© - Steven A. Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

"The first thing that comes to mind in thinking about Joe is that he was the greatest drummer in the world. He had students and people that he taught who were in awe of him. His drum solos were musical. ... He was just beyond most drummers."

- Dave Brubeck upon the passing of Joe Morello on 3.12.2011

Warning! This will be a lengthy posting; a very long read.

It's another of the editorial staff at JazzProfiles efforts to take a collection of previous posts about a Jazz musician and "put it all in one place" for future reference.

I've always thought that Joe's gifts as a drummer, both from a technical perspective, as a soloist and as a rhythm section accompanist, were worthy of a book length treatment and perhaps the information and opinions about him in the following piece could serve as the basis for the beginnings of such a project by an energetic and enterprising Jazz fan who shares my views about Joe's greatness.

One aspect of Joe's career that is not covered well in the following materials is the significant role he assumed as a teacher following his retirement as a performing musician with the disbanding of the classic Dave Brubeck quartet in 1968.

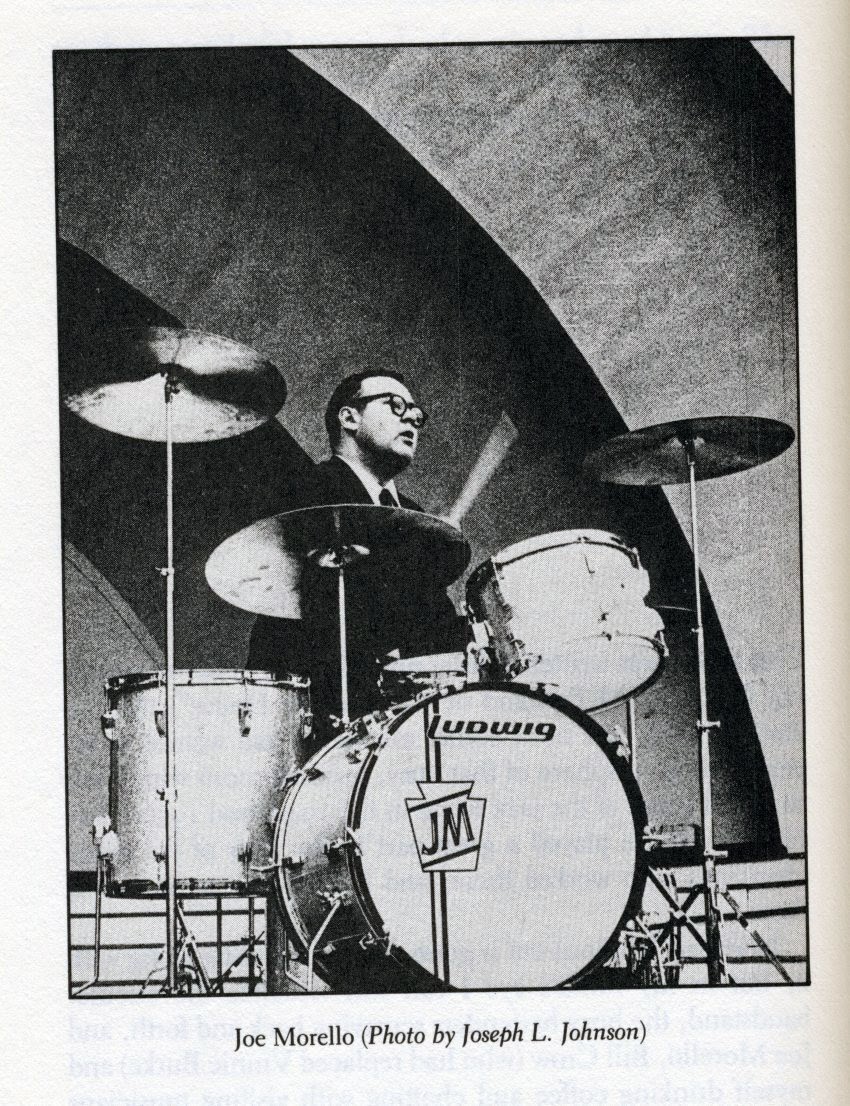

Through the many drum clinics he conducted as a representative of the Ludwig Drum Company, as a private instructor, and through his drumming technique books and instructional videos, Joe helped guide and teach untold number of aspiring drummers until his death in 2011.

“At the start of 1956 Brubeck made a personal decision that proved to be a most important change in his group. After three years with the quartet, drummer Joe Dodge decided to leave. Brubeck took a chance by hiring Joe Morello. Actually, little risk accrued from this decision as Morello was a masterful choice as his polished virtuosity and marked creativity made an immediate contribution to the quartet.

Described by some critics as a sort of purgatory for jazz drummers, Morello was to absolutely flourish in the confines of this supposedly ‘unswinging’ ensemble, especially with its high visibility, daring improvisations and later experimentation with odd or unusual time signatures.

All these factors helped launch Morello to a position of preeminence in the world of jazz drumming and with good cause. The leap into the limelight was no concoction of media hype but well-deserved fame for an exceptional musician.

With the Brubeck quartet, this powerful young workhorse on drums continued to have the same effect on audiences, but now in larger concert halls rather than in small clubs. Soon Morello was no longer a discovery, but a known commodity, emulated by a generation of young percussionists. “

- Ted Gioia,The San Francisco Scene in the 1950’s West Coast Jazz: Modern Jazz in California 1945-1960, [p.96 and p.98, paraphrase].

In 1938, the legendary photographer Alfred Stieglitz was presented with one of the 500 copies of Ansel Adams’ photographic masterpiece – Sierra Nevada: The John Muir Trail.

Upon receiving this gift, Stieglitz declared: “I am an idolater of perfect workmanship and this is perfect workmanship.”

I, too, am an idolater of the perfect workmanship that is to be found in the drumming of Joe Morello as primarily exemplified in the many recordings he made with the Dave Brubeck Quartet from 1956-68. Sadly, Joe made too few recordings outside the DBQ including those under his own name.

Sadly, too, none of the major drum anthologies contain a chapter on Joe nor to my knowledge has Joe been the subject of a biography.

So to compensate for this omission, in the coming weeks, the editorial staff at JazzProfiles thought it might be fun to compile some selected writings about Joe and feature them as postings on the blog.

The following excerpts are from the chapter on pianist Marian McPartland’s trio in bassist Bill Crow’s From Broadway to Birdland: Scene from a Jazz Life [Oxford]. Bill’s reminiscence highlights three of the qualities that I most admired about Joe: [1] his prodigious technique, [2] his well-developed sense of humor which he often exhibited in his playing, and [3] his humility.

“Pianist Marian and I and drummer Joe Morello worked the Hickory House for several years, with occasional hiatuses when she booked a couple of weeks for us in Chicago, Detroit, or Columbus, Ohio. The Hickory House had featured jazz since 1933, but by 1949, like many of the other Fifty-second Street clubs, it had given up on live music. At the time Birdland opened, the Hickory House was using a disc jockey for entertainment.

In 1951, Jerry Shard reintroduced live music there with a trio, and was followed by guitarist Mary Osborne. Marian started there in February 1952, and I joined her two years later. …

When Marian hired Joe Morello [1953], the Hickory House became a mecca for young drummers who admired Joe's superb technique. Joe played at a very tasteful level with the trio, but now and then, when Marian saw that a lot of his fans were in the house, she would give him an extended solo. John Popkin, the boss, often sat at a table near the cash register, perusing the racing news. As Joe pulled out all the stops, we would see the newspaper that hid Popkin's face begin to tremble. Then he would throw it down and rush to the bar, shouting up to the bandstand, "Stop that banging! Stop that banging!"

Morello was a spectacular drummer, but he felt embarrassed when people compared him to Buddy Rich, Max Roach, and Louis Bellson. To fend off such discussions, he invented a mythical drummer named Marvin Bonessa who he said could cut all of them. Marvin was supposedly a recluse who never recorded and rarely came to New York. Marian loved the joke. She and I abetted Joe in it, as did his friend [guitarist] Sal Salvador, to the point that Bonessa began to accumulate votes in jazz polls. Joe still tells some of his young students about the legendary Marvin Bonessa.

Between sets we usually sat in a back booth, where Joe was regularly joined by drummers who came to talk to him and watch his hands. Joe practiced constantly on the table top, using a folded napkin to dampen the sound.

Sometimes he would use just the forefinger of his left hand to keep his drumstick tapping at a rapid, controlled speed. On drum solos he would combine that finger trick with wrist accents.

I fooled around with Joe's drumsticks until I got the hang of his finger trick. When his students marveled at his use of it, Joe would say, "Gee, anybody can do that. Even my bass player can do it."

He'd hand me a stick and I'd casually demonstrate, ruining their day.”

The following video tribute to Marian McPartland finds her along with Bill and Joe performing Tickle Toe.

Marian’s trio with Joe on drums is also featured on the following video tribute to Bill Crow, this time playing How Long Has This Been Going On.

Joe Morello - Drum Talk, - Down Beat, March 26, 1964

© - Steven A. Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

Can’t you just imagine the following interviews occurring in the context of today’s video conferencing capabilities!?

