© - Steven A. Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“Everyone associated with the clinics is happy. "For every one that he does, I could book ten," said Dick Schory of the Ludwig Drum Company, Morello's sponsor. "There has never been a drummer who can draw people like he does, and he can keep them on the edge of their seats for two hours. He's a very good extemporaneous speaker, and he's such a ham that I'm sure he'd rather do this than play the drums. He razzles and dazzles them with his playing, and he has this fantastic sense of humor — it's not dry-as-dust lecturing — he makes it interesting, and he believes in it."

He will relax the crowd at the start of the clinic by kiddingly referring to it as a "hospital for sick drummers — and I'm the sickest of them all." Or "I guess all you people must need help or you wouldn't be here." Last year in London, at the first clinic there, he greeted deafening applause with, "If I'm elected, I promise ... ." After a particularly sizzling display, which had everybody on his feet applauding, he shook his head morosely and muttered, "I must be getting old."

But since I've been with Dave [Brubeck’s Quartet], I've had a lot of acclaim, and I'm very grateful for it. Some manifestations of that acclaim have been like dreams come true—you've never dreamed the dreams I've dreamed and had them come true! If I never do more than I have done already, I'm proud and happy for what I've accomplished — God has been good to me.”

- Joe Morello, drummer extraordinaire

The following feature on Joe Morello by Jack Tracy from the September 7, 1955 edition of Down Beat magazine may be the first about him to appear in a major Jazz periodical. I am still researching, but I have yet to find one that is dated earlier.

It is followed by two essays about Joe by pianist Marian McPartland in whose trio Joe performed from 1953-1956.

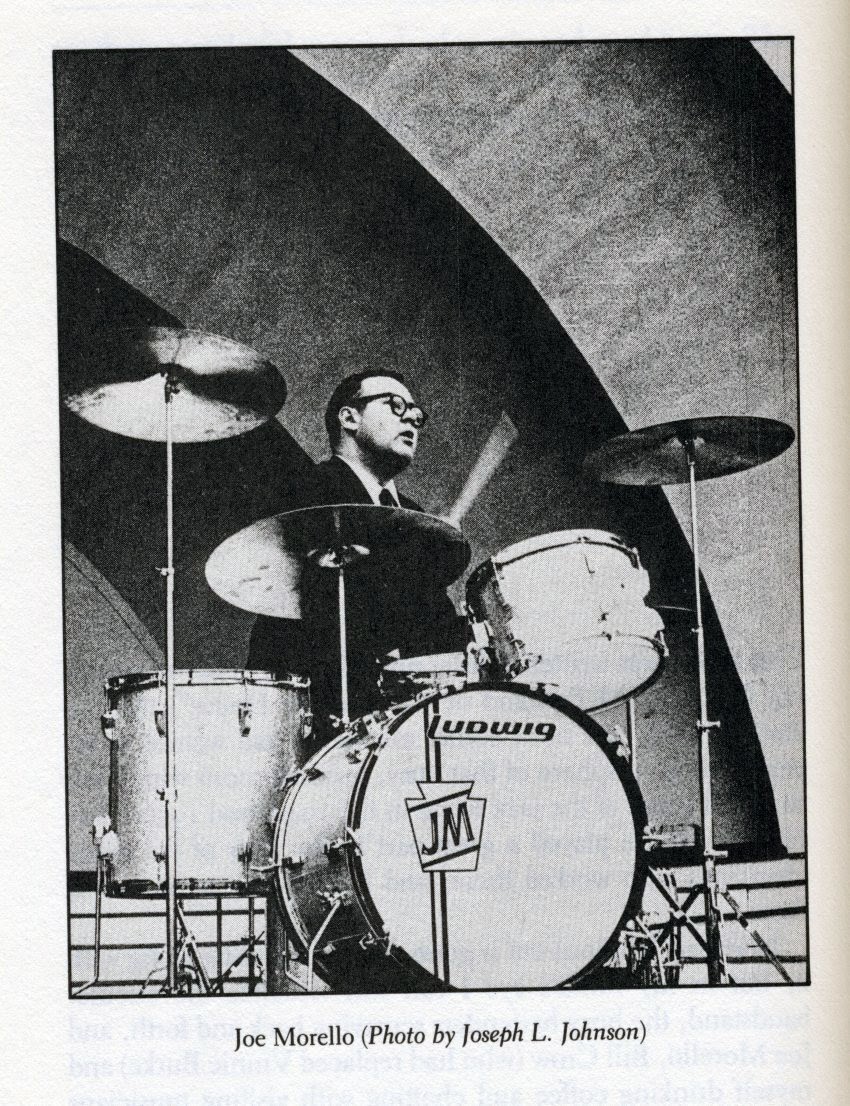

“JOE MORELLO is a big, shy, bespectacled drummer with the fastest hands this side of Buddy Rich and a too-modest appraisal of his own abilities, which are considerable enough to have won him this year's New Star award in the Down Beat jazz critics' poll.

