I can remember the feeling of elation as I lay in bed that night, feeling that I had really accomplished something. I had learned to dance! And I was good; at least, that's what the one girl had said!

Southern girls are terrible flirts with that "Hiya, sugar!" and "Come back soon, y 'hear? " and all that ante bellum jazz, but they're the greatest dancers in the world, bar none. Talk about feeling like a feather in the breeze! You hardly know you've got one in your arms — unless she wants you to know.

Just before he turned thirteen, John was sent to Woodberry Forest school near Orange, Virginia. His father had also gone to Woodberry Forest, and Johnny's three brothers, or more precisely half-brothers, attended Woodberry Forest. George was graduated in the class of 1910, Walter in 1917, and Hugh in 1920. A photo of the Woodberry Forest basketball team of 1916 shows Walter in the back row along with actor-to-be Randolph Scott.

The school was in and on a property that had once been called Woodberry Forest Estate, a farm founded by James Madison's brother. It is provocative to think that John's distant relatives, George S. Patton's father and uncle and grandmother, had once, briefly, lived here while hiding from the forces of the Union during the Civil War. From which window did nine-year-old George Patton pry that body of a dead Union soldier?

At Woodberry, John studied western, ancient, and English history; the New Testament, Old Testament, Caesar; Cicero, mathematics and sciences; Treasure Island, Robinson Crusoe, Gulliver's Travels, Silas Marner; Irving, Macaulay, Emerson, Tennyson, Franklin, Milton, and Shakespeare; and three years of English grammar and two of composition.

It was at Woodberry that John wrote his first lyric. Or so he said. There is a bit of a problem about this. His daughter Amanda has a small lined scribbler containing some pencilled poetry. The internal evidence of the early entries suggests these little pieces were written by his mother; the handwriting is not John's. But later pieces are distinctly in his hand. Amanda has no idea when these entries were written. But one of them, I noticed, explores ideas that turn up much later in the lyric Skylark.

At any event by John's testimony, his first lyric, written one night at Woodberry when he was fifteen, was titled Sister Susie, Strut Your Stuff. The lyric went:

Sister Susie, Strut Your stuff.

Show these babies you're no bluff.

Let these fellows see you step, Do that dance with lots o' pep.

Toss your toe and kick your heel.

This ain't no Virginia reel.

Do your walk — and your strut.

Shake that thing — you know what.

Ain't she hot, boys?

That's my gal! Sister Susie Brown.

When he sang it next day for some of the other boys, several said it was plagiarized. In later years, amused by it, John granted

that it was indeed pilfered, looted from other songs. The style and form were drawn from two big hits of the day, Red Hot Mama and Flamin ' Mama. The name, he thought, probably was derived from If You Knew Susie and Sweet Georgia Brown. The music he had contrived for this little wonder was drawn from all these songs, and yet another of the period, Strut, Miss Lizzie. But for all its obvious derivations, the song reveals even at that early age one of the defining characteristics of John's work: his ear for current vernacular and ability to use it in lyrics.

His schoolmates apparently forgave him this somewhat sorry excursion into songwriting. The Fir Tree, one of the school publications, in his final year notes that he was Football Squad, '26; "Oracle" Board, '26; "Oracle"'27; Daily Dope Editor "Fir Tree"'27; Hop Committee "27; Vice President Madison Literary Society '27; Censor Madison Literary Society '26; Choir '23; '24', '27; German Club '24, '25, '26, '27.

The entry notes that he answered to both John and Johnny and the nickname Doo. The origin of that name remains unknown.

Under a comment "Wit is thy attribute," an item reads:

"John has been with us since the fall of 1922; and during his five-year-sojourn has grown not only in stature, but has become an embodiment and example of true Woodberry Spirit. His willingness and desire to work in the interest of others and his unfailing brightness of personality and humor have made him one of the most outstandingly popular boys in the school.

"John's untiring efforts culminated this year in the attainment of enviable positions among the school activities. His work as an editor both of the Oracle and The Fir Tree has been superb, and his performance has contributed largely to the success of both these publications.

"Among Doo's hobbies and accomplishments there is one which eclipses all others, his love for music. The symphony of Johnny's fancy can best be described with his own adjective 'hot.' No orchestra or new production can be authoritatively termed as 'good' until Johnny's stamp of approval has been placed upon it. His ability to 'get hot' under all conditions and at all times is uncanny. The best explanation we can offer is that we do not properly appreciate melody at its best.

"John is yet uncertain where he will turn for the future, but whether it be to college or to business, the friends he leaves behind are confident of his success and wish him every joy and happiness wherever he may go."

There had been talk in the family of his attending Princeton University, as his father's father had done, and indeed he had already been enrolled. John knew there was a statue at Princeton to his ancestor, the General Hugh Mercer who had fought in the Revolutionary War. But John didn't think he would be able to pass the Princeton entrance exams. And then his father underwent [a financial] reverse that ended the possibility of further formal education. In any case, his academic record at Woodberry Forest precluded Princeton. Considering his brilliance and range of talents, and his fellow students' evaluation of him, his musical interests seem to have crowded all else from his mind, and he was nothing if not honest in his evaluation of his academic performance: he was graduated sixty-first in a class of sixty-five.

George Anderson Mercer, a much-loved man of infrangible integrity — you hear this said of him to this day in Savannah — had founded the G.A. Mercer Company to invest the savings of working people. For some time the company did well, but in 1927, land values in Georgia and Florida, which had been rising rapidly, suddenly dropped. Within weeks George Mercer was out of business and over a million dollars in debt to seven hundred investors. Most of them were sympathetic to him; recriminations were rare. But he could not reconcile the failure with the principles of responsibility by which he had always lived. He declined the option of declaring bankruptcy and the Chatham Savings bank, acting as his liquidating agent, took over his company while George Mercer gave all the money he had, a total of $73,500, to his certificate holders. He was penniless. Yet his reputation remained untarnished, and the bank even lent him money to open a private real-estate office to support his family.

Despite such emotional and financial support, the failure turned a warm, ebullient man into a resigned and silent and self-doubting one.

When Johnny received a letter at Woodberry Forest from his mother, he wrote to her: "The news is a severe blow, but I don't care, except for Father. I only hope and pray that I can be of some service to him."

The family could no longer afford Woodberry Forest. John dropped out of school. His formal education was over.

He told his father, "Don't worry about that money. I'll pay those people back."

George Mercer quietly told him, "Son, you don't realize how much it was. You won't ever have that amount of money."

John's vow sounded like the whistling-past-the-cemetery bravado of a heart-broke boy. It wasn't.”

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)