The full introduction explains how the Drum Talk project came to be and a list of all the participants.

In our quest to compile information about Joe Morello in order to develop a more extended profile on him, this introduction is followed by only an ordering of the questions that Joe offered responses to.

Drum Talk Coast-to-Coast, March 26, 1964

The discussion that begins on this page is out of the ordinary in that it was held at three separate locations on separate dates. The first discussion was at Down Beat's New York City office with Art Blakey, Tony Williams, Mel Lewis, and Cozy Cole. The second get-together was appropriately, at the Professional Drum Shop in Hollywood, Calif., with Shelly Manne, Nick Ceroli, Donald Dean, and Mel Lee participating. The last conference was held in Down Beat's Chicago office with Elvin Jones and Joe Morello.

The same basic questions were asked at each discussion; the participants' comments, in some cases, have been juxtaposed in order to show different approaches to the same subject or differences of opinion.

THE PARTICIPANTS:

Cozy Cole has been among the most respected drummers ever since the 1930s when his work with Stuff Smith and Cab Calloway gained wide notice. He currently teaches in New York City.

Art Blakey has led his Jazz Messengers practically around the world in recent years, but he first gained influence as a sideman with Billy Eckstine's big band. He also worked with Buddy De-Franco for some time before forming his own group in the 1950s.

Mel Lewis is a veteran of the Stan Kenton Band and other West Coast musical groups and has toured with Benny Goodman in Russia. He has also done much studio and recording work and is the drummer with the Gerry Mulligan Concert Band. He currently lives and works in New York City.

Tony Williams is still in his teens. A native of Boston, he worked with Jackie McLean before joining the current Miles Davis Quintet.

Joe Morello is one of the most well-liked and respected drummers in jazz. Long a member of the Dave Brubeck Quartet, Morello has won the last two Down Beat Readers Polls.

Elvin Jones has worked with many groups but his greatest fame has come since he has been associated with John Coltrane. One of the most influential drummers, he was winner in the drum division of the 1963 International Jazz Critics Poll.

Shelly Manne is another poll winner, having won the Down Beat Readers Poll several years running. For years one of the busiest Hollywood studio musicians, he has led his own group since the '50s and owns his own night club, Shelly's Manne Hole, in Los Angeles.

Nick Ceroli is a young drummer making a name for himself in the Los Angeles area, where he has worked with the big bands of Gerald Wilson, Les Brown, and Ray Anthony,

Donald Dean is another Los Angeles drummer beginning to make his presence known in the jazz world. He has worked with Kenny Dorham, Dexter Gordon, Curtis Amy, and Carmell Jones, among others. He now is with Gerald Wilson's band.

Mel Lee, though relatively young, has had varied experience with Louis Jordan, Johnny Otis, Phineas Newborn, Etta Jones, Gloria Lynne, and many others. He currently is a member of the Harold Land-Carmell Jones Quintet.

Down Beat:It used to be that other musicians looked down on drummers as being not quite full-fledged musicians. In recent years this has changed some" what. To what extent has it been overcome and how? And how can it be completely overcome?.

Joe Morello: I think that in the last 15 or 20 years the drummer, the role of the drummer, has changed quite a bit, because the music during the last 15 or 20 years has developed to such a degree that the drummer today is not only required to keep time but also to shade and phrase, and so on, with the band in order to create a more interesting rhythm line for the band to play on.

Down Beat:Does the drummer have to be more musicianly now?

Morello: Yeah. Today it's very difficult for a drummer who can't read to go into a recording session — he's in trouble if he's playing with a band that has more than 10 men, if they have charts. He doesn't only have to be able to read them, he has to interpret this music and still create, improvise, make the sound, and make the band swing.

I think drummers are listening more today as well as using the undertones. I think that in the next 15 or 20 years there's going to be another great trend towards development in the rhythm section.

Down Beat:Today there may be an over dependence on the bassist for keeping the time. Has the switch from the bass drum to the high-hat for time-keeping deprived young drummers of essential training? Dizzy Gillespie has been quoted as saying that most drummers — not just the young ones — don't know how to play the bass drum.

Morello: I've played it both ways; I've played in bands where I've used the bass drum on all four, and I've played in bands where I just use it for accents and so on. But I'm inclined to go along with Diz, in that a lot of kids don't put as much importance on the bass drum as they should. Take the old Basic band with Jo Jones. The blend of the piano, bass, guitar, and drums . . . every beat, the bass drum was right there. It never became overbearing.

Morello: A lot of the young drummers have nothing but top—a top sound. You don't hear any bottom to it. The bass drum gives the band a lot of bottom. For instance, our bassist [with the Brubeck quartet], Gene Wright, if I don't play that bass drum in four, he'll look over and sort of nudge me. There've always been arguments between bass players and drummers, like who's going to lay down the time. But Gene wants to hear that bass drum. It should just blend together perfectly. He feels the bass drum is the basic pulse, and he can put the harmonic structure on it. Kids should learn how to play the bass drum!

Morello: I think what Diz was referring to was that a lot of the kids got hooked on this top-cymbal-hi-hit-left-hand when that was the thing, like the hi-hat was the anchor on 2 and 4. The pulse, of course, is always on 2 and 4, but we don’t have to play the high-hat on just 2 and 4; we can play it on 1 and 3 if we want.

Down Beat: Have any of you studied another instrument?

Morello: As far as my background is concerned, I played the violin when I was a child. Then I went into a little piano. I'm not a professional pianist or violinist, but I feel being a little familiar with these other instruments has helped me some. Just recently I've been trying my hand at writing. It's a lot of fun; I think it has helped me as far as playing for the group, being able to pick out things.

Down Beat: How much do you practice and how; do you practice on the pad or the set? If you practice on both, how much do you practice on each?

Morello: I hear this question about practice just about every night in the week. Put it this way: I don't practice as much as I used to or as much as I'd like to. A lot of my work, though, is done on the job. It's not practice—it's playing.

A young drummer should, as we said before, learn as much about the instrument as he can, but one just starting out should devote some time to pad practice; he can hear his mistakes more clearly and develop co-ordination. It requires a tremendous amount of co-ordination to play drums today.

Some teachers today think you should put the pupil on the drum set immediately and start him playing. Well, this is fine, but he'll just have to go back and correct his mistakes later. I'm from the school that says you should diversify your practice.

Certainly the first thing the young drummer should do is find himself a teacher who is familiar with the music business today and what's going on, who has a good knowledge of the instrument, and who can teach him control and technique on the pad. Then he can apply some of these things on the drums, because, after all, this is where he is going to be playing, not on the pad. A lot of teachers feel that pad practice will hurt you — you're not going to take your practice pad out on the job with you. True, but I think there's a happy medium; you can diversify the practice — devote an hour to the pad, an hour to the drums, as much time as you can spend.

Down Beat:What goes through your mind when you're playing either in the section or solo? And are drum solos really meaningless?

Morello: Meaningless? That's up to the individual who's listening. You could be telling the greatest story on earth, and if the person listening doesn't get anything from it, it's meaningless to him. I personally don't think they're meaningless because I enjoy playing them. I try to develop a musical form or theme and extend it.

As far as what goes through my mind, I couldn't say. I never thought about it.

Down Beat:There's been an increase in recent years of jazzmen playing in different time signatures 9 in 5/4, 7/4. Can a young drummer do himself a disservice by concentrating on these exotic times, to the neglect of 4/4?

Morello: Odd time signatures have been done for years in classical music; it's just that recently they've been applied to the jazz idiom. I don't see why 5/4 can't swing; I think it does. We've been fairly successful with them in our group. It won't hurt the young drummer to investigate these signatures. It'll give him larger scope. Naturally, he should learn to play 4/4, 3/4—and as far as that goes, 2/4. He should be able to play anything. Jazz shouldn't be limited to just 4/4. Everything develops.

A lot of drummers today, including myself, are trying to play cross-rhythms. I'm searching and trying to do different things rather than the things that have been done. And I know they can swine. We do it.

Down Beat:How ignorant are we of complex rhythms and how can a study of African and Indian rhythms help or hinder the young drummer?

Morello: I think he should also know what went on before him, how rhythm patterns developed. When he's ready to go into this, it's a necessity for him to do it; but half-knowledge is not good.

African and Indian rhythms, which are quite complex, can be incorporated into playing, if handled wisely. But I don't think a youngster just starting off should go into this; he should learn how to count four, the basic things first.

The following video from the BBC program “Jazz at Club 625” shows Joe in action in 1964 with the Dave Brubeck Quartet on Sounds of the Loop.

Joe Morello - An Interview with Les Tomkins

In Joe Morello there is a dreamer who is nonetheless a down-to-earth realist; someone who is reserved yet outspoken; shy much of the time, yet frequently uninhibited.

These are not just characteristics that set Joe apart as a man. They also help to set him apart as a jazz musician—one who leaves critics and fellow workers alike raving about his fantastic technical ability, his taste, his touch, and his ideas.

In other words, to put it crudely, he possesses that uncanny sense of 'putting the right sound in the right place at the right time.'"