He has been a member of the Marian McPartland trio for about two years now, in addition to spurring a number of record dates with such men as Tal Farlow, Gil Melle, Lou Stein, and John Mehegan.

His deft touch with brushes, his fantastically capable left hand, and the originality of his solos have earned him plaudits galore from musicians and close observers, and it appears that from now on he will be garnering considerable fan interest as well.

BUT IF JOE'S father had had his way, Morello would now be a violinist. He played that instrument for several years but then quit and wanted to begin on drums when he was 17.

His father practically threatened disinheritance, but Joe went ahead, and Springfield, Mass., now can lay claim to a man who could become one of jazz' most celebrated tubmen.

JOE WORKED AROUND Springfield for awhile with local groups and inevitably was drawn to New York, where he worked some off -nights at Birdland, spent some time with guitarist Johnny Smith, subbed for Stan Levey in the Stan Kenton orchestra for a couple of weeks, then joined Marian.

"It was the greatest thing that could have happened to me," says Marian. "Joe is the perfect sideman. He can play anything in any tempo, isn't a bit temperamental, and is just gassing everybody who heard him these days.

"When I went on the Garry Moore show regularly last year, it was Garry who insisted that Joe come along, too, even though it was originally planned that I do a single."

PERHAPS THE MAN who is most impressed by the talents of Morello, and one who raves about him every chance he gets, is his McPartland sidekick, bassist Bill Crow.

"He's great to work beside," says Bill. "Practices all the time. He keeps working on the idea of making extended solos a continuous line, just as if they were compositions. And more often than not, they're now coming off.

"I think there's only one guy around who still really scares Joe," he adds. "That's Buddy Rich. If Buddy is anywhere around, Joe will go in and sit for hours just to watch his hands and feet."

MORELLO READILY admits to his admiration for Rich, saying simply, "Buddy Rich is my drummer.

"Sonny Igoe is a great one, too. But I don't mean that I want to play like them. I just admire them for what they can do. I want to do something different. I think anyone who is serious about his instrument wants to be an individualist."

For a guy who has been playing drums only 11 years, and professionally for little more than three, he already has made remarkable strides in that direction.

And if the number of times his name keeps popping up in musicians' conversation about drummers is any indication, he will not be long in reaching his goal.

—tracy”

The Fabulous Joe Morello

Marian McPartland

All in Good Time

“The French they are a funny race. And drummer Joe Morello, who is of French extraction, does nothing to confound the maxim. His Gallic characteristics, combined with his quiet New England upbringing, seem to be at the root of his personality—high-spirited, full of fun, yet serious and sensitive to a marked degree.

These are not just characteristics that set Joe apart as a man. They also help to set him apart as a jazz musician—one who leaves critics and fellow workers alike raving about his fantastic technical ability, his taste, his touch, and his ideas.

Joe was born, brought up, and went to school in Springfield, Massachusetts. His father, now retired, was a well-to-do painting contractor who had come to the United States from the south of France. Joe's mother, who died when he was seventeen, was French-Canadian.

A gentle, music-loving woman who taught him as a small boy the rudiments of piano playing, she encouraged and fostered his obvious love for music. She saw that many of the pleasures others find in life would be impossible for Joe: his extremely poor vision prevented him from participating in most of the games and sports other children enjoyed. Music, she seemed to feel, was the best compensation—and perhaps much more than mere compensation.

When Joe was seven, his parents bought him a violin, and he began to show a precocious talent for and interest in music. Moody and withdrawn, he disliked school and made few friends. One friendship he did form, however, was with a neighbor, Lucien Montmany, a man who, crippled and confined to his home much of the time, took a great interest in the boy. He would play piano for him by the hour, and encouraged him to pursue music.