© - Steven A. Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“Any good Jazz musician has developed from hard work and hard thought, a personal conception. When he improvises successfully on the stand or in the recording studio, it is only after much thought, practice and theory have gone into that conception, and it is that conception which makes him different from other Jazz musicians. Once he knows what he is doing, in other words, he can let himself go and find areas of music through improvisation that he didn’t know existed. Jazz improvisation, therefore, is based on a paradox – that a musician comes to a bandstand so well prepared that he can fly free through instinct and soul and sheer musical bravery into the musical unknown. It is a marriage of both sides of the brain ….”

- Eric Nisenson, Ascension: John Coltrane and His Quest [p. 53]

“I let myself go. I find as I go along, I feel like I’ve learned from many people, and yet I’m told that I’ve influenced other musicians. I hardly believe I’m as talented as some others. Someone with talent possesses a kind of facility and plays well as early as 16 or 17 much better than I could play at that age. I had to practice a lot and spend a lot of time searching and digging before I got anywhere. And because of that, I later became more aware of what I was doing, I wasn’t an imitation. I found myself with a synthesis of the playing of many musicians. From this something came out and I think it’s really mine.”

- Pianist Bill Evans, as told to Jean-Louis Ginibre

“The finger technique, practice method and of the drummer other drummer’s rave about- the Dave Brubeck quartet’s inimitable Joe Morello.”

- Les Tomkins, Jazz writer and critic

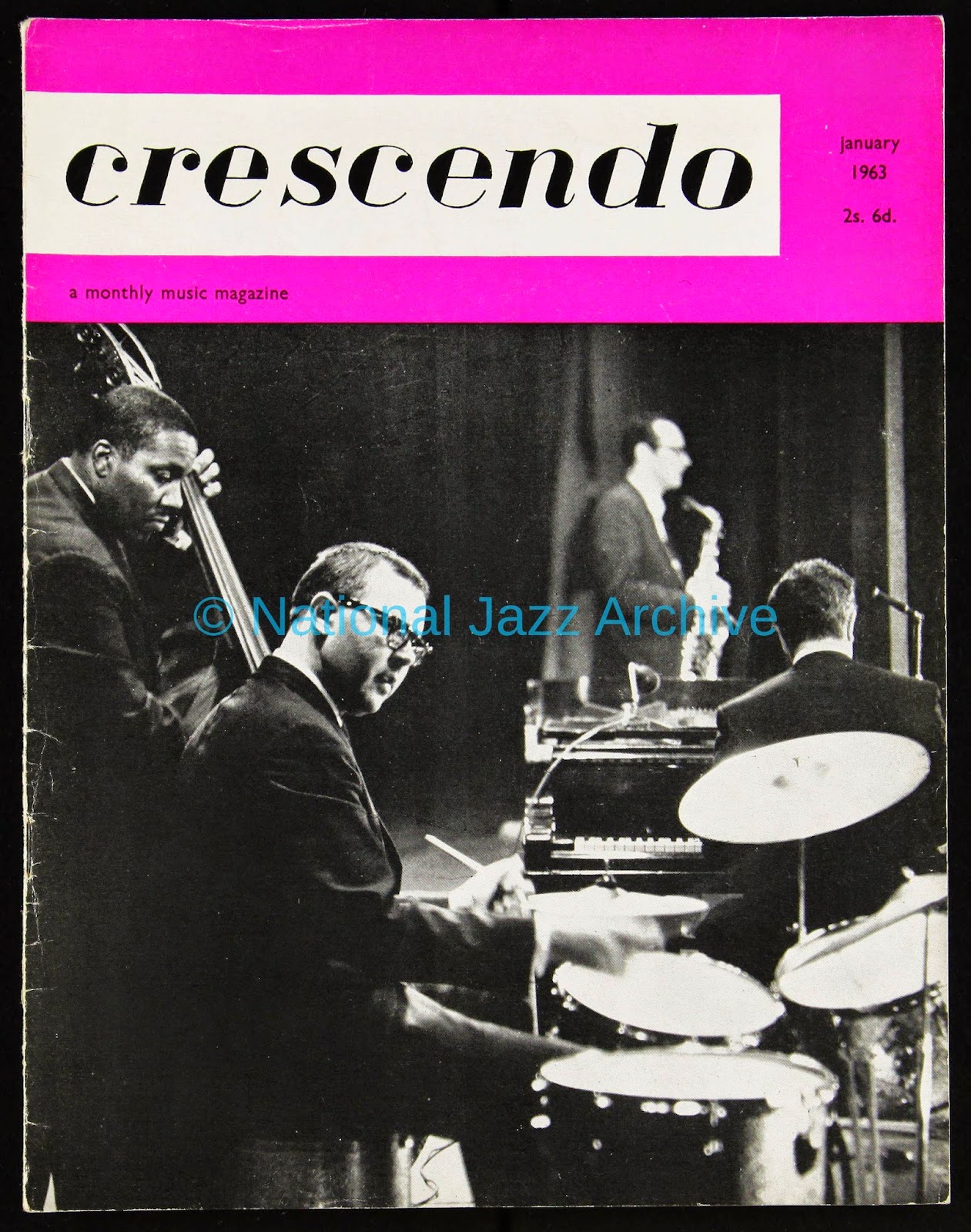

The following interview appeared in the January 1963 edition of Crescendo Magazine.

“The amazing Joe Morello beat out impressive patterns on his practice board to illustrate and embellish his statement to me on drumming in general and his unique contribution in particular.

“Yes, I’ve used the same [drum] set-up for I guess the last ten years - except that I added another cymbal about a year ago. They [Ludwig drum kit] hold up well under successive one-nighters and that silver colour is sort of a good luck thing.’

‘Sticks? I usually don’t change them around and added my own a while back. I couldn’t find one that had the action that I like so I fooled around and made some, had them turned for me and they became my model. And it’s not too bad, although they have been coming through kind of thin lately.’

Joe added ruefully - ‘The new Buddy Rich model is similar to mine - only a little heavier.

When I asked him how he tuned his drums he said that [trombonist, composer, and arranger Bill Russo had posed the same query to him a few nights earlier. ‘He liked the snare drum sound and wondered if I had any trouble turning them over here [At the time of this interview, Joe may still have been using cow hide heads on his drums and they would have been affected by England’s wet climate].’ I told him: “Not too much.”

‘There was one night on the tour when we arrived late and I didn’t have the chance to check the drums. The small tom-tom sounded like a tympani.

‘But usually when they arrive at the hall they get accustomed to the temperature inside. And so when I get there about fifteen minutes before the show, I tighten them up and tune them to my liking.

‘There’s not really a set way of doing it. The only thing I suggest on tuning is that I keep the snare drum head fairly tight and the batter head [bottom snare drum head] a little looser. A lot of people go around turning their drums a fifth and a fourth - b-flat on the bass drum and so on. I’ve never bothered doing that. I just tune them so that they sound good to me.

Inevitably, I brought up Joe’s seemingly-magical finger technique to find out how long it has been a part of his playing and how he set about perfecting it.

‘This finger control thing is something that started a long time ago in the French Conservatory. That was the first school to utilise this way of manipulating the sticks.

‘I never studied in France or anything but years ago in my hometown of Springfield, Massachusetts, I used to sit for hours trying to figure out how they could sustain this single beat with the left hand.

‘Before that it used to be all stiff wrist, much like a lot of the boys here in England are doing it. They are holding it stiff, which is not the way to do it.

‘I was just trying to figure, letting the stick rebound real loose - by itself. Of course the teacher I was with at the time said “No, you must never let the stick rebound.” ‘This was supposed to be wrong. There was a taboo on the thing.

‘Then Louie Bellson came through with the Tommy Dorsey band. He was playing this way. He got it from Murray Spivak in Hollywood, who used to teach it quite well. [Murray taught privately for many years in his clinic and was the drum master other drummers went to when they had problems with their playing]. Louie had a good understanding of it. So I talked to him and he gave me the basic principle of it, which opened a lot of doors for me.

‘I took it upon myself to analyze it and to develop it to suit my own personality in playing. That is to say I adopted it anatomically to fit what I can do with my hands. I do it a little differently from Louie - and I think everyone else does because it is sort of an individual thing.

‘Ever since that time, Louie and I have been getting together periodically to discuss this.

THE GREATEST

I’d like to mention another teacher here, who is dead now, but who in my opinion was the greatest drummer in the world - thought I can’t stand the term when applied to Jazz drumming. He was Billy Gladstone. He was a fantastic drummer. He had all these things going. He was the best exponent of it. [Billy Gladstone was a famed Broadway show drummer who often shared the percussion platform with Max Manne, the father of Jazz drummer Shelly Manne, with whom he became close friends].

‘He was a great influence as far as my hand development, technique and sound are concerned. He taught me a lot and helped me tremendously. Swinging drum solos weren’t “his cup of tea” - but for touch, technique and speed, he was the closest to a genius I’ve ever seen.

‘For the past four or five years, I’ve been in the process of writing a book about finger control. I’ll probably never finished it. Murray Spivak told me he’s been trying to write a book since 1951. It’s easier to demonstrate than put on paper.