"Bless his soul, he was such a wonderful guy," Morello said. "And he helped me so much. He gave me confidence in myself, and after I had started studying drums, he used to say to me, 'Joe, you've got to practice all you can now, because you won't have the time later on.’

"And you know, he was right."

But Joe did not become interested in the drums until he was about fifteen. Until that time, he remained preoccupied with piano and violin—which explains in part the musicality of his work and his extreme sensitivity to other instruments.

He had made a few cautious forays into the rhythmic field. But these efforts were largely confined to performing with a couple of spoons on the edge of the kitchen table, as accompaniment to phonograph records. It irritated his parents and his sister Claire considerably.

But at last, with money earned from an after-school job in a Springfield paint shop, he bought himself a snare drum, sticks, and brushes and later—with money gained from the diligent selling of Christmas cards, among other things—the rest of the set. He found a teacher, Joe Sefcick, and began sitting in around town.

It was about this time that Morello formed a close friendship with another man who was to emerge as an important name in jazz: guitarist Sal Salvador.

"It was sometime in 1946 that I met Joe," Salvador recalled recently. "I was playing one of my first jobs when he came into the club with his father. He must have been about seventeen. I remember his father tried to get him to sit in, but he hung back.

"But finally he did agree to sit in, and he had very good chops even then. It was Joe Raiche's band. He was pretty well the king around Springfield, but we had heard talk about Joe Morello. And so he and Joe Raiche played some fours, and everybody thought he was great. I really dug what he did with the fours, especially since he was only playing on the tom-tom, and I asked him about working a job with me. After that we kept calling each other for jobs which we never seemed to get.

"From then on we were inseparable, we saw each other all day, every day."

Salvador tells several amusing stories that illustrate how much Joe (and several of his friends) wanted to play.

"Teddy Cohen, Chuck Andrus, Hal Sera, Phil Woods, and Joe and I would all get together and play as often as we could," he said. "Saturday afternoons we used to go to Phil's house. One day it was so hot that we moved the piano out onto the porch. Joe moved his drums out there, too. The weight was too much. The porch tipped! Everyone panicked.

"But Joe was the first to recover. And he was the first one back indoors, with his drums set up to play.

"We were so anxious to play that we'd set up and start things going just anywhere we could. Once we drove out to a club called the Lighthouse. But it was closed when we got there, so we set up and started playing, right in front of the place.

"Pretty soon the cops came and chased us away. I guess we kids just didn't think about what the grownups had to go through with us in those days ..."

Morello and Salvador continued working together at an odd assortment of jobs, including a radio broadcast, dances, and square dances. "Anything we could get," Salvador said. Then Morello started going to Boston to study with a noted teacher named George Lawrence Stone.

"I think it was Mr. Stone who finally made him realize that sooner or later he would have a great future in jazz," Salvador said. "And, of course, he gave Joe this great rudimental background. In fact, Joe became New England rudimental champion one time.

"In 1951, he joined Whitey Bernard. Finally, after working on the road with him, he went to New York in 1952 and put in his union card. I had gone there and had been begging him to come for some time. But he would say, 'No, I'm not ready yet. There are too many good drummers there.’

"However, he finally made it, and as you know, the Hickory House was one of the first places that he and I came to, to hear your group."

From here on, Joe Morello's story becomes quite personal to me.

At the time, there was a constant swarm of musicians at the bar of the Hickory House, where I was working. Sal had often told me about this "fabulous" drummer from Springfield. But being so accustomed to hearing the word "fabulous" used to describe talent ranging from mediocre to just plain bad, I was slightly skeptical.

But one night Joe came in with Sal. Mousie Alexander, who was playing drums with me at the time, introduced us. Joe Morello, a quiet, soft-spoken young man about twenty-three, looked less like a drummer than a student of nuclear physics. Yet I was, after hearing so much about him, eager to hear him play.

We got up on the stand, Joe sat down at the drums and deftly adjusted the stool and the cymbals to his liking. And we started to play.

I really don't remember what the tune was, and it isn't too important. Because in a matter of seconds, everyone in the room realized that the guy with the diffident air was a phenomenal drummer. Everyone listened.

His precise blending of touch, taste, and an almost unbelievable technique were a joy to listen to. His technique was certainly as great (though differently applied) as that of Buddy Rich. And through it all, he played with a loose, easy feeling interspersed with subtle flashes of humor reminiscent of the late Sid Catlett.