‘The principle is relatively simple, although the application is a little more difficult. The stick is propelled with the finger instead of the wrist and arm. All you are doing is rebounding the stick with the first finger. But it has to be done with control. There must be no tension in the arm and hand, so as to get a loose handhold between the thumb and third finger.

‘The best way to practice it is to get a full turn of the left wrist, letting the stick bounce freely. As you close your first finger down, you’ll feel the pull. It’s a matter of sustaining that. It takes considerable practice over long periods.

‘I’ve been reasonably successful with it although for the last six months, I haven’t had time to devote to a practice schedule to keep it in shape.

‘The technical part of drumming is strictly physical. It requires a certain amount of training and exercise each day to maintain a decent technique.

The Tympani Grip

‘The tympani grip? [Matched-sticks grip]. There’s nothing wrong with doing it this way if you like it. This is a natural way of holding the stick For me - I feel very comfortable playing the orthodox way, especially when I’m behind the drum set. I have the high-hat cymbal on one side and everything and I feel cramped if I don’t do it this way. I’m used to this way, but I’m not opposed to the other way.

On rules and their flexibility - ‘There are several different stages in one’s development. The beginner should stick to the rules. You can’t break the rules unless you know them.

‘Once you know the rules, you can alter them to suit your personality. But when you are first going to a teacher and he says “Do it this way,” you should say: “But it’s easier this way.” It might be easier at that moment but in the long run you might be heading for an endless pit. There are certain basic rules anatomically for playing drums that should be adhered to. Eventually there will be individual characteristics that will sneak into your playing.

On teachers as opposed to books: ‘Printed matter is great - it has pictures and text, as far as that goes. But a teacher can demonstrate a thing for you. That’s the difference. All you have with a book is a visual notation of an idea - but you can’t hear it. Whereas a teacher is telling you and showing you at the same time, so you can hear how it should sound.

‘You may see something written down and do it as written, but you may not be executing it the way the author had in mind. The teacher can tell you this. Hands and wrists very a lot, so everybody has different problems. In the initial stages, a teacher can help you to solve them.

‘ It’s important to get a good teacher. There are very few people who have done anything worthwhile on drums who haven’t studied first including, Louie Bellson (who is a very schooled musician), Buddy Rich and Max Roach. A lot of Jazz drummers will try to create an image and say: “I never studied or practised.” But if you use your head this is a lot of nonsense. It’s like my saying: “I don’t eat for five weeks at a time.” You’d laugh at me.

Joe went on to speak on a more personal level. He explained his purpose in practicing: ‘I never practice hot licks. I practice for development. My practice board is like an exercise bar, like a boxer with a punching bag - strictly for developmental purposes.

‘Now when I’m playing - from practicing so much and studying - my hands will respond to whatever I want to do - within reason.

‘I don’t think I’ll ever reach my goal. I hear some things and I may never reach them. I would like to develop flawless technique which would allow me to play what I want to play anything that comes into my mind.’

He outlined his attitude about working in a rhythm section: ‘When I am playing Jazz drums, I try to complement all that is going on around me. If it is an exciting group, you let your feeling take over. If I feel that it requires accents with the left hand and with the bass drum - fine. If I feel that the mode of the music calls for straight rhythm, I’ll play just that. There are no set rules. Again, it’s individualism.

‘I don’t believe that a drummer show throw in a flurry of accents and bass drum kicks if they are meaningless. I don’t think this makes any sense.

Joe referred to the difficulty of writing Jazz feeling into an arrangement: ‘A drum part for a big band - or any group in the Jazz idiom - is written more as a cue sheet. You have all your cuts where the band stops. You might also have a two-bar pick up. And usually they will mark in just the brass figures in the band.

Interpretation

‘Now this is where interpretation comes in - and a teacher can take you over a lot of these hurdles if he knows anything about Jazz interpretation.

You take four eighth notes. They will be written one after another and the brass will phrase them in more of a 12/8 feeling. But if the arranger has to sit down and break each measure down into 12/8 time and put the triplets in, the measure would be eight inches long.

‘So this is something that a drummer has to get used to - learning how to see one thing and phrase it differently.

‘Reading is very important today. Drums have developed to such a degree that it’s no good anymore for a fellow to just pick up the sticks and beat out a hot drum solo. Today, the drummer adds tonal color to the band. He’s playing more with the band. He’s more of an integral part of it and he’s depended on more than he was years ago.

‘Years ago a drummer was just seen and in a lot of cases wasn’t heard and didn’t mean anything. When they hired the band they’d day: “I want seven musicians and a drummer.” Now the drummer has to be a musician, too.’”

Here’s more of Joe’s brilliant drumming in a 1961 video featuring the classic Dave Brubeck Quartet in a performance of Castilian Blues.

Joe Morello - In A Big Band Setting

© - Steven A. Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“The music on this album represents Joe Morello at his peak, and shows off some sides of his playing that have been relatively undocumented. Here was a drummer who was equally at home with small combos and big bands; a drummer who could handle the most complex time signatures and who was equally adept at straight-ahead swing; a drummer who had as much technique as any drummer who has ever lived, but who always put the music first.”

- Rick Mattingly, insert notes to [Joe Morello RCA Bluebird- 9784- 2 RB]

By any standard of measurement and without the need for any hyperbole, Joe Morello was a phenomenal musician who happened to express his genius on drums. And despite the incomprehensible derision he endured from some members of the East Coast Jazz Establishment - “He didn’t swing.” [?!] - he was an exceptionally brilliant drummer who swung his backside off.

Anyone who has ever had anything to due with the instrument in a Jazz environment, simply understand this - Joe was incomparable.

While we are fortunate to have many recorded examples of his playing in small groups, especially those he made during a three years association with pianist Marian McPartland’s Trio [1953-1956] and those made as a member of the “classic” Dave Brubeck Quartet [1956-1968], sadly, there are too few recordings of his extraordinary drumming in a big band setting.

The following insert notes by Rick Mattingly to Joe Morello [RCA Bluebird- 9784- 2 RB] provides some explanations for this void.

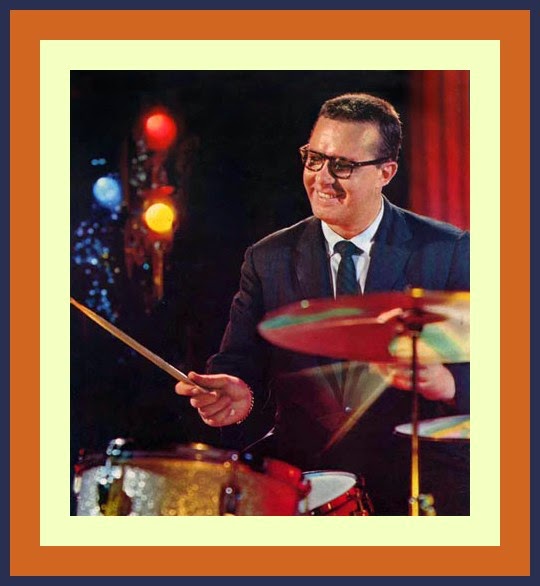

“It was the early '60s, and the hottest jazz group going was the Dave Brubeck Quartet, who had achieved the rare distinction of having a number-one hit on the pop charts. The tune was called "Take Five," and its two main points of interest were the 5/4 time signature and the drum solo, played by Joe Morello. The record epitomized the "cool jazz" of the period, and Morello was the ideal drummer for that era. His style was firmly rooted in the swing and bebop traditions, but Joe was also a schooled performer who had studied with George Lawrence Stone of Boston and Billy Gladstone, snare drummer at Radio City Music Hall. Morello's polished technique, combined with the odd-meter time signatures favored by the Brubeck group, gave his playing an intellectual quality that fit right in on the college campuses where the Brubeck Quartet enjoyed much of their success. With his glasses and generally studious expression, Joe even looked somewhat like a college professor.

Among drummers, Morello was highly respected. When he first arrived in New York in the mid-'50s, his first order of business was to check out all of the local drummers. Stories are still told about how he would approach a drummer and ask about some little technical trick he had seen that drummer pull off. The other drummer, often with a patronizing air, would demonstrate his lick for Joe, who would then say, "I think I see what you're doing. Is this it?'— thereupon playing the drummer's lick back at him faster and cleaner.

When Morello began a three-year stint with Marian McPartland at New York's famed Hickory House in 1952, it gave all the other drummers in town the chance to check out Joe. Many still recall sitting with him at a back table between sets, where he would demonstrate his techniques by playing on a cocktail napkin. But while Morello quickly proved that he had all the chops of a Buddy Rich, he became noted for his restraint, only pulling off his pyrotechnics when it was musically appropriate to do so.

Morello joined Dave Brubeck in 1955, for what was to become a 12-year association. About the same time, he had offers from both Benny Goodman and

Tommy Dorsey, but he turned them down to go with Brubeck. "At the time," Joe says, "it looked to me as if big bands were on the way out. So it seemed to make more sense to go with Dave." It was a wise decision, as history has borne out. The Brubeck Quartet was the perfect setting for Morello to develop and display his unique approach, and during those years he repeatedly won the "best drummer" award in down beat,Metronome, and Playboy jazz polls.