That is the way Joe sounded then, and I will never forget it. Everyone knew that here was a discovery.

Word of his amazing ability spread like fire among the musicians, and soon he was inundated with offers of work. It was not long afterwards, following a short period with Stan Kenton's band and some dates with Johnny Smith's group, that Joe became a regular member of my group.

We opened at the Blue Note in Chicago in May 1953 and later returned to the Hickory House.

Every night it was the same thing: the place was crowded with drummers who had come to hear Joe.

He practiced unceasingly between sets, usually on a table top, with a folded napkin to deaden the sound and prevent the customers and the intermission pianist from getting annoyed. Sometimes the owner would walk over and say irascibly, "Stop that banging!"

But usually no one bothered him, and he gave his time generously to the drummers who came to talk with him. Soon he had some of them as pupils.

And wherever we played, it was the same. Young drummers appeared as if by magic, to listen to Joe and talk to him and to study. They arrived at all hours, in night clubs, at television studios, in hotels. We called them "the entourage." Several of them now are playing with top groups in various parts of the country.

During this period, Joe, bassist Bill Crow, and I started doing a lot of television, and recorded several LPs for Capitol. Nineteen-fifty-five was a good year for us. We received the Metronome small group award, and Joe won the Down Beat International Critics poll new star award. It was presented to him on the Steve Allen Show.

About that time, Joe and Bill were making so many freelance record dates that I told them I thought I should open an office and collect 10 per cent!

Some of Joe's best work was done on those sessions. At least, the best I have heard him play. There is a wonderful recording that he and Bill made with Victor Feldman and Hank Jones which, unfortunately, never has been released.

But there are other albums in which you can hear Joe at this period. One was an album done by Grand Award, with a group led by trombonist Bob Alexander. Chloe is easily the finest track. There's an interesting vocal and drum exchange with Jackie Cain and Roy Krai in a piece called Hook, Line and Snare in an album they did together. And he recorded some sides with my husband Jimmy and myself. This was more on the Dixieland kick, which points up Joe's extreme flexibility.

There are also some wonderful sides Joe made with Gil Melle, Sal Salvador, Sam Most, Lou Stein, John Mehegan, Tal Farlow, Helen Merrill (with Gil Evans' arrangements), and with Jimmy Raney and Phil Woods.

Alas, though for a time he turned down all offers, I was not to keep Joe with my group forever. And when I lost him as my drummer, my one consolation was that he was going to join a musician whom I respected very deeply: Dave Brubeck.

Joe joined the quartet in October 1956. Since then he has gone on growing.

Indeed, his playing has altered considerably, partly because of his fanatical desire for improvement and change, partly because the kind of playing Dave requires from a drummer is different from the techniques that Joe used with my group.

With me, Joe had concentrated more on speed, lightness of touch, and beautiful soft brush work. Dave, both a forceful personality and player, requires a background more in keeping with his far-reaching rhythmic expositions, and someone who can match him and even surpass him on out-of-time experimentation.

Today, Joe, though a complete individualist, hews closely to Dave's wishes as far as accompaniment is concerned. But he cannot help popping out with little drummistic comments, subtle or explosive, witty or snide — depending on his mood at the moment.

It is Dave's particular pleasure to go as far out as possible in his solos, and have the rhythm section carry him along. For this reason, the drummer must have a very highly developed sense of time and concentration to keep the tune moving nicely while these explorations are under way.

Bassist Gene Wright and Joe — "the section," as they refer to each other — do this most ably. Wright's admiration for Joe is unbounded.

"There's never been any tension at all from the day I joined the group," he said. "Joe makes my job very easy. We play together as one, and when a drummer and bass player think together, they can swing together. As a person, he's beautiful, and it comes out in his playing.

"There are no heights he cannot reach if he can always be himself and just play naturally. His potential is far beyond what people think he can do, and he'll achieve it some day."

Like any musician, Joe has detractors, those who can be heard muttering to the effect that he's a great technical drummer but doesn't really lay down a good beat — or, in more popular parlance, "He don't swing, man." But these detractors are remarkably few, and Brubeck is vehement in saying, "They're out of their minds!"

"Joe swings as much as anybody," Dave said, "and he has this tremendous rhythmic understanding. You should have heard him over in India with the drummers there. They just couldn't believe an American drummer could have that kind of mind, to grasp what they were doing. They said it would probably only take him a little while to absorb things it had taken them a lifetime to learn.

"As it is, Joe assimilates things quicker than any jazz musician I know, and he has the biggest ears. He was able to do many of the things the Indian drummers were doing, but they couldn't do what he does because they're just not technically equipped for it.

"How has his playing affected my group?

"I would say we have a better jazz group since Joe joined us. He really pushes you into a jazz feeling. And in his solos, when he gets inspired, he does fantastic things. Sometimes he gets so far out it's like someone walking on a high wire. Of course, he doesn't always make it, and then he'll say, "Oops!" But then he'll come right back and do it next time around. He is a genius on the drums."

Paul Desmond is just as forthright in his comments about Joe. "Joe can do anything anybody else can do, and he has his own individuality, too," Brubeck's altoist said. "Do we usually play well together? Yes, unless we're mad at each other! Naturally there are times, as in any group, when there might be a little difficulty of rapport if we are feeling bad. Playing incessantly, the way we do, night after night, it's almost impossible once in a while not to be bored with each other and with one's self. This is never true of Joe, especially on the fours."

I asked Paul how he felt about the rave notices that Joe has been getting since he joined the group.

"Well, Dave and I have been on the scene for about ten years now," he replied, "and it's only natural that somebody new, especially a drummer as good as Joe, would rate the attention of the critics. He definitely deserves all the praise he is getting. I think he's the world's best drummer, but it's his irrepressible good humor on and off the stand that I dig most of all."

Similar views were shared by a good many other persons, among them Joe's friend and long-time co-worker at the Hickory House, bassist Bill Crow, though he expresses it a little differently.

He always has amazingly precise control of his instrument at any volume, at any tempo, on any surface, live or dead. He's very sensitive to rhythmic and tonal subtleties and has a strong time sense around which he builds a very positive feeling for swing. Extraordinarily aware of the effect of touch on tone quality, he uses his ears and responds with imagination to the music he hears associates play.

With these assets, I nevertheless feel Joe isn't a finished jazz drummer, considering his potential. He can play any other kind of drum to perfection, but I don't think he's saying a quarter of what his talent and craftsmanship would inevitably produce if he were playing regularly with musicians who base their rhythmic conception on the blues tradition.

I know that Joe is attracted to this tradition, uses it as a focal point in his establishment of pulse, and feels happiest when he is playing with musicians who work out of this orientation. But he has never yet found a working situation where anyone else in the band knew more than he did about the subtleties of it . . .

He still has to find an environment that would demand response and growth on a deeper level. He needs to solve the problems presented by soloists like Ben Webster, Sonny Rollins, Harry Edison, or Al Cohn. He has to discover from his own experience how the innovations of Dave Tough, Sid Catlett, Kenny Clarke, or Max Roach can be applied to various musical situations. But primarily, he needs to play with Zoot Sims-type swingers who will reaffirm his feeling for loose, lively time.

Now that Joe's home base is San Francisco, he and his wife Ellie (they were married in 1954 while we were playing at the Hickory House) maintain an apartment in town. They have formed a close friendship with Ken and Joan Williams, owners of a San Francisco drum supply shop where Joe teaches every day he's not on the road and where he practices incessantly. The feeling his pupils have for him is nothing short of hero worship, and his opinions and views are digested word for word.

As Sam Ulano, a noted New York drum teacher puts it, "One of the great things Joe has done to influence the young drummers is to make them more practice conscious. He has encouraged them to see the challenge in practice and study, and I think it is important, too, that people should know how Joe has completely overcome the handicap of poor vision to the extent that few people are even aware of it. This disability has acted as a greater spur to him, already filled as he is with

deep determination to perfect his art, and others with similar problems can take note and gain hope and encouragement from it."

A conversation with Joe, no matter on what subject, invariably comes back to a discussion of music in one form or another. Musicians for whom he has veneration and respect range from veteran drummers Gene Krupa and Jo Jones to pianists Hank Jones, Bill Evans, and John Bunch. Phil Woods is one of his favorite horn players, and he admires Frank Sinatra, Peggy Lee, Anita O'Day, and Helen Merrill. His tastes in music run from plaintive gypsy violin music to the Brandenburg concertos.

Joe confesses to a dream for the future of having his own group. He would like to have his long-time friend, altoist Woods, in it.

But I'm not really ready for this yet. What I'd like to do right now is to develop greater facility, plus ideas, and improve my mind musically. To have basically good time—that's the first requisite, of course. Taste comes with experience. Then, too, you must have a good solid background to enable you to express yourself properly.