During his tenure with Brubeck, Morello also became involved with the Dick Schory Percussion Pops Orchestra, with whom he recorded a couple of albums on RCA. After one of those sessions, Schory remarked to Morello, "It's about time you made your own record." The RCA executives agreed, and sessions were set up in June 1961.

"We took the title of the album, It's About Time [LPM-2486] from Schory's comment," Morello recalls. "Then we decided that we would only do songs that had the word 'time' in the title." Interestingly enough, despite the title of the album and the reputation Joe had for his expertise with unusual time signatures, there was very little of that type of playing on the record. "I wanted to do straight-ahead things on my album," Joe explains, "because I was doing so much of that other stuff with the Quartet. I wanted this album to be a whole different concept."

Because Morello was on the road so much with Brubeck, composer/arranger Manny Albam was enlisted to prepare the music and book the musicians. One player that Morello specifically requested, though, was saxophonist Phil Woods. "Phil and I grew up together in Springfield, Massachusetts," Joe says. "We played together as kids. He would be listening to Charlie Parker, I would be listening to Max Roach, and we would get together and try to imitate them. Phil and I always dreamed of having a group together, and although that never happened, we did make a few records together over the years. He's such a great player."

Another notable player on that album was Gary Burton, who was still a teenager at the time. "I met Gary through Hank Garland," Joe recalls. "I had worked with Hank at the Grand Ole Opry when I was 17. Then, after I was with Brubeck, I did a record with Hank, and he had this kid playing vibes. It was Gary, and that was his first album [Hank Garland, Jazz Winds from a New Direction, [Columbia LP 533]. When Gary came to New York, he stayed with me for a while, and then he stayed with Manny Albam after that. We did my album about a year after we had done Hank's record, and Gary had really improved a lot." Morello had also gotten Burton involved in Schory's Percussion Pops Orchestra, where they recorded together, and when Burton did his first solo a I bum for RCA [LPM 2420], New Vibe Man In Town, Morello was the drummer.

It's About Time did well enough that RCA invited Morello back to do a second album a year later. A few of the tunes on the first album had featured a brass section along with Phil Woods on sax, so this time it was decided to do a full-out big band record. Again, Manny Albam was enlisted to write the charts and hire the musicians, and again Phil Woods and Gary Burton were involved. But the album was never released. "RCA wanted me and Gary to have a group together," Joe remembers. "We had played on each other's albums, and RCA said that if we started a group together, they would really get behind it and publicize us. But I was too comfortable with Dave, so I wouldn't do it. And RCA couldn't see putting all this promotion behind my solo albums if I was still going to be doing all of that recording with Dave on Columbia. So they just didn't release the second album."

Those tapes remained in the RCA vaults for 27 years. But Morello had a copy, and he would occasionally play it for people. One person he played it for was Danny Gottlieb, a student of Joe's who has had a distinguished career of his own, working with such notables as Gary Burton, the Pat Metheny Group, John Mclaughlin, and the Gil Evans Orchestra, and who now has his own group, Elements. Gottlieb subsequently brought a copy of the tape to producer John Snyder,along with It’s About Time, and the results are contained herein [Joe Morello RCA Bluebird- 9784- 2 RB]

This collection kicks off with "Shortnin" Bread," from the unreleased big band album. "This was a little drum feature that we used to do with the Quartet," Joe recalls. "It always went over well, so I wanted to do it on my album." Morello's melodic approach to the drums is well represented here, as is his ability to kick a big band. "I think I could have been a good big band drummer if I'd had the chance to play with one for any length of time," Joe says. Judging by this, he certainly could have.

Next up is "When Johnny Comes Marching Home," featuring Morello's brush playing. Playing precise military-style figures with brushes is no mean accomplishment, and it is a good example of how Morello utilized his considerable technique in a subtle way. On the surface, Morello's drum breaks and rhythmic figures are rather basic ("l just played simple little things tha tfit with the band," he says), but when one considers the technical difficulties involved in achieving crisp articulation with brushes, one begins to appreciate Morello's degree of control.

Morello's control of fast tempos is evident on "Brother Jack," also from the unreleased big band sessions. "That's a pretty good tempo for a big band," Joe says. "Manny didn't want it to be that fast, but I wanted to take it up." Joe shows off his blazing single-stroke roll technique during the drum breaks in the middle, and ends the tune with a more thematic solo. Phil Woods is also featured on this tune.

"Every Time We Say Goodbye" is from It's About Time, and utilizes a brass section to enhance the core quintet. Morello concentrates on supporting the soloists, Woods, Burton, and Bob Brookmeyer.

Also from the first album, "Just in Time" is a quintet tune with spirited solos by Woods, Burton, and bassist Gene Cherico. "I had pretty good hands back then," Joe says of his four-bar breaks, which display his sense of phrasing, as well as his sense of humor.

"It's Easy" comes from the big band sessions, and Joe remembers it as the last thing that was recorded. "I didn't have a drum chart for this, and we only had time to do a couple of takes," Morello recalls. "When the first drum break came up, I didn't know what was going on," he laughs. Nevertheless, by the second break, Morello sounds as if he had been playing the tune for years. Colorful hi-hat work adds to the mood of this piece.

"Shimwa," is a piece that Morello wrote for the Brubeck Quartet. "We didn't play it that much, though," Joe says, "so I had Manny arrange it for the big band album. It's basically a showcase for the drums. I wanted an African-type motif, and I tried to get the effect of a couple of drummers playing." The effect is achieved by Morello's use of polyrhythms, and by his ability to set up an ostinato pattern with his left hand, leaving his right hand and bass drum free to play contrasting rhythms.

Another "time" tune, "Summertime" was arranged by Phil Woods, and features solos by Woods, Burton, and pianist John Bunch, who was no stranger to working with good drummers; he had recently been with Buddy Rich's band. Morello concentrates on straight-ahead, supportive playing here. "I didn't want to do too many drum solo things," Joe explains. "On a lot of albums by drummers, every tune has a drum solo, and let's face it, too many drum solos are boring. I wanted to be more musical."

"A Little Bit of Blues" is another big band chart by Manny Albam, and features distinctive solos by Hank Jones and Clark Terry. No technical fireworks from Morello here, just great feel.

"It's About Time" was the title tune from th first album, and is basically a setup for Morello's drum solo. All of the Morello trademarks are here: the speed, the polyrhythms, the left-hand ostinatos, the phrasing. Another feature of the tune is its changing time signature; it goes into 6/4 for Phil Woods' solo.

The quintet from the first album is featured on "Every Time "which displays the smoother side of Morello's brush playing. Joe has high praise for Burton's contribution to this piece. "Gary had really learned to phrase well," Joe comments. "When I first heard him, he was playing everything right on the beat, but by the time we recorded this, he was really adept at back-phrasing." Bunch and Cherico also have solo spots here, and Morello adds a melodic drum break.

Phil Woods wrote "MotherTime"for the first album,an uptempo 12-bartune

that features solos from Bunch, Cherico, Burton, and Woods, followed by fours between Morello and Woods. Joe's breaks include his use of space and his famous left-hand ostinato.

"Time After Time" is a ballad that features Phil Woods, backed by Morello's sensitive brush playing. Unlike a lot of drummers, Morello always disengaged his snares when playing brushes, which produced a drier, more defined sound, "Phil has such a nice feel in this tune," Morello comments, "especially during the double-time section."

Considering the tempo of "My Time Is Your Time," not to mention the large ensemble, most drummers probably would have used sticks. But Morello pulls out his brushes, driving the band with intensity rather than volume. Burton and Woods solo, and Morello takes several breaks in which he shows again that he can be as articulate with brushes as most drummers are with sticks.

This collection concludes with a Dave Brubeck composition, "Sounds of the Loop," from the unreleased big band album. During the ensemble section of the tune, Morello displays a more "open" style of big band drumming, only catching the major figures and concentrating more on keeping the time moving forward. The chart is primarily a vehicle for Morello's drum solo, and it is a definitive example of melodic, thematic drumming.

The music on this album represents Joe Morello at his peak, and shows off some sides of his playing that have been relatively undocumented. Here was a drummer who was equally at home with small combos and big bands; a drummer who could handle the most complex time signatures and who was equally adept at straight-ahead swing; a drummer who had as much technique as any drummer who has ever lived, but who always put the music first.

—RICK MATTINGLY

Joe Morello - "It's About Time"

© - Steven A. Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“One thing about Dave Tough: he always was Dave Tough, just as Buddy Rich always was what he was. Tough realized we are what we are. The important thing is to be put into a musical situation where what you are can ‘happen.’ Tough found his place with Woody Herman.” [And Joe Morello found a place where he could ‘happen’ in the classic Dave Brubeck Quartet from 1956-1968].

- Mel Lewis, drummer and bandleader

“Joe Morello: One of my favorite drummers was Davey Tough. 'Cause he could keep a nice rhythm with a band and he kept good time. He didn't hardly do anything with his left hand. He was just straight ahead on the big cymbal, but he got it cookin' real good.