This is one of the things Mr. Stone did for me when I studied with him, and I owe him a great deal. He taught me how to use my hands. My idea of perfection would be good time, plus technique, plus musical ideas. Technique alone is a machine gun! But it sure brings the house down.

Years ago I was impressed by technique more than anything else. I think what made me go in for this so much when I was working with you, Marian, was that I was shocked by the lack of it in the New York drummers. I didn't realize at the time that a lot of them might be thinking more musically and developing along other lines. Now I listen for different things and I try to think of a musical form in my solos—a musical pattern. And when you know you're right, and it feels good to you— without sounding mystical or corny, sometimes things just come rolling out—building and building—a sort of expansion and contraction, you know? Now, take Buddy (Rich). If you want to use the term great, he's great. And Shelly (Manne)—I admire him very much and Louis Bellson, too.

Years ago Joe Raiche and I went to see Louis at Holyoke, and we invited him back to the house. I'd started experimenting with the finger system, but he really had it down, and as we sat at the kitchen table and talked, and he showed me some things. I sometimes think I played better in Springfield than I do now, though I've learned an awful lot from playing with Dave and Paul [Desmond], and Dave's such a good person to work for.

Being with this group is a marvelous experience for me. I'm grateful for the freedom Dave gives me, and he does give me plenty, both in concerts and on the albums. Working with him is interesting because he's very strong in what he believes in. But then so am I, and we both know this. So we respect each other's views, and we compromise—each of us gives a little. And as Dave said to you, we've found a point of mutual respect and understanding. We know we don't agree completely, and yet we can go on working together and enjoying it.

There's so much to be done — if you've got the mind and the imagination. That's what the drummer needs — the mind! And talent? You know what that is? It's 97% per cent work and 2 % per cent b.s.

I want to be as musical as I can — play the best I can for the group I'm with — and be myself. If I can do that, then I'll be happy.

Joe Morello: With A Light Touch

Marian McPartland

All in Good Time

“Joe Morello is a man of many natures. Restless, quiet, at times effervescent, at others the life of the party or completely aloof. Like the dark side of the moon, there is much about him that is unknown to most persons, perhaps even to himself. Yet he is also naive and funny. One moment, he will exclaim, with a schoolboy grin, "I feel like a sick sailor on the sea of life." Two minutes later, he will mutter moodily, "I should have been a monk." One could use a divining rod, sextant, sundial, geiger counter, and crystal ball to anticipate—and keep track of—the many verities of his nature.

To many young drummers, he is like a savior. Accordionist-organist-singer Joe Mooney calls him the well-dressed metronome. To his detractors he is merely a gifted drummer, an exceptional technician who can be hostile, even arrogant, at times. He has been called a prima donna, whose mood can change from animation to black despair without notice.

But people who know him well know, too, that he is also gentle, idealistic, and sensitive, a searcher for something he cannot name, who daydreams dreams, many of which already have come true.

"Do you know—I'm the only drummer who ever won the poll who doesn't have his own band?"

Morello says that with a big grin. Having made a clean sweep of most jazz popularity polls three years running — including Down Beat's Readers Poll—one would imagine he is delighted with the way things are going, especially since he has the salary and prestige of many a leader, with few of the responsibilities. Possibly the highest paid and certainly one of the most respected and admired drummers in the country, he can afford to smile.

"I've been lucky," he says. But anyone who knows Morello knows well that hours of practice, rigid discipline, and a continuing pursuit of perfection have had more to do with his current eminence than simple luck.

Further goals are pictured clearly in his mind's eye: "I can always see that straight line, and then I know I'm right."

Joe has been guided in this intuitive fashion many times, first perhaps when he decided to give up violin in favor of drums, overruling his father's original wish that he should become a painting contractor. Later, he decided to go to New York City ("I told my father I'd give myself six months to make good — if I didn't, I was going to go back to Springfield"). Later still, he joined my trio and while with it from 1953 to 1956 started to build the reputation he now enjoys. With growing confidence, he felt ready, in 1956, to join Dave Brubeck, with whose quartet he has established himself as a percussion virtuoso.

The publicity and acclaim he has received over the last nine years has been of inestimable value to him, for Joe, outstanding as he is, needs a showcase for his talents, and Dave has been more than generous. Dave has shared his spotlight with Joe and given him ample solo space. No leader could have been more considerate.

Though undoubtedly grateful, Joe has made full use of the spotlight, even to the extent of some artless scene-stealing— twirling the sticks, shooting his cuffs during a piano solo, delicate sleight of hand with the brushes, and other diversionary tactics.

However, Joe is probably the one drummer who has made it possible for Dave to do things with the group that he would have had difficulty accomplishing otherwise. Joe's technique, ideas, ability to play multiple rhythms and unusual time signatures, humor, and unflagging zest for playing is a combination of attributes few other drummers have. All these in addition to his ability to subjugate himself, when necessary, to Dave's wishes yet still maintain his own personality.

Joe is fascinating to watch play — he may have several rhythms going at one time, tossing them to and fro with the studied casualness of a juggler. Yet through it all, the inexorable beat of the bass drum (not loud—felt more than heard) holds everything together. He moves gracefully, with a minimum of fuss, but with a sparkling, diamond-sharp attack, reminiscent of the late Sid Catlett.

Sometimes a quick, impish grin comes over his face as he plays a humorous interpolation, and then he looks for all the world like a small boy throwing spitballs at his classmates. Though he seems withdrawn—remote at times—his movements are so expressive that when he breaks into a smile and glances around at Gene Wright, the group's bass player, one can sense his pleasure and can be a part of it.

Despite Joe's varying emotions and changing moods, there is one thing about him that never changes, except to grow stronger: his love of playing. This love is reflected in everything he does, his approach to life, to people, to himself.

As long as I have known Joe, he has had fine musical taste, technical control, and a light touch "delicate as a butterfly's wing," to quote Dave Garroway, and though he plays a great deal more forcefully with Brubeck than he did with my trio, still the lightness is there most of the time.

"Underplay if possible," he told me recently. "If you start off at full volume, you have nowhere to go. Be considerate of the other members of the group — drums can be obnoxious or they can be great."

Where Joe is concerned, it is invariably the latter. I have never heard him play badly.

Now that he is, in the eyes of many, the No. 1 drummer in the country, he could be the man to change the course of current drumming. In this era, when sheer volume appears to be the criterion for percussion excellence, when the artisan has apparently been replaced by the unschooled, Joe Morello stands out as something of a phenomenon. He is not an innovator, but he draws from the styles of drummers past and present whom he has observed and admired to produce a sound, a touch, a feeling that is essentially his own.

He has been criticized rather than praised by some of his peers, who tend to enjoy a barrage of sound, crudely produced, rather than the finesse, delicacy, and range of dynamics that Joe draws from drums. Nevertheless, it may be that he is, in the words of drum manufacturer Bill Ludwig, "an apostle — someone who can preach the word to all the kids coming up, show them how to play the drums properly, how to play cleanly, to direct their studies and their talents to the most musical approach to the drums possible."

In the last few years, he has had opportunity to talk with novice and would-be drummers and to show them some of his ideas.

They crowd around him after concerts. They dog his footsteps in hotels. They gather in dining rooms and coffee shops. Joe also gets three months a year off from the Brubeck group and travels the country to appear at drum clinics in schools, music stores, and auditoriums for the benefit of the local drummers, students, and teachers.

The clinic idea is not new, but Joe has brought a different dimension to it. From being a comparatively small operation, in which possibly a hundred persons would come to see a name drummer play a solo and perhaps give a short talk, clinics are now getting to be big business. When Joe appears at one, the hall is invariably jammed; if the room holds five hundred, another two hundred are turned away. Last year Joe pioneered the clinic idea in several European countries— England, Holland, Germany, and Denmark. More recently he has brought drum clinics to Puerto Rico. This year, he will give clinics in new territory—when the Brubeck quartet goes to Australia, New Zealand, and Japan.

Everyone associated with the clinics is happy. "For every one that he does, I could book ten," said Dick Schory of the Ludwig Drum Company, Morello's sponsor. "There has never been a drummer who can draw people like he does, and he can keep them on the edge of their seats for two hours. He's a very good extemporaneous speaker, and he's such a ham that I'm sure he'd rather do this than play the drums. He razzles and dazzles them with his playing, and he has this fantastic sense of humor — it's not dry-as-dust lecturing — he makes it interesting, and he believes in it."