Sidney Catlett I used to listen to.

Scott K Fish: Did you ever get to meet those guys?

JM: Sid Catlett I met once. One time in New York.

J.C. Heard was another fine drummer. I don't know if you've ever heard of him.

And then Jo Jones, who is still a good friend of mine. He's still here. Old man Jo Jones. ‘Jonathan Jones to you.’ [Morello mimics Jo Jones’ raspy voice.] Boy, that guy taught me a lot, because I played opposite him for about six or seven weeks at the Embers. He was working with Tyree Glenn and Hank Jones. He use to play his bass drum open, see. He had a little 2O-inch bass drum, and a snare drum, cymbal, and a hi-hat cymbal. That's all he had. Oh, and he had one little floor torn. And he'd get up on the drums with brushes and he'd get that bass drum going. [JM taps drum stick on leather sofa cushion, imitating the sound Jo Jones' would get from this bass drum at the Embers].

SKF: When you say "open," you mean he had no felt strips at all?

JM: Not at all. [Keeps tapping stick on couch] and he'd get a sound just like that. A good sound.

I'd get up there and I'd play something and it would go BOOM BOOM BOOM BOOM. And I'd say to him, "Jo, how do you do...?" And he wouldn't talk to me for the first two or three days. He just sort of flugged me off, you see.

But I sat down and I watched that f***in' bass drum, and I said, "I'm doing something wrong."'Cause he sounds tap, tap, tap, and when I hit it it goes BOOM, BOOM, BOOM. I couldn’t play it!

The only way you could play it, I found out, was by pressing the beater ball on the bass drum pedal into the head. He’d play up on his foot like that, but he’s been playing it like that for so long that he can control it, see. Jo was always playing toes down with his heals up!

I learned a lot about hi-hats from Jo, because Jo would always get a breathing sound from his hi-hats. We became good friends.”

- Scott K. Fish, Modern Drummer, 1979

In a previous posting entitled “Joe Morello In A Big Band Setting,” we highlighted Rick Mattingly’s insert notes to Joe Morello RCA Bluebird- 9784- 2 RB, a CD that essentially combined 7 previously unreleased big band sessions from 1961-62 with eight of the ten tracks that were issued featuring Joe Morello in a quintet setting on the RCA LP It’s About Time [RCA LPM-2486].

Since the original liner notes to It’s About Time were not included with the the CD reissue, the editorial staff thought it might be helpful and instructive to have these available online.

Joe’s quintet included his boyhood chum, Phil Woods, who also arranged some of the tunes along with Manny Albam [the arranger for all of the subsequently released big band charts], Gary Burton on vibes [these were some of Gary’s earliest recordings], John Bunch on piano and Gene Cherico on bass.

You will find two of the tracks from It’s About Time on the video tributes that conclude this portion of our ongoing feature on one of the most respected and revered Jazz drummers of all time.

ABOUT THIS ALBUM BY GEORGE AVAKIAN [Producer]

“Every limit in jazz and popular music has been stretched and broken with the passing years. Technical skills have been sharpened; musicians have turned what was once dazzling virtuosity into the professional norm. The frontiers of harmony are extended constantly—yesterday's radical dissonances are today's conventions.

"Times" have changed, too. The simple time-rhythms of the past are no longer enough for today's musicians. Improvised subdividing of the standard four-beat measure by the earlier jazzmen was a hint of what was to come. Many musicians today use 6/4, 3/4, 5/4, and far more complicated rhythms with the same freedom and skill with which variations on the customary 4/4 are tossed off. Drummers—notably, at first, Art Blakey and Max Roach—were the natural leaders of this development.

But it was a pianist Dave Brubeck who took over leadership in the extension of rhythmic horizons. As Dave's drummer, Joe Morello played a key role in winning a large public to what have remained a private enjoyment for under for musicians only. In this, his first album under his own direction, Joe clearly displays a number of the rhythmic devices for which he, as a member of the Brubeck Quartet, has become known. But - make no mistake - Joe’s first love is swinging and driving a band, whether small or large. So this album is indeed, “about time” - but the preoccupation with time never gets in the way of making swinging music.

Joe’s fantastic technique - probably the most overwhelming, ever - is never just for showing off. Throughout the record, he is heard as an integral member of the group; even his longest solo is actually an extension of what the band has been playing. That he is the member who provides most of the spark and drive for each performance is plainly evident at all times.

A basic small combo is heard throughout the album, with a brass ensemble added for four numbers (I Didn't Know What Time It Was, Every Time We Say Goodbye, Time on My Hands, and It's About Time). Manny Albam, arranger and conductor for these numbers, has integrated the combo so that there is frequently a concerto grosso quality to the sound of the ensemble.

Phil Woods, alto saxophonist throughout this set, is the arranger of five of the six remaining selections. Completing the album is a trio improvisation (Fatha Time) by pianist John Bunch, bassist Gene Cherico, and Joe.

Joe's approach, in assembling the musicians and asking Manny and Phil to write for them, was that the music must, at all times, swing. There was no attempt to use complex rhythms for their own sakes. The musicians, of course, had to be chosen with care. The principal soloists — Woods, Bunch, and vibraphonist Gary Burton — are strong "blowers." They are soloists of the type who dig in and go.

Woods, the best-known soloist, is one of the finest saxophonists of the post-bop era. He is a musician whose blazing musical temperament is perceptible even on ballads. Gary Burton is a teenage virtuoso who has bowled over seasoned musicians for the last two years and is just beginning to become known. He impressed Chet Atkins, RCA Victor's recording manager in Nashville (and one of the great guitarists of all time), so deeply that Chet promptly signed him. His first RCA Victor album will appear shortly. John Bunch, whose vigorous piano is sprinkled liberally throughout this album, is a youthful veteran of the Benny Goodman, Woody Herman and Maynard Ferguson bands, and has also played in the small combos of two of the country's most popular drummers, Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich.

As for more on Joe Morello — well, few people would be better qualified to tell you about him than Marian McPartland, with whose trio Joe sprang to fame—first with his fellow musicians, and then the jazz public.”

ABOUT JOE MORELLO BY MARIAN McPARTLAND

“Joe Morello is a drummer's drummer. As long as I have known him, which is close to ten years (when he first came to New York and sat in with me at the Hickory House in 1952), he has always been surrounded by drummers who came from all over to listen to him play, to talk to him, to work out or to study his amazing technique at close range. Joe joined my trio in 1953, and it was always interesting to me to see how much time he devoted to the study of the drums, even to practicing every spare minute between sets. He was absolutely fanatical about this, and at times there seemed to be a kind of controlled fury in his playing — sort of a fierceness which belies the appearance of this quiet, soft-spoken guy. Only when he plays does he reveal some of the inner conflicts and frustrations that have shaped and directed him in his restless drive for perfection.

Joe was a child prodigy on the violin, and can play piano quite well. He is a sentimental person who thinks deeply, who loves to daydream and to philosophize while listening to music—every kind of music. His musical tastes run all the way from Casals to Sinatra to Red River Valley. He is a complex person: on one hand, gentle, quiet and imaginative; then, in the next instant, a complete extrovert, doing impressions of his friends and laughing like a schoolboy; then again he becomes remote, moody, shut off from everybody in his own self-contained little world.

In the past few years Joe has traveled all over the world with the Dave Brubeck Quartet. He is now a seasoned performer, and shows the results and benefits of working with Dave. He has made a great reputation, and this is revealed in a different approach to his solos.

His musical ideas run along new lines; he uses his fantastic technique to better effect than ever, and he seems to have broadened his scope, not only in his playing but in various little intangible ways — in his increased confidence, in a certain gregariousness he never used to have. Yet, he is humble and at times almost disbelieving of his success. He has unquestionably made a great contribution to the Brubeck group, and I am sure that Dave would be among the first to agree that the success of tunes like Take Five, the Paul Desmond composition which put the Quartet on the nation's best-selling charts, is in some measure due to Joe's unique conception of unusual time signatures and his ability to play them interestingly.

The time is right for Joe, now one of the most illustrious sidemen in jazz, to record for the first time as a leader (although, of course, in public he is still the drummer of the Brubeck Quartet). For Joe, this has a very special meaning. It is not just an opportunity to perform with a hand-picked group of musicians, including his great friend Phil Woods as saxophonist and arranger. This album represents the fulfillment of a long-expressed desire which grew out of his first tentative experiments, as a boy, with a pair of brushes on the kitchen table in his home in Springfield, Massachusetts.

I believe that Joe was born to be a brilliant musician. This album will justify and renew the faith he has in himself, as well as the high praise and respect he has received from musicians all over the world. In discussing Joe recently, Buddy Rich called him "the best of the newer drummers; he has tremendous technique, and he is the only one to get a musical sound out of the drums."

The tunes and arrangements by Manny Albam and Phil Woods give him ample scope to express himself — whether with sticks on a hard-swinging, white-hot, uptempo tune such as Just in Time; or the delicate mimosa-leaf shading with brushes in Time After Time or Every Time We Say Goodbye.