He will relax the crowd at the start of the clinic by kiddingly referring to it as a "hospital for sick drummers—and I'm the sickest of them all." Or "I guess all you people must need help or you wouldn't be here." Last year in London, at the first clinic there, he greeted deafening applause with, "If I'm elected, I promise ... ." After a particularly sizzling display, which had everybody on his feet applauding, he shook his head morosely and muttered, "I must be getting old."

Joe usually divides the two-hour lecture into several parts— first describing his drum setup, what size the drums are and why he uses them. Once in a while, he will do impressions of well-known drummers with devilish accuracy. Sometimes he plays a short but hilarious solo, doing everything wrong, to expose areas in which a drummer could improve. He answers questions tirelessly and takes great pains to make sure that everyone has understood his meaning, going over a point several times if necessary.

I’d like to have him do these clinics all the time," Bill Ludwig said. "He's a natural teacher, and he's at his best with kids. Nothing is too much trouble — he loses himself in it. This is the answer to the uneducated drummers of today— show them what real study is.

"As far as actual talent is concerned, there hasn't been anyone quite like him — no one who has this devotion to the instrument. And he's such a gentleman.

"He has brought realism to the clinics; he's not just a performer who will pass the two hours giving a technical demonstration. This guy opens his heart and says, 'Here it is, use it, free.' I've seen clinicians who would spend two hours showing off their dexterity, but Joe does things that are useful to the students."

One can only guess at Joe's feelings about this acclaim. It surely has not changed his attitude toward his work. He has never let up. When at home, it's still practice, practice. He seems to derive comfort from this, almost as if the drums were a refuge where he feels secure and can gain reassurance.

The standing ovations, the adulation of laymen and musicians alike, contribute to his well-being. But his real satisfaction comes from the clinics. With every patient explanation of a point to a student, he gives something of himself, and the effects of it are more gratifying than the concert applause. He gives the best that is in him with a forthright and unequivocal stance.

Many people in music believe that Morello's major contribution to music is yet to come — certainly as a teacher and perhaps with his own group. Many possibilities are open to him. Currently, few musicians think of him solely as a jazz drummer; most look upon him as a drum artist, because much feeling still exists that he is not really a hard swinger. This may be a carping criticism, but it appears that his work with Brubeck seems to call for just about every kind of playing but "hard swinging." There are some good grooves, but the constantly changing, fluctuating rhythms of 5/4, 9/8, and so on (as well as those Dave imposes on the rhythm section in his solos) impede any steady swinging.

When Joe goes "moonlighting" and sits in with different groups (he recently played a set with Dizzy Gillespie and gassed everybody), he is almost like a racehorse that has been allowed to run free after being reined in; and on these occasions, he proves again that he can swing strongly when he is among hard cookers. Then his playing takes on a different quality. It becomes more uninhibited, more relaxed.

A chat with Joe, no matter how it starts, almost invariably ends as a discussion of music in one form or another. Sometimes he gets so wound up that it's more like a filibuster. Never one to hold back, he will animatedly discuss the modern drummer:

Those things they are playing today . . . Max Roach did that beautifully years ago

— Roy Haynes, too (in fact when Bob Carter and I were with you, Marian, we did that same thing—sort of conservatively). But when I see a guy take the butt end of the sticks . . . when I have to guess where the time is, I could cry. Who's going to play against that? Funny—some sixteen-year-olds are digging it! When I was sixteen, I listened to Krupa, Buddy Rich, Max [Roach], Jo Jones.

This whole thing apart, any drummer should be able to play time. These kids coming up ... they have a choice. Some of them may blow it, but some of them are going to come along and make everybody look like punks.

You know, Marian, you used to say my playing was too precise, but I really think I'm beginning to play more sloppy now. But I'm continually trying to get myself together and play something different, and one thing Dave has taught me — that's to try to create. I admire him harmonically, and you just can't dispute the fact that he plays with imagination. Oh, he's not always the easiest guy to play with, but he's so inventive. . . .

Years ago, I wanted to play like Max, but then I found out you've got to develop your own style . . .good or bad, it's me. But I can't play well all the time — I'm not that consistent. Like, I don't expect to be happy all the time either ... everyone's been disappointed. But since I've been with Dave, I've had a lot of acclaim, and I'm very grateful for it. Some manifestations of that acclaim have been like dreams come true—you've never dreamed the dreams I've dreamed and had them come true! If I never do more than I have done already, I'm proud and happy for what I've accomplished — God has been good to me.”