In Joe Morello's playing you can hear the fire, the relentless drive, the gentleness, and the humor that is in him, and he has surrounded himself with some of the best musicians there are, to help him make this — his first album on his own — great.

Joe Morello - The Early Years

© - Steven A. Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“Everyone associated with the clinics is happy. "For every one that he does, I could book ten," said Dick Schory of the Ludwig Drum Company, Morello's sponsor. "There has never been a drummer who can draw people like he does, and he can keep them on the edge of their seats for two hours. He's a very good extemporaneous speaker, and he's such a ham that I'm sure he'd rather do this than play the drums. He razzles and dazzles them with his playing, and he has this fantastic sense of humor — it's not dry-as-dust lecturing — he makes it interesting, and he believes in it."

He will relax the crowd at the start of the clinic by kiddingly referring to it as a "hospital for sick drummers — and I'm the sickest of them all." Or "I guess all you people must need help or you wouldn't be here." Last year in London, at the first clinic there, he greeted deafening applause with, "If I'm elected, I promise ... ." After a particularly sizzling display, which had everybody on his feet applauding, he shook his head morosely and muttered, "I must be getting old."

But since I've been with Dave [Brubeck’s Quartet], I've had a lot of acclaim, and I'm very grateful for it. Some manifestations of that acclaim have been like dreams come true—you've never dreamed the dreams I've dreamed and had them come true! If I never do more than I have done already, I'm proud and happy for what I've accomplished — God has been good to me.”

- Joe Morello, drummer extraordinaire

The following feature on Joe Morello by Jack Tracy from the September 7, 1955 edition of Down Beat magazine may be the first about him to appear in a major Jazz periodical. I am still researching, but I have yet to find one that is dated earlier.

It is followed by two essays about Joe by pianist Marian McPartland in whose trio Joe performed from 1953-1956.

“JOE MORELLO is a big, shy, bespectacled drummer with the fastest hands this side of Buddy Rich and a too-modest appraisal of his own abilities, which are considerable enough to have won him this year's New Star award in the Down Beat jazz critics' poll.

He has been a member of the Marian McPartland trio for about two years now, in addition to spurring a number of record dates with such men as Tal Farlow, Gil Melle, Lou Stein, and John Mehegan.

His deft touch with brushes, his fantastically capable left hand, and the originality of his solos have earned him plaudits galore from musicians and close observers, and it appears that from now on he will be garnering considerable fan interest as well.

BUT IF JOE'S father had had his way, Morello would now be a violinist. He played that instrument for several years but then quit and wanted to begin on drums when he was 17.

His father practically threatened disinheritance, but Joe went ahead, and Springfield, Mass., now can lay claim to a man who could become one of jazz' most celebrated tubmen.

JOE WORKED AROUND Springfield for awhile with local groups and inevitably was drawn to New York, where he worked some off -nights at Birdland, spent some time with guitarist Johnny Smith, subbed for Stan Levey in the Stan Kenton orchestra for a couple of weeks, then joined Marian.

"It was the greatest thing that could have happened to me," says Marian. "Joe is the perfect sideman. He can play anything in any tempo, isn't a bit temperamental, and is just gassing everybody who heard him these days.

"When I went on the Garry Moore show regularly last year, it was Garry who insisted that Joe come along, too, even though it was originally planned that I do a single."

PERHAPS THE MAN who is most impressed by the talents of Morello, and one who raves about him every chance he gets, is his McPartland sidekick, bassist Bill Crow.

"He's great to work beside," says Bill. "Practices all the time. He keeps working on the idea of making extended solos a continuous line, just as if they were compositions. And more often than not, they're now coming off.

"I think there's only one guy around who still really scares Joe," he adds. "That's Buddy Rich. If Buddy is anywhere around, Joe will go in and sit for hours just to watch his hands and feet."

MORELLO READILY admits to his admiration for Rich, saying simply, "Buddy Rich is my drummer.

"Sonny Igoe is a great one, too. But I don't mean that I want to play like them. I just admire them for what they can do. I want to do something different. I think anyone who is serious about his instrument wants to be an individualist."

For a guy who has been playing drums only 11 years, and professionally for little more than three, he already has made remarkable strides in that direction.

And if the number of times his name keeps popping up in musicians' conversation about drummers is any indication, he will not be long in reaching his goal.

—tracy”

The Fabulous Joe Morello

Marian McPartland

All in Good Time

“The French they are a funny race. And drummer Joe Morello, who is of French extraction, does nothing to confound the maxim. His Gallic characteristics, combined with his quiet New England upbringing, seem to be at the root of his personality—high-spirited, full of fun, yet serious and sensitive to a marked degree.

In Joe Morello there is a dreamer who is nonetheless a down-to-earth realist; someone who is reserved yet outspoken; shy much of the time, yet frequently uninhibited.

These are not just characteristics that set Joe apart as a man. They also help to set him apart as a jazz musician—one who leaves critics and fellow workers alike raving about his fantastic technical ability, his taste, his touch, and his ideas.

Joe was born, brought up, and went to school in Springfield, Massachusetts. His father, now retired, was a well-to-do painting contractor who had come to the United States from the south of France. Joe's mother, who died when he was seventeen, was French-Canadian.

A gentle, music-loving woman who taught him as a small boy the rudiments of piano playing, she encouraged and fostered his obvious love for music. She saw that many of the pleasures others find in life would be impossible for Joe: his extremely poor vision prevented him from participating in most of the games and sports other children enjoyed. Music, she seemed to feel, was the best compensation—and perhaps much more than mere compensation.

When Joe was seven, his parents bought him a violin, and he began to show a precocious talent for and interest in music. Moody and withdrawn, he disliked school and made few friends. One friendship he did form, however, was with a neighbor, Lucien Montmany, a man who, crippled and confined to his home much of the time, took a great interest in the boy. He would play piano for him by the hour, and encouraged him to pursue music.

"Bless his soul, he was such a wonderful guy," Morello said. "And he helped me so much. He gave me confidence in myself, and after I had started studying drums, he used to say to me, 'Joe, you've got to practice all you can now, because you won't have the time later on.’

"And you know, he was right."

But Joe did not become interested in the drums until he was about fifteen. Until that time, he remained preoccupied with piano and violin—which explains in part the musicality of his work and his extreme sensitivity to other instruments.

He had made a few cautious forays into the rhythmic field. But these efforts were largely confined to performing with a couple of spoons on the edge of the kitchen table, as accompaniment to phonograph records. It irritated his parents and his sister Claire considerably.

But at last, with money earned from an after-school job in a Springfield paint shop, he bought himself a snare drum, sticks, and brushes and later—with money gained from the diligent selling of Christmas cards, among other things—the rest of the set. He found a teacher, Joe Sefcick, and began sitting in around town.

It was about this time that Morello formed a close friendship with another man who was to emerge as an important name in jazz: guitarist Sal Salvador.

"It was sometime in 1946 that I met Joe," Salvador recalled recently. "I was playing one of my first jobs when he came into the club with his father. He must have been about seventeen. I remember his father tried to get him to sit in, but he hung back.

"But finally he did agree to sit in, and he had very good chops even then. It was Joe Raiche's band. He was pretty well the king around Springfield, but we had heard talk about Joe Morello. And so he and Joe Raiche played some fours, and everybody thought he was great. I really dug what he did with the fours, especially since he was only playing on the tom-tom, and I asked him about working a job with me. After that we kept calling each other for jobs which we never seemed to get.

"From then on we were inseparable, we saw each other all day, every day."

Salvador tells several amusing stories that illustrate how much Joe (and several of his friends) wanted to play.

"Teddy Cohen, Chuck Andrus, Hal Sera, Phil Woods, and Joe and I would all get together and play as often as we could," he said. "Saturday afternoons we used to go to Phil's house. One day it was so hot that we moved the piano out onto the porch. Joe moved his drums out there, too. The weight was too much. The porch tipped! Everyone panicked.

"But Joe was the first to recover. And he was the first one back indoors, with his drums set up to play.

"We were so anxious to play that we'd set up and start things going just anywhere we could. Once we drove out to a club called the Lighthouse. But it was closed when we got there, so we set up and started playing, right in front of the place.

"Pretty soon the cops came and chased us away. I guess we kids just didn't think about what the grownups had to go through with us in those days ..."

Morello and Salvador continued working together at an odd assortment of jobs, including a radio broadcast, dances, and square dances. "Anything we could get," Salvador said. Then Morello started going to Boston to study with a noted teacher named George Lawrence Stone.

"I think it was Mr. Stone who finally made him realize that sooner or later he would have a great future in jazz," Salvador said. "And, of course, he gave Joe this great rudimental background. In fact, Joe became New England rudimental champion one time.

"In 1951, he joined Whitey Bernard. Finally, after working on the road with him, he went to New York in 1952 and put in his union card. I had gone there and had been begging him to come for some time. But he would say, 'No, I'm not ready yet. There are too many good drummers there.’

"However, he finally made it, and as you know, the Hickory House was one of the first places that he and I came to, to hear your group."

From here on, Joe Morello's story becomes quite personal to me.

At the time, there was a constant swarm of musicians at the bar of the Hickory House, where I was working. Sal had often told me about this "fabulous" drummer from Springfield. But being so accustomed to hearing the word "fabulous" used to describe talent ranging from mediocre to just plain bad, I was slightly skeptical.

But one night Joe came in with Sal. Mousie Alexander, who was playing drums with me at the time, introduced us. Joe Morello, a quiet, soft-spoken young man about twenty-three, looked less like a drummer than a student of nuclear physics. Yet I was, after hearing so much about him, eager to hear him play.

We got up on the stand, Joe sat down at the drums and deftly adjusted the stool and the cymbals to his liking. And we started to play.

I really don't remember what the tune was, and it isn't too important. Because in a matter of seconds, everyone in the room realized that the guy with the diffident air was a phenomenal drummer. Everyone listened.

His precise blending of touch, taste, and an almost unbelievable technique were a joy to listen to. His technique was certainly as great (though differently applied) as that of Buddy Rich. And through it all, he played with a loose, easy feeling interspersed with subtle flashes of humor reminiscent of the late Sid Catlett.

That is the way Joe sounded then, and I will never forget it. Everyone knew that here was a discovery.

Word of his amazing ability spread like fire among the musicians, and soon he was inundated with offers of work. It was not long afterwards, following a short period with Stan Kenton's band and some dates with Johnny Smith's group, that Joe became a regular member of my group.

We opened at the Blue Note in Chicago in May 1953 and later returned to the Hickory House.

Every night it was the same thing: the place was crowded with drummers who had come to hear Joe.

He practiced unceasingly between sets, usually on a table top, with a folded napkin to deaden the sound and prevent the customers and the intermission pianist from getting annoyed. Sometimes the owner would walk over and say irascibly, "Stop that banging!"

But usually no one bothered him, and he gave his time generously to the drummers who came to talk with him. Soon he had some of them as pupils.

And wherever we played, it was the same. Young drummers appeared as if by magic, to listen to Joe and talk to him and to study. They arrived at all hours, in night clubs, at television studios, in hotels. We called them "the entourage." Several of them now are playing with top groups in various parts of the country.

During this period, Joe, bassist Bill Crow, and I started doing a lot of television, and recorded several LPs for Capitol. Nineteen-fifty-five was a good year for us. We received the Metronome small group award, and Joe won the Down Beat International Critics poll new star award. It was presented to him on the Steve Allen Show.

About that time, Joe and Bill were making so many freelance record dates that I told them I thought I should open an office and collect 10 per cent!

Some of Joe's best work was done on those sessions. At least, the best I have heard him play. There is a wonderful recording that he and Bill made with Victor Feldman and Hank Jones which, unfortunately, never has been released.

But there are other albums in which you can hear Joe at this period. One was an album done by Grand Award, with a group led by trombonist Bob Alexander. Chloe is easily the finest track. There's an interesting vocal and drum exchange with Jackie Cain and Roy Krai in a piece called Hook, Line and Snare in an album they did together. And he recorded some sides with my husband Jimmy and myself. This was more on the Dixieland kick, which points up Joe's extreme flexibility.

There are also some wonderful sides Joe made with Gil Melle, Sal Salvador, Sam Most, Lou Stein, John Mehegan, Tal Farlow, Helen Merrill (with Gil Evans' arrangements), and with Jimmy Raney and Phil Woods.

Alas, though for a time he turned down all offers, I was not to keep Joe with my group forever. And when I lost him as my drummer, my one consolation was that he was going to join a musician whom I respected very deeply: Dave Brubeck.

Joe joined the quartet in October 1956. Since then he has gone on growing.

Indeed, his playing has altered considerably, partly because of his fanatical desire for improvement and change, partly because the kind of playing Dave requires from a drummer is different from the techniques that Joe used with my group.

With me, Joe had concentrated more on speed, lightness of touch, and beautiful soft brush work. Dave, both a forceful personality and player, requires a background more in keeping with his far-reaching rhythmic expositions, and someone who can match him and even surpass him on out-of-time experimentation.

Today, Joe, though a complete individualist, hews closely to Dave's wishes as far as accompaniment is concerned. But he cannot help popping out with little drummistic comments, subtle or explosive, witty or snide — depending on his mood at the moment.

It is Dave's particular pleasure to go as far out as possible in his solos, and have the rhythm section carry him along. For this reason, the drummer must have a very highly developed sense of time and concentration to keep the tune moving nicely while these explorations are under way.

Bassist Gene Wright and Joe — "the section," as they refer to each other — do this most ably. Wright's admiration for Joe is unbounded.

"There's never been any tension at all from the day I joined the group," he said. "Joe makes my job very easy. We play together as one, and when a drummer and bass player think together, they can swing together. As a person, he's beautiful, and it comes out in his playing.

"There are no heights he cannot reach if he can always be himself and just play naturally. His potential is far beyond what people think he can do, and he'll achieve it some day."

Like any musician, Joe has detractors, those who can be heard muttering to the effect that he's a great technical drummer but doesn't really lay down a good beat — or, in more popular parlance, "He don't swing, man." But these detractors are remarkably few, and Brubeck is vehement in saying, "They're out of their minds!"

"Joe swings as much as anybody," Dave said, "and he has this tremendous rhythmic understanding. You should have heard him over in India with the drummers there. They just couldn't believe an American drummer could have that kind of mind, to grasp what they were doing. They said it would probably only take him a little while to absorb things it had taken them a lifetime to learn.

"As it is, Joe assimilates things quicker than any jazz musician I know, and he has the biggest ears. He was able to do many of the things the Indian drummers were doing, but they couldn't do what he does because they're just not technically equipped for it.

"How has his playing affected my group?

"I would say we have a better jazz group since Joe joined us. He really pushes you into a jazz feeling. And in his solos, when he gets inspired, he does fantastic things. Sometimes he gets so far out it's like someone walking on a high wire. Of course, he doesn't always make it, and then he'll say, "Oops!" But then he'll come right back and do it next time around. He is a genius on the drums."

Paul Desmond is just as forthright in his comments about Joe. "Joe can do anything anybody else can do, and he has his own individuality, too," Brubeck's altoist said. "Do we usually play well together? Yes, unless we're mad at each other! Naturally there are times, as in any group, when there might be a little difficulty of rapport if we are feeling bad. Playing incessantly, the way we do, night after night, it's almost impossible once in a while not to be bored with each other and with one's self. This is never true of Joe, especially on the fours."

I asked Paul how he felt about the rave notices that Joe has been getting since he joined the group.

"Well, Dave and I have been on the scene for about ten years now," he replied, "and it's only natural that somebody new, especially a drummer as good as Joe, would rate the attention of the critics. He definitely deserves all the praise he is getting. I think he's the world's best drummer, but it's his irrepressible good humor on and off the stand that I dig most of all."

Similar views were shared by a good many other persons, among them Joe's friend and long-time co-worker at the Hickory House, bassist Bill Crow, though he expresses it a little differently.

He always has amazingly precise control of his instrument at any volume, at any tempo, on any surface, live or dead. He's very sensitive to rhythmic and tonal subtleties and has a strong time sense around which he builds a very positive feeling for swing. Extraordinarily aware of the effect of touch on tone quality, he uses his ears and responds with imagination to the music he hears associates play.

With these assets, I nevertheless feel Joe isn't a finished jazz drummer, considering his potential. He can play any other kind of drum to perfection, but I don't think he's saying a quarter of what his talent and craftsmanship would inevitably produce if he were playing regularly with musicians who base their rhythmic conception on the blues tradition.

I know that Joe is attracted to this tradition, uses it as a focal point in his establishment of pulse, and feels happiest when he is playing with musicians who work out of this orientation. But he has never yet found a working situation where anyone else in the band knew more than he did about the subtleties of it . . .

He still has to find an environment that would demand response and growth on a deeper level. He needs to solve the problems presented by soloists like Ben Webster, Sonny Rollins, Harry Edison, or Al Cohn. He has to discover from his own experience how the innovations of Dave Tough, Sid Catlett, Kenny Clarke, or Max Roach can be applied to various musical situations. But primarily, he needs to play with Zoot Sims-type swingers who will reaffirm his feeling for loose, lively time.

Now that Joe's home base is San Francisco, he and his wife Ellie (they were married in 1954 while we were playing at the Hickory House) maintain an apartment in town. They have formed a close friendship with Ken and Joan Williams, owners of a San Francisco drum supply shop where Joe teaches every day he's not on the road and where he practices incessantly. The feeling his pupils have for him is nothing short of hero worship, and his opinions and views are digested word for word.

As Sam Ulano, a noted New York drum teacher puts it, "One of the great things Joe has done to influence the young drummers is to make them more practice conscious. He has encouraged them to see the challenge in practice and study, and I think it is important, too, that people should know how Joe has completely overcome the handicap of poor vision to the extent that few people are even aware of it. This disability has acted as a greater spur to him, already filled as he is with deep determination to perfect his art, and others with similar problems can take note and gain hope and encouragement from